Delhi: Lakes

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

An overview

2016

The Times of India, Jun 01 2016

Jasjeev Gandhiok

Most city lakes a picture of neglect

Delhi's water woes could be minimised if the city's 460 wetlands are rejuvenated and the groundwater recharged, activists say . With dumping of waste and algae deteriorating the water quality , most of these sites are a picture of neglect. Bhalswa Lake and Sanjay Lake--to gauge the gravity of the situation. While the condition of Sanjay Lake has slightly improved, Bhalswa Lake has been turned into a dumping ground.

“I have been coming here for the past two decades and even though I have seen improvement, there is a long way to go. Littering remains a problem at Sanjay Lake and strict action should be taken against the offenders,“ said Dilip Sharma, a resident of Mayur Vihar.

There are others who want activities such as bathing and washing clothes to stop at these sites. According to 55-year-old Gyanchand, a resident of Pat parganj, the number of migratory birds has also gone down over the years because of the garbage problem at the lake.

Water activist Manoj Misra, concretisation of catchment areas was causing problems. “Catchments have been concretised in order to beautify the lakes, but this has prevented the natural flow of rainwater into them. These lakes were once a part of the Yamuna, but now they are cut off from it because of the concrete structures,“ he said.

Even Bhalswa Lake has faced similar problems. Locals claim the stench is unbearable because of garbage being dumped on one side of the lake.

Manu Bhatnagar, principal director (natural heritage) of Intach, said that work to rejuvenate both these lakes had already started. “We have submitted our plans to DDA. Efforts will be taken to treat the lake water. There are also plans to introduce fish species to attract birds,“ said Bhatnagar.

He also stressed the importance of recharging groundwater levels, which are in decline.

Bringing city’s dying lakes back to life…

From: Paras Singh & Jasjeev Gandhiok, Bringing city’s dying lakes back to life may be a 3-idea dream, July 26, 2018: The Times of India

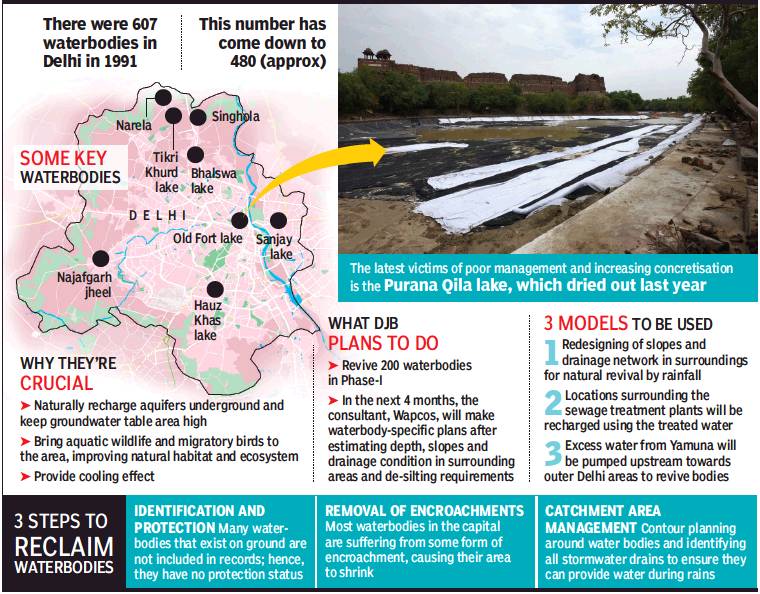

Considering the city’s poor record, the ambitious project of rejuvenating 200 waterbodies across the capital seems an uphill task. The work is still in the ideation phase and may take more than two years to come to fruition.

DJB vice-chairman and MLA from Sangam Vihar, Dinesh Mohaniya, said that a consultant has been hired to make detailed plans for each of the 200 big and small waterbodies and village ponds after studying them on parameters like depth, drainage network in surrounding areas, siltation of the lake bed, etc.

“The consultant, Wapcos (earlier known as Water and Power Consultancy Services), will submit its report in the next four months. Work will be carried out in phases and the first waterbody will take at least two years to get ready,” Mohaniya added.

Experts said there were 607 active large waterbodies in 1991, but now there are only 480 with more and more either drying out or getting encroached every year. This is also contributing to Delhi’s water crisis. Out of the 480 waterbodies, most are located in west Delhi, while the remaining are spread out in parts of south, southwest and north.

Central Ground Water Board (CGWB), in its latest submission, highlighted that around 15% of the capital has groundwater 40 metres below ground level. Experts added that preserving waterbodies may be the key to recharging groundwater levels.

Mohaniya said three models are being considered for bringing the dying lakes and ponds back to life. “Redesigning of slopes and drainage network surrounding the waterbodies will lead to natural revival by rain. For places closer to sewage treatment plants (STP), pipes will be laid to bring treated water to the lakes. This will also result in groundwater recharge. Currently, water from STPs is released in drains,” he added.

As per the third model, DJB is exploring at pumping excess water from Yamuna during monsoon upstream towards outer Delhi areas like Narela and Bawana to revive waterbodies there.

National Green Tribunal (NGT) had earlier directed agencies to revive 33 waterbodies in Dwarka, an area known to suffer from water problems. Experts, however, said nothing has been done in the last two years despite repeated directions.

Many redeveloped waterbodies near Aya Nagar and Najafgarh have turned into garbage dumps. “The most important component is participation of the community surrounding the waterbody. If people aren’t aware, own up and participate in rejuvenation, these waterbodies may also meet the same fate,” Mohaniya admitted.

Some of the waterbodies identified by DJB for revival include village ponds in Ibrahimpur, Hastsal, Nangli Poona, Babarpur, Mukand Pur, Kamruddin Nagar, Majra Burari, Kamalpur and Bhalswa and Najafgarh Lake.

Manu Bhatnagar of Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (Intach), who successfully worked on reviving the Hauz Khas Lake, said Delhi requires proper planning and utilisation of STPs to revive waterbodies and maintain them.

The 15-acre lake that had gone dry around 1960 was revived by Intach using highly-treated sewage water from the Vasant Kunj STP. The revival led to return of aquatic birds and significant groundwater recharge.

“In the last 13 years, 1,500 million litres of water has been recharged by Hauz Khas Lake alone. Other waterbodies can serve the same purpose, but since natural sources of collecting water are reducing, STP water can be utilised for them,” Bhatnagar said.

Other lakes have not been as lucky as the one in Hauz Khas. Bhalswa Lake — an oxbow lake on the Yamuna floodplain — is Delhi’s largest surviving one. While an arm of it became a part of the Bhalswa landfill, it continues to see inflow of sewage and waste from the nearby colony. It also becomes near dry during summer.

Archaeological Survey of India, following a NGT order, has also started restoring the lake around Purana Qila by outsourcing the work to NBCC. Experts, however, are apprehensive about concretising its base.

Diwan Singh, activist and convener of Natural Heritage First, said concretisation cannot be used as an excuse by authorities as it ensures that rainwater runoff is higher. “There has been no focus on reviving stormwater drains and diverting runoff to waterbodies. Using this method, we revived two waterbodies in Dwarka that can simply survive by rainwater,” he added.

Home to 40% of Delhi’s bird species

January 29, 2022: The Times of India

KS Gopi Sundar is a scientist with the Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF) and co-chair of the IUCN Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group. Writing in Times Evoke, he discusses the ecological importance of urban ponds:

World Wetlands Day, coming up on 2 cnd February, should inspire thought about wetlands and their role in ecology. The usual perception of a wetland is a sprawling lake far away from a city, distant from humans, entirely pristine and therefore, lush with biodiversity. However, our research presents interesting new findings about these entities. Wetlands are in fact embedded in our towns and cities. It is often believed that such urban waterbodies aren’t ecologically useful. City planning often doesn’t mention the value of these wetlands — when they measure hectares in size — as wildlife habitats. These are frequently used to dispose of garbage and many urban ponds have been quietly converted to malls or apartments. But these waterbodies play a crucial role in supporting bird life — and the ecosystem services this brings. Our research explored ponds across Delhi which is quite unique in terms of retaining many urban forests, a protected floodplain, patches of the Aravalli hills and verdant campuses. These diverse habitats — and the location of Delhi in the middle of a major migratory pathway of birds — have led to over 470 bird species being recorded in the city, the second-longest such list for any capital globally. A major reason for this avian abundance is that the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) disallows the destruction of waterbodies over a hectare in size. This has enabled 570 ponds to survive — the histories of these ponds are as varied as their appearance, from being village ponds to temple tanks, rainwater harvesting structures, waterbodies made in parks, etc. Last year, with Prakhar Rawal and Murali Krishna Chitakonda of Amity University, Swati Kittur and I from the NCF began studying Delhi’s ponds. A core objective was to research if birds kept away from waterbodies in more built-up areas — an important consideration in Delhi which is one of 33 megacities where human populations exceed 10 million. We used systematic methods that allowed repeatability and careful analyses to examine 39 ponds.

What we discovered surprised us greatly. Delhi’s ponds aren’t managed collectively — each is in the hands of municipalities, welfare associations and other institutions. Consequently, every pond has its own characteristics. Some are heavily managed, others are entirely ignored, some are accessible, others are hard to approach. The water quality, garbage levels and foliage also varied.

Importantly, this variety allows multiple birds to use these ponds. We found at least 177 species at the 39 waterbodies — ponds comprise less than 0. 5% of the area of Delhi but provide a home to over 40% of the city’s bird species. These included species of global conservation concern like the common pochard, the ferruginous pochard, the river lapwing, the black-headed ibis and the painted stork.

Also, ponds with less management interventions had greater diversity of habitats birds could use — as these interventions grew, the number of bird species declined. We found 46% birds were wetland specialists while the rest used the trees and shrubs on the edges of ponds. Management- favoured concretisation and other ‘beautification’ interventions made these spaces less conducive for birds. Bird species also increased dramatically at ponds with ‘islands’ — these could be an old submerged wall, a bit of protruding land or perished trees.

Our findings present insights that can be used by city planners to enhance the value of ponds. Tiny remnant wetlands inside a megacity are providing ecological services disproportionate to their size. They support an astonishing array of birds, despite not being maintained as bird habitats. Expensive interventions like using concrete, exotic bushes, etc. , are counter-productive. Planners should focus on more reasonably priced strategies like retaining native flora, shallow shores and mud banks for birds to forage in.

Delhi’s ponds have survived largely due to policies that disallow their conversion to development. The absence of a collective workbook has also caused ponds to develop their own conditions. Ponds thus provide a range of habitats — and happily, birds have discovered this diversity. Retaining the city’s ponds by spending less can provide ecological benefits other countries can’t accomplish without investing millions. We should also conduct scientific surveys of wetlands across our cities. These are astoundingly resilient — even when we fill them with trash, they still support hundreds of bird species. We should strengthen policy to reverse the degradation of urban wetlands — and we should appreciate the ecological services of birds, pollinators and trees which these urban waterbodies, tucked away amidst hectic cities, gift us so gracefully and quietly.

The health of Delhi’s water bodies

As in 2018

Jasjeev Gandhiok, June 24, 2020: The Times of India

From: Jasjeev Gandhiok, June 24, 2020: The Times of India

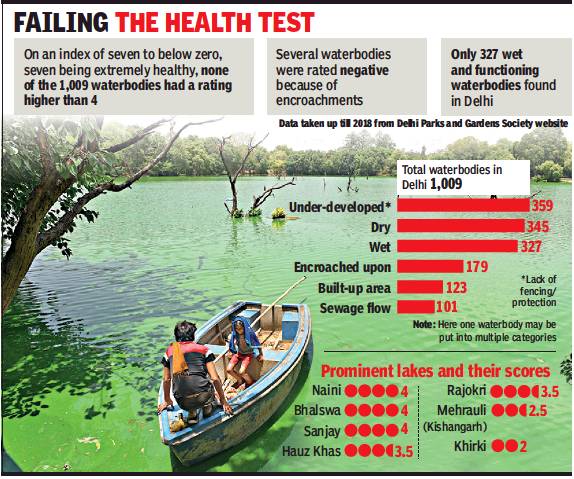

With expectations that the coming monsoon season would help revive Delhi’s waterbodies, many of which are now dry, a Delhi-based NGO and a residents’ welfare association have come up with an index to show the health of the capital’s 1,009 water bodies. These were mapped with the geo-coordinates provided by Delhi Parks and Gardens Society and each given a score of 0 to 7, with 7 being the healthiest. In the exercise, no waterbody in Delhi could get more than a 4 rating. Several waterbodies, in fact, received a negative rating on the health index, indicating encroachment or presence of construction on their area. Some villagers sent postcards to the Chief Justice of India to highlight the condition of these waterbodies.

The study, which was carried out by the Centre for Youth Culture Law and Environment (Cycle India) and the RWA of Jhuljhuli village in southwest Delhi, determined that only 327 water bodies currently have water, while 345 are dry and fully bereft of water. Another 302 have been given negative health ratings because they were found to have been partially or completely encroached upon.

Paras Tyagi, co-founder of Cycle India, said the study team began mapping the waterbodies after coming across several in urban villages that were dry at the moment or had been occupied over time. “Of the 327 waterbodies that have water in them, a majority of them are in urban villages and rural areas. However, these are also paradoxically the areas that have been the most affected,” said Tyagi. “Johads and small village ponds that earlier were useful for the local residents have dried up and there is no step being taken to revive them. In most places, such lakes get covered by soil and trash and developed as land.”

Appalled by the condition of the city’s waterbodies, 11 residents from 11 Delhi villages are sending 11,000 postcards to the Chief Justice of India, requesting swift action. Tyagi said around 9,000 of these postcards had been dispatched so far. Tyagi himself is one of the 11 representing Budhela village. The other villages involved are Jhuljhuli, Rawta, Ujwa, Shikarpur, Malikpur, Ghumanhera, Issapur, Paprawat, Dhansa and Kanjhawala. “The youth of these villages want to know if they are not entitled to planned and inclusive growth,” said Tyagi.

According to him, there aren’t too many waterbodies existing within the urban localities of Delhi, with lakes such as Hauz Khas, Bhalswa and Sanjay Lake reliant on man-made interventions and water from sewage treatment plants. Among the prominent ponds, Naini, Sanjay and Bhalswa lakes scored 4 on the index. The Mehrauli (Kishangarh) lake was given a score of 2.5, while Khirki lake scored 2. The pools at Rajokri and Hauz Khas were scored 3.5 on the index.

“The healthier lakes are located in urban villages and on the periphery of the capital. Within the urban limits, very few natural waterbodies exist, and those that are present are being preserved through human intervention. If similar efforts are made for other languishing waterbodies, the groundwater in those areas can be raised,” said Tyagi.

Over 100 water bodies were found to be contaminated by sewage lines or because of direct dumping of sewage and garbage. Tyagi said government documentation related to these water bodies also revealed confusing terminology like ‘partially built up’, ’partially encroached’, ‘legally built up’, illegally built up’, among others. “It is very strange to see such terms and how water bodies can be allowed to be ‘legally’ built up. This renders saving these waterbodies even more difficult as more and more of them are being sacrificed for land development,” rued Tyagi.

As in 2019

From: Jasjeev Gandhiok & Paras Singh, What the new city of lakes will look like, April 29, 2019: The Times of India

201 Waterbodies, Many Of Which Have Been Reduced To Garbage Dumps, To Be Rejuvenated

New Delhi:

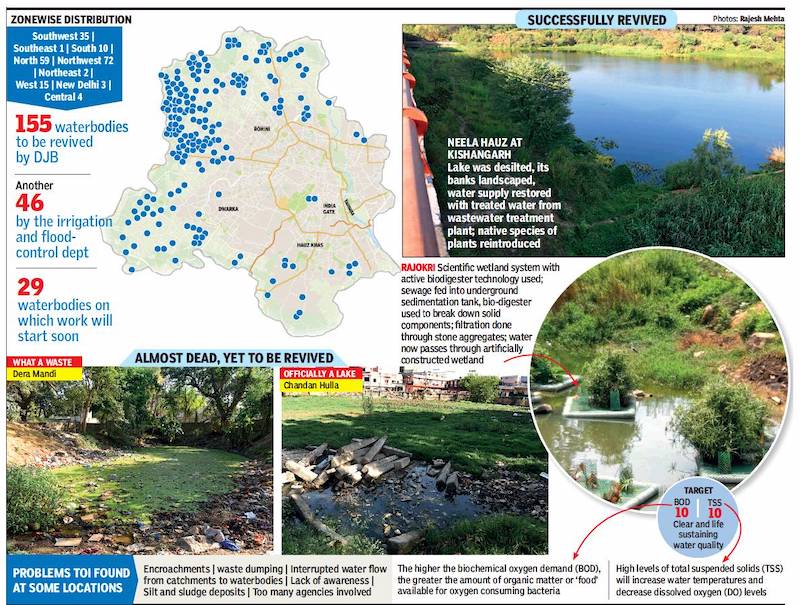

City of lakes. Thought of Udaipur in Rajasthan, didn’t you? But the Aam Aadmi Party government intends for the capital to earn this title. It has finalised 201 waterbodies for rejuvenation, with the plan being for Delhi Jal Board to revive 155 of them and the flood and irrigation control department the rest.

Senior DJB officials associated with the project said that tenders for work have been issued for 29 waterbodies in consultation with the National Environmental Engineering Research Institute. “NEERI has a panel of vendors who are equipped to execute such projects and they will undertake the work,” an official disclosed. The idea has been germinating since December last year, when chief minister Arvind Kejriwal, on a visit to the Coronation Park sewage treatment plant, announced a mega project capable of using treated water to augment Delhi’s water supply and a large-scale revival of lakes to restore the city’s ecological balance and groundwater.

Preservation of Delhi’s waterbodies hasn’t historically been under one agency. That is why 155 wet spots are under DJB’s jurisdiction, 143 under area revenue offices, seven with DDA, one each with the forest department and a municipal corporation, and three under the Archaeological Survey of India. These include historical ponds, step wells and a large number of village johads, or traditional rainwater storages.

TOI visited several of the proposed revival sites from a list provided by DJB and found that unique hurdles could derail the overall plan. In many cases, the ponds were in abadi, or inhabited, land due to encroachments, while some had vanished, perhaps never to be located again. Both the earmarked waterbodies in Dera Mandi were reduced to garbage dumps, with whatever little water they held lifeless and green with algal bloom.

“In the absence of proper waste management by the municipal corporations, ponds and johads become convenient garbage dumps. After tubewells began being used for irrigation, dependency on waterbodies ended and, hence their neglect,” the official explained. DJB now wants the people to have a stake in the restoration of the sort in the revived lake at Rajokri, where recreational spots and play areas have been incorporated to ensure people’s participation in its maintenance.

In Tughlaqabad village, the spots marked as baolis, or step wells, had houses standing there, while the Aya Nagar pond in the heart of the rural settlement has regressed to such as extent that the area’s residents had to petition Delhi high court in October 2014 for its revival. Civic agencies spent Rs 1.5 crore to spruce up the wet spot, but the continuous disposal of sewage and eutrophication (over enrichment with nutrients leading to excessive growth of alga and consequent depletion of oxygen) have again turned it into a stinking cesspool.

DJB has already exhibited its capability to bring ponds back to life. In Rajokri, it revived one with a decentralised sewage treatment plant coupled with bio-digesters, and, in addition, constructed a wetland integrated with the community sewage line to both feed and purify the pond. “Various lessons learnt from the Rajokri project will prove useful in the new project,” an official said. One surprise though. Neela Hauz in south Delhi features on the list even when the waterbody has already been revived by the Centre for Environmental Management of Degraded Ecosystems. “It is surprising to find Neela Hauz listed because it is at its purest form now and DJB cannot possibly do anything more there,” observed Faiyaz Khudsar, scientist in charge at the Yamuna Biodiversity Park.

Khudsar suggested that the constructed wetland system, used both for Neela Hauz and Rajokri, could be DJB’s preferred option for turning Delhi into a city of lakes. “It is cheaper and is natural too,” he said. “Going the sewage treatment plant way is costlier and comes with chances of malfunctioning.”

The five main lakes in 2019

Paras Singh and Jasjeev Gandhiok, May 23, 2019: The Times of India

From: Paras Singh and Jasjeev Gandhiok, May 23, 2019: The Times of India

Naini Lake: Model Town’s little lake is on life support. Turn off the three municipal borewells that steadily pump water into it, and it might turn into a dry bowl. The groundwater keeping it alive is a cure worse than the disease — experts say it is making the lake salty and unlivable for aquatic plants and animals.

The lake looked uninviting when TOI saw it in May 2019. The water was muddy and rich with plankton, the air rank with decay. “It smells, and as summer peaks, more fish will die,” said Juhi Chaudhary from the ‘Save Naini Lake’ campaign that has been fighting for the lake’s revival since 2015. She said nothing has been done about the algae in the lake, nor about improving the water quality and enriching its biodiversity.

This is despite the attention the lake gets. Politicians have visited it and made assurances about reviving it. Bureaucrats have released plans for public consultation. But the lake changes only for the worse. TOI found the surrounding walks and benches broken. A waterfall didn’t work. Some trees planted along the boundary had been uprooted. One corner was infested with rats. Boating used to be one of the lake’s attractions, especially for DU students, but a tussle between the AAP-led tourism department and the BJP-led North Delhi Municipal Corporation put an end to it about three years ago, said corporation officials. Most of the ducks and swans have also died.

Can it be saved? C R Babu, an ecologist working on the revival of several waterbodies in Delhi, said the lake is spring-fed and it will revive naturally if its bed is de-silted and storm water used to augment its fresh water supply. The water in the lake will need to be cleaned up and aerated with aeration fountains and jets. Growing water-cleaning fish and aquatic plants will also help.

But municipal officials say they don’t have the funds to take up these works. Their master plan for the lake has been in limbo for a year due to shortage of funds. Chaudhary disagreed: “The problem is of intent and vested interests. They had the funds. The Centre announced the funding, but nobody knows where the funds went, if they were sanctioned.”

Bhalswa Lake: The last time this lake beside Bhalswa golf course filled up to the brim was in 1964. That year, an embankment cut off the inflow of water from the Yamuna. Then, a landfill swallowed one arm of its horseshoe shape, reducing it to a half-kilometre-long pond. Finally, human and animal excrement from nearby settlements fouled up its waters so badly that Bhalswa Lake — once comparable in size to the lake in Nainital — is now a sorry sight.

TOI saw sewage from punctured drains around Bhalswa dairies flowing directly into the lake’s western bank. So much waste has been dumped into it that islands of mud and garbage take up half of its width along Outer Ring Road. Yet, Delhi government, somehow, still imagines it is a site for adventure sports like kayaking.

Even the eastern bank, where DTIIDC offers boating, is lined with garbage and leftovers from Chhath Puja. Manu Bhatnagar, principal director of conservation body Intach’s natural heritage division, said, “In summer, the water level goes down so much that you cannot even boat in it.”

Can it be saved? Bhatnagar said aquatic life in the lake will revive if dumping of waste from the dairies stops. Intach had recommended building a sewage treatment plant for the dairy drains, and using treated water from the nearby supplementary drain to recharge the lake. Its management plan for the lake lies forgotten. A recent joint survey by DDA, PWD and Delhi Jal Board has not translated into action either.

North corporation’s proposed biogas plant for the dairies might save the lake, though. The corporation will buy animal dung from the dairies and use it to generate electricity from biogas.

Purana Qila Lake: The lake outside Purana Qila was once part of a moat that kept enemies at bay. Now, after a Rs 30-crore makeover last year, it stops water from seeping into the soil.

As Delhi’s groundwater level has plunged, open grounds and waterbodies are needed to recharge it. Yet, the lake bed has been lined with an impervious geo-textile disregarding objections from environmentalists. Ironically, the renovation was done under orders from the National Green Tribunal, the country’s top environment court.

Skirting the fort’s 500-year-old walls between Talaqi (forbidden) and Humayun gates, the renovated lake is no better than a tar road. Bhatnagar said it is now dependent on tankers and other artificial sources because a lot of water is lost to evaporation.

The lake could have been restored without making it less useful to the environment, Bhatnagar said. Intach had recommended using water from the NDMC drain that crosses Bhairon Marg near the fort. “You would not have needed to concretise the lake. This would have been a much cheaper option too.”

Left to nature, it might have been easier to maintain as well. Although the lake was inaugurated only last October, TOI found algae and moss spreading in its stagnant water.

Sanjay Lake: At first glance, the green waters of Sanjay Lake look like a thriving ecosystem with trees and resident birds. All is not well, though, as this 17-hectare waterbody — about as large as 24 football fields — in east Delhi’s Trilokpuri is dependent on groundwater.

“A lake needs to sustain itself naturally and not deplete groundwater,” said Bhatnagar. The conservation body had recommended feeding the lake from the Kondli sewage treatment plant. To keep the water moving, it had proposed to supply the lake water to the bus terminus and railway station at Anand Vihar for non-drinking purposes. “This would not only ensure the water keeps moving but also generate revenue,” said Bhatnagar. But their proposal remains on paper.

With adventure activities on offer, the DDA-maintained lake is a popular family hangout. However, TOI found sections of the boundary wall broken and garbage dumped on the periphery. Locals said large quantities of sewage flow into the lake, and the dense growth of algae and plants on the water — due to a high concentration of nitrates and phosphates from sewage — seemed to confirm this.

Hauz Khas Lake: The ‘hauz’ in Hauz Khas has been around for 700-odd years, and for long it was Delhi’s model for reviving dead water bodies. Not anymore. Today, you can smell the lake before you see it. Near the banks, its water is thick as slime and dark green with algae. Bhatnagar said the stench arises from the algal bloom that thrives on sewage entering the lake from Mehrauli.

Earlier, water from sewage treatment plants was further cleaned with duckweed near Sanjay Van, before being released into the lake, he said. “This is not happening anymore, and it significantly alters the quality of water entering the lake. Worse, sewage from the Mehrauli side is also entering the lake now.”

The lake’s old aerators don’t work and its 10 floating islands that purify water by sucking out nitrates are too few to make a difference. “While 11 aerators were installed for improved oxygen levels, poor maintenance means they are not functioning anymore,” said Bhatnagar. “The lake’s deep end, which is next to the buildings, falls in the shadow area and is the worst affected.”

2024

Kushagra Dixit, April 13, 2024: The Times of India

From: Kushagra Dixit, April 13, 2024: The Times of India

New Delhi: While the city has struggled to maintain or restore 1,045 waterbodies enumerated in 2021 — many of them non-existent on the ground — Delhi govt has added 322 more to the tally based on satellite imagery. This makes a total of 1,367 waterbodies that need to be rejuvenated in the capital. Given the lack of action on vetting the wetlands, Delhi High Court asked the state govt on April 8 to ensure all the wetlands are appraised for maintenance by the end of the year.

In Aug 2021, the Wetland Authority of Delhi listed 1,045 waterbodies under the jurisdiction of 16 different agencies to be notified for restoration. However, TOI found some of them no longer exist as ponds, the dry beds having been filled and turned into plots for construction. Delhi govt has lagged in notifying them, vetting being a tedious task that requires screening and analysis in terms of biodiversity and area. Even the 20 lakes prioritised for notification by the Wetland Authority in Nov 2022 haven’t received the official wetland tag till date.

On April 8, the state govt submitted in Delhi High Court that 322 new waterbodies had been identified and added to the Wetland Authority’s list. An official of the authority said these new lakes appear on satellite images.

“The information was given to us by Geospatial Delhi Ltd (GSDL) and we have sought details from the revenue department about the whereabouts of these waterbodies, their owner agencies and their existing conditions. The revenue department will do the ground truthing to ascertain the existence of these waterbodies, we are still waiting for the data,” said the official. Acting chief justice Manmohan and justice Manmeet PS Arora had stated in their order that the court was informed that “several waterbodies out of 1,045 listed do not exist on the ground as on date”. It ordered Delhi govt to complete the geo-tagging and georeferencing of these lakes and ponds by May 15 and complete their rejuvenation by Dec 31.

The court order added that tenders for the restoration worked should be floated once the general elections model code of conduct was over and the contracts awarded by June 30.

“These works shall be completed by Dec 31 after removing encroachments (if any). Also, it is important to ensure that the rejuvenated water bodies are maintained properly and remain encroachment free. Therefore, the GNCTD shall take appropriate measures for making entries of waterbodies in revenue records, by assigning responsibilities of each of such waterbody to a specific officer, who shall visit such waterbody every fortnight to ensure its upkeep,” the order stated.

The Wetland Authority official said that of the listed lakes and ponds, there was confirmative information only on 344. Asked about the waterbodies from the initial list of 1,045 that had been built over and ceased to exist, the official said, “In place of the waterbodies, we found residential complexes, parks, even schools. But we will not delist any of them but make alternative plans to ensure the establishments at least conserve rainwater and recharge the groundwater recharge.”

Individual waterbodies

Naraina village pond

2000>21

Jasjeev Gandhiok, July 13, 2021: The Times of India

From: Jasjeev Gandhiok, July 13, 2021: The Times of India

Residents of Naraina village have written to Delhi Jal Board (DJB) and Delhi Cantonment Board highlighting the disappearance of a12-acre waterbody in the area, which satellite data shows has now dried up completely.

Satellite images from the years 2000, 2004, 2009 and 2021 show the waterbody gradually reducing in size, with an effluent treatment plant stretched out in the area. The locals have sought efforts to be made to revive the waterbody and ensure the area is not encroached upon further.

Paras Tyagi, an activist with the NGO Cycle-India, said the waterbody had been disregarded over time and its water level had reduced each year. Simultaneously, encroachments occurred in the area, reducing the expanse the waterbody once had. On Monday, he wrote to the DJB CEO asking for attention to be drawn to the waterbody.

In his letter, Tyagi showed satellite images stating that an opportunity for local use of water and natural groundwater recharge was missed by not saving the village pond.

“The Delhi chief secretary has passed an order that clearly states no ponds should be filled up or reclaimed by any individual or organisation. But today, barring a few waterbodies in the public eye, all others are left ignored and are in a dilapidated condition. Residents have to bear the consequences as they suffer the most due to inappropriate and unsatisfactory supply of water,” said Tyagi.

Aditya Tanwar, a Naraina resident who tracked the disappearance, said the waterbody was spread over12 acres and was flourishing till the year 2000. It was a part of five local johads in the area. “In government records, only two out of these five waterbodies are recognised. A number of waterbodies in other villages have also slowly disappeared. The authorities have systematically encroached upon this village pond too, which was the largest of the five,” he added.

Last year, the NGO had released a “health” scorecard of 1,009 waterbodies across Delhi, mapping each through geocoordinates provided by Delhi Parks and Gardens Society. Each waterbody was given a score from 0 to 7, where 7 was the healthiest.

The analysis found that only 327 waterbodies had water through the year, while 345 were dry and fully bereft of water. Another 302 had been given negative health ratings because they were found to have been partially or completely encroached upon. Among the prominent ponds, Naini, Sanjay and Bhalswa lakes had scored 4 on the index. The Mehrauli (Kishangarh) lake was given a score of 2.5, while Khirki lake scored 2. The waterbodies at Rajokri and Hauz Khas scored 3.5 on the index.

Satpula Lake

As of 2025

Kushagra Dixit, June 26, 2025: The Times of India

The lake, virtually dead for years, was revived under an initiative by Rotary Club of Delhi, South Central.

The lake, which had long dried up due to urban sprawl and neglect, now glistens with fresh, treated water, signalling the powerful impact of civic action and sustainable innovation. Stressing its historic importance, the officials at Rotary said that the transformation was not just about the water but also “about reclaiming our heritage, healing our environment, and inspiring communities.”

The lake was revived by Rotary in partnership with the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (Intach) after an NOC was granted by DDA, enabling the project to proceed. Ashok Kantoor, district governor (2022-23), and NK Lamba, Rotary district chair for water, said that the lake was revived as it “deserved a second chance, and Rotary was determined to make it happen.” “For decades, the Satpula Lake, once fed by rainwater flowing from the nearby Jahanpanah forest, lay dry, its source cut off by roads and construction. Today, thanks to the installation of an ecoengineered Aranya Dwip system, drain water is filtered and biologically treated before being channelled into the lake. This not only replenishes the water body but ensures it stays alive all year round. What was once barren land has been reshaped into a serene, vibrant ecosystem where birds chirp, aquatic plants thrive, and heritage whispers through rippling waters,” a statement from Rotary said.

It stated that a 200 KLD Aranya Dwip remediation system now treats wastewater through a multi-layered sequence of filtration, bioremediation, constructed wetlands and natural aeration. “This is proof that low-cost, low-energy solutions can transform urban decay into ecological gold. Satpula Lake is just the beginning,” Lamba said.

"Satpula, meaning seven bridges, was built during the reign of Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq. It functioned as both a water reservoir and part of the city's medieval defence structure," Rotary said.

According to Manu Bhatnagar, director of Intach, the 14th century lake was a dry and dead area, and the only source of water was an adjacent drain. The water table was 60 feet deep, and the bed extremely porous.

“Water was picked from the drain and treated using a settling system and then using Aranya Dwip, which is based on microbial culture, and also using a constructed wetland that uses grasses like Typha. Gradually, the lake formed although the bed was extremely porous and the water table was 60 m below the surface. Now the water quality has recently been tested as showing a BOD level of around 12 mg/l and DO level of 5.5 mg/l. To ensure the water quality is good, further measures such as the introduction of fish was done, including Indian Carps and Garai. These were introduced when they were fingerlings, and now they have grown up to 16-17 inches. We weighed one fish at 3.4 kg,” Bhatnagar said.

He added that several birds like spot-billed duck, water hens, grebes, kingfisher and pond egrets have also been seen. “Now we are ready for the rain, and having surfaced the aquifer, we are hoping to spread from 6,500 sqm to 8,000 sqm. Beyond this, there is an overflow arrangement that will take excess water to the drain,” said Bhatnagar.