Delhi: Tughlaqabad

Contents |

Delhi:Tughlaqabad in 1902

This article was written between 1902 when conditions were Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles |

Extracted from:

Delhi: Past And Present

By H. C. Fanshawe, C.S.I.

Bengal Civil Service, Retired;

Late Chief Secretary To The Punjab Government,

And Commissioner Of The Delhi Division

John Murray, London. I9o2.

NOTE: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to the correct place.

Secondly, kindly ignore all references to page numbers, because they refer to the physical, printed book.

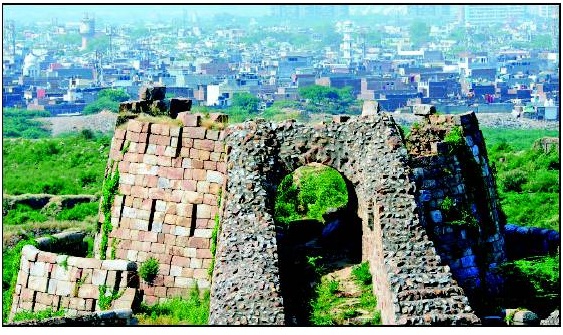

A fine view of ihe western portion of the citadel of Tughlakabad is obtained from the point where the road makes a sudden turn towards it from the south, about three-quarters of a mile on the Kutab side of the tomb of Tughlak Shah.

The ruins of this wall and of its immense splayed bastions, picked out with bushes and grass, are extremely effective everywhere, but are finest along the south side of the upper citadel; this is entered from the lower fortress which is reached by a gate nearly opposite the bridge that connected the mausoleum with the latter.

The city and fort were built between the years 1321 and 1323 A.D., were deserted by Muhammad Tughlak Shah in favour of Daulatabad, and were finally superseded by Firozabad; but the real cause of its permanent abandonment was no doubt the badness of the water and general insalubrity of the site, as in the case of Fatahpur Sikri. The curse of the saint

“Ya basé Gujar ;

Ya rahé ujar.”

(“Be it the home of the Gujar, or rest it deserted”) [Either Gujjars will live here/ or this place will be a desolate ruin], is doubly fulfilled; for while most of the area inside the walls lies utterly desolate and covered with masses of ruins, there are also two small Gujar villages inside it. The great size of the stones used in the wall—the triple storeyed towers—the high parapet, backed inside by terraces with rooms—and the lofty gates, are all very imposing—perhaps the most impressive bit of all is the south-east bastion of the citadel and the east wall above it.

The path through the gate above-mentioned leads past a large reservoir hewn in the rock: beyond it to the north-west are ruins of the palace and stables and of a fine mosque. From the tank the track ascends to an outwork below the principal gate of the citadel, which must have been a very fine and strong portal, and then winds through ruins to the highest point of all, upon which some royal building no doubt stood.

Below this, on the west, was a very deep (baoli) tank for the use of the defenders of the citadel, and all round are underground passages, off which the servants and slaves of the king had quarters. These should not be lightly entered, as they still occasionally harbour leopards and hyænas, and a tiger has within the last twenty years been known to take refuge in them.

An extremely fine view to the north is obtained from the top of the citadel—on clear days it includes the domes of the Jama Masjid of Delhi—and to the east are seen many blue curves of the Jumna stream. The Tomb of Tughlak Shah, rising above the fortress walls which surround it, is perhaps one of the most picturesque buildings outside modern Delhi; and when it stood reflected on all sides in the lake below, it must have presented a spectacle of unusual beauty. It is impossible to improve on Mr Fergusson’s description of it:

“When the stern old warrior, Tughlak Shah, founded the new Delhi, which still bears his name, he built a tomb, not in a garden as was usually the case, but in a strongly fortified citadel in the middle of an artificial lake.1 The sloping walls and almost Egyptian solidity of this mausoleum, combined with the bold and massive towers of the fortifications that surround it, form a picture of a warrior’s tomb unrivalled anywhere, and a singular contrast with the elegant and luxuriant garden tombs of the more settled and peaceful dynasties that succeeded.” [1 It is worthy of note that another Pathan king, greater and sterner perhaps than Tughlak Shah, the Sultan Sher Khan Sur, built his tomb at Sassaram, in the middle of a magnificent tank. This tomb depended for its effect upon the brilliantly painted decoration of its exterior, of which the outlines are still quite distinct, and must have presented a most gorgeous spectacle when fresh from the artists’ hands, shining against the blue sky and mirrored in the blue water.]

The red sandstone gateway, with its sloping face and jambs and head in the earlier Pathan style, contrasts finely with the dark walls and rounded towers in which it stands, and the trees which overshadow it. The interior of the fortress is much smaller than one would suppose from the outside, and, except for the pointed corner to the east, is almost filled by the tomb.

This is the earliest building of which the walls have a very decided slope. They are of red sandstone, relieved in the upper portion by a very sparing use of white marble. The marble slabs of the dome are not well fitted. This may be due to the fact that the dome was the first attempt of its kind in India, but the people of the west village in the fort, who were removed there from the tomb, have a dreadful tale, that the slabs were stripped off after 1857 and were ordered to be sold, but were finally replaced.

The interior of the tomb, which is rather larger than that of the Sultan Balban, is very plain, but decidedly effective. It contains three graves, the centre one being that of Tughlak Shah, and one of the others it is believed that of his son, the Khuni Sultan, at the head of which Firoz Shah placed the propitiatory chest In the north-west corner of the enclosure is a small tornb-chamber, with an arcade round it, containing a number of graves.

The city, like the έκαтόμπυλοι θήβαι was designated from the vastness of its defences as that of the Fifty-two Gates, and, as we have already seen (p. 233), Mr Finch refers to it under this description.

Adilabad or Muhammadabad

Corresponding to the mausoleum at the east end of the lake, and connected with the southeast corner of the defences of Tughlakabad city by an immense embankment, is the ruined fortress of Adilabad, or Muhammadabad.

This is entered by a fine gate on the west face, and affords a very charming view from above; it was possibly a water palace, like the splendid buildings at Mandu known by that name. The east face of the embankment is forty feet high; between it and the walls of Tughlakabad city is a fine sluice cut in the solid rock.

A mile beyond this is an isolated fortified little hill, known as the Nai’s (or Barbers) Fort. This was apparently a College (Madrasa), or the retreat of some holy personage, and was probably fortified as such against a possible Moghal attack.

Surajkund and Arrangpur Band

About two and a half miles south-east of Adilabad is a fine masonry tank, and near it a very fine masonry “band,’ known as the Surajkund and Arrangpur Band. These date from the eighth century, and are therefore among the oldest Hindu works near Old Delhi. Both are extremely picturesque, and well worth visiting.

A long flight of steps led down to the tank from a temple on the west side. The band is nearly three hundred feet long, and more than sixty feet high in the centre, where a small spring (Jhir) rises from under it. Less than three miles east of this point the road reaches that from Delhi to Muttra, at Badarpur, built inside the enclosure of an old Imperial Sarai.

This place is about eight miles distant from Nizam-ud-din and the mausoleum of Humayun; and visitors spending the night at the Kutab, and proceeding to Tughlakabad in the morning, can arrange to return to Delhi by this way.

Tughlaqabad fort

Shreya Roy Chowdhury

The Times of India, Oct 8, 2011

After winning a decade-old legal battle, ASI had put the village on notice to vacate the 14th-century fort

The village was created in 1405. But with Archaeological Survey of India’s deadline for vacating the village expiring, such long and fond associations have run into a dead end. Nizamuddin Auliya’s famous curse upon Sultan Ghiasuddin Tughlaq that his capital would remain barren and desolate seems to have acquired an edge of finality.

Sant Colony, on the edge of the village, is relatively new, having come up in the early 1980s. Numerous languages and dialects are spoken here as families from all over the country have made it their home.

Most migrants work as labourers or sell vegetables. It is also the part where demolition was started in 2001, before Delhi High Court stayed ASI’s hand.

Encroachments, as in 2016

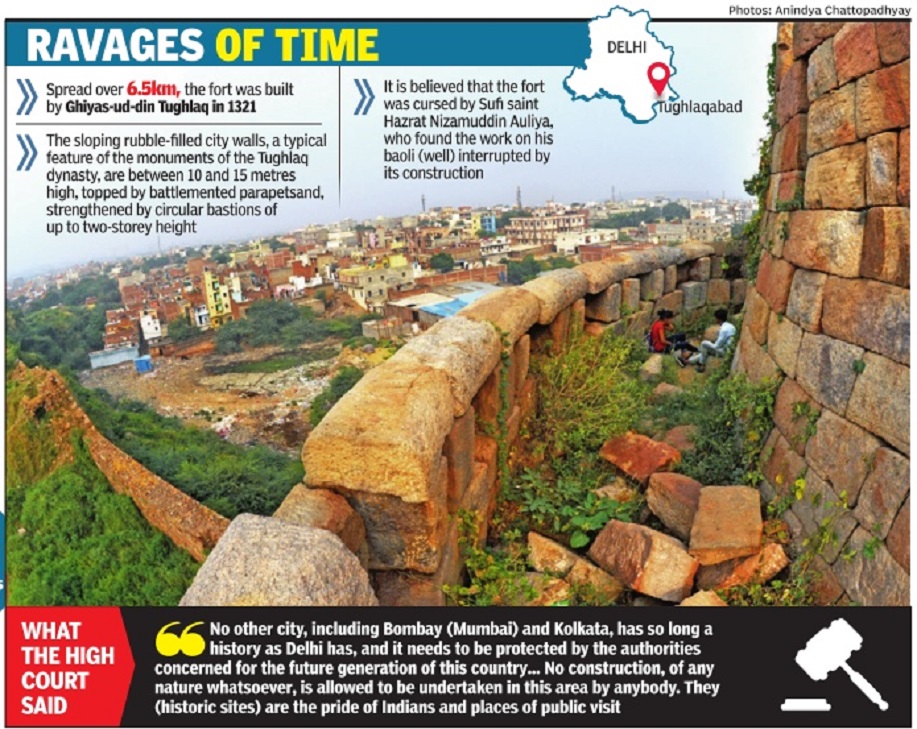

Tughlaqabad Fort is a pre-gunpowder fort.It was built in 1321 during an important phase when warfare was changing and fortified buildings had to be designed differently . Yet anyone visiting the monument in south Delhi today would be hard put to understand this significance. Delhi high court, recognising its sad neglect, lambasted the Archaeological Survey of India for failing to protect it, but the encroachments there are not of recent origin.

“The villages surrounding the fort have expanded and encroached on public land for several years now, and the few times it tried to demolish the illegal construction, ASI failed,“ said an expert. The result is that at least 50% of the land that originally comprised the fort com plex has been occupied. The shrinking surroundings and the utter lack of maintenance there has robbed Tughlaqabad Fort and the neighbouring Adilabad Fort of the possible honour of becoming the capital's fourth World Heritage Site after Red Fort, Qutub Minar complex and Humayan's tomb.

Many historians feel that the land around the monument could not have been encroached and built upon without political connivance. ASI has failed to demarcate the monument limits.

In the state that it is, the fort does not attract too many visitors. The structure build by Ghiyas-uddin Tughlaq, the founder of the Tughlaq dynasty , is marred by unkempt foliage and dense, thorny vegetation. The baoli, or well, is swamped by overgrowth.A few years ago, ASI undertook an excavation project at the fort. It is now impos sible to know where this dig took place.

ASI officials admit it is difficult to keep such a large expanse in pristine shape when inhabitants of the nearby village let their cattle loose on the fort grounds to graze. At times, there are more donkeys, cows and buffaloes there than visitors.