Dhoba, Bengal

Contents[hide] |

Dhoba

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Origin

The washerman: caste of Bengal and Orissa, who claim desoent From Neta Muni or Netu Dhopani, who washed the clothes of Brahma. According to another story, Neta was the son of a devotee called Dhohi Muni, who washed his loin cloth (kopin) in a river, and thereby so fatigued himself that he oould not fetoh flowers for the daily worship. For this neglect his fellow-devotees oursed him, and he and his posterity were condemned to follow the profession of washing dirty clothes. The Skanda Purana quoted in the Jati Kaumudi makes the Dhobas the offspring of a Dhibar rather and a Tibar mother-a statement quite unsupported by evidence, whioh is only mentioned here in illustration of the oommon tendenoy to insist on referring every caste now existing to some mode of mixed parentage.

Internal structure

Owing to the tmiversal custom whioh forbids a Hindu to wash his own clothes, the Dhobi caste is very widely distributed, and has in Bengal Prpoer been broken up into an unusually large number of sub•castes. Eighteen of these are shown in Appendix I, but I am by no means certain that the enumeration is exhaustive. In Eastern Bengal two great divisions are recognised-Ramer Dhoba and Sitar Dhoba ; the former claiming descent from the washermen of Rama, and the latter from those of Sita. Members of these two groups eat and drink together, but never intermarry. The story is that originally Rama's washermen worked only for men, and Sita's only for women. The latter received a special payment of nine pans (720) of golden cowries for washing Sita's menstrual cloths, and this made Hama's washermen covetous, so that one day they stole those garments and washed them themselves. From that time it is said each branch of the caste took to washing indifferently for either sex. In Central Bengal we find four sub•castes-Satisa. Athisa, Haj ara Samaj, and Nitisina. The first two are said to have reference to the number of families originally comprised in each group '; the third is suppo ed to consist of a thousand persons degraded for some breach of social rules ; the fourth are day-labourers as well as washer¬ men. The distinctions between the first three are said to be less strictly maintained of late years. The Hughli Dhobas have four sub¬ castes-Bara Samaj, Chhota Samaj, Dhoba Samaj, and Rarhiya Samaj, the members of which do not intermarry and cannot eat cooked rice together. In Noakhali we find three endogamous groups bearing the names of parganas Bhulua. Jugidia, and Sundip. In Orissa there appear to be no suh-castes. The Manbhum smies, Bangali, Goria, Maghaya, and Khotta, seems at first sight akin to the Behar set of sub-castes, in that it recognises Bangali and Maghaya as distinct geographical groups. I have, however, placed the Manbbum Dhobas in the Bengal division of the ca te, because they speak Bcngali themselves and are on the whole more subject to Bengal than to Behar influences. The sections of the Bengal Dhobas present no points of special interest. All of them have been borrowed from the Brahmanical system, and are not taken into account in arranging marriages. there is, indeed, usually only one gotra current in each local com¬ munity, and that seems to be retained mainly from the force of custom and as a badge of social distinction. The prohibited degrees are the same as in other castes of about the same position in sooiety.

Marriage in Bengal

Bengal Dhobas, inoluding the Manbhum members of the caste, marry their daughters as infants, at the age nrnngo m Bengal. of from seven to nine years. Boys are usually married between eleven and fifteen, but the sons of poor men, who cannot afford to pay the bride-price (pan) , often remain unmarried till five-and-twenty, by which time a man has probably earned enough to secure a wife for himself. The marriage ceremony is the ame as is observed by most of the lower castes. The carrying of the bride seven times round the bridegroom is regarded as its binding portion. Polygamy is fully recognised in the case of well-to-do men whose first wives are barren; for others it is allowed, but is not considered quite respectable. Widows may not marry a second time. Divorce is not allowed, but when a husband casts off his wife for adultery a reference is usually made to the panchayat and a purificatory ceremony (prayascltitta) , such as is described in the article on Cbasadhoba, is gone through by the husband. Women thus cast off cannot marry again. Among the Dhobas of Eastern Bcngal some curious usages prevail in respect of marriage. Every samlij or local assemblage of the Ramer-Dhoba sub-caste is headed by three officials, known in order of rank as the Naik, the Paramanik, and the Barik. The rest of the assemblage or community are known by the general name Samajik. For marriages between equals, that is between persons both of whom belong to the same class, whether official or Samajik, the bride-price is fixed at Rs. 50. But where the parties do not belong to the same class, the bride-price varies above or below this sum in relation to the rank of the bride and bridpgroom. Thus a Samajik marrying the daughter of a Barik, Pariimanik, or N1iik will pay Rs. 51, Rs. 52, or Rs. 53, as the case may be; while a Naik marrying in the classes below him pays Rs.49, Rs. 48, or Rs. 47, according to the rank of the bride. A somewhat less elaborate system exists in the Sitar-Dhoba sub-caste. There the headman of the Samaj is called Pradhan, and the second Paramanik, but there is no third official The amount of pan varics with tho rank of the bride, but neither the Dormal amount DOl' the scale of variation is fixed by custom. In Murshedabad and other districts of Central Bengal the Samaj of the Dhoba caste is presided over by threc officials-Para-manik, Barik, and Mandai, who are consulted whcn a marriage is under consideration, and who decide any questions regardiug affinity which may arise.

Marriage and structure in Orissa

The Dhobas of Orissa differ in several important particulars from the Dhobas of Bengal. In the first place they have among their gotras the distinctly totemistic group Nagasa, the members of which revere the snake as their common progenitor, and observe the primitive rule of exogamy, which forbids a man to marry a woman who bears the same totem as himself. Prohibited degrees of course are recognised, but the form in which they are stated shows them to be later amplifications of a more archaic method of preventing marriages between persons of near kin.

Again, adult as well as infant-marriages are sanctioned, and there are no limits to polygamy. A man may take as many wives as he likes or can afford to maintain. Widows may marry again under much the same conditions as are recognised by the non-Aryan races of Chota Nagpur. The ritual observed is sanga. When such a marriage is under consideration, the widow appears before a caste council and solemnly cuts an areca nut (supari) into two pieces. This is supposed to symbolize ber complete severance from the family of her late husband. 'rbe actual ceremony gone through on the day of the sango, is of the simplest character. The bridegroom decks the bride with new ornaments, denoting that she has put off the unadorned state of widowhood, and a feast is given to the members of the caste, their presence at which is deemed to ratify the marriage. While permitting widows to remarry, the Orissa Dhobas do not extend this pri vilege to divorced women. In dealing with women taken in adultery, the main point is whether the paramour is a member of the caste or not. If he is, I gather that the moral sense of the community is satisfied by the imposition of some slight penance, and that the husband by no means invariably insists on getting rid of his wife. A liaison with an outsider, however, admits of no atonement, and the offending woman is simply turned out of the caste.

Religion

The Religion of the Dhoba caste, whether in Bengal or in Orissa, exhibits no points of special interest. Most Religion. Dhobas belong to the Vaishnava sect, and a few only are Saktas. Like many other serving castes, they pay especial reverence to Viswakarma. They employ Brahmans for religious and ceremonial purposes, but the Dhoba Brahman, as he is usually called, ranks very low, and is looked down upon by those members of the priestly order who serve the higher castes. In the disposal of the dead and the subsequent propitiatory ceremonies they follow the standard customs of lower class Hindus. It deserves notice that the Dhobas of Orissa bury children up to five years of age face downwards-a practice which in Upper India is confined to members of the sweeper caste.

Occupation

The necessities of Hindu society give rise to a very steady demand for the services of the Dhoba, and for this reason a comparatively small proportion of the caste bave abandoned their distinctive occupation in favour of agriculture. The village Dhobi, however, besides receiving customary presents at all village festivals, often bolds c/uikaran land in recognition of the services rendered by him to the community. In Eastern Bengal, according to Dr. Wise, the presence of the Dhoba is deemed indispensable at the marriages of the higher classes, as on the bridal morn be sprinkles the bride and bridegroom with water colleoted in the palms of his bands from the grooves of his washing-board (pat), and aftedhe bride has been daubed with turmeric the Dhoba must touch her to signify that she is purified. In Daccaa, says the same accurate observer, the washerman is hard-working, regular in his hours of labour, and generally one of the first workmen seen in the early morning, making use of a small native bullock, as the donkey does not thrive in Bengal, for carrying his bundles of clothes to the outskirts of the town. He cannot, however, be said to be a careful washerman, as he treats fine and coarse garments with equal roughness j but for generations the Dacca Dhobas have been famous for their skill, when they choose to exert it, and early in this century it was no uncommon thing for native gentlemen to forward valued articles of apparel from Calcutta to be washed and restored by them. At the present day Dhobas from Kochh Behar and other distant places are sometimes sent while young to learn the trade at Dacca.

Mode of washing

For washing muslins and other cotton garments, well or spring water is alone used ; but if the articles are the property of poor man, or are commonplace, the water of the nearest tank or river is accounted sufficiently good.

The following is their mode of washing. The cloth is first cleansed

with soap or fuller's earth, then steamed, steeped in earthen vessels

filled with soap suds, beaten on a board, and finally rinsed in cold

water. Indigo is in as general use as in England for removing the

yellowish tinge and whitening the material. The water of the wells

and springs bordering on the red laterite formation met with on the

north of the city has been for centuries celebrated, and the old

bleaching fields of the European factories were all situated in this

neighbourhood. Dhobas use rice starch before ironing and folding

clothes, for which reason no Brahman can perform rus devotions or

enter a temple without first of all rinsing in water the garment he

has got back from the washerman.

Various plants are used by Dhobas to clarify water, such as

the nir-mau (Strychnos potatorum) pui (Basella), nagphanl (Cactus

Indicus), and several plants of the mallow family. Alum, though

not much valued, is sometimes used.

The Dhoba often gives up his caste trade and follows the

profession of a writer, messenger, or collector of rent (tahsildar).' and

it is an old native traditlon that a Bengali Dhoba was the first Inter

preter the English factory of Calcutta bad, while it is further stated

that our early commercial transactions were solely carried on through

the agency of low-caste native. The Dhoba, however, will never engage

himself as an Indoor servant ill the house of a European.

Among the natives of Bengal the washerman, like the barber,

is proverbially considered untrustworthy, and when the former says . the clothes are almost ready he is not to he believed. The Bengali Dhoba is not so dissipated as his Hindustani namesake, whose drinking propensities are notorious, but he is said to indulge frequently in

ganja-smoking.

Social status

The Dhoba is reckoned as unclean because he washes the puerperal garments-an occupation which, according to Hindu ideas, is reserved for outcaste and abandoned races. His social rank therefore is low, and we find him classed with Chandils, Jugis, Mals, and the like. Notwithstanding this he assumes many airs, and lays down a fanciful standard of rank to suit his pleasure. Thus in Bikrampur, in Dacca, he declines to wash for the Patuni, Rishi, Bhuinmali, and Chandal, but works for the Sunri, because the Napit does so, and for all classes of fisher¬men. Be also refuses to attend at the marriages of any Hindus but those belonging to the Nava•Sakha, and under on circumstances will he wash the clothes worn at funeral ceremonies.

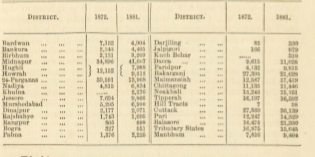

The following statement shows the number and distribution of Dhobas in Bengal, Orissa, and Manbhum in 1872 and 1881 :¬