Devanga

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Dēvānga

The Dēvāngas are a caste of weavers, speaking Telugu or Canarese, who are found all over the Madras Presidency. Those whom I studied in the Bellary district connected my operations in a vague way with the pilāg (plague) tax, and collection of subscriptions for the Victoria Memorial. They were employed in weaving women’s sāris in pure cotton, or with a silk border, which were sold to rich merchants in the local bazaar, some of whom belong to the Dēvānga caste. They laughingly said that, though they are [155]professional weavers, they find it cheapest to wear cloths of European manufacture.

The Dēvāngas are also called Jādaru or Jāda (great men), Dēndra, Dēvara, Dēra, Sēniyan, and Sēdan. At Coimbatore, in the Tamil country, they are called Settukkāran (economical people). The following legend is narrated concerning the origin of the caste. Brahma, having created Manu, told him to weave clothes for Dēvas and men. Accordingly Manu continued to weave for some years, and reached heaven through his piety and virtuous life. There being no one left to weave for them, the Dēvas and men had to wear garments of leaves. Vexed at this, they prayed to Brahma that he would rescue them from their plight. Brahma took them to Siva, who at once created a lustrous spirit, and called him Dēvalan. Struck with the brilliancy thereof, all fled in confusion, excepting Parvati, who remained near Siva. Siva told her that Dēvalan was created to weave clothes, to cover the limbs and bodies of Dēvas and men, whose descendants are in consequence called Dēvāngas (Dēva angam, limb of god).

Dēvalan was advised to obtain thread from the lotus stalks springing from the navel of Vishnu, and he secured them after a severe penance. On his way back, he met a Rākshasa, Vajradantan by name, who was doing penance at a hermitage, disguised as a Sanyāsi. Deceived by his appearance, Dēvalan paid homage to him, and determined to spend the night at the hermitage. But, towards the close of the day, the Rishi and his followers threw off their disguise, and appeared in their true colours as Asuras. Dēvalan sought the assistance of Vishnu, and a chakra was given to him, with which he attempted to overthrow the increasing number of Asuras. He then invoked the assistance of Chaudanāyaki or Chaudēswari, who came riding on a lion, and the Asuras were killed off. The mighty Asuras who met their death were Vajradantan (diamond-toothed), Pugainethran (smoke-eyed), Pugaimugan (smoke-faced), Chithrasēnan (leader of armies) and Jeyadrathan (owner of a victory-securing car). The blood of these five was coloured respectively yellow, red, white, green, and black. For dyeing threads of different colours, Dēvalan dipped them in the blood. The Dēvāngas claim to be the descendants of Dēvalan, and say that they are Dēvānga Brāhmans, on the strength of the following stanza, which seems to have been composed by a Dēvānga priest, Sambalinga Murti by name:—

Manu was born in the Brāhman caste.

He was surely a Brāhman in the womb.

There is no Sudraism in this caste.

Dēvanga had the form of Brāhma.

The legendary origin of the Dēvāngas is given as follows in the Baramahal Records. “When Brahma the creator created the charam and acharam, or the animate and inanimate creation, the Dēvatas or gods, Rākshasas or evil demons, and the human race, were without a covering for their bodies, which displeasing the god Narada or reason, he waited upon Paramēshwara or the great Lord at his palace on the Kailāsa Parvata or mount of paradise, and represented the indecent state of the inhabitants of the universe, and prayed that he would be pleased to devise a covering for their nakedness. Paramēshwara saw the propriety of Narada’s request, and thought it was proper to grant it. While he was so thinking, a male sprang into existence from his body, whom he named Dēva angam or the body of God, in allusion to the manner of his birth.

Dēva angam instantly asked his progenitor why he had created him. The God answered ‘Repair to the pāla samudram or sea of milk, where you will find Sri Maha Vishnu or the august mighty god Vishnu, and he will tell thee what to do.’ Dēva angam repaired to the presence of Sri Maha Vishnu, and represented that Paramēshwara had sent him, and begged to be favoured with Vishnu’s commands. Vishnu replied ‘Do you weave cloth to serve as a covering to the inhabitants of the universe.’ Vishnu then gave him some of the fibres of the lotus flower that grew from his navel, and taught him how to make it into cloth. Dēva angam wove a piece of cloth, and presented it to Vishnu, who accepted it, and ordered him to depart, and to take the fibres of trees, and make raiment for the inhabitants of the Vishnu loka or gods.

Dēva angam created ten thousand weavers, who used to go to the forest and collect the fibre of trees, and make it into cloth for the Dēvatas or gods and the human race. One day, Dēva angam and his tribe went to a forest in the Bhuloka or earthly world, in order to collect the fibre of trees, when he was attacked by a race of Rākshasas or giants, on which he waxed wroth, and, unbending his jata or long plaited hair, gave it a twist, and struck it once on the ground. In that moment, a Shakti, or female goddess having eight hands, each grasping a warlike weapon, sprang from the earth, attacked the Rākshasas, and defeated them. Dēva anga named her Chudēshwari or goddess of the hair, and, as she delivered his tribe out of the hands of the Rākshasas, he made her his tutelary divinity.”

The tribal goddess of the Dēvāngas is Chaudēswari, a form of Kāli or Durga, who is worshipped annually at a festival, in which the entire community takes part either at the temple, or at a house or grove specially prepared for the occasion. During the festival weaving operations cease; and those who take a prominent part in the rites fast, and avoid pollution. The first day is called alagu nilupadam (erecting, or fixing of the sword). The goddess is worshipped, and a sheep or goat sacrificed, unless the settlement is composed of vegetarian Dēvāngas.

One man at least from each sept fasts, remains pure, and carries a sword. Inside the temple, or at the spot selected, the pūjari (priest) tries to balance a long sword on its point on the edge of the mouth of a pot, while the alagu men cut their chests with the swords. Failure to balance the sword is believed to be due to pollution brought by somebody to get rid of which the alagu men bathe. Cow’s urine and turmeric water are sprinkled over those assembled, and women are kept at a distance to prevent menstrual or other form of pollution. On the next day, called jothiārambam (jothi, light or splendour) as Chaudēswari is believed to have sprung from jothi, a big mass is made of rice flour, and a wick, fed with ghī (clarified butter) and lighted, is placed in a cavity scooped out therein.

This flour lamp must be made by members of a pūjāri’s family assisted sometimes by the alagu boys. In its manufacture, a quantity of rice is steeped in water, and poured on a plantain leaf. Jaggery (crude sugar) is then mixed with it, and, when it is of the proper consistency, it is shaped into a cone, and placed on a silver or brass tray. On the third day, called pānaka pūja or mahānēvedyam, jaggery water is offered, and cocoanuts, and other offerings are laid before the goddess. The rice mass is divided up, and given to the pūjari, setti, alagu men and boys, and to the community, to which small portions are doled out in a particular order, which must be strictly observed. For example, at Tindivānam the order is as follows:—

• Setti (headman).

• Dhondapu family.

• Bapatla family.

• Kosanam family.

• Modanam family.

Fire-walking does not form part of the festival, as the goddess herself sprang from fire. In some places in the North Arcot district the festival lasts over ten days, and varies in some points from the above. On the first day, the people go in procession to a jammi (Prosopis spicigera) tree, and worship a decorated pot (kalasam), to which sheep and goats are sacrificed. From the second to the sixth day, the goddess and pot are worshipped daily. On the seventh day, the jammi tree is again visited, and a man carries on his back cooked rice, which may not be placed on the ground, except near the tree, or at the temple. If the rice is not set down en route thereto, it is accepted as a sign that the festival may be proceeded with. Otherwise they would be afraid to light the joti on the ninth day. This is a busy day, and the ceremonies of sandhulu kattadam (binding the corners), alagu erecting, lighting the flour mass, and pot worship are performed.

Early in the morning, goats and sheep are killed, outside the village boundary, in the north, east, south, and west corners, and the blood is sprinkled on all sides to keep off all foreign ganams or saktis. The sword business, as already described, is gone through, and certain tests applied to see whether the joti may be lighted. A lime fruit is placed in the region of the navel of the idol, who should throw it down spontaneously. A bundle of betel leaves is cut across with a knife, and the cut ends should unite. If the omens are favourable, the joti is lighted, sheep and goats are killed, and pongal (rice) is offered to the joti. The day closes with worship of the pot. On the last day the rice mass is distributed. All Dēvānga guests from other villages have to be received and treated with respect according to the local rules, which are in force. For this purpose, the community divide their settlements into Sthalams, Pāyakattulu, Galugrāmatulu, Pētalu, and Kurugrāmālu, which have a definite order of precedence.

Among the Dēvāngas the following endogamous sections occur:—

(1) Telugu;

(2) Canarese;

(3) Hathinentu Manayavaru (eighteen house people);

(4) Sivachara;

(5) Ariya;

(6) Kodekal Hatakararu (weavers). They are practically divided into two linguistic sections, Canarese and Telugu, of which the former have adopted the Brāhmanical ceremonials to a greater extent than the latter, who are more conservative. Those who wear the sacred thread seem to preponderate over the non-thread weavers in the Canarese section. To the thread is sometimes attached metal charm-cylinder to ward off evil spirits.

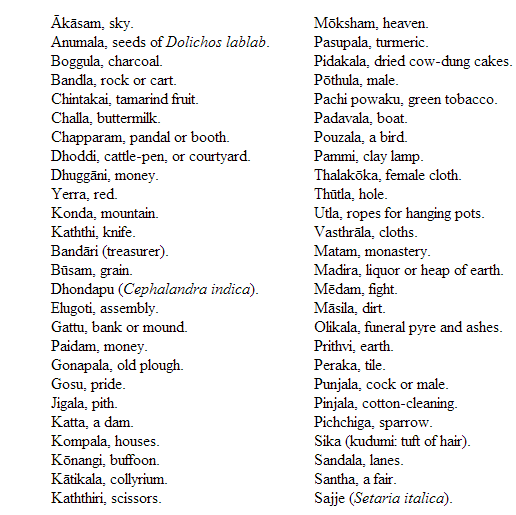

The following are examples of exogamous septs in the Telugu section:—

The majority of Dēvāngas are Saivites, and wear the lingam. They do not, however, wash the stone lingam with water, in which the feet of Jangams have been washed. They are not particular as to always keeping the lingam on the body, and give as an explanation that, when they are at work, they have to touch all kinds of people. Some said that merchants, when engaged in their business, should not wear the lingam, especially if made of spatikam (quartz), as they have to tell untruths as regards the value and quality of their goods, and ruin would follow if these were told while the lingam was on the body.

In some parts of Ganjam, the country folk keep a large number of Brāhmini bulls. When one of these animals dies, very elaborate funeral ceremonies take place, and the dead beast is carried in procession by Dēvāngas, and buried by them. As the Dēvāngas are Lingāyats, they have a special reverence for Basavanna, the sacred bull, and the burying of the Brāhmini bull is regarded by them as a sacred and meritorious act. Other castes do not regard it as such, though they often set free sacred cows or calves.

Dēvāngas and Padma Sālēs never live in the same street, and do not draw water from the same well. This is probably due to the fact that they belong to the left and right-hand factions respectively, and no love is lost between them. Like other left-hand castes, Dēvāngas have their own dancing-girls, called Jāthi-biddalu (children of the castes), whose male offspring do achchupani, printing-work on cloth, and occasionally go about begging from Dēvāngas. In the Madras Census Report, 1901, it is stated that “in Madura and Tinnevelly, the Dēvāngas, or Sēdans, consider themselves a shade superior to the Brāhmans, and never do namaskāram (obeisance or salutation) to them, or employ them as priests. In Madura and Coimbatore, the Sēdans have their own dancing-girls, who are called Dēvānga or Sēda Dāsis in the former, and Mānikkāttāl in the latter, and are strictly reserved for members of the caste under pain of excommunication or heavy fine.”

Concerning the origin of the Dēvānga beggars, called Singamvādu, the following legend is current. When Chaudēswari and Dēvālan were engaged in combat with the Asuras, one of the Asuras hid himself behind the ear of the lion, on which the goddess was seated. When the fight was over, he came out, and asked for pardon. The goddess took pity on him, and ordered that his descendants should be called Singamvāllu, and asked Dēvālan to treat them as servants, and support them. Dēvāngas give money to these beggars, who have the privilege of locking the door, and carrying away the food, when the castemen take their meals. In assemblies of Dēvāngas, the hand of the beggar serves a spittoon. He conveys the news of death, and has as the insignia of office a horn, called thuththari or singam.

The office of headman, or Pattagar, is hereditary, and he is assisted by an official called Sesha-rāju or Umidisetti who is the servant of the community, and receives a small fee annually for each loom within his beat. Widow remarriage is permitted in some places, and forbidden in others. There may be intermarriage between the flesh-eating and vegetarian sections. But a girl who belongs to a flesh-eating family, and marries into a vegetarian family, must abstain from meat, and may not touch any vessel or food in her husband’s family till she has reached puberty. Before settling the marriage of a girl, some village goddess, or Chaudēswari, is consulted, and the omens are watched. A lizard chirping on the right is a good omen, and on the left bad. Sometimes, red and white flowers, wrapped up in green leaves, are thrown in front of the idol, and the omen considered good or bad according to the flower which a boy or girl picks up.

At the marriage ceremony which commences with distribution of pān-supāri (betel) and Vignēswara worship, the bride is presented with a new cloth, and sits on a three-legged stool or cloth-roller (dhonige). The maternal uncle puts round her neck a bondhu (strings of unbleached cotton) dipped in turmeric. The ceremonies are carried out according to the Purānic ritual, except by those who consider themselves to be Dēvānga Brāhmans. On the first day the milk post is set up being made of Odina Wodier in the Tamil, and Mimusops hexandra in the Telugu country. Various rites are performed, which include tonsure, upanāyanam (wearing the sacred thread), pādapūja (washing the feet), Kāsiyātra (mock pilgrimage to Benares), dhārādhattam giving away the bride), and māngalyadhāranam (tying the marriage badge, or bottu).

The proceedings conclude with pot searching. A pap-bowl and ring are put into a pot. If the bride picks out the bowl, her first-born will be a girl, and if the bridegroom gets hold of the ring, it will be a boy. On the fifth day, a square design is made on the floor with coloured rice grains. Between the contracting couple and the square a row of lights is placed. Four pots are set, one at each corner of the square, and eight pots arranged along each side thereof. On the square itself, two pots representing Siva and Uma, are placed, with a row of seedling pots near them. A thread is wound nine times round the pots representing the god and goddess, and tied above to the pandal. After the pots have been worshipped, the thread is cut, and worn, with the sacred thread, for three months. This ceremony is called Nāgavali. When a girl reaches puberty, a twig of Alangium Lamarckii is placed in the menstrual hut to keep off devils. The dead are generally buried in a sitting posture. Before the grave is filled in, a string is tied to the kudumi (hair knot) of the corpse, and, by its means, the head is brought near the surface. Over it a lingam is set up, and worshipped daily throughout the death ceremonies.

The following curious custom is described by Mr. C. Hayavadana Rao. Once in twelve years, a Dēvānga leaves his home, and joins the Padma Sālēs. He begs from them, saying that he is the son of their caste, and as such entitled to be supported by them. If alms are not forthcoming, he enters the house, and carries off whatever he may be able to pick up. Sometimes, if he can get nothing else, he has been known to seize a [165]lighted cigar in the mouth of a Sālē, and run off with it. The origin of this custom is not certain, but it has been suggested that the Dēvāngas and Sālēs were originally one caste, and that the former separated from the latter when they became Lingāyats. A Dēvānga only becomes a Chinērigādu when he is advanced in years, and will eat the remnants of food left by Padma Sālēs on their plates. A Chinērigādu is, on his death, buried by the Sālēs.

Many of the Dēvāngas are short of stature, light skinned, with sharp-cut features, light-brown iris, and delicate tapering fingers. Those at Hospet, in the Bellary district, carried thorn tweezers (for removing thorns of Acacia arabica from the feet), tooth-pick and ear-scoop, suspended as a chatelaine from the loin-string. The more well-to-do had these articles made of silver, with the addition of a silver saw for paring the nails and cutting cheroots. The name Pampanna, which some of them bore, is connected with the nymph Pampa, who resides at Hampi, and asked Paramēswara to become her husband. He accordingly assumed the name of Pampāpathi, in whose honour there is a tank at Anagūndi, and temple at Hampi. He directed Pampa to live in a pond, and pass by the name of Pampasarovara.

The Sēdans of Coimbatore, at the time of my visit in October, were hard at work making clothes for the Dīpāvali festival. It is at times of festivals and marriages, in years of prosperity among the people, that the weavers reap their richest harvest.

In the Madras Census Report, 1901, Bilimagga (white loom) and Atagāra (weavers and exorcists) are returned as sub-castes of Dēvānga. The usual title of the Dēvāngas is Chetti.

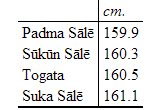

The shortness of stature of some of the weaving classes which I have examined is brought out by the following average measurements:—