Dom

Contents[hide] |

Dom

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Traditions of origin

Domra sometimes called Chandal by outsiders, a Dravidian menial caste of Bengal, Behar, and the North-Western Provinces, regarding whose origin much has been said. Dr. Caldwell 1 considers the" Dams and other Chandalas of Northern India and the Pareiyas and other low tribes of the Peninsula" to be the surviving representatives of an older, ruder, and blacker race, who preceded the Dravidians in India. Some of these were driven by the Dravidian invasion to take refuge in mountain fastnesses and pestilential jungles, while others were reduced to perpetual servitude like the Dams of Kumaon, whom Mr. Atkinson' describes as for ages the slaves of the Khasiyasthought less of than the cattle, and, like them, changing hands from master to master. Sir Henry Elliot 3 says they "seem to be one of the aboriginal tribes of India. Tradition fixes their residence to the north of the Gogra, touching the Bhars on the east, in the vicinity of Rohini. Several old forts testify to their former importance, and still retain the names of their founders; as, for instance, Domdiha and Domanr,arh. 4 Ramgarh and Sahankot on the Rohini are also Dam forts." Mr. Carnegy5 observes that the fort of Domangarh was the stronghold of the Damar, a degenerate clan of Rajputs, and suggests in a note that these Damar or Donwar may them elves have been a family of Doms who had risen to power locally and got themselves enrelled in "the conveniently elastic fraternity of Rajputs." In support of this theory he refers to the case of Ali Balesh Dam, who became Governor of Ramlabad, one of the districts of Oudh, and mentions that it was not uncommon for men of this class to rise to high office under kings by whom they were employed as musicians. 1 Gramma1' of tlte Dravidian Languages, p. 546. 2 North-Western Provinces Gazetteer, vol. xi, p. 370. 3 Races of tlte North-Western Provincps, i, 84. 4 Buchanan, Eastern India, ii, p. 353, calls this the "Domingar or the castle of the Dom lady." It should be noted that Sir Henry Elliot misunder¬stands Buchanan, who nowhere gives it as his own opinion that the Doms are the same as the Domkatar section of the Babhan caste, though he mentions (ii, 471) without comment a popular tradition to that effect. 5 Notes Oil tlte Races of Avadlt (Oudlt), p. 24 Out of this somewhat profitless discussion there seems to emerge a general consensus of opinion that the Doms belong to one of the races whom, for convenience of expression, we may call the aborigines of India.

Their personal appearance bears out this opinion. Mr. Beames describes the Magahiya Doms of Ohamparan as "small and dark, with long tresses of unkempt hair,and the peculiar glassy eye of the non-Aryan autochthon j" J and Mr. Sherring remarks that" dark¬complexioned, low of stature, and somewhat repulsive in appearance, they are readily distinguishable from all the better castes of Hindus." 2 The type, however, as is the case with most widely-diffused castes, seems to display appreciable variations. In Eastern Bengal, according to Dr. Wise, the Dom's hair is long, blaok, and coarse, while his complexion is oftener of a brown rather than a black hue j and among the Magahiya Doms whom I have seen in Behar only a small proportion struck me as showing any marked resemblances to the aborigines of Chota Nagpur, who are, I suppose, among the purest specimens of the non-Aryan races of India. On the whole, however, the prevalent type of physique and complexio~ seems to mark the caste as not of Aryan descent, although evidence is wanting to counect it with any compact aboriginal tribe of the present day. The fact that for centuries past they have been condemned to the most menial duties, and have served as the helots of the entire IIindu community, would of itself be sufficient to break down what¬ever tribal spirit they may once have possessed, and to obliterate all structural traces of their true origin.

Internal structure: endogamy

The Dom community is a large one, and the intrioacy of its internal organization is doubtless due for the most part to the large area over which the caste is distributed. The sub-castes and sections are given in a tabular form in Appendix I. About most of these there is very little to be said. Enquiry into the origin of sub-castes is usually a difficult and unfruitful process, and it is attended with peculiar difficulties in the case of a caste regarded by all Hindus with extreme repulsion, and destitute of the social pride which delights to recall the reasons for minute internal divisions. The Maga¬hiya Doms of Behar have a legend that once upon a time Mahadeva and Parvati invited all the castes to a feast. Supat Bhakat, the ancestor of the Doms, cnme late, and being very hungry, mixed up and ate the food which the others had left. His behaviour was deemed so scandalous that he and his descendants were straightway degraded and condemned to eat the leavings of all other castes. Even at the present day if a Dom wbo comes to beg i asked to what caste ho belongs, the answer will invariably be " Jhuta-khai," or eater of leavings. This myth is uuknown to the Doms of Central and W estern Bengal, who trace their origin to a common ancestor called Kalubir, the son of a Ohandal woman by her Let3 husband. From his four sons, Pranbir, Manbir, Bhanbir, and SMnbir, the sub-castes A:nkuria, Bisdelia, Bajunia, and Magahiya ru:e said to

1 Races of the N01•tll-Western Provinces, p. 85. 2 2 Hind1t l."ribcs alld Castes, i, 40l. 3 3 Let is a sub-caste of the £agdis in Murshcdabad. be desoended, The two elder sons, Pranbir and Manbir, wero, it is said, sent out to gather flowers for a sacrifice. Pranbir, who wa s lazily inolined, tore the flowers from the trees with a bamboo hook (dnkuli) and picked them up as they fell on the ground ; while Man bir olim bed the trees and gathered flowers carefully from branch to branch. '}'he flowers brought in by Manbir were acceptAd, and he'received the title of Bisdelia (his, 'twenty,' and elat, ' a branch '), because he had climbed twenty branches in the service of the gods. The elder brother's oHering was rejected as unclean, and he and his descendants were named Xnkuritt in reference to the hook. On hearing this decision the third brothel' was greatly pleased, and drummed on his stomach in token of satisfactiou. He and his offspring therefore were entitled Bajnnia, or musician Doms. The Dhabl1 Dhesia or Tapaspuria Doms, who remove dead bodies and dig the cross trench w bich forms the base of the funeral pyre, also claim descent from Kalubir. On e of his sons, they say, was sent by ¥ahadeva to fetch water from the Ganges. At the river bank he found a dead body waiting to be burned, and was tempted by oHers of money from the' friellds of the deceased to dig the nece~sary trench. On his return to MaMdeva the god cursed him and his descendants to minister to the dead for all time. No special legend is given to account for the name Magahiya, which doubtle~s originally denoted the Doms of South Behar. The Dai sub-caste owe their pame to the circumstance that their women act as midwives in parts of the country where Chamains are not numerous enough to perform this function. The men are day-labourers. The BanSl hor or bamboo-splitter' sub-caste derive their name from Ithe material out of which they make baskets j while the Uhapariya seem to be so called from building the bamboo frame-work by which a roof (chapar)is supported. The Uttariya Doms of South Behar work in sirki, and regard this as an important distinction between themselves and the Magahiya, who in that part of the country till the soil and make mats and baskets of bamboo.

Internal structure: exogamy

The exogamous sections of the caste are very numerous. In Behar they seem to be territorial or titubar while in Bankura the names are totemistic, and the members of particular sections refrain from :injuring the animals after which they are called. In Central Bengal traces of totem:ism may perhaps be found, but the tendency is to borrow the Brahmanical gotras, while in the eastern districts all exogamous groups seem to have disappeared, and marriages are :regulated by the more modern system of counting prohibited degrees down to and including the fifth generation in descent from a common ancestor. The Magahiya Dams of Behar afIect to observe a very elaborate method of working the rule of exogamy. They lay down that a man may not marry a woman belonging to the same section as his own (1) father, (2) paternal grandmother, (3) paternal great-grandmothers, (4) paternal great-great-grand-mother~, (5) mother, (6) maternal grandmother, (7) maternal great¬grandmothers. In applying the rule to a particular case, all the sections on both sides a~'e taken into at in account manner described in the article on Bais, so that a marriage would be barred if one of the great-grandmothers of the proposed bride happened to have belonged to the same section as one of the great-great-grand-mothers of the proposed bridegroom, even though the parties them¬selves belonged to dillerent rn!~ls. This mode of caloulation appears to be oonfined to Behar; and in Bengal wherever eotions exist, the only rule observed is that a man may not marry a woman of the samo section a himself. The standard formula for reckoning prohibited degrees is in general use. In Bankura it is ordinarily calculated to three generations in the descending line; but where bltaitidi, or mutual recognition of relationship, has been kept up between two families, the prohibition extends to five generations. The Doms of the 24-Parganas affect to prohibit marriage i>.3tween sapindas, but this is a palpable imitation of the customs of the higher castes.

Members of other castes may be received into the Dom community by paying a fee to the panchayatu.nd giving a feast to the Doms of the neighbourhood. At this feast the proselyte is required to wait upon his new associates and to eat with them. TIe must also have his hp,ad shaved and undergo a sort of baptism with water at the hands or the caste pancbayat in token of his adoption of the Dom Religion. Instances of mon of other castes thus joining themselves to the Doms are very rare, and ocour only when a man has been ejected from his own caste for living with a Dom woman. Some say, however, that iJ,l these cases the proselyte, though ordinarily spoken of as a Dom, is not admitted to completo equality with the original members of the caste. His ohildren, however, will be Doms of the same sub-caste-as their mother_

Marriage

In Central and Eastern Bengal Doms, following the example the higher castes, nearly always marry their daughter as infant, and regard it as wrong for a girl over ten years of age to remain unmarried in her father house . A smallbride price (pan), Varying from Rs5 to Rs. 10, is paid to the parents of the girl. In Behar and Western Bengal adult-marriage still holds its ground for those who oannot afford the more tashionable praotice, and sexual intercourse before marriage is said to be tolerated. Among the Doms of the Dacca district the marriage servioe is peouliar. Tho guests being assembled on a propitions day fixed by a Brahman, the bridegroom's father takes his son on his knee, aud, sitting down in the centro of the" Marooha " opposite the bride's father, who is holding his daughter in a similar posture, repeats the names of his ancestors for sevon generations,. while the bride's father runs over his for three. They then call God to witness the oeremony, and the bridegroom's father addressing the other asks him, "ITave you lost your daughter?" The answer being in the affirmative, a similar interrogation and reply from the opposite party terminates the service. The boy-bridegroom then advances, smears the bride's forehead with silldul' or red lead-the symbol of married life-tal,es her upon his knee, and finally carries her within doors. Like all aborigiual races, Doms are very fond of gaudy colours; the bridal dre s oonsisting of yellow or red garments for tho female, and a yollow oloth with a reel turban for the male.

In the 24-Parganas a more Hinduised ritual is in vogue. The marriage takes place on a raised earthen platform (becli), to which a branch of a banian-tree is fixed. An earthen vessel full of Ganges water is placed in the centre. On this vessel the bride and bride-groom lay their hands, one above the other, and the ceremony is completed by exchanging garlands of flowers. The Dom priest, Dharma-Pandit, presides and mutters words which purport to be sacred texts, and the actual marriage service is preceded by offerings to ancestors and the worship of Surya, Ganesa, Dmga, Mahadeva, and Anti-Kuldevata. Fmther west again, in the districts of Bankura and Manbhum, the ritual appears to differ little from that already described in the article on the Bagdi caste. There is, how¬ever, no marriage with a tree and no symbolic capture of the bride, as in the case of the Bagdis; while in the joining of the hands which precedes sindurdtin, the bride presents her right hand if she is given away by -a male, and her left if by a female relative. On the 11ight before the wedding the ceremony of adhibtis is performed in the houses of both parties by anointing the body with tmmeric and oil and tying a thread soaked in this mixture and knotted with a few blades of durva grass on the right wrist of the bridegroom and the left wrist of the bride. the ritual followed in Behar is of the simplest character, consisting mainly of Sindurdan, which is often performed in the open air under a tree. the wealtbier Doms, however, erect a wedding canopy (marwa) , and generally copy the Hindu ceremony with more or less acomacy of detail.

Polygamy is everywhere permitted, and poverty forms the only restriction on the number of wives a man may have. The standard of living however is low, and it is unusual to find a Dom with more than two wives, and most men content themselves with one. A widow may marry again, and in Behar it is deemed right for her to marry her late husbaud's younger brother; but in Bengal this idea does not seem to prevail, and a widow may marry anyone she pleases provided that she does not infringe the prohibited degrees binding on her before her first marriage. the ritual (sanga or sagai) observed at the marriage of a widow consists mainly of sinclltl'dan and the present of a new cloth. A pan is rarely paid, and never exoeeds a rupee or two. In Mmshedabad there is no sindu1'dan, and a formal declaration of consent before representatives of the caste is all that is required. Considerable license of divorce is admitted, and in some districts at any rate the right can be exeroised by either husband or wife; so that a 'Woman, by divesting herself of the iron bracelet given to her at marriage, can rid herself of a husband who ill-treats her or is too poor to maintain her properly. Dom women have a reputation for being rather masterful, and many of them are conspicuous for their powerful physique. It may be by virtue of their characteristics that they have established a right very rarely conceded to women in Bengal. A husband, on the other hand, can divorce his wife for infidelity or persistent ill-temper. In either case the action of the individual requires the confirmation of the panchftyat, which however is usually given as a matter of course, and is expressed in BMgalpur by solomnly pronouncing the pithy monosyllable Jao. In North Bhagalpur the husband takes in his hand a bundle of rice straw and outs it in half before the assemblage as a symbol of separation. Divorced wives may marry again by the same ritual as widows. Their ohildren remain in the charge of their first husband. In Monghyr the second husband must give the panchayat a pig to form the basis of a feast, and if convicted of having seduoed the woman away from her first husband must pay the latter Rs. 9 as compensation. A husband, again, who divorces his wife has to pay a fee of 10 annas to the pancMyat for their trouble in deciding the case.

Most of the sub-castes seem to have a fairly complete organiza¬tion for deciding sooial questions. The system of panchayats is every¬where in full force, and in Behar these are presided over by here¬ditary headmen, variously called sarda?', prudhan, manjhan, marar gorait or kabiraj, eaoh of whom bears rule in a definite local juris¬diotion, and has under him a chharidar' or rod-bearer to call together the panchayat and to see that its orders are carried out.

Religion

The Religion of the Doms varies greatly in different parts of the country, and may be desoribed generally as a. chaotio mixture of survivals from the elemental or animistio cults oharaoteristic of the aboriginal raoes, and of observances borrowed in a haphazard fashion from whatever Hindu Bect happens to be dominant in a partioular looality. The oomposite and ohaotio nature of their belief is due partly to the great ignorance of the caste, but mainly to the fact that as a rule they have no Brahmans, and thus are without any central authority or standard which would tend to mould their religious usages into conformity with a uniform standard. In Behar, for instanoe, the son of a deceased man's sister or of his female oousin officiates as priest at his fuueral and reoites appropriate mantras, receiving• a fee for his services when the inheritance oomes to be divided. Some Doms, indeed, assured me that the sister's son used fOlmerly to get a share of the property, and that this rule had only recently fallen into disuse; but their statements did not seem to be definite enough to oarry entil:e oonviotion, and I have met with no oorroborative evidence bearing on the point. So also in marriage the sister's son, or oocasionally the sister (saw£lsin), repeats mant?"a8, and aots generally as priest. Failing either of these, the head of the household offioiates.

The possible significanoe of these faots in relation to the early history of the caste need not be elaborated here. No other indioa¬ tions of an extinot oustom of female kinship are now traceable, and the faot that in Western Bengal the eldest son gets an extra share (ieth-angs) on the division of an inheritance seems to show that kinship by males must have been in force for a very long time past. In Bengal the sister's son exercises no priestly functions, these being usually discharged by a special olass of Dom, known in Bankura as Degharia, and in other districts as Dharma-Pandit. Their office is hereditary, and they wear oopper rings on their fingers as a mark of distinotion. In Murshedabad, on the other hand, most Doms, with the exoeption of the Banukia sub-caste and some of the Ankurias, have the services of low Brahmans, who may perhaps be ranked as Barna-Brahmans. The same state of things appears to prevail in the north of Manbhum. In the Santitl Parganas barbers minister to the spiritual wants of the caste.

In Bengal

With suoh a motley array of amateur and professional priests, it is clearly out of the question to look for nenga. any unity of religious organization among the Doms. In Bankura and Western Bengal generally they seem on he whole to lean towards Vaishnavism, but in addition to Radha and Krishua they worship Dharam Raj' Dharma-raj in form of a man with a fish's tail on the last day of Jaishtha with offerings of rioe, molasses, plantain, and sugar, the object of which is said to be to obtain the blessing of the sun on the orops of the season. Every year in the month of Baisakh the members of the caste go into the jungle to offer saorifioes of goats, fruits, and sweetmeats to their anoestral deity Kalubu:; and at tho appointed season they join in the worship of the goddess Bhadu, desoribed in the article on the Bagdi caste. At the tilne of the Durga Puja, Bajunia Doms worship the dmm, which they regard as the symbol of their oraft. This usage has clearly been borrowed from the artisan castes ari:lOng the Hindus. In Central Bengal Kali appears to be their favourite goddess; and in Eastern Bengal many Doms follow the Pantlz, or path of Supat, Supan, or Sobhana Bhagat, who is there regarded as a guru rather than as the progenitor of the caste. Others, again, call themselves Haris Chandls, from Raja Haris Chandra, who was so generous that he gave away all his wealth in oharity, and was reduoed to suoh straits that he took service with a Dom, who treated him kindly. In return the Raja converted the whole tribe to his Religion, which they have faitbfully followed ever since. 1

The principal festival of the Doms in Eastern Bengal is the Sravannia Puja, observed in the month of that name, corresponding to July and August, when a pig is saorificed and its blood oaught in a cup. This cup of blood, along with one of milk and three of spirits, are offered to Narayan. Again, on a dark night of Bbadra (August) they offer a. pot of milk, four of spirits, a fresh cocoanut, a pipe of tobaoco, and a little Indian hemp to Hart Ram, after which swine are slaughtered and a feast oelebrated. A ourious custom followed by all castes throughout Bengal is assooiated with

1 This is the form of the legend current among the Doms of Dacca. It will be observed that the Chand{ua of the Markandeya .Purana has been turned into a Dom, and the pious kio.g into a religious reformer. According to Dr. Wise, Haris Chandra is a well• known figure in the popular mythology of :Bengal, and it is of him that natives tell the following story, strangely like that narrated in the xviiith chapter of the Koran regarding Moscs and Joshua. He and his Rani, wandering in the forest, almost starvcd, caught a fish and boiled it on a wood fire. She took it to the river to wash off the ashes, but on touchin~ the water the fish revived and swam away. At the present day a fish called kalbo a (Labeo calbasu), of black colour and yellow flesh, is identified with the historical one, and no low-caste Hindu will touch it. In Hindustan the following couplct is quoted concerning a similar disaster which befell the gambler N ala, the moral being the samc as Lhat of the English proverb-" Misfortunes nevcr come singly" ;¬

"Raja Nal par bihat pare, Bhu.ne machhle jal men tire." the Dom, and may perhaps be a survival from times when that cnste were the recognised priests of the elemental deities worshipped by the non-Aryan races. Whenever an eclipse of the sun Or moon occurs, every Hindu householder places at his door a few copper coins, which, though now olaimed by the Roharji Brahman, were until reoently regarded as the exclusive perquisite of the Dam.

In Behar

Similar confusion prevails in Behar under the regime of the sister's son, only with this difference, that the advance in the direction of Hinduism seems to be on the whole less conspiouous than in Bengal. Mahadeva, Kali, and the river Ganges receive, it is true, sparing and infrequent homage, but the working deities of the caste are Syam Singh, whom some hold to be the deified anoestor of all Dams, Rakat Mala, Gbihal or Gohil, Goraiya, Bandi, Lakeswar, Dihwar, Dak, and other ill-defined and primitive shapes, which have not yet gained admis¬sion into the orthodox pantheon. A.t Deodha, in Darbhanga, Syam Singh has been honoured with a special temple; but usually both he and the other gods mentioned above are represented by lumps of dried clay, set up in a round space smeared with cow-dung. inside the house, under a tree or at the village boundary. Before these lumps, formless as the oreed of the worshipper who has moulded them, pigs are saorificed and shang drink offered up at festivals, marriages, and when disease threatens the family or its live-stock. The circle of these godlings, as Mr. Ibbetson has excellently called them, is by no means all exclusive one, and a common custom showR how simply and readily their number may be added to. If a man dies of snake-bite, say the Magahiya. Dams of the Gya district, we worship his spirit as a Sampm•i.l/a, lest he should come back and give us bad dreams, we also worship the snake who bit him, lest the snake•god should serve us in like fashion. Any man therefore conspicuous enough by his doings in life or for the manner of his death to stand a chance of being dreamed of among a tolerably large circle is likely in course of time to take rank as a god.

Judging, indeed, from the antecedents of the caste, Syam Singh himself may well have been nothing more than a successful dacoit, whose career on earth ended in some sudden or tragic fashion, and who lived in the dreams aT his brethren long enough to gain a place in their rather disreputable pantheon. Systematic robbery is so far a recognised mode of life among the Magahiya Dams that it has impressed itself on their Religion, and a distinct ritual is ordained for observance by those who go forth to commit a burglary. The object of veneration on these occasions is Sansari Mai, whom some hold to be a form of Kali, but who seems rather to be the earth-mother known to most primitive Religions. No image, not even the usual lump aT clay, is set up to represent the goddess: a circle one span and four fingers in diameter is drawn on the ground and smeared smooth with cowdung. Squatting in front of this the worshipper gashes his left arm with the curved Dam knife (kata1'i), and daubs five streaks of blood with his finger in the centre of the circle, praying in a low voice that a dark night may aid hia designs; tbat his booty may be ample; and that he and his gang may escape detection. 1 "Labra movet metuens andiri: pulchra Laverna, Da mihi fal1ere, da justo sanctoque videri, Noctem peccatis et fraudibus objice nubem,"2

Funeral ceremonies

According to Dr. Wise it is universally believed in Bengal that Doms do not bury or burn their dead, but i unora oeremomes. dismember the corpse at night, like the inhabit¬ants of Tibet, placing the pieces in a pot and sinking them in the nearest river or reservoir. This horrid idea probably originated From the old Hindu law which compelled the Doms to bury their dead at night. The Dams of Dacca say that the dead are cast into a river, while the bodies of the rich or influential are buried. When the funeral is ended each man bathes, and successively touches a piece of iron, a stone, and a lump of dry cowdung, after¬wards making offerings of rice and spirits to the manes of the deceased, while the relatives abstain from flesh and fish for nine days. On the tenth day a swine is slaughtered, and its flesh cooked and eaten, after which quantities of raw spirits are drunk until every body is intoxicated. In Western Bengal and Behar the usual practice is to burn the dead and present offerings to the spirit of the deceased on the eleventh day, or, as some say, on the thirteenth. Before going to the place of cremation the Behar Doms worship Masan, a demon who is supposed to torment the dead if not duly propitiated. Burial is occasionally resorted to, but is not common, except in the case of persons who die of cholera or small-pox and children under three years of age. In these cases the body is laid in the grave face downward with the head pointing to the north.

Habitas and customs

" By all classes of Hindus," says Dr. Wise, "the Dom is regarded with both disgust and fear, not only on account of his habits being abhorrent and aboninable boemg a orren an a omma e, but also because he is believed to have no humane or kindly feelings. To those, however, who view him as a human being, the Dom appears as an improvident and dissolute man, addicted to sensuality and intemperance, but often an affeotionate husband and indulgent father. As no Hindu can approach a Dom, his peculiar customs are unknown, and are therefore said to be wicked and accursed. A tradition survives among the Dacca Doms, that in the days of the Nawabs their ancestors were brought from patna for employment as executioners (jallad) and disposers of the dead-hateful duties, which they perform at the present day. On the paid establish¬ment of each magistracy a Dom hangman is borne, who officiates whenever sentence of death is carried out. On these occasions he is assisted by his relatives, and as the bolt is drawn shouts of 'Dohai

1 The whole of this business was acted before me in the Buxar Central Jail by a number of Magahiya Doms undergoing sentence there. Several of them had their left arms scarred from the shoulder to the wrist by assiduous worship of the tribal Laverna.. 2 Horace, Epist. i. 16, 60. MaharanI! ' or 'Doha! Judge Sahib' are raised to exonerate them from all blame."

Attend Hindu funerals

The peculiar functions which the caste performs at all Hindu funerals may be observed by all visitors to Benares, and are described by Mr. Sherring as follows :-"On the arrival of the dead body at the place of cremation, which in Benares is at the base of one of the steep stairs or ghats, called the Burning Ghat, leading down from the streets above to the bed of the river Ganges, the Dom supplies five logs of wood, which he lays in order upon the ground, the rest of the wood being given by the family of the deceased. When the pile is ready for burning, a handful of lighted straw is brought by the Dom, and is taken from him and applied by one of the chief members of the family to the wood. The Dom is the only person who can furnish the light for the purpose; and if from any circumstance the services of one cannot be obtained, great delay and inconvenience are apt to arise. The Dom exacts his fee for three things, namely, first, for the five logs; seoondly, for the bunch of straw; and thirdly, for the light." It should be added that the amount of the fee is not fixed, but depends upon the rank and circumstances of the deceased. In Eastern Bengal, acoording to Dr. Wise, the services of the Dom at the funeral pyre are not now absolutely essential. Of late years, at any rate in Dacca, household servants carry the corpse to the burn-ing ghat, where the pyre constructed by them is lighted by the nearest relative.

Social status

The degraded position forced upon all Doms by reason of the functions which some or them perform is on the Whole acquiesced in by the entire caste, most of whom, however, follow the comparatively cleanly occupation or making baskets and mats. rraking rood as the test of social status, it will be seen that Doms eat beef,l pork, horse-flesh, fowls, ducks, field-rats, and the flesh of animals which have died a natural death. All of them, moreover, except the Bansphor and Chapariya sub-castes, will eat the leavings of men of other castes. To this last point one exception must be noted. No Dom will touch the leavings of a Dhobi, Q nor will he take water, sweetmeats, or any sort of food or drink from a man of that caste. The aversion with which the Dhobi is regarded i so pronounced that Doms or Behar have assured me that they would not take food !rom a Muham-madan who had his water fetched for him by a washerman of his own Religion. The reason is obscure. Some people say the Dhobi is deemed impure because he washes women's clothes after childbirth; but this fact, though conclusive enough for the average Hindu, would not, I imagine, count for much with a Dom. Moreover, the Doms themselves say nothing of the kind, but tell a very singular story to account for their hatred of the Dhobis. Once upon a time.

In Murshedabad and Eastern Bengal they profess to abstain from beef and hold themselves superior to Muchis and BaUl'is for so doing. In Assam buffalo meat is also forbidden.

2 Some Doms say they will not eat the leavings of Dosadhs and ChamBrs, but this refinement is not general.

they say, Supat Bhakat, the ancestor of the Doms, was retul'lling tired and hungry from a long journey. On his way he met a Dhobi going along with a donkey carrying a bundle of clothes, and asked llim for food and ill•ink. The Dhobi would give him nothing and abused him into the bargain, whereupon Sup at Bhakat fell upon the Dhobi, ill'ove him away with blows, killed his donkey, and cooked and ate it on the spot. After he had. eaten he repented of what he had done, and seeing that it was all the Dhobi's fault declared him and his caste to be accursed for the Doms for ever, so that a Dom should never take food From a Dhobi or eat in his house. The legend may perhaps be a distorted version of the breach of some primitive taboo in which Dhobis and donkeys somehow played a part. Doms will not touch a donkey, but the animal is not regarded by the caste in the light of a totem. In this connexion I may mention the curious fact that the Ankuria. and Bisdelia Doms of Birbhum will not hold a horse or kill a dog, nor ,will they use a dao with a wooden handle, explaining that their ancestors always worked with handleless daDS, and that they are bound to adhere to the ancient custom. The prej udice against killing a dog seems at first sight to suggest some connexion with the Bauris; but it may equally arise

from the fact that one of the duties of scavenging Doms in towns is to kill ownerless dogs.

Occupation

Doms believe their original profession to be the making of . baskets and mats, and even the menial and soavenging sub -castes follow these occupations to' some extent. About half of the caste are believed to have taken to' agriculture, but none of these have risen above the rank of occupancy raiyats, and a large proportion are nomadic cultivatoTs and landless day-labourers. In the south of Manbhum a small numbeI' of rent¬free tenures, bearing the name sibotta1', and supposed to be set apart for the worship of the god Siva, are now in the possession of Doms¬a fact of which I can suggest no explanation. The Bajunia sub¬caste are employed to make highly discordant music at marriages• and festivals. His women-folk, however, only perform as musicians at the wedding of their own people, it being considered highly derogatory for them to do so for outsiders. At home the Domni manufactures baskets and rattles for children. A single wander¬ing branch of the Magahiya sub-caste has eamed for itself a reputation which has extended to the whole of that group. "The' Magahiya Doms of Champaran," says Mr. Beames, are a race of professional thieves. T'hey extend their operations into the contiguous districts of Nepal. They are rather dainty in their operations,. and object to commit burglary by digging through the walls of houses: they always enter a house by the door; and if it is• dark, they carry a light. Of course all this is merely done by way of bravado. Magahiyas never live long in one plaoe. They move about constantly, pitching their ' ragged little reed tents or sirhs outside a village or on a grassy patch by the roadside, like our gipsies, til1 they have done al1 the plundering that offers itself in the neighbourhood, when they move off again." The popular belief that all Magahiya Doms are habitual criminals is, however, a mistake.

Bnrglfll'y is Iulloweu as a profession only by the wandering members of that sub-caste. The Magahiyas of Gya are peaceable basket¬makers and cultivators, who regard thieving with as much horror as thE-ir neighbours, and know nothing of the Laverna cult of Sanschi Mai, whom they identify with .ragadamM, the small-pox goddess, one of a group of seven sisters presiding over various diseases. There seems, indeed, reason to believe that the predatory habits of the gipsy Magahiyas of Champaran are due rather to force of circumstances than to an inborn criminal instinct; and the success of the measures. introduced for their reclamation by Mr. E. R. Henry while Magistrate of Champaran affords grounds for the hope that they may in course of time settle down as peaceable cultivators.

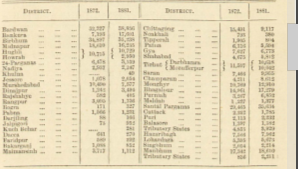

The following statement shows the number and distribution ot Doms in 1872 and 1.881 :¬