Darwesh

This article is an extract from

THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be duly acknowledged.

Contents |

Darwesh

The foundation of the various Darwesh orders is referred to the early days after Muhammad, and, if tradition is to be believed, earnest men united by a common tie, and worshipping God according to certain formulae, were countenanced by Abu Bakr and 'Ali. Before the birth of Muhammad, however, the mystical doctrines of the Cufis, tinged by the philosophy of the Hindus, penetrated the religious ranks of the East, and inspired Uwais Karani, in the thirty-seventh year of the Hijra (A.D. 657), to withdraw from the world, and found the first fraternity of mendicants. Imitating his example Abu Bakr and 'Ali organised two similar orders, and entrusted their management to Khalifas, or successors. From these congregations have sprang all the Darwesh orders of the present day; the Bistamis, Naqahbandis, and Biktashis being offshoots from the parent society of Abu Bakr, and the remaining houses from that of 'Ali. Hammer fixes the number of Darwesh orders at thirty-six, and mentions that only twelve existed before the foundation of the Ottoman Einpire in 1298, while the rest were established between the beginning of the fourteenth and the middle of the eighteenth century.

In Southern India Faqirs belong to one or other of fourteen households (Khanawadas); but several of the largest, and most popular, orders of Persia and Turkey are unrepresented. In Hindustan, however, various lists are given. Wilson in his Glossary enumerates ten classes:�

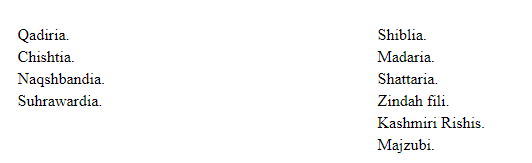

Mr. Blochmann, again, divides the Indian Darwesh orders into four greater and six inferior, as follows:�

In Eastern Bengal, however, only representatives of the Qadiria, Chishtia, Rafafi Madaria, and Naqshbandia are met with; while of late years no Sohagia has appeared.

The ordinary distinction between one class of Faqir and another is popularly made to depend on the observance, or otherwise, of the Shara', or precepts of the Muhammadan religion. The Ba-Shara', or Salik, by far the most respected, regulate their lives in accordance with the rules of Muhammadanism, while the Be-Shara', or Majzub, follow their own appetites and passions, eating and drinking whatever they fancy, and leading disreputable and scandalous lives. Many of them are poor demented creatures, like the Abdals of Syria, who wander about nearly naked, justifying their indecency by the text of the Koran, "the clothing of piety is better than apparel and fine garments."

The Salik are usually married men of settled habits; the Majzub are homeless beggars, who wander all over India dependent on the charity of the benevolent, and universally credited with supernatural powers. The former initiate disciples (murid); the latter rarely do so.

The Darwesh orders resemble in many obvious respects the fraternities of the Roman Catholic Church, the main difference between them and the rest of the people consisting in a strict observance of certain religions rites peculiar to themselves, and not in any cardinal diversity of belief. Tacawwuf, or the mysticism of the Cufis, does not embody any philosophical or religions system, but is identical with the rule of a monastic order. Each Darwesh society has a rule of its own, comprising some simple, and many obscure, formulae; while all acknowledge Muhammad as the prophet, and the Koran as the handwriting of God.

Contrary to the opinion of the 'Ullama, Darweshes believe that many texts of the Koran have a mystical as well as an obvious meaning, and maintain that the distinctive tenets of the various orders are based on texts only understood by a privileged few.

The Hadis, or traditionary precepts of Muhammad, and the commentaries of the four great Doctors, are also admitted to be unerring, and binding on all believers. The peculiar religious doctrines of Cufis are still hidden from us, and the minute shades of difference separating one from the other have not been determined. Darweshes, however, concur in believing that God is the only object of contemplation, and that the highest truths can only be mastered by rapturous abstraction, or by falling into a trance, when the outer world of perception passes away and the soul enters into the unseen and spiritual world.

The Eastern mystics derived many of their peculiar conceptions from the Greek Plotinus, the Egyptian Aristotle, as they call him, who asserted that being and knowledge were identical Cufis, therefore, maintain that to know the Divine Intelligence it is necessary to become that Divine Intelligence; and as the soul is an emanation from God, a ray of His ineffable brightness, it must lose its personality, becoming absorbed, during the ecstatic state, into the Divine Essence. The Spanish Quietists asserted that the soul became purified, and prepared for reabsorption, by prolonged austerity; but the Cufis regard the soul as the slave of the will, being at pleasure constrained to unite with the Great Spirit. By constant meditation, therefore, on the attributes and beneficence of God, and by renunciation of the world and its temptations, the Darwesh acquires Ma'rifat, or knowledge of Him.

It is the privilege of only a very few to gain this knowledge, but, through the mercy of God, holy men have from time to time appeared to guide mankind towards salvation by pointing out the path (Tariq) leading to perfect knowledge. Each messenger has indicated a new route; but all tend towards the same goal. According to some authorities there are always forty saints (Chhihal tanan) with one chief, or Qutb, living, round whom the whole Muhammadan world revolves. Several of these Qutbs have established orders; but others have merely revived and reformed those already existing.

(a) Chishtia

The founder of this Indian Darwesh order, Khwajah Mu'inuddin, son of Ghiyasuddin, a Sayyid of the house of Husain, was born at Chisht, a village of Sistan, in A.H. 537 (1142). When fifteen years old his father died, but his education was directed by Ibrahim Kandozi, a celebrated doctor, by Khwajah 'Usman, and finally by the great 'Abd-ul-Qadir Gilani. According to the author of the Qanoon-i-Islam, it was a certain Shaikh Abu Ishaq Chishti who organised the fraternity; but it is generally admitted that Mu'inuddin followed Shahabuddin Ghori in his invasion of India, A.D. 1193, and settled at Ajmir in a ruined temple sacred to Mahadeo.

It is popularly believed that the saint was in the daily habit of filling a water-skin (mashk) and hanging it on a bough. The water drops fell upon a "lingam" hidden beneath leaves and rubbish, and this, although quite accidental, so pleased Mahadeo that he conferred on the saint many miraculous powers. Hence it is that Hindus, as well as Muhammadans, make votive offerings at his tomb, especially in the month of October. Mu'inuddin died on Saturday, the 6th of Rajab, A.H. 636 (1238), and ever since Ajmir has been known as Dar-ul-Khair, the abode of goodness.

The Ajmir shrine has always been greatly favoured by the Muhammadan rulers of India, and Mu'inuddin became the patron saint of the Mughal dynasty. In 1544 it was visited by Sher Shah. In 1570, five months after the birth of Jahangir, Akbar walked to Ajmir on foot from Agra, a distance of two hundred miles, in fulfilment of a vow.

In 1613, Jahangir caused a brass kettle to be made at the shrine for cooking food for five thousand pilgrims. In 1614, he attributed his recovery from a violent fever to the intercession of the saint, and, as a token of gratitude and humility, had his ears bored. In 1616, when at Ajmir, he enclosed the tomb with a gold railing of pierced work, costing 1,12,000 rupees. In 1628, Shah Jahan, on his way to Agra, prostrated himself before it. In the wars which followed on the death of Aurangzib, the shrine was pillaged and destroyed, but Madhaji and Daulat Rao Scindiah erected the present plain building over the tomb.

The next celebrated member of this order was Makhdum Sayyid Muhammad Banda-nawaz, Gesu-daraz, or the long-haired, who resided at the courts of Firuz and Ahmad I, of the Bahmani dynasty, towards the end of the fourteenth, and beginning of the fifteenth centuries. His tomb is at Gulbarga in the Dakhin, and his 'Urs is held on the 16th of the month Zi-qa'da.

Before the reign of Akbar, Shaikh Musa, a descendant of Shaikh Farid-i-Shakarganj, resided at Sikri, where his wife bore several sons, the second being Shaikh Salim Chishti, whose life is so intimately connected with that of Akbar's family. The date of his birth is not given, but he was at the of his fame about 1569, when he foretold the birth of Prince Salim, the future Jahangir.

The Shaikh was married, and of several sons distinguished as soldiers, the most famous was Shaikh Ahmad, who became a Mancubdar of five hundred at the court of Akbar.1 Shaikh Salfm died A.H. 979 (1571), and was buried at Fathpur Sikri in a tomb which has been described "as a perfect gem of art, elaborately executed in white marble of the purest hue, and the most delicate sculpture."2 At the present day it is resorted to by thousands; and barren women, both Hindus and Muhammadans, tie pieces of string on the marble lattice work, in confident hope that they will conceive through the intercession of the saint.

Other followers of this order have earned lasting renown. At Agra is the tomb of Shaikh Ishmail Chishti Akbarabadi, who died A.D. 1655, leaving a great name for sanctity. Sayyid Shah Zuhur, who built a small earthen monastery at Allahabad, which still exists, is also renowned for the miraculous cures effected during his lifetime, and vows paid at his tomb are rewarded at the present day by restoration to health.

A few members of this Darwesh order are always to be found in Eastern Bengal, and one of them has resided for many years in the tomb of Shah Jalal Dakhini at Dacca; but the head of the fraternity, known as Sar-guroh, or Sajjada-nishin, always resides at Ajmir.

The Chishtia Faqirs, generally Shias, are very illiterate, and unable to read Arabic or Persian.

As a rule they are married men, who freely indulge in opium eating, but do not use Bhang, or other intoxicating drugs. Like many religious mendicants, Hindu and Muhammadan, they carry a large sea cocoa-nut (Lodoicea Sechellarum), called a Kishti, into which they receive alms of food and money.

Around the neck are hung three necklaces of glass beads known as Kantha, Zanar, and Tasbih, the last the rosary, consisting of a hundred and one beads. It is incumbent on each Faqir to recite the confession of faith (Kalma) five times daily for each bead, and during the first watch of the night ('isha-namaz), he must spend several hours in repeating texts of the Koran, and in counting his beads. On the right arm an amulet is bound, within which is contained a slip of paper on which is written the Sura Ya Sin,1 or heart of the Koran, as Muhammad called it.

Music, either instrumental or vocal, forms an essential part of their religious services, it having been observed by Mu'inuddin that singing was the food and support of the soul. When in a state of abstraction, or, animated by religious fervour, the Chishtia Faqirs break forth into loud and excited singing, and throw themselves into strange attitudes, hanging by their feet from trees, or arching their bodies backwards till the head touches the ground, and mistaking, as Gibbon has it, "the giddiness of the head for the illumination of the spirit."

These Faqirs eat and drink in any respectable house, and partake as readily of food cooked by a Hindu, or Christian, as by a Muhammadan.

(b) Qadiria

Throughout the Muhammadan world, from the shores of the Atlantic to the confines of China, the great Darwesh 'Abd-ul-Qadir Gilani is venerated as the first of spiritual teachers, and invoked in all seasons of danger, or tribulation. The following are a few among many titles indicating his superiority over all other saints, Piran-i-Pir, Pir-i-dastgir, Ghaus-ul-'Azim, and Ghaus-ul-Camadani.

Sayyid 'Abd-ul-Qadir was born in Gilan, a province of Iran, in A.H. 471 (1078), and while still an infant, by refusing to taste milk during the fast of Ramazan, he foretold his sacred mission. When seventeen years of age he went to Baghdad, and in A.H. 521 (1127) began public lectures. He was appointed guardian of the tomb of the Iman 'Azam abu Hanifah, who died in prison A.H. 150 (767).

The date of his death is uncertain, but most authorities fix it in A.H. 561 (1165). His body was interred in a suburb of the city, and around it so many saints have been entombed that Baghdad has acquired the name of Burj-al-auliya, or citadel of saints. The tomb of 'Abd-ul-Qadir is one of the most handsome buildings in modern Baghdad, being surmounted by a lofty dome, and enclosed in a garden watered by means of an aqueduct leading from the Tigris. The court is divided into a vast number of small cells, tenanted by Faqirs,

1 So named from the thirty-sixth Sura, which begins with these two letters. This chapter is so highly valued, that Muhammadana learn it by heart, and have it read to dying persons when in articulo.

1 For further particulars of the family, see Blochmann's "Ain-i-Akbari.

2 Roberts (E.) "Hindostan," ii, 5.

and the shrine is so richly endowed that about three hundred mendicants are fed daily.1 The inhabitants of Baghdad regard 'Abd-ul-Qadir as their patron saint, and call upon him on all occasions of peril, or affliction, by land or water.

Qadiria Faqirs are met with in all parts of the East, and in Egypt often earn a livelihood as fishermen. Their banners and turbans are properly white, but in India their dress is either green or white, while many prefer the red ochre dye, distinctive of Hindu Bairagis, for staining their coarse sleeveless tunic, known as "Azad-be-nawa." In Bengal Qadiria Faqirs are always married, their sons being initiated as soon as they come of age. The Urs, or annual festival, of the saint, is observed on the eleventh Rabia-us-sani.

The rites attending the admission of a disciple are symbolical of those observed after the death of a Muhammadan. The pupil being stripped and shaved, seven jars of water are poured over him, and as each jar is emptied the Kalma, or confession of faith, is repeated four times. A Kafan, or "Allah Nabi ka dalq," the peculiar dress of mendicants, and a red, black, or blue collar (gireban) of a singular pattern are put on him. A real Qadiria is recognised by this collar, which is worked by the Faqirs themselves, and composed of a certain number of stitches sewn in squares, never in curves. Should the stitches be too few, or too many, the impostor is unmasked, and is liable to have it snatched away by the true Faqir.

The novice finally receives a necklace (kantha) as well as a rosary (tasbih), and in return is expected, but not obliged, to pay a fee varying from four to ten rupees.

Qadiria Faqirs accept money and uncooked food from Hindus, and eat with most classes of Muhammadans, although they despise and ill-treat the Bediya and other Muhammadans of doubtful orthodoxy.

They never sell amulets to ward off disease, as other mendicants do, nor claim the possession of power to exorcise spirits; yet the public credit them as well as all religious mendicants with this faculty.

The wives of the Bengal Qadiria never join their husbands in perambulating the city, but, attending to their household duties, earn a little by embroidering muslins.

(c) Naqshbandi

This is one of the most widely dispersed, and most respectable, of Indian Darwesh orders. Followers of this "path" are very common in Hindustan, while in Bukhara and Central Asia they are so numerous that all pilgrims to Mecca from these distant countries are known by the Arabs as Naqshbandi.

The original founder of this religious order was one Ubaidullah, but Bahauddin by his writings defined the principles of the sect, and established it on a secure basis. Pir Muhammad Bahauddin Naqshband, a contemporary of Timour, died A.H. 791 (1388).1 He is the patron saint of Bukhara, and when Vambery arrived in that city, the inhabitants at once concluded that his long and perilous journey was only taken for the purpose of visiting the tomb of the saint. The shrine of Bahaud-din stands a few miles out of Bukhara, on the Samarkand road, the tomb being in a small garden, exposed to the weather, as every roof built over it has been thrown down by supernatural agency.

On one side is a mosque, in front of which is the famous Sang-i-murad, or stone of desire, worn and polished by the foreheads of generations of devotees, and adjoining is a large college. Over the tomb hang several rams' horns, a banner, and a broom formerly used in sweeping the sanctuary at Mecca.2 Pilgrimages are made to this shrine from the most distant parts of the Muhammadan world, and it is customary for each Bukhariot to visit it every week, three pilgrimages being looked upon as equivalent to one paid to the distant Ka'ba. The inhabitants think that by merely uttering "Bahauddin bala-gardan!" "Bahauddin, thou averter of evil!" they will be saved from all misfortunes.

According to D'Herbelot, Bahauddin wrote a work called "Maqamat," or discourses on various subjects connected with eloquence and academic studies, which is the guide book of the sect. The title of Naqshband was bestowed on Bahauddin because he "drew incomparable pictures (naqsh-bandi) of the Divine science, and painted figures of the Eternal Invention, which are not imperceptible."

In Bengal, the Naqshbandi Faqirs, usually called "Mushkil-Asan," a designation implying power to avert evil, are generally married men, and Ba-shara. On Thursday evenings they perambulate the streets carrying a lighted lamp (Shama'), and proclaiming that there is only One who can alleviate sorrow, and whose ear is always open to the cry of the penitent. They never ask for alms, but accept whatever is given and in return imprint a "tilak," or mark, on the forehead of the alms giver.

There are two ceremonies observed by Muhammadan women closely connected with the peculiar doctrines of this fraternity. The first is a fast called Muskil-Asan, observed on each Thursday in November. What its original signification was is now difficult to ascertain, but it was probably kept in seasons of adversity as at present, when after fasting for a day the celebrants eat Halwah, and another sweatmeat called Chitwah.

The other, known as Mushkil-Kusha," or dispeller of difficulties, is celebrated on the seventh, seventeenth, and twenty-seventh of the moon in each month, when a goglet-(Kuza), and a salt-cellar, are arranged for the service, after which the fast is broken by eating millet and the sweetmeats Jalebi and Nukal.

1 D'Ohsson places his death in A.H. 719 (1319).

2 "Travels into Bukhara," by Sir A. Burnes, ii, 271. "Travels in Central Asia," by Arminius Vambery, 194.

1 "Geographical Memoir of the Persian Empire," by J. M. Kinneir, p. 250.

(d) Rafia

The Rafa'i, or Gurzmar, Faqirs are less frequently met with in Bengal than any of the other Darwesh orders; but occasionally they wander into Eastern Bengal seeking disciples and soliciting alms.

The founder of this fraternity was Sayyid Ahmad ibn Abual Hasan al Rafa'i, called Al Kabir and Al Wali al 'Arif. He was nephew (bhanja) of 'Abdul Qadir Gilani, and descendant of an Arab called Rifa'a. His .abode was in the Bata'ih, or marshes, forming the delta of the Euphrates, and he died in the village of Om 'Obaidah A.H. 578 {1182), aged over seventy.1 Leaving no issue, the family of his brother succeeded, and still preside over the order. Tradition has preserved a favourite saying of this haughty saint, "This foot of mine is over the necks of all the saints of Allah;" but is silent regarding his life.

The Rafa'i Faqirs are the same as the Howling Darweshes of Constantinople, who, although rare in India, are very numerous and popular in Turkey and Egypt.

Like the priests of Baal, the Rafi'i practise the most astonishing feats of self-torture, cutting themselves with knives, till the blood gushes out upon them, and pretending to thrust spikes into their eyes, to break large stone blocks placed on their chests, to eat live charcoal, to swallow swords, and to perform many other tricks of legerdemain.

An opportunity presented itself in 1874 of observing one of these Faqirs, a very ignorant, disreputable looking, middle-aged man, whose intellect was blunted by excessive indulgence in Indian hemp. He wore long matted locks, hanging down to his shoulders, a short beard, and small moustache, while his dress consisted of a long, very dirty, and ragged blouse, a piece of cotton cloth wrapped round his loins like a petticoat, and a woollen blanket thrown over his left arm. On his head was a greasy cap with ear flaps, known as a "Kan-dhapa;" on his left wrist were five silver bracelets, and on his right leg an anklet, presented by a Nawab of Murshidabad and covered with leather to deceive bad characters.

In his hand he carried an iron mace with a sharp pointed handle, and square crown hung over with rings, called a "gorz," from which the order derives one of its Indian names. With this formidable weapon the Rafa'i Faqirs are in the habit of enforcing their demands for charity by slashing their tongues, and beating their heads, till blood comes. The tongue of the man referred to was a horrible sight, seamed as it was with deep scars, the result of former violence, while on the top of his head was a large depressed cicatrix, produced by the same means.

Around his neck hung three necklaces; one, called a "tasbih," was composed of onyx, quartz, and carnelian beads; a second, or Kanthi, had a hundred and one beads of olive wood (zaitun), while the third, of the same name, had a similar number of beads made of clay (Khak shifa) from the sacred tomb of Karbalah.

Such was the repulsive figure perambulating the streets of Dacca in 1874, and claiming to be a Sayyid. The Murshid, or spiritual guide, of this man resided at Kulpahar in the Hamirpur district of Bundelkhand.

Rafa'i Faqirs are Be-shara', freely indulging in intoxicating drugs. They are usually married men who neglect the regular prayers, and rarely, if ever, visit a mosque. By the Muhammadans of Bengal they are regarded with abhorrence and disgust.

1 His tomb was seen by Ibn Batuta in the fourteenth century. Lee's Translation, p. 33.

(e) Madaria

The founder of this Darwesh order was Sayyid Badi-ud-din, Qutb ul-Madar, born at Aleppo A.D. 1050, and according to the Mirat-i-Madaria his parents were Jews. Many legends are related of him. At the age of one hundred years he made the pilgrimage to Mecca, where he received from Muhammad permission to hold his breath, Habs-i-dam. Subsequently, he was directed to proceed to India and deliver it from an evil genius, Muckna Dev, which was destroying the people.

Having confined the demon, he induced the inhabitants to retain and settle with him in the town, still called Makanpur in the Doab, where he performed many miracles, and at his death on the seventeenth Rajab, A.H. 837 (1433), in the three hundred and ninety-sixth year of his age, he left 1,442 sons, or disciples.

Sultan Ibrahim Sharqi, of Jaunpur, carried his coffin, and erected a mausoleum over his remains.

The seventeenth of Rajab is observed as his festival ('urs1) throughout India; and at Makanpur thousands of pilgrims, Hindu and Muhammadan, assemble when the water of the Ikshunadi, flowing past the tomb, is said for that one day to run in seven streams of milk, and food cooked with it is believed to be of ineffable virtue.

The tomb at Makanpur stands in the centre of a square, the interior being lighted by four latticed windows. Above the grave hangs a canopy of cloth of gold, and a similar covering, highly perfumed, is laid on the tomb; close by is a Mosque before which a fountain plays, and two prodigious boilers stand, in which a constant miracle is being performed, for if unholy rice be put into them, they still remain empty.

No woman dare enter the mausoleum, and if foolhardy enough to try, she is seized with excruciating pains which last a long time.2

Around the name of this saint many superstitions have collected, and he is often confounded with Ghazi Miyan, whose flagstaff bears much resemblance to his. According to a great authority, Badi'uddin was a Cufi of a particular order, whose chief rites consist in the production of beatific visions by intoxication with Bhang.

The sect originated in Persia, its peculiarities, modified by the influence of Hindu ascetics, being introduced into India by this Badi' uddin. In several respects the Madaria Faqirs resemble the Hindu Sannyasis in going about almost naked, braiding their hair, and smearing their bodies with ashes, as well as in fastening iron chains around their waists and necks. The Banjara vagrants of Oudh, according to Mr. Carnegy, regard Shah Madar as their patron deity.

Madaria Faqirs are also called Dafali, from the small tambourine (daf) carried by them; and Dhammali, from running through and dancing in the midst of a fire on the great annual festival.

On the seventeenth of Rajab these Faqirs erect a lofty pole ('alam), enveloped in black, or red, cloth, from the top of which flutters a small black pennon, or the tail of a Yak. The principal spectacle is the exciting "dhammal," at which the Faqirs, worked into a state of enthusiasm, keep shouting "Dam Madar! Dam Madar!" and dancing barefooted in the midst of the fire of red hot charcoal, sustain no injury, owing, they say, to the direct interposition of the saint; but the Bhagat, or priest, of the Dosadhs performs similar antics without the slightest damage. May it not be reasonably inferred that this meaningless pageant is a survival of some aboriginal worship preserved by the Dosadhs, and copied by the followers of Madar.

In the festival the Faqirs prepare cakes, or Madar Ka-rot, consisting of floor and minced meat, which are eagerly bought and eaten by the spectators.

By respectable and peace-loving people these Faqirs are regarded as great nuisances. They wander about the city with the tambourine to which cymbals (jhanjh) are attached, and, like the hurdy-gurdy player of England, drive nervous people distracted by their unreasonable noise. A rich shopkeeper busily engaged in striking a bargain, or a fat Muhammadan gentleman about to take his siesta, is no sooner espied than the Faqir begins to beat and jangle his instrument, and to create such a disturbance that the victims are only too glad to get rid of him by paying a small sum of money.

In Dacca Madaria Faqirs dress in white with a black turban, and hanging on the chest is a "tasbih," or rosary of wooden beads. Besides extorting money from their townsmen, these Faqirs manufacture amulets, and "baddhis," or sashes, for those who put trust in them.

1 The festival is known as Chhari, Medni, Chiraghan, and Badi, when the Dhammal Khelna, or Gae lutana, takes place. Elliot, "Supplemental Glossary," vol. i, 247.

2 For further particulars regarding this shrine, see "Lord Valentis's Travels," vol i, 202; "Observations on the Mussulmans of India," vol ii, 321; and Shore's "Notes on Indian Affairs," ii, 489.