Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A profile

The Times of India, Jul 27, 2015

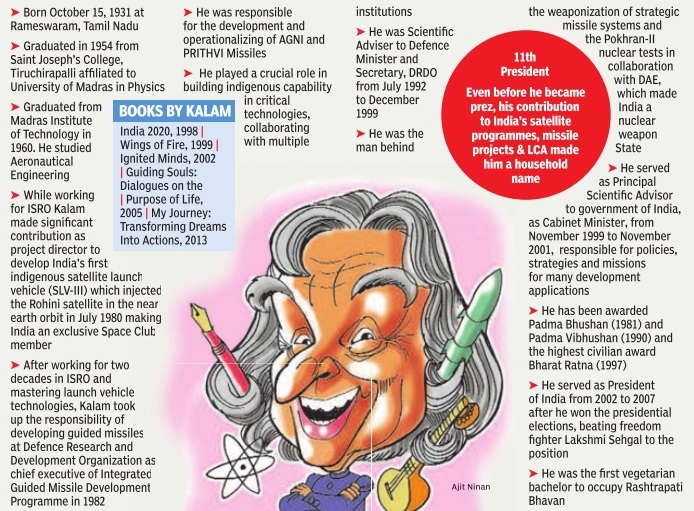

Born on October 15, 1931, at Rameswaram in Tamil Nadu, Dr Avul Pakir Jainulabdeen Abdul Kalam, specialized in aeronautical engineering from Madras Institute of Technology. Dr Kalam made significant contribution as project director to develop India's first indigenous satellite launch vehicle (SLV-III) which successfully injected the Rohini satellite in the near earth orbit in July 1980 and made India an exclusive member of Space Club. He was responsible for the evolution of Isro's launch vehicle programme, particularly the PSLV configuration.

After working for two decades in Isro and mastering launch vehicle technologies, Dr Kalam took up the responsibility of developing indigenous guided missiles at Defence Research and Development Organisation as the chief executive of integrated guided missile development programme (IGMDP).

He was responsible for the development and operationalization of Agni and Prithvi missiles and for building indigenous capability in critical technologies through networking of multiple institutions.

He was the scientific adviser to defence minister and secretary, department of Defence Research & Development from July 1992 to December 1999. During this period he led to the weaponisation of strategic missile systems and the Pokhran-II nuclear tests in collaboration with department of atomic energy, which made India a nuclear weapon State. He also gave thrust to self-reliance in defence systems by progressing multiple development tasks and mission projects such as light combat aircraft.

As chairman of Technology Information, Forecasting and Assessment Council (TIFAC) and as an eminent scientist, he led the country with the help of 500 experts to arrive at Technology Vision 2020 giving a road map for transforming India from the present developing status to a developed nation. Dr Kalam has served as the principal scientific advisor to the government of India, in the rank of Cabinet minister, from November 1999 to November 2001 and was responsible for evolving policies, strategies and missions for many development applications. Dr Kalam was also the chairman, ex-officio, of the scientific advisory committee to the Cabinet (SAC-C) and piloted India Millennium Mission 2020.

Dr Kalam took up academic pursuit as professor, technology & societal transformation at Anna University, Chennai from November 2001 and was involved in teaching and research tasks. Above all he took up a mission to ignite the young minds for national development by meeting high school students across the country.

In his literary pursuit four of Dr Kalam's books - "Wings of Fire", "India 2020 - A Vision for the New Millennium", "My journey" and "Ignited Minds - Unleashing the power within India" have become household names in India and among the Indian nationals abroad. These books have been translated in many Indian languages.

Dr Kalam was one of the most distinguished scientists of India with the unique honour of receiving honorary doctorates from 30 universities and institutions. He was awarded the coveted civilian awards - Padma Bhushan (1981) and Padma Vibhushan (1990) and the highest civilian award Bharat Ratna (1997). He was a recipient of several other awards and fellow of many professional institutions.

Dr Kalam became the 11th President of India on July 25, 2002.

His focus was on transforming India into a developed nation by 2020.

10 life lessons from Kalam

The Times of India, July 27, 2015

Former President & eminent scientist Dr APJ Abdul Kalam passed away in Shillong on Monday. Kalam collapsed during a speech at IIM Shillong and was immediately rushed to the nearby Bethany Hospital.

Here are some of Kalam’s inspirational sayings through which he will be remembered forever

1 “You have to dream before your dreams can come true.”

2 “If a country is to be corruption free and become a nation of beautiful minds, I strongly feel there are three key societal members who can make a difference. They are the father, the mother and the teacher.”

3 “My message, especially to young people is to have courage to think differently, courage to invent, to travel the unexplored path, courage to discover the impossible and to conquer the problems and succeed. These are great qualities that they must work towards. This is my message to the young people.”

4 “To succeed in your mission, you must have single-minded devotion to your goal.”

5 “Let me define a leader. He must have vision and passion and not be afraid of any problem. Instead, he should know how to defeat it. Most importantly, he must work with integrity.”

6 “Great dreams of great dreamers are always transcended.”

7 “Let us sacrifice our today so that our children can have a better tomorrow.”

8 “Man needs his difficulties because they are necessary to enjoy success.”

9 “Look at the sky. We are not alone. The whole universe is friendly to us and conspires only to give the best to those who dream and work.”

10 “You see, God helps only people who work hard. That principle is very clear.”

1931-2013

The Times of India, Jul 28 2015

Sagarika Ghose

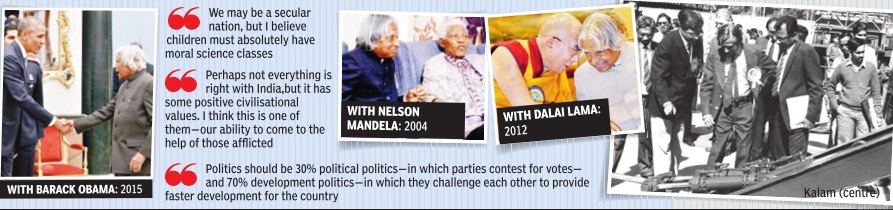

Avul Pakir Jainulabdeen Abdul Kalam was a President like no other.The floppy silvery mop curling on his forehead, the twinkling eyes and the ever smiling visage seemed to radiate boundless infectious energy and positivity . Kalam embodied the new India story . Born into a poor Muslim family in Tamil Nadu, he rose by sheer force of education and conviction to become a driving force behind India's space and missile programmes, chief scientific adviser to the PM, boss of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) and finally , President of India. Long after he'd left Rashtrapati Bhavan, he remained high on ev ery popularity poll. In the US, he would have been called a `rock star'.

On Monday , India's Missile Man-turned-People's President went as suddenly -at a youthful 83 -as he had arrived centre stage to become a national icon. Kalam collapsed while delivering a lecture at the Indian Institute of Management, Shillong at around 6.30pm. He was rushed to Bethany Hospital but the doctors couldn't save him. His body is being flown to Delhi this morning.

To a new aspirational India, he was a President refreshingly free of political affiliation, a genial figure who embodied the joy and adventure of science, whose messages were so attractive to the young precisely because they were so simple and straightforward. APJ Abdul Kalam redefined the presidency in unique ways.

His herbal garden at Rashtra pati Bhavan, the instant connect with kids, his own unquestioned integrity, even the fact that he was a lifelong bachelor, made him somewhat of an urban legend for a generation looking for homegrown heroes. The fact that he was responsible for the development of the five missiles, Prithvi, Trishul, Akash, Nag and Agni, added to his charm for the young.

Kalam's biggest asset for a changing India was that he was an outsider in politics, someone who instead of preserving Rashtrapati Bhavan only for high official ceremonies, opened it up to the public. In fact, he did to the Indian presidency what Princess Diana to some extent did to the British monarchy (albeit far less controversially): He demystified it, while making himself a feel-good First Citizen, as if his moral purpose lay not in ceremonial matters of state but among school and college students. Unmoved by the trappings of power, he kept travelling, meeting the young and sharing ideas even after leaving the presidency . His best-selling autobiography `Wings of Fire' was written in a beguilingly accessible style and told a story of a journey from hardship to professional success in a way that mirrored the aspirations of India in the 21st century .

He himself seemed to prefer nonpoliticians as president. Once when asked how he would feel if Narayana Murthy succeeded him as President, Kalam beamed, “Fantastic, fantastic, fantastic.“ Indians relied on Kalam to do the right thing. When the prospect of being drawn into a contest against Pranab Mukherjee arose, Kalam said, “My conscience is not permitting me to contest.“

After he ceased being President, travellers were often pleasantly surprised to see Kalam standing in queue during security check at airports, accepting no special VIP privileges.

Kalam's weak moment may have been when he was forced to sign the controversial dissolution of the Bihar assembly in the infamous order at midnight in Moscow, but then he also showed he was no one's man when he sent back a number of NDA proposals for reconsideration, just as he later sent back twice the file on Sonia Gandhi's office-of-profit issue.

Kalam was the President that 21st century India warmed to, an India that was trying to wrench itself free of the clutches of caste, religion and family. He was the President who embodied high science as well as one who knew about the life of third-class long queues for water. He was the President who designed missile programmes and flew Sukhois but one whose message was primarily for kids and not for ceremonial high grandees. His magnificent eccentricites made him lovable, his life was a mirror of an aspirational India seeking a new narrative.

Post Gujarat riots, 2002

The Times of India May 22 2015

Post-riots, Vajpayee didn't want me to go to Guj: Kalam

Akshaya mukul

`Wondered during office of profit row if I should resign'

Former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee did not want the then President Mr. APJ Abdul Kalam to visit Gujarat in the aftermath of 2002 riots. Kalam also faced the moral dilemma whether to resign during the office of profit controversy in 2006 when he had to reluctantly sign the bill that kept certain posts out of the list. This and few other temporal matters find mention in Kalam's spiritual biography of Pramukh Swami, head of Swaminarayan sect, to be released early next month. The former President claims many of his problems could be resolved with the blessings of the Pramukh Swami.

Transcendence: My Spiritual Experiences with Pramukh Maharaj published by Harper Element, an imprint of HarperCollins, talks of Kalam's visit to Gujarat in 2002 after the riots. He writes that af ter the devastating earthquake of 2001, “mindless violence of 2002 dealt us another unexpected blow“ “Innocents were killed, families were rendered helpless, property built through years of toil was destroyed. The violence was a crippling blow to an already shattered and hurting Gujarat,“ he writes. As President, he wanted to visit the state. But as he writes, “PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee was discomfited by my decision. He asked me, `Do you consider going to Gujarat at this time essential'? I replied, `I must go and talk to the people as a President. I consider this my first major task.' “ He says there was fear that then chief minister Narendra Modi will boycott the trip. However, he says, Modi and his cabinet colleagues accompanied him.

During the office of profit controversy in 2006, Kalam says, “I experienced an intense moral dilemma: should I have signed or should I resign?“ The conundrum, he says, could be resolved only after meeting Pramukh Swami in Delhi.

Kalam writes that after Jaya Bachchan had to resign, “opposition parties smartly turned the fallout from this disqualification against Sonia Gandhi as she was the chairperson of the National Advisory Council“. However, he writes, when the Parliament (prevention of disqualification) Amendment Bill 2006 came to him for approval, “I felt the manner in which exemptions were given was arbitrary“. Kalam says that he first returned the bill for reconsideration but since government sent it back to him without changes, he had no option but to sign the bill.

There is also an episode of Kalam visiting late Khushwant Singh in his house to enquire about his health. Singh told Kalam that he wanted to trash the President's books that had come for review but later realized he was a good writer.

The book co-authored with Arun Tiwari calls “Swaminarayan temples and Akshardhams“ the “sanctuaries of pious and virtuous living“. The book has an interesting cast of characters and events while the story of Pramukh Swami runs throughout the text. Having first met Pramukh Swami in the summer of 2001, Kalam writes he “felt a strange connection with something that exists in the realm of spirit--the part that is closest to the Divine“. “I felt I had acquired a sixth sense,“ he writes.

The karmayogi

The Times of India, Jul 28 2015 S Nambi Narayanan

When I got an interview call from from Thumba Equatorial Rocket Launching Station (TERLS) in Thiruvananthapuram for the job of a technical assistant (design) in September, 1966, I knew precious little about the organization. A bunch of young people handpicked by Vikram Sarabhai were working out of an old church in the sleepy fishing village of Thumba in Thiruvananthapuram, with the common goal of making rockets. To know more, I went to a lodge called Indira Bhavan where some of the scientists were put up. As I was enter ing, a man in a pale blue shirt and dark trousers was coming down the stairs. I introduced myself as an applicant. He replied: “I am A P J Abdul Kalam, rocket engineer.“

Soon I found myself among the small group of men at the church with little resources and big dreams.Kalam, as my team leader, gave my first assignment -to make an explosive bolt. Our association started there, and continued till Kalam's end.He was a karmayogi. Without a family or any possession worth mentioning, he dedicated himself to work.

Life, for Kalam, meant setting goals and achieving them steadfast. Death, he never bothered about. Once, while I was doing an experiment on the inert behavior of a variety of gunpowder in low pressure, Kalam insisted on seeing it up close. He stood so close to catch the action that his famous nose touched the jar in which the gunpowder was to be ignited. According to theory , it would not ignite.

But a helper had forgotten to switch on the vacuum pump that would reduce the pressure in the jar. This I realised when the countdown had reached the final five seconds.I threw myself over Kalam and the two of us landed on the floor. Glass pieces flew in all directions like bullets. While I thanked God that neither of us was injured, Kalam stood up, dusted his trousers, and said: “Hey man, it did explode!“ Later I pursued liquid propulsion systems, while Kalam stuck to his love -solid propulsion. When I was heading a team of Isro scientists at the Viking engine joint venture in France in 1975, Kalam visited us and had kind words for us, though he was a hardcore votary of solid propulsion systems. On a personal level, too, Kalam was always helpful. This was the time when I was finding it difficult to get my six-yearold son into a decent Englishmedium school in France. I wanted to send him back to India. Kalam, visiting us in Vernon, offered to take my son back to India. He held the boy's hand through the journey till he was safely deposited at my sister's place.

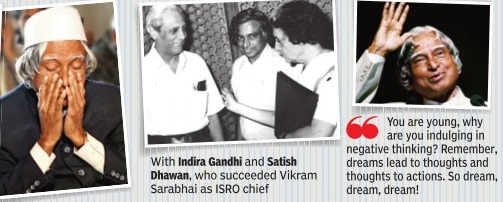

Neither criticism nor praise moved Kalam. And Isro chairmen like Vikram Sarabhai and Satish Dhawan knew Kalam's vision and let him do what he wanted. At the core of India's first success with satellite launch vehicles was Kalam's single-minded pursuit.

The greatness of the man was his intellectual honesty . In one of our recent interactions, I told Kalam that he might not find everything in my upcoming book flattering. He said: “Then I will write the preface.“

That was not to be.

Kalam: The author

The Times of India, Jul 28 2015

Sivakumar B

Kalam wielded `kalam' with flair

Kalam' s books flew off shelves as soon as they were published and can be probably found in every library in the country . Amidst his tight schedule, Kalam found time to put pen to paper, almost every day. Popular as a scientist and President, there was anoth er side to Kalam --the writer. His books, including his autobiography `Wings of Fire' and his last book on his guru released recently have been bestsellers. `Wings of Fire,' has been translated in 13 languages including Braille. It has also been translated into Chinese and French.

“His audience was everybody who wanted a better India,“ said Kapish Mehra of Rupa Publications.Kalam's books varied from pure science to his vision for the country and his love for children, said Mehra. “Kalam being a self-made man was an instant connect with the common man and students. His writing was simple and easily understandable,“ said Penguin Publications managing director Udayan Mitra. Kalam's book `My Journey' published by Penguin in 2013 has sold more than 1 million copies. His last book, released across the country on Saturday was `Transcend ence-My Spiritual Experiences' with Pramukh Swamiji. In this book he records his life from Rameswaram.

“Each evening the head priest of the Rameswaram temple, the church priest and my father who was an imam, would meet over a cup of tea, and dis cuss issues affecting the community ,“ says Kalam in the book. In the book he also mentions his previous gurus Satish Dhawan and Vikram Sarabhai -but concludes that his ultimate guru was Pramukh Swami, head of the Swaminarayan sect.

Kalam: Presidency

The Times of India, Jul 28 2015

He might be called the Accidental President. For an apolitical and other-worldly APJ Abdul Kalam, it was rather fortuitous how a defence scientist reached the highest office of the Republic and became one of the more popular Presidents. It all started when a consensus-seeker Atal Bihari Vajpayee sought a name acceptable to Congress for Rashtrapati Bhavan. By all accounts, BJP preferred PC Alexander, former close aide of Indira Gandhi, but Sonia Gandhi vetoed his name.

And out of the blue came Kalam's name. Missile Man and Muslim to boot, even the reluctant Congress couldn't say no. Surprise of surprises: Kalam was discovered neither by wily Pramod Mahajan nor imaginative Vajpayee, but by son of the soil Samajwadi, Mulayam Singh Yadav.

He came to mean many things to many people, all converging in making him everyone's choice. In 2002, he was elected, reigned supreme till 2007 by carving a niche for himself as “Children's President“ but never retired into the sunset till life came calling on July 27, 2015.

When the Indo-US nuclear deal was in limbo, Mulayam's word mattered the most. On July 3, 2008, with aide Amar Singh in tow and the world wanting to know which way the wily wrestler would weigh, Mulayam drove to Kalam's residence, stayed in for half an hour and emerged to tell the waiting reporters, “Kalam told us that the deal is in the interest of the nation. Kalam explained to us the nuclear deal.“

With the passage of time and with the world believing he had faded away , Kalam surprised many by his longevity .In 2012, with Congress struggling to find the name for Presidency that all its allies would sign up on, Mulayam and a couple of regional satraps pitched for the scientist.

The whisper turned into a buzz. Kalam kept silent, but the word was out that he wouldn't mind a consensus. But when the suspense took the shape of speculative unrest, he clarified he was not in the race.

While he came to office courtesy Vajpayee-led BJP, he raised as many queries on NDA files as he did with Congress. But again, by swinging the Mulayam vote for the nuclear deal, he helped Congress like nothing.

The Peoples’ President

The Times of India, Jul 29 2015

Arati R Jerath

He narrowed distance between president & public

By any yardstick, A P J Ab dul Kalam was an odd choice for the post of President of India. He was not a veteran politician like most of his predecessors, nor a man of letters in the manner of S Radhakrishnan or Zakir Husain. Yet, few have impacted the Indian presidency as much as this eminent scientist who blew in like a breath of fresh air, turning a ceremonial figure into a popular people's icon. Two things set Kalam apart. One, his determination to break down walls of pomp and protocol that separated the institution of President from aam admi. The other, his zeal to turn everything he did into a national mission.“Vajpayeeji, I consider this to be a very important mission, he told the then PM when he accepted the offer to become India's eleventh President, as revealed in his autobiography `Turning Points: A Journey Through Challenges'.

Kalam took his presidency seriously. He attacked it with the same enthusiasm as a scientific research project and dared to push the envelope to see how far he could go to reinvent a largely figurehead position patterned on British monarchy . He did away with the formal bandhgala for invitees to the presidential At Home receptions. He'd blithely jump over security cordons around VVIP enclosures to mingle with other guests. Late BJP neta Pramod Mahajan, would recall how difficult it was to persuade Kalam to agree to an image makeover, from the absentminded scientist look to a more formal get-up. Vajpayee once revealed in an interview that Kalam was reluctant to wear a bandhgala even for his swearing-in ceremony .

But through everything, Kalam's love for people, particularly children, burned bright.It became his USP , prompting a journalist to dub him the “People's President. It was Kalam who threw open the hallowed portals of the imposing Lutyens' edifice on top of Raisina Hill to people from all walks of life. He reached beyond Delhi's charmed circle to include outsiders in ceremonial events.One year, he invited sportspersons to attend the Republic Day reception. Another year it was various sarpanches. A third year, he called postmen.

When the Mughal Garden at Rashtrapati Bhavan opened every year for the public, Ka lam would spend time chatting with visitors. He travelled extensively and instead of confining himself to ribboncutting events, insisted at least one programme be an informal interaction with students.

Perhaps it was Kalam's ability to connect with people that helped him master the challenges of his role as First Citizen of India. His apolitical background added a non-partisan integrity to his decisions even when they had the potential to create controversy .

His first move after being sworn in was to insist on visiting Gujarat's riot-affected areas. As he recalls in his autobiography , when Vajpayee queried him on this, Kalam said, “I consider it an important duty so that I can be of some use to remove the pain ... bring about a unity of minds... The visit turned out well with then CM Narendra Modi accompanying him to the relief camps.

Presidents over the years have left behind varying legacies. Kalam is unique in the hall of fame because he was the first to try and narrow the distance between the institution of president and the people of India. He was the first to show that the President can be a real person who inspires and leads. There is little doubt that his presidency will remain his defining moment. Kalam ensured the era of the monarchical President is over.

Kalam: The missile man

The Times of India, Jul 28 2015

We need missiles as strength respects strength, he would say

Much before he became “a people's President“ in 2002, APJ Abdul Kalam was already a national icon as the “Missile Man of India“, an inspiration to children and scientists around the country . Known more for his inspirational leadership of the scientists who worked under him, Kalam was the brainchild behind the launch of the country's indigenous integrated guided missile development programme (IGMDP) in 1983.

Though dogged by time and cost overruns, IGMDP laid the foundations from which India gate-crashed into the super-exclusive club of nations that can now boast of being capable of developing inter-continental ballistic missile, the over 5,000-km Agni-V missile, capable of hitting even the northernmost part of China. Kalam, as DRDO chief, and DAE director R Chidambaram, played a pivotal role in covertly planning and organizing the Pokhran-II nuclear tests in 1998, successfully managing to fool US satellites and other intelligence-gathering mechanisms.

DRDO scientists remember him as a person who worked round-the-clock, always informal, had a spartan lifestyle and an easy-going demeanour. “Strength respects strength“ was his credo whenever he was quizzed on why India needs its own long-range ballistic missiles or a main battle tank.

Rocket man: “Major General Prithviraj'

The Times of India, Jul 29 2015

Chidanand Rajghatta

How Kalam's role helped avert `Hindu bomb' tag

Abdul Kalam did not visit the US in the years he was India's President (2002-2007). It was the aftermath of 911; Washington was in a red haze and had launched a “war on terror“.There was little appetite in the Bush administration, yet to get its teeth into the USIndia nuclear deal, to host a titular head of state, although it had already begun recalibrating its ties with India.Manmohan Singh was the goto man. Kalam may well have been the “to-go man. After all, he'd defied US sanctions for over two decades to help India become a de facto nuclear and ballistic missile power, circumventing a US-led effort by world powers to circumscribe it. Of course, Kalam had visited the US before.As a young scientist, he spent time in the 1960s at Nasa's Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, and at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, in an era when Washington happily patronized India's fledgling space programme. But things went south after Richard Nixon's toxic tilt in 1971 and In dia's first nuclear test in 1974, resulting in years of sanctions on the country's nuclear and missile programme.

Struggling to get India's space programme going in the face of an inimical USled sanctions regime, Kalam was at the wrong end of Washington's technology denial regime. The experience motivated him to indigenize India's space and nuclear programme. By the time he adopted the nom de guerre “Major General Prithviraj and donned military camouflage during the Shakti tests in 1998 to escape US spy satellites and spooks tasked with monitoring India's nuclear programme, he had become a past master at working his way around US's restrictions.

Taking on the name “Prithviraj may or may not have indicated the comfort with which he carried his syncretic Indian heritage.But his association with India's nuclearization, which he had long pressed for, helped avoid the weapon from being dubbed a “Hindu bomb -a term western headline writers and non-proliferation ayatollahs were all too eager to bestow as a counterpoint to the “Islamic Bomb“.

India's return to the nuclear centrestage was coloured by corrosive commentary on bouts of Hindu triumphalism that followed the Shakti tests.The tests were attributed as much to BJP's political compulsions as to India's security needs. But there was a problem with the “Hindu bomb narrative. One of its principals was an unusual Muslim, who read the Bhagvad Gita, listened to Carnatic music, liked to play the Rudra Veena, and had praying rights at the Rameswaram temple.In truth, Kalam was neither Muslim nor Hindu: his religion was learning.

Kalam and the Sri Ramanathaswamy temple

The Times of India, Jul 29 2015

Padmini Sivarajah

Temple that ignited Kalam's mind as a child fascinated him all his life

A tiny shop near the western entrance of Sri Ramanathaswamy temple in Rameswaram was one place that enthralled A P J Abdul Kalam as a child.Kalam once said he developed his interest in flying objects by seeing toys, such as aeroplanes, in the shop that was run by his family . His visits to the shop, apart from fuelling his interest in avionics, also fuelled a fascination for the temple that remained throughout his life. Joint commissioner of Ra manathaswamy temple, C Selvaraj said Kalam had always shown special interest in the temple and visited it whenever he found time. “He would come up to the third corridor of the temple,“ he said.

People of his community still enjoy several privileges during temple festivals. Selvaraj said though there are no documents to prove it, it is believed that people of the Marakayar Muslim community , from which Kalam came, were once the custodians of a set of the temple keys. The temple came under the Hindu Religious & Charitable Endowments Board in 1960 and since then all the keys of the temple are with the government. However, the community had a special status in the temple and was allowed to take part in the float festival held in the month of `Thai' (mid-January to mid-February) every year. The members were allowed to pull the rope of the float and then handed over fruits and flowers. “This may have also been due to the fact that the population was very low then and communal harmony encouraged everybody to come forward to pull the float,“ said Selvaraj.

VHP's Ramanathapuram district secretary A Saravanan said that according to hearsay , the Marakayars had retrieved the idol when it accidentally fell into the temple tank and had since received special attention during the festival.

AQ Khan's view of Dr Kalam

The Times of India, Jul 30 2015

Chidanand Rajghatta

It requires an extraordin ary degree of idiocy and lack of class to speak poorly of a dead person, but when you are a low-life like Abdul Qadeer Khan, being déclassé comes easily .The Pakistani nuclear “scientist,“ better known in world circles as a man who helped his country get the nuclear technology through theft and skullduggery , and worse, tried to spread it to such rogue states as North Korea and Libya, has said in a BBC interview that India's just deceased former President Abdul Kalam was an “ordinary scientist.“

Khan may well be correct.Abdul Kalam did not boast of being an extraordinary scientist, nor did India recognize him as one. What Khan has missed -and this is probably not important to him considering his dismal reputation as a thief, a smuggler, and a proliferator of nuclear technology is that Kalam was an extraordinary human being.

In his death, Kalam in being mourned in India and beyond as a great teacher who ennobled a country and its people with his wisdom and humility . Heck, even the Pakistan government, not known for its fine graces, sent its condolences, not to speak of tributes of tributes from President Obama and leaders across the world.

Contrast this with AQ Khan's own ragged reputation and rotten standing as a fugitive who lives under protection of an intelligence agency best known for fomenting terrorism, a man despised by his own peers and doubted by his own people.Unlike the much-loved Kalam, who traveled across India and across the world including to the US and Europe Khan remains confined to Pakistan, fearful that if he steps out of the country he will be spirited away either by terrorists eager to lay their hands on a nuclear weapon or foreign intelligence agencies wanting to see how much damage he has done in nuclear proliferation.

A metallurgist whose contribution to Pakistan's nuclear program consisted largely of stealing centrifuge blueprints from a European firm that employed him in the 1970s, Khan's role in Pakisc tan's bomb making effort is questioned by his own colleagues. In fact, Pakistanis involved in this operation, commissioned by Z A Bhutto after being routed in the 1971 war, squabbled for credit like schoolboys or like bank robbers fighting over booty when they finally tested their device in 1998 in response to India's nuclear test.

To this day , Pakistanis have a hard time deciding who among AQ Khan, Munir Khan, and Samar Mubarakmand, the three principals involved in the testing, had a greater role in Pakistan's nuclearization. Teamwork it certainly was not judging by their very public scraps.

Again, contrast this with Kalam, who as team leader took the rap for the failure of SLV-3 in the 1980s even as his own boss, Satish Dhawan, also tried to take responsibility as head of ISRO. When ISRO did get its act together and took flight, Kalam was also the first to give credit to his colleagues and subordinates.

Indeed, both under Kalam and subsequently , DRDO's record has not been spectacular. But no one remembers Kalam for that. The intellectual chasm between the two men is evident in their public writing. Anyone who reads AQ Khan's rambling columns in Pakistani newspapers will have a hard time believing he even passed high school.

USA, relations with

Learning rocket science at NASA

Time, July 28, 2015

Ramabhadran Aravamudan

Before he became India’s head of state, Dr. Kalam, who died on Monday aged 83, was one of the country’s most distinguished scientists. Here, a former colleague and friend recalls his time training with a young Kalam in the U.S. in the early 1960s

Back in the 1960s, we were both rookie engineers working for government organizations in India with just a few years of experience behind us—I worked in electronics and he specialized in aeronautics. Both of us had passed out from the Madras Institute of Technology in southern India, although he was older than me and graduated a few years ahead.

But the first time I met A.P.J. Abdul Kalam—or Kalam, as I always knew him—was in a foreign country: the U.S. I’d gone there in December, 1962, and he followed in March, 1963. We were part of a seven-member team dispatched by Vikram Sarabhai, the father of India’s space program, to train with NASA and learn the art of assembling and launching small rockets for collecting scientific data.

I’d already spent a few months training at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre in Greenbelt, Maryland, when Kalam arrived from India. Soon, we were working side by side at NASA’s launch facility in Wallops Island, Virginia. Our lodgings were called the B.O.Q., or the Bachelor Officer’s Quarters, and we’d lunch together at the cafeteria where, because we were both vegetarians, we survived mainly on mashed potatoes, boiled beans, peas, bread and milk. Weekends in Wallops Island were lonely affairs, as the nearest town of Pocomoke City was an hour’s drive away. Thankfully for us, NASA put on a free flight to Washington D.C. for its recruits, so we would head up the to American capital on Friday nights and return to Wallops on the Monday morning shuttle.

It was a memorable experience. I remember one training session where Kalam had to fire a dummy rocket when the countdown hit zero. It was only after half a dozen attempts when he kept firing the rocket either a few seconds too early or too late that the man who went on to become one of India’s best known rocket scientists managed to get it right.

Our American sojourn ended in December, 1963, when we returned to India to help set up a domestic rocket launching facility on the outskirts of Trivandrum, the capital of the southern Indian state of Kerala. It was very different world from NASA. India’s space program was still in its early years and we had to swap our weekend shuttles to Washington for bicycles, our sole mode of transportation in those days.

Quite apart from the change, this presented a practical problem for Kalam: he didn’t know how to ride a bike! He was forced to depend on me or one of the other engineers to ferry him to and from work. When it came to food, if we’d lacked options at the canteen in Wallops Island, in Kerala we had to fend entirely for ourselves: there was no canteen at the nascent launch facility, and we had purchase our lunch at the Trivandrum railway station on the way to work.

Belated acceptability

Chidanand Rajghatta, July 31, 2022: The Times of India

With his crazy-looking hairdo and pronounced accent, he was, more than any other Indian scientist, imbued with a diabolic, mephistophelian avatar in western non-proliferation narrative. But that demonisation eventually turned to admiration

Avul Pakir Jainulabdeen (APJ) Abdul Kalam did not visit the US in the years he was the President of India (2002-2007). It was the aftermath of 9/11; Washington was in an angry red haze and had launched a war on terror”. There was little appetite in the Bush administration, which was yet to get its teeth into the US-India nuclear deal, to host a titular head of state, although it had already begun recalibrating its ties with India. Former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh was the go-to man. Kalam may well have been the “to-go” man.

After all, he had defied US sanctions for more than two decades to help India eventually become a de facto nuclear and ballistic missile power, circumventing an American-led effort by world powers to “cap, roll-back and eliminate” New Delhi's progress.

With his crazy-looking hairdo and pronounced desi accent, he was, more than any other scientist in the Indian establishment, imbued with a diabolic, mephistophelian avatar in western non-proliferation narrative — India’s Dr Strangelove.

Kalam had visited the US before. As a young rocket scientist, he had spent time in the 1960s at Nasa's Langley Research Centre in Hampton, Virginia, and at the Goddard Space Flight Centre in Greenbelt, Maryland, on either side of the US capital, in an era when Washington happily patronised India’s fledgling space programme.

But things went south after Richard Nixon’s toxic tilt in 1971 and India’s first nuclear test in 1974, resulting in long years of ever-tightening sanctions on the country’s nuclear and missile programme.

Struggling to get India’s space programme going in the face of inimical US-led sanctions, Kalam was at the wrong end of Washington’s technology denial regime. The experience motivated him to work on indigenising every aspect of India’s space and nuclear programme, not always with great success.

Kalam had his early training at Nasa's Langley Research Centre (pictured above) in 1963. Over five decades later, in 2017, scientists at NASA named a new organism discovered in space after him By the time he adopted the nom de guerre “Major General Prithviraj” and donned military camouflage during the Shakti tests in 1998 to escape US spy satellites and spooks tasked with monitoring India’s nuclear programme, he had become a past master at working his way around American restrictions.

Taking on the name “Prithviraj” may or may not have indicated the comfort with which he carried a syncretic Indian heritage. But his association with India’s overt nuclearisation, which he had long pressed for as its “missile man”, perhaps helped avoid the weapon being dubbed a Hindu bomb”. It was a term that western headline writers and non-proliferation nabobs were all too eager to bestow as a counterpoint to the “Islamic Bomb”.

As it is, India’s return to the world nuclear centrestage has been coloured by corrosive commentary on bouts of Hindu triumphalism that followed the Shakti tests. Some analysts attributed the tests as much to Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) domestic political compulsions and instinct for survival — it led a minority government — as to India’s security needs or strategic foresight.

So there was a spate of editorials, analyses and cartoons with a Hindu angle — from India’s Hindu prime minister offering his home minister Hindu sweets” to a weekend New York Times story that was accompanied by a reproduction of a painting of Shiva, with five heads, 10 arms, and a garland of skulls. Other commentaries spoke of a recidivist, revanchist mood in India, flogging the usual cliché-d images — snake charmers, fakirs, even sati and Kipling.

But there was one problem with the “Hindu bomb” narrative. One of its principals was a Muslim, even though he was an unusual one: Kalam read the Bhagavad Gita, listened to Carnatic music, liked to play the Rudra Veena and even had praying rights at the Rameswaram temple. In fact, he had seldom been seen at a mosque; one rare public visit to the Fatehpuri Masjid in 2007 occasioned much surprised commentary. In truth, Kalam professed to be neither Muslim nor Hindu in public: His religion was learning. Not that he disdained religion. In fact, when he did resume his US visits after demitting the presidential office, one of his trips was to attend the anniversary of the JSS spiritual mission in Maryland outside Washington. Associated with the Suttur mutth (monastery), the mission is avowedly Hindu, but Kalam chose to recognise its commitment to education above all else.

Kalam demonstrated that pique was not part of his psyche despite Washington's one-time demonisation. He went on to accept honorary degrees from several US universities including Carnegie Mellon. Here, an aerial photograph of Carnegie Mellon’s campus

In his book Ignited Minds, the former president also cited my book, The Horse That Flew, referring in particular to a passage that described a Silicon Valley eco-system where enterprise and teamwork trumped religion, politics and even nationality.

The US itself had secretly begun citing his ascension as president as proof that even under a BJP/NDA government, notwithstanding aberrations, India was well and truly secular, and the opportunity the country’s democracy offered to minorities boded well in the fight against terrorism.

“With a Muslim president (Abdul Kalam) occupying the highest political position in the country, Muslims have been encouraged to seek political power in electoral and parliamentary politics, all but eliminating the appeal of violent extremism,” then US ambassador to New Delhi David Mulford wrote to Washington, according to a cable cited by Wikileaks.

In more recent years, Kalam, like the current PM, demonstrated that pique was not part of his psyche despite Washington's one-time discrimination and demonisation. There was the odd security flub and protocol gaffe even on post-2007 visits to the US, but he took it in his stride, accepting honorary degrees from University of Houston and Carnegie Mellon among others, while unfailingly speaking about his first love: Learning.

In more than one way, he was an inspirational man of words.

Here is the statement issued by the Obama White House on Kalam's death: The White House

Office of the Press Secretary

July 28, 2015

Statement by the President on the Death of Former Indian President Dr APJ Abdul Kalam On behalf of the American people, I wish to extend my deepest condolences to the people of India on the passing of former Indian President Dr APJ Abdul Kalam. A scientist and statesman, Dr Kalam rose from humble beginnings to become one of India’s most accomplished leaders, earning esteem at home and abroad.

An advocate for stronger US-India relations, Dr Kalam worked to deepen our space cooperation, forging links with Nasa during a 1962 visit to the United States. His tenure as India’s 11th president witnessed unprecedented growth in US-India ties. Suitably named “the People’s President”, Dr Kalam’s humility and dedication to public service served as an inspiration to millions of Indians and admirers around the world.