Delhi: Jaunti village

Contents |

Jaunti village

Mughal shikargah (hunting lodge)

The Times of India, Aug 05 2015

Richi Verma

Mughal shikargah falls prey to time

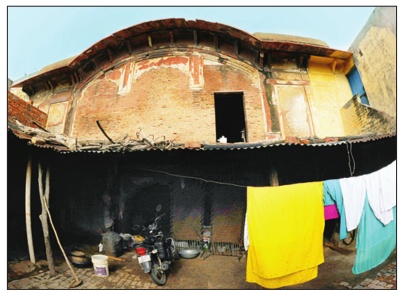

While villagers have built houses all around the complex, the majestic building is full of cattle sheds. A nearby water tank is also almost gone Tucked away in a tiny, remote cornerof Jaunti village on the outskirts of Delhi, a Mughal-era hunting lodge is heading for a slow-butsure death. Dated back to the 1650s, around the same time the Red Fort was built, this shikargah in northwest was said to be one of the favorite haunts of Emperor Shah Jahan, who used to lodge here frequently during his hunting escapades. Though rated `A' in terms of archaeological value by Intach, it has now turned into a cattle shed and the complex has been encroached upon by villagers from all sides. Close to Rohtak Road, Jaunti is surrounded by villages like Chatesar on the north, Garhi Rindhala on the south, Ladpur on the east and Kanonda, Khairpur and Mukundpur in Haryana on the western side. With a population close to 5,000, the village also has a medieval-era water tank. However, the growing needs of the villagers and sheer disregard of the government have led both the structures to a stage of near collapse.

The villagers consider shikargah as the village qila, but see no use of it other than for storing dung cakes. According to sources, 69 families live in and around the complex, and have extended their premises to accommodate growing families and cattle sheds.“This is the way I have seen this qila for the past 15 years since I came to live in the village. Once in a while, a tourist comes specifically to see the building,“ said Kamya, a villager who lives in one of the houses around the shikargah.

Historians say the shikargah was originally an imposing struc ture and similar monuments can be found in other parts of the city as well. “The hunters would leave Red Fort early in the morning and reach here before sunrise. Sometimes they camped in the shikargah for the night during summers. During early winters, they left the fort in the evening to reach their destination before nightfall,“ said a historian. Hunting was said to be the Mughal rulers' favourite pas time. Babar, the founder of the empire, was considered a skilled hunter and Akbar, Shah Jahan's grandfather, had the knack of tam ing wild animals, especially ele phants.

From the dilapidated struc ture, one can make out the origi nal design. Constructed of brick masonry, it had an extensive en closure and wide courtyards. Now, new houses have been built in the courtyards and a number of cows and buffaloes can be seen tied at a corner.

The main building is double storeyed and the original entrance is blocked by one household. Yet, there is a secondary narrow ac cess to the up per floor where one can see rem nants of a central vaulted compartment with domed pyramidal roofs at each end. Here, piles of dung cake can be seen in one corner. Portions of the sandstone slab ceiling have collapsed.

A series of damaged dalans are on the path leading to the basement, believed to be the tehkhana (underground chamber). Locals believe there was an underground passage which led to the water tank, but no evidence has been found. Historians say the shikargah was originally surrounded by a battlement wall, portions of which still remain.

Both the shikargah and the tank are considered historically significant, but a roadmap to conserve the structures still remains on paper.

Role in “Green Revolution”

Abhinaya Harigovind, Sep 29, 2023: The Indian Express

In 1965, the Jawahar Jounti Seed Cooperative Society was set up and the farmers who were a part of it sold wheat seeds.

Far from Chennai, where M S Swaminathan was born, Northwest Delhi’s Jaunti village remembers the agricultural scientist for having brought the ‘Green Revolution’ to it first.

High-yielding varieties of wheat were first planted in 1964 on around 70 acres in the village, which lies close to the national capital’s border with Haryana. “He was a gentle, hardworking man, who did good for us and for the world,” said Hukum Singh Chhikara, who was among the farmers on whose land the wheat was first sown. He had not heard yet of Swaminathan’s death.

Rammehar Singh, 93, whose father Chaudhary Bhoop Singh, was also among the first farmers from Jaunti to have the high-yielding variety sown in his field, said, “Gehun se bhar diya desh ko. And he chose our village to begin with. Farmers from other places would come here to buy seeds, and a lot was sold at that time.”

In 1965, the Jawahar Jounti Seed Cooperative Society was set up and the farmers who were a part of it sold wheat seeds.

Swaminathan having got Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to the village in 1967 to inaugurate a seed-processing centre of the cooperative society is also a matter of pride, said Master Radh Singh, 73. “He would visit the village almost every year,” said Singh. The seed-processing centre is now a Delhi government dispensary, a fading board marking its history.

or Om Prakash Chhikara, the grandson of Chaudhary Bhoop Singh, Swaminathan felt like family. “He has given a lot to the village. With the new varieties, the yield shot up and so did prosperity,” said Om Prakash, a retired school teacher whose family owns 16 acres of land.

Arya Kuldeep, 60, who owns around 14 acres of land, said, “Our village is known because of Dr Swaminathan. The ‘Green Revolution’ began here and his work is still a matter of discussion among those of my generation and those who are older.”

In the years since, much has changed. Amarjeet Chhikara, 52, the son of Khazan Singh who was also among the first farmers to have the wheat grown on his land, said, “A canal used to bring water to irrigate the fields then and the area was very fertile. The canal has stopped bringing water, and groundwater levels here are low. People here are now moving towards jobs, taking the focus away from agriculture. Since the administration doesn’t focus much on agriculture, we don’t get much in terms of subsidies or implements.”