Dams, hydro-electric projects: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

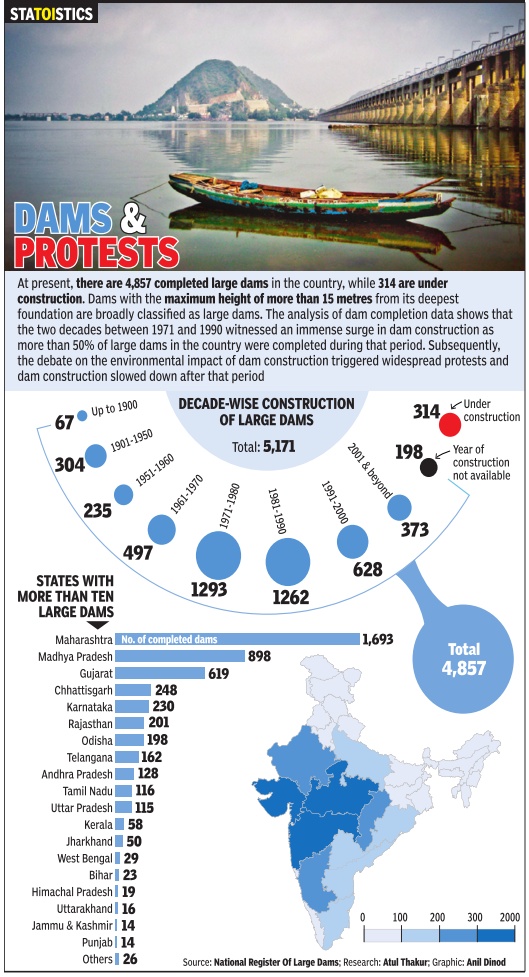

Construction, 1900-2014

See graphic:

Decade-wise construction of large dams (Hydro-electric projects): 1900-2014, and their statewise distribution

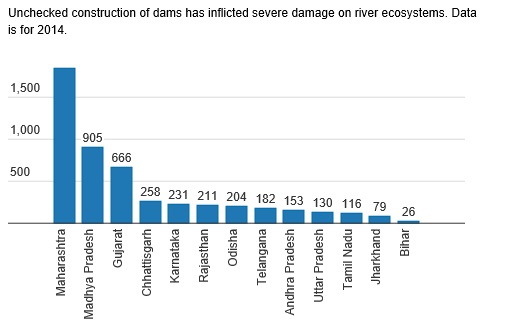

Unchecked construction of dams in India, as in 2014

Ageing and safety issues

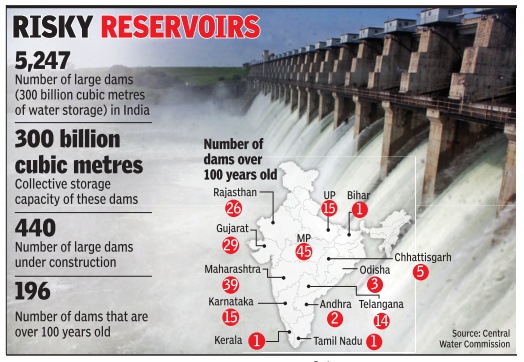

`Break analysis' of 5,247 large dams: 2017

196 Of Them Are Over 100 Years Old

For the first time, the Centre is planning to conduct a `break analysis' of 5,247 large dams across the country , and put in place an emergency action plan, especially for the 196 that are over 100 years old. Of these 196 dams, 72 are in the southern states and Maharashtra.

Break analysis is the examination of dams to identify potential failures that may result in an uncontrolled release of water. It involves the characterisation of threats to public safety that a dam poses.

The government has already drafted a `dam safety bill', currently being reworked by the Niti Aayog.

There are two safety issues: the risk of breach and floods, and the decreasing ability to hold as much water as the original capacity (which means less live storage and per capita availability of water). These concerns make maintenance more critical for dams, though not all are in a dilapidated condition or in need of immediate repair.

In October 1987, the Centre had constituted the National Committee on Dam Safety (NCDS), which was tasked with overseeing dam safety and suggesting improvements. The committee, headed by the Central Water Commission chairman, met 37 times and has been instrumental in the maintenance of dams.

Dam expert Captain S Raja Rao, who was secretary of the Karnataka water resources department, said: “The safety aspect, especially with dams in flood-prone areas, is critical. Take the Alamatti dam (in Karnataka), and you'll see its size was increased based on advice from the World Bank, but it has several drawbacks.“

However, he pointed out that successive governments had been spending a lot of time and money on dam upkeep.“There is a continuous effort to improve the inspection galleries in dams (which are key indicators of a dam's health) and a project called DRIP (Dam Rehabilitation and Improvement Programme) is under way ,“ Rao said.

DRIP , which was started under the UPA government in April 2012 and has been working with five state governments (Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh and Odisha) and two agencies (Damodar Valley Corporation in Jharkhand and Uttarakhand Jal Vidyut Nigam Ltd), was conceived with an estimated budget of Rs 2,100 crore.The project cost has now been revised to around Rs 3,400 crore and the World Bank has agreed to fund 80% of that, DRIP director Pramod Narayan told TOI.

“While the goal is to eventually work on all dams in the country , we are working on 225 dams, and these don't include all the 196 dams that are more than 100 years old. For the first time, last month, we prepared a draft emergency action plan, which deals with situations that (could) arise in case of a breach, areas affected, rehabilitation, and so on,“ Narayan said.

One big problem, Rao said, was the fact that the majority of India's large dams had dysfunctional scouring-sluices (which are responsible to keep silt out of the dams), affecting storage capacity and posing a threat to the structure.

The Tungabhadra dam in Karnataka is just 64 years old, and more than 37% of it is filled with silt. In June, the government conceded on the floor of the state assembly that it is impossible to remove more than 0.11% of the silt. “Older dams have a larger problem of silt,“ Rao said, while Narayan added that continuous monitoring and regular intervention alone can prevent this problem from worsening.

As in 2023

Vishwa Mohan, April 3, 2023: The Times of India

From: Vishwa Mohan, April 3, 2023: The Times of India

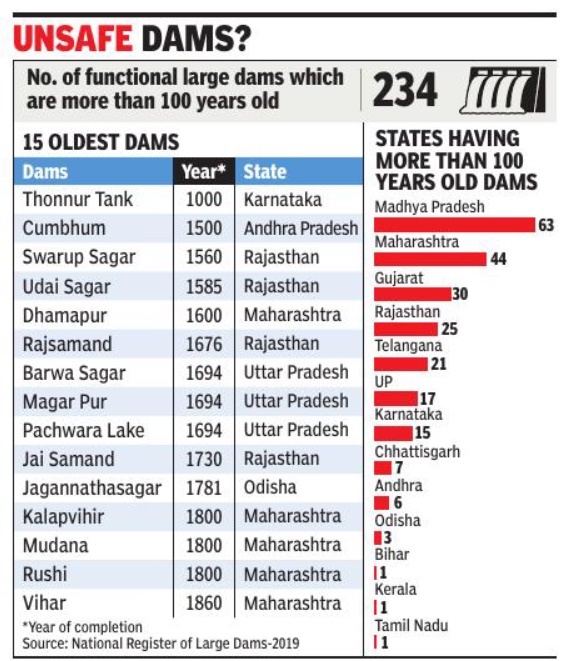

New Delhi : Aparliamentary panel has expressed concerns over the safety of aging dams in the country, saying there are 234 functional large dams in India which are more than 100 years old — some of them over 300 years old — but so far none of these dams have been decommissioned.

Dam decommissioning is avery long process which includes removal of hydro-electric generation facilities and recontouring of river channels through ecologically viable interventions in the catchment areas. Since dams have a life span, few countries, including the US, have decommissioned their dams and restored the natural flow of rivers.

Though the dams are normally designed for 100 years of useful age and their functional life also gets decreased with progressive reservoir sedimentation concurrently reducing project benefits, none of the dams have, so far, been decommissioned in India.

The parliamentary panel —standing committee on water that submitted its report to Parliament on March 20 — recommended the Jal Shakti ministry take suitable measures for evolving a “viable mechanism to assess the lives and operations of the dams” and also persuade the states to decommission those which have outlived their lifespan.

Dam safety has always been an issue in the countrywhich in the past reported as many as 36 dam disasters which include the worst one in Gujarat (Machu dam in Morbi) where around 2,000 people died and over 12,000 houses were destroyed in 1979.

The panel was informed by the ministry that “there is no mechanism to assess the viable lifespan and performance of dams”. Regular maintenance of dams is, however, undertaken for their health assessment and safety. The dams are mostly owned by state governments/public sector undertakings (PSUs)/ private agencies which carryout the operation and maintenance (O&M) works of the dams in their jurisdiction.

The Centre legislated the Dam Safety Act in 2021 to provide for surveillance, inspection, O&M of a specified dam.

The panel also noted challenges in water sector and pitched for a need to adopt multipronged strategy such as “strengthening of legal and institutional framework” for water conservation, crop diversification, growing of crops requiring less water, revival of dry springs, floodwater harvesting and ensuring better percolation of rainwater.

Bhakra-Nangal Dam

Asit Jolly , Water walls “India Today” 21/8/2017

Among India's earliest river valley development projects, the Bhakra-Nangal multi-purpose dams were crucial to the success of the Green Revolution in the northern states of Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan. Water from the dams brought irrigation to 135 lakh acres in the three states, besides preventing floods. At Independence, close to 80 per cent of the cultivable, canal-irrigated area of erstwhile Punjab fell in West Punjab and consequently went to Pakistan. This left the eastern or Indian portion of Punjab with scanty irrigation resources. Although envisaged even before Independence, preliminary earthwork on the Bhakra dam only started in 1948. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru inaugurated the construction on November 18, 1955, pouring the first pail of concrete into what was to be the firm foundation of the dam. He called it a symbol of "nation's will to march forward with strength, determination and courage", despite the "great shock" and "grievous wound" suffered by Punjab. On completion, the Bhakra-a concrete gravity dam-was one of the highest in the world at 741 feet, just three feet short of the US's then tallest Hoover dam. At its inauguration on October 22, 1963, Nehru said, "Call it a temple, a gurdwara or a mosque, it inspires our administration and reverence." Other stages of the project, including a downstream dam at Nangal, were completed by the early 1970s. Back then, the Bhakra-Nangal project was the only one in Asia capable of achieving generation capacities of 1,500 megawatts.

Today, the dams are part of the Bhakra Beas Management Board (BBMB), which is critical to the operation of the northern electricity grid. The BBMB powerhouse, including Bhakra-Nangal, generates between 1,900 MW and 2,800 MW in the summer months, and 500 MW to 1,900 MW in winters. The hydroelectric projects allow for thermal power stations in the region to operate at base levels. The Bhakra-Nangal and Beas projects, which annually supply 28 million acre feet (MAF) of water, have hugely contributed to the continuing success of the Green Revolution as well as the massive increase in milk production in the northern states.

Hydro-electric projects

Nivedita Khandekar, February 9, 2021: The Times of India

From: Nivedita Khandekar, February 9, 2021: The Times of India

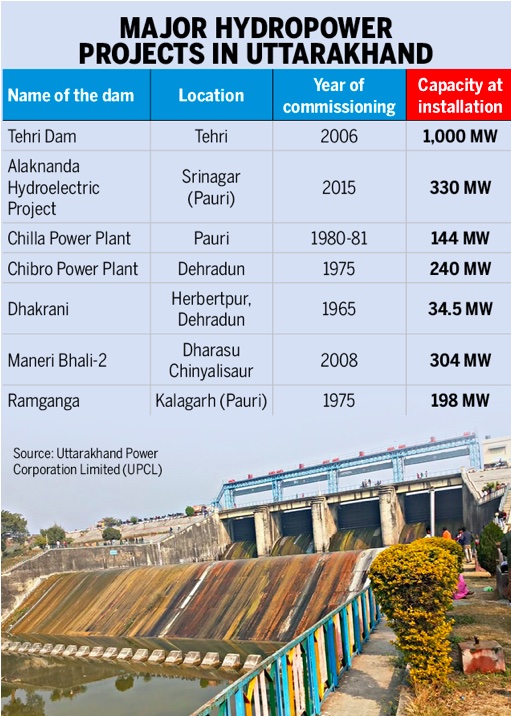

See graphic:

Major Hydropower projects in Uttarakhand

“Many Hydro-electric projects (HEPs) have been sanctioned in side protected areas, two inside the core zone of the NandaDevi National Park. Two projects have been sanctioned on the Mandakini river inside the Kedarnath Musk Deer Sanctuary and another is located just at its boundary. Earlier, four projects on the Gori Ganga were inside the Askot Musk Deer Sanctuary. Another six large projects on the Dhauliganga (E) and Kali rivers were also within the Askot Sanctuary. Efforts made by the developers to have large parts of the sanctuary developers to have large parts of the sanctuary de-notified finally succeeded with the Supreme Court ordering a fresh demarcation of the sanctuary. Now most of the above projects are outside the Sanctuary.”

Ganga

No new hydel units on Ganga/ govt 2019

Vishwa Mohan, February 9, 2021: The Times of India

Even as dams are being discussed afresh after the glacier disaster in Uttarakhand, the Centre had taken a decision during PM Narendra Modi’s first term itself not to take up any new hydro-electric project on river Ganga and its tributaries in the state.

The decision, taken by the Prime Minister’s Office, will continue to be the guiding force for any future projects in the region which saw a devastating glacial burst on Sunday that affected Dhauli Ganga, Rishi Ganga and Alaknanda rivers. “All projects in which the work has not started on the ground shall be dropped,” said the written ‘record of discussion’ and decisions taken during the meeting, chaired by the then principal secretary to the PM, Nripendra Misra, in February 2019. “These decisions still stand. Our position has not changed. We’ll not take up any new project,” Environment Secretary R P Gupta told TOI.

Sources said the PM had intervened during a discussion and remarked that ways could be found to support the power needs of the state rather than building new dams in the eco-sensitive region.

The written record of the 2019 meeting at PMO, accessed by TOI on Monday, shows that senior officials, had during the deliberations decided that only seven projects, which were reported to be more than 50% complete, would be taken up for construction. Considering the “revenue and opportunity” loss to Uttarakhand in view of dropping off the state’s three projects, it was decided that the state would be compensated for the projects on which the work has already started.

Uttarakhand

Vishwa Mohan, February 9, 2021: The Times of India

U’khand has over 40 hydel projects

The flash flood that claimed several lives in Chamoli on Sunday has brought the hydropower plant projects of Uttarakhand under the lens. Experts believe that the over-exploitation of rivers in the fragile Himalayan ecosystem is leading to several catastrophes, reports Shivani Azad. At present, several hydel projects — with a cumulative capacity of around 2594.85 MW — are operational in Uttarakhand. The rivers and basins in the state are dotted with 43 micro hydel projects. Between 2005-10, the state gave nod to over a dozen projects.

See also

Dams, hydro-electric projects: India