Delhi: Sadar Bazar

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Additional information may please be sent as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Qaumi School/ Shahi Eidgah

From: Mohammad Ibrar, Working under tin roof for 42 yrs, Urdu school risks losing even that, February 27, 2018: The Times of India

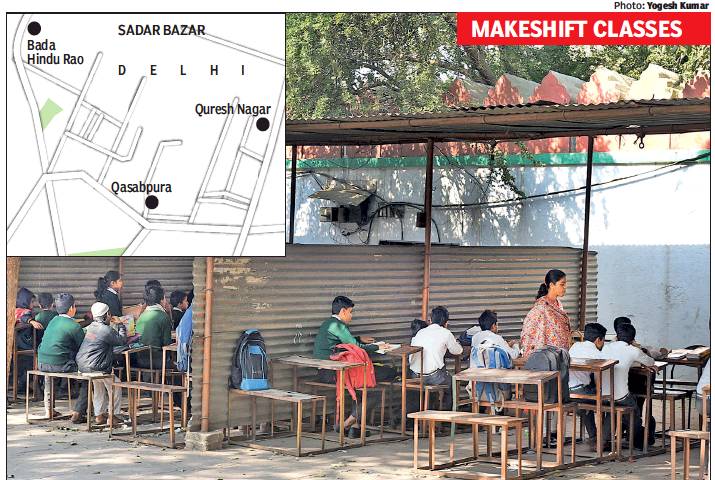

The 17th-century Shahi Eidgah in Old Delhi’s Sadar Bazaar is often crowded — not with supplicants assembling for prayers, but with children who turn up daily to study in a school at one corner of the paved ground.

Functioning under battered asbestos roofs and haphazardly assembled rickety furniture, the Qaumi Senior Secondary School has provided for thousands of students in its 42 years at the Eidgah. The only governmentaided Urdu-medium school in the vicinity, it caters to residents of Qasabpura, Quresh Nagar, Bada Hindu Rao and adjoining areas.

The school once functioned from a bustling four-storeyed building, which was razed during the Emergency in 1976. Having weathered all sorts of storms over the years, its existence is now under the threat as the Delhi government is looking to dismantle it and accommodate its students and teachers elsewhere.

Mohammad Shareef (13), son of a daily wager, is a regular to the school. He says: “Though it’s not like any other school, they teach us better here.” Shareef lives near the school, and that’s one of the reasons why his father prefers it. According to Ehsan Ali, a teacher at the school, the biggest challenge the children face here is “the attack of the weather”. He says: “During summer, the asbestos turns the classrooms into furnaces. During winter, it’s too cold without the walls.” Nonetheless, Ali has been associated with the school for 18 years.

Activist Firoz Ahmed Bakht recently filed a petition in Delhi High Court, demanding that the government construct a new building, “as promised when the government of 1976 had levelled the ground where it once stood”. In his PIL filed through advocate Atyab Siddiqui, Bakht contended that children from the “downtrodden and backward classes have to suffer due to threats of closure, makeshift classrooms, leaking roofs and no proper facilities”.

HC is looking into the issue and has asked AAP government and other agencies to explore the possibility of allotting land for the minority school. The matter will come up for hearing again on Tuesday.

While the counsel for the government had assured the court of the keenness to resolve the issue, Bakht isn’t so sure. He argues that as per the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009, it is now obligatory for the state to provide land and building for neighbourhood schools. “The government is trying to merge the Urdu-medium school by distributing the students to other schools in the adjoining areas,” he says.

He alleges that on January 17, the Directorate of Education sent a mail to the school principal, Mohabbat Ali, asking him for details of students and employees “to distribute them to other schools”. Ali says such a plan will be disastrous for students. “We have more than 700 students who have been studying here for years now. If allowed and supported, we can modify the existing place and improve it. To send students of an Urdumedium school to that of any other medium will affect their education,” he says.

Siddiqui says the government has maintained that it doesn’t have the land to relocate the school. Even DDA and Delhi Waqf have claimed “sympathies with the students”, but said they have no land. “The only hope for us is HC’s intervention,” Siddiqui says. Bakht believes that if the government shows intent, it can get land from an adjoining park, which “has become a hotbed for nefarious activities and is a favourite haunt of drug-peddlers.”

Nand Di Hatti

The Times of India, Sep 12 2015

Sujith Nair Nand Di Hatti has been drawing generations of Delhiites with lip-smacking chhola-bhaturas

Chhola bhatura -the sight and smell of this sinfully flavour some combination can kill any diet plan. Nand Di Hatti, nestled in the milling lanes of Old Delhi's Sadar Bazaar, is among the best places for a plateful of this spicy delight.This eatery has been drawing generations of Delhiites with its fluffy bhaturas and spiced chickpeas.

The shop's secondgeneration owner, 71-year-old Om Prakash, says his father, Nand Lal Makkar, initially sold meetha kulcha and chhola for six annas from a pushcart in Sadar Bazaar. He had moved to Delhi along with his family from Rawalpindi during Partition.

Nand Lal set up the shop in mid-70s and started serving bhaturas instead because Karol Bagh's Bhasin Bakers which supplied meetha kulcha stopped production -it no longer had wo rk e r s s k i l l e d enough to undertake the baking process. “Red in colour, the meetha kulcha is bigger and three times costlier than the normal one,“ says Gajendra Bhasin, the current owner of Bhasin Bakers. His grandfather sold meetha kulcha in Rawalpindi and after Partition set up shop in Karol Bagh.

In the early 90s, Nand Lal's shop was split between his two sons. Om Prakash, the second son, now runs Nand Di Hatti along with his sons, while his nephew, Bharat, 44, sits in the second shop called Nand Bhature Wale Di Hatti.

Made in desi ghee without onion, Nand Lal's chhola bhaturas are served with aloo, chillies and mango pickle.Bharat's day starts at 3am when he starts cooking chana in his kitchen, which he shares with his cous h he shares with his cous ins. The chana, which is not soaked as is the nor m, is cooked with spices over low fire for five hours. Slow cooking, Bharat says, ensures that the chickpea's skin stays intact. Anubhav Sapra, who conducts food walks in the city, says his parents maintain that Nand's chhola bhatura has remained consistently delicious over the last 30 years. “Nand mixes sooji with maida while making the bhaturas. This keeps them light on the tummy,“ says Sapra. Bharat says he tried setting up similar shops in West Dehli's Hari Nagar and Ramesh Nagar, but had to fold up within six months. Om Prakash, too, had to wind up his second outlet in Paharganj within a year.

Both shops also sell chana masala in packets for patrons who want to replicate the magic. Mahesh Khanna, 70, the second-generation owner of Khanna Stationery Mart in Sadar Bazaar, remembers eating Nand's chhola and meetha kulcha in the early 60s. “They used to sell it for 50 paise. Now it costs Rs 90,“ he says.

Food historian Pushpesh Pant says Delhi had a culture of chaats, kulcha and mutter. “Chhola bhatura came in with the refugees during Partition and soon replaced kulcha and mutter from the scene.“