Easterine Kire Angami

You can send additional information, corrections, photographs and even Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Location Nagaland, Kohima/ Norway

Contents |

Sources

Introduction

Easterine Kire is a poet, novelist, and writer of children’s books. She also writes short stories and some of her short stories are translated to German. Her first novel, A Naga Village Remembered (Ura Academy 2003) was also the first Naga novel in English to be published. She has a Ph.D in English literature from the University of Pune. In 2011 she was awarded the governor’s medal for excellence in Naga literature. Her poetry and books have been translated to German, Croatian, Uzbek, Norwegian and Nepali.

She is currently based in Northern Norway where she concentrates on her writing, and performs jazz poetry with her band, Jazzpoesi.

Easterine Kire (Iralu) has written several books in English including three collections of poetry and short stories. Her first novel, A Naga Village Remembered, was the first-ever Naga novel to be published. Easterine has translated 200 oral poems from her native language, Tenyidie, into English. Her forthcoming books include Forest Song; a volume of spirit stories; and Bitter Wormwood, a novel on the Indo-Naga conflict. Easterine is founder and partner in a publishing house, Barkweaver, which gathers and publishes Naga folktales.

Early life and education

She was born on Easter Sunday, 29 th March 1959 and educated at the Baptist High School, Kohima, for the first ten years of schooling. She continued her studies by getting a pre-university degree at the Kohima College, a BA degree from Shillong and a year of Journalistic studies at Delhi followed by occasional writing in a column for the local newspapers. In the next two years, She worked on a Masters Degree in English Literature.

Aged 5 years, her first memory of the conflict includes lying flat on a cold cement floor with her younger brother, when shots reverberated round their neighborhood. While her Grandfather and brother were in bed, a bullet whizzed over their heads and went through the wall. Her father was shot at but the bullet hit her cousin in the thigh instead. Curfews and continued periods of gunfire were all part of growing up in Nagaland. Frequently, men came to her Grandfather's house with stories to tell of captured men being tortured and killed. But the conflict took on a much uglier face with the emergence of infighting in the 80s. In 1987, a school friend was killed in the heart of Kohima town.

Ever since then, the cycle of killing and counter revenge killing has not abated. Two levels of violence exist in her homeland. On one hand, Indian army atrocities continue. A military convoy began shelling, at random, civilian houses in Kohima in 1995 where many were killed and maimed, including children. A few years before that, many houses were burnt in another town, Mokokchung, resulting in loss of many civilian lives. Civilian killings by the army continue to occur on a smaller scale. On the other level is the infighting from ideological differences between the Naga freedom fighters.

Early career

With a first class MA in Literature, She was appointed as Editor in the State Government of Nagaland's Directorate of Information and Publicity. But after two years, She resigned from the editorial job to become a teacher at the Kohima College and then moved on to a more permanent teaching job at the North Eastern Hill University, Kohima.

While teaching at college and university, She continued to write a column for one of the local newspapers, The Nagaland Observer. Aged 22 in 1982, She published her first volume of poems, Kelhoukevira. Written in English, it was the first volume of poetry to be published individually by a Naga poet. The main poems mourn the warriors of Nagaland killed in the Indo-Naga conflict. In the fifties, She had lost an uncle to the conflict and was to lose two more in subsequent years.

As a lyricist and author

In 1997, while working towards a Ph.D degree, one of her dreams of making a music CD of her poem-songs was fulfilled. She worked with Daphne Kent and Niu Vihienuo. A second dream was fulfilled in 2001 with publishing a volume of poems and short stories with accompanying sketches by good friends of mine, artists from the North-east of India. Her niece, Kevi Z. Savino did most of the colour illustrations. In 2003, She wrote a book with an Australian co-author, Ernie Wombat and the Water Dwellers a fun book about a wombat who falls into a waterway and is pulled by strong currents till he surfaces in Dzüleke in the Naga hills. The book introduces Nagaland through the eyes of an Australian animal and we were happy to look at the Nagas and their habits through the uninformed eyes of a newcomer.

In the same year, She wrote her historical novel A Naga Village Remembered, an account of the last battle between the colonial forces of Britain and the little warrior village of Khonoma. Also categorized as historical fiction, this was again the first novel in English by a Naga writer. Before this, Shürhozelie, the literary pioneer of literature in her language, had already written three novels in Tenyidie. So, literature in Tenyidie, her mother tongue, already rich with both oral and written literature, was a source of inspiration to her. Growing up in Kohima in the 1960s, the conflict fought close to the Naga villages, was never very far from us, the town dwellers.

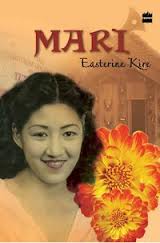

A Terrible Matriarchy ( 2007) by zubaan and MARI ( 2010, harper collins) has received rave reviews and is currently the bestseller amongst the Nagas worldwide. She writes poignant themes from Nagaland and has managed to carve a niche for herself and the upcoming writers of Nagaland, and most importantly of the Nagas around the world. On her Facebook group of MARI, the book, it is easily visible that her appeal stretches much beyond the Nagas and her readership includes other mainstream Indians as well as International readers. 2011 saw her participating in FREE THE WORD FESTIVAL of the English PEN writers.

Film scripts

See Nagaland: Cinema

Present life

From 2000- early 2005, She personally experienced the stress of living in a house that was stalked by armed men at night because of the political writings of her spouse. Threats were also directed at her when an article of mine appeared in the papers protesting the killings. The abnormality of life was something She had resigned myself to, tapped telephones, every movement of her family closely monitored and the horror of sitting up in the night with a double barrel gun to protect her children against stalkers.

The brutality of life in Nagaland, especially the brutalisation of many young men made her fear for the safety of her children. Her older daughter was traumatized on a short trip when their car was stopped and they were held for questioning by a group holding them at gunpoint. Her sister came within five meters of being shot when armed men began to indiscriminately fire at their human target, felling an innocent citizen. Her grown son was kidnapped for three days. After a trip to Norway, She received information about the International Cities of Refuge Network. In 2005, She took the offer of being put on a program as Tromsø's first Fribyforfatter and moved to Tromsø, Northern Norway in March 2005. The one year in a city of refuge, and freedom from a life where it was normal to hear gunshots in the night, every night, and be in constant fear of death has been very positive for her. She have written six books during her stay in Tromsø, of which two are being published in 2006. She continue to pray and dream of peace for her people and reflect it in her poetry.

At the same time, She is now able to admit and talk about the long-term damage to her people the years of protracted conflict have inflicted and She has slowly begun to address this in her new writings. While many of the writers in cities of refuge have experienced prison physically, her people and She have been living within an invisible prison for many years, denied freedom of expression, freedom to nationhood and most painfully, freedom to life itself. She is now thinking of new ways to help her people, especially the young, because this period away has from her homeland has to be utilized positively. And She is so grateful for the opportunity to have wider contacts and experience new avenues of empowerment. She feels that their only hope is in their young. Their futures should not be shadowed any longer by the conflict. She hopes She can sufficiently contribute to enabling them to move away from the bitterness and vicious cycle of killings and transcend the present gun-culture of her society. They deserve a better life than what we have known.