Election laws, rules. procedures: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Booth preparation

Trial runs

From: April 20, 2019: The Times of India

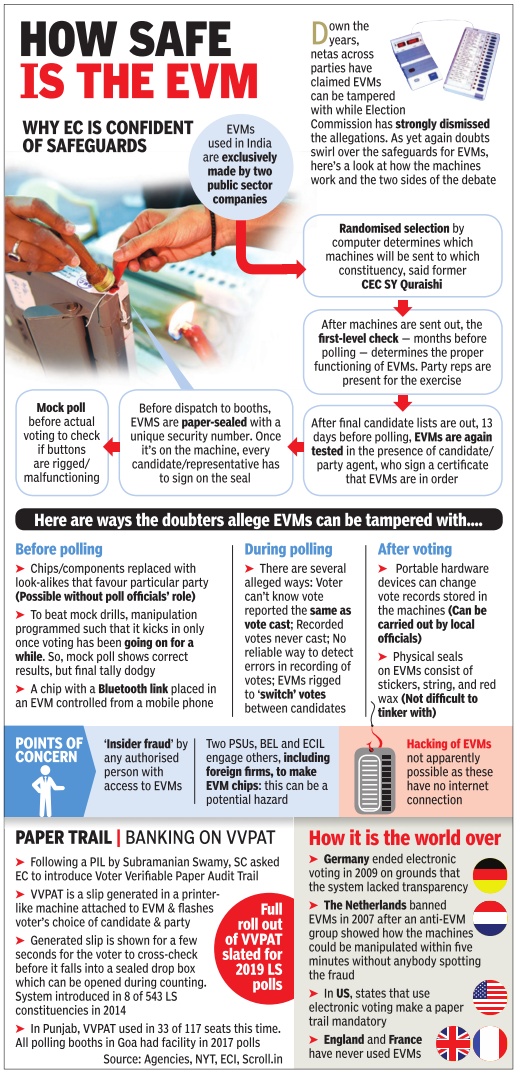

See graphic, 'Before voting begins at any booth, election officials must conduct mock polls. EVMs and VVPATs undergo three tests'

Court judgements

A constituency cannot go unrepresented beyond a time limit HC

Swati Deshpande, Dec 13, 2023: The Times of India

MUMBAI: The High Court for directed the Election Commission of India (ECI) to immediately hold by-elections for a parliamentary constituency seat that fell vacant this March in Pune. It held as “unacceptable’’ the reasons cited by the ECI and Centre as its ‘difficulties’ in holding the Pune by-poll, and noted how by-polls were held in other States for vacancies that arose later.

No amount of administrative inconvenience can undermine the statutory obligation of the ECI to hold a by-poll, nor is it the concern of the Commission to decide the effectiveness of the candidate for the full or remaining term, observed the Bombay high court.

Citizens have a right to be represented and the vacancy cannot remain unfilled for over a year, said the HC. The by-poll is for a Pune Lok Sabha constituency following the demise of Member of Parliament (MP) Girish Bapat on March 29, 2023.

“The EC is charged with the duty to conduct poll,’’ said the HC division bench of Justices Gautam Patel and Kamal Khata noting there are only two exceptions when a by-poll cannot be held within a time limit.

Kushal Mor, counsel for the petitioner, said as a voter of the Constituency, he has a right to be represented in the Lok Sabha. Mor said the ECI has a legal obligation to conduct the polls in compliance with Section 151A of the Representation of Peoples Act (ROPA). But questioning a reply to his RTI pleas of why the by-poll can’t be conducted –including the short stint for a newly elected MP-- Joshi had approached the HC for orders to direct the ECI to conduct the by-poll.

The section specifies a time limit within which a by-poll must be held subject to two exceptions. One is if remaining term is less than a year. If duration between onset of vacancy and end of term of that particular seat is less than a year then election need not be held but no defence is taken under this provision, at all, the HC noted. Besides, the vacancy arose in March and next LS elections are in June 2024, the HC said.

The other exception is if the Centre certifies it is difficult to hold a by-poll within that period.

The reasons or difficulties cited by the ECI in a ‘certificate’ of practical reasons, against holding the by-poll were that the term for the returning candidate would be short and hence ineffective.

One of the reasons that “borders on the bizarre’’ the HC said was when it was “solemnly told that whole of the ECI machinery is far too busy since March 29, 2023 in preparation for general elections to the Lok Sabha to be bothered with a Pune by poll’’ for a parliamentary seat. “We are told this is a genuine difficulty. Which it is not,’’ said Justice Patel as he dictated the order in open court in a petition filed by Sughosh Joshi, a Pune resident and voter. “The word ‘difficult’ –in the relevant provisions under the Representation of People’s Act-- is not to be read in this manner to mean some administrative inconvenience,’’ said the HC.

“It is simply unthinkable…It will amount to sabotaging the entire democratic framework,’’ said the bench, hoping that this is not what the ECI wants.

The ECI represented by advocate Pradeep Rajgopal opposing the petition said it should be filed in the form of a PIL not a writ petition.

The HC said, circumstances where a law and order situation exists can lead to not holding of a by-poll, “but to say due to pre-occupation can't hold by-poll is wholly unacceptable.’’

“The certificate… in this case is decidedly peculiar,’’ the HC observed. It said two things, one that the returned candidate would have a short tenure. “ It is not for ECI to adopt a sliding scale…unthinkable that several months will go past and that an entire constituency be told that the constituency might as well wait for the next elections… That is an abdication of constitutional duties which we cannot possibly accept,’’ Justice Patel dictated in the order.

“The EC is not concerned with whether the returned candidate will or will not be effective in the remaining term left. The ECI cannot decide the effectiveness of the candidate in the remaining term or five years term. The fundamental concern is only the right to representation. It cannot let a constituency remain unrepresented beyond the prescribed period,’’ the HC held.

THE PUNE VACANCY

March 29, 2023: Vacancy in Pune LS Constituency

August 11, 2023: ECI and Central government correspond on difficulty in holding the bypoll

August 23, 2023: Certificate issued on difficulty in holding Pune by-election

OTHER BY-POLLS in 2023

HC order notes By-elections held elsewhere: Vacancy in Lakshadweep on January 11, 2023 for disqualification; by-poll notification issue on January 18, 2023; by-pol eventually withheld as Kerala HC suspended the disqualification April 13, 2023: by-poll notified for LS seat in Jalandhar; Election date May 10, 2023

October 13, 2013 by poll notified for Nagaland Assembly (1 AC); poll date November 7

August 10, 2023: by poll notified for 7 legislative Assemblies of Jharkhand, Tripura, Kerala, West Bengal, UP and Uttarakhand

WHAT High Court Said:

· Neither administrative pre-occupation nor burden on exchequer are reasons to refuse or not conduct a bypoll.

· In any Parliamentary democracy government is by the people. They are the voice of the people.

· If representative is no more another must be elected.

· The people cannot go unrepresented. That is wholly unconstitutional and is an anathema to our constitutional structure · This is the reason why the SC held that provisions of ROPA oblige authorities under it to ensure that no constituency remains unrepresented for an indefinite period

Power of the EC have never been held to be exempt from judicial scrutiny. They are not, in words of SC, unbridled. Judicial review is always permissible.

·Voters cannot be denied this right. This is a protection conferred by Statute

WHAT NEXT

ECI counsel Pradeep Rajgopal: The ECI will be going to the Supreme Court to challenge the HC order to hold the by-poll immediately.

Petitioner’s counsel Kushal Mor: We are hopeful that the ECI issues the by-poll notification at the earliest now, so that the democratic process is complied with.

Declarations by poll aspirants

Election can be set aside, in case of false declaration in the nomination paper: SC

Says Voters Have Fundamental Right To Know About Contestants' Antecedents

The Supreme Court ruled on Tuesday that voters had a fundamental right to know about the educational background of people contesting polls and that election of a candidate could be set aside for making false declaration on educational qualifications in the nomination paper.

The ruling came when a bench of Justice A R Dave and Justice L Nageswara Rao quashed the election of Manipur Congress MLA, Mairembam Prithviraj, for falsely declaring in his nomination papers that he had an MBA degree.

The court held that the right to vote would be meaningless unless citizens were well-informed about the antecedents of candidates, in cluding their educational qualification. It said all information about a candidate contesting elections must be available in public domain as exposure to public scrutiny was one of the surest means to cleanse the democratic governing system and have competent legislators.

“This court held that the voter has a fundamental right to information about the contesting candidates.The voter has the choice to decide whether he should cast a vote in favour of a person involved in a criminal ca se. He also has a right to decide whether holding of an educational qualification or holding of property is relevant for electing a person to be his representative,“ the bench said.

“It is clear from the law laid down by this court that every voter has a fundamental right to know about the educational qualification of a candidate. It is also clear from the provisions of the Representation of the People Act, Rules and form 26 that there is a duty cast on the candidates to give correct in formation about their educational qualifications,“ the bench said.

The Congress MLA contended that there was a “clerical error“ on the part of his lawyer and agent who had filed the nomination papers in 2012 and pleaded to the court not to quash his election as the defect was not of substantial nature. Prithviraj had mentioned in the nomination papers that he had passed MBA in 2004 from Mysore University .

The bench, however, rejected his plea saying the election result was materially affected by the false declaration and it had to be quashed. The court noted that he had made the false declaration in the 2008 assembly election as well.

“The contention of the appellant that the declaration relating to his educatio nal qualification in the affidavit is a clerical error cannot be accepted. It is not an error committed once. Since 2008, he was making the statement that he has an MBA degree. The information provided by him in the affidavit filed in form 26 would amount to a false declaration.The said false declaration cannot be said to be a defect which is not substantial,“ the court said.

“It is no more res integra (issue not decided by court) that every candidate has to disclose his educational qualification to subserve the right to information of the voter. Having made a false declaration relating to his educational qualification, he cannot be permitted to contend that the declaration is not of a substantial character,“ the bench added.

SC: Poll aspirants must reveal income sources of self, kin

In a landmark verdict aimed at bringing more transparency and curbing money power in elections, the Supreme Court on Friday ruled that a candidate would have to make public the source of his income along with that of his spouse and dependants.

Holding that voters have a fundamental right to know all the relevant information about the candidates including their sources of income, a bench of Justices J Chelameswar and S Abdul Nazeer directed the Centre to amend the Conduct of Election Rules and Form 26 to incorporate the provision on declaration of source of income. It also directed that the candidates would also have to provide information regarding contracts with any government agency or PSUs, either by them or spouse and dependants.

“The voter is entitled to have all relevant information about the candidates at an election. The information regarding the sources of income of the candidates and their associates would in our opinion, certainly help the voter to make an informed choice of the candidate to represent the constituency in the legislature. It is, therefore, a part of their fundamental right,” the bench said.

“The enforcement of such a fundamental right needs no statutory sanction. This court and the HCs are authorised by the Constitution to give directions to the state and its instrumentalities for enforcement of Fundamental Rights,” the apex court said.

‘Undesirable trends seen in first 50 years’

The SC said the experience of the first 50 years of the functioning of democracy in the country disclosed some undesirable trends that have crept into its working and it was necessary to deal with it on urgent basis to maintain purity of the electoral process.

The bench made it clear

that non-disclosure of the information by candidates wou- ld constitute a corrupt practice falling under heading undue influence as defined under the Representation of People Act, and the election of the candidate could be quashed if elected.

“We direct that Rule 4A of the RULES and Form 26 appended to the RULES shall be suitably amended, requiring candidates and their associates to declare their sources of income,” the bench said.

Candidates need declare only children’s assets: HC

Aamir Khan2, Candidates need declare only kids’ assets: HC, November 2, 2018: The Times of India

A candidate in his election affidavit is not required to give details of assets and liabilities of any other dependent except the children, a Delhi court held while discharging AAP MLA Som Dutt. A BJP candidate, who lost to Dutt in 2015, had accused the AAP legislator of not listing his parents as dependants in his election affidavit both in 2013 and 2015 and later claiming medical reimbursement in his parents’ names after becoming an MLA.

Additional chief metropolitan magistrate, Samar Vishal, has based his order on a provision of Representation of People Act, 1951. The provision states that a candidate has to declare his or her movable and immovable property, besides those of the spouse and dependent children only. The term dependent children is also defined under law as sons and daughters who have no separate means of earning and are wholly dependent on the elected candidate for their livelihood.

The complainant, Praveen Jain, had alleged that when Dutt was elected as an MLA, he applied for a medical facility card from the Delhi government and mentioned the names of his parents as dependants.

Jain said that Dutt on one hand had not shown his parents as dependants in the election affidavit and kept mum on their assets, but after election, he obtained the medical card that mentioned his parents as dependants while claiming medical reimbursement of Rs 3,421 from the Delhi government. It was therefore alleged that Dutt had cheated the Delhi government by claiming reimbursement.

Responding to the allegation of reimbursement, judge Vishal observed that the only reason Jain had alleged that Dutt’s parents were not dependent was that they were not shown as dependents in the election affidavit. “This does not seem to be a legally sustainable allegation. The accused was not legally bound to mention about the dependency of his parents in election affidavit,” said the court.

In the court’s view, the purpose of an affidavit and a medical card are different and the term dependency may connote different meanings in two different documents. It found no allegation where Jain claimed that Dutt’s parents are otherwise not dependent on him or had an income that would have disqualified the parents from being dependent. “The only basis of assailing their dependency as mentioned in the medical card was the election affidavit, which is not sufficient to come to the conclusion that the parents were not dependent..,” the court held.

Election symbols

For history and evolution, see India: A political history, 1947 onwards

Symbols and the law

A party that loses its recognition doesn't lose symbol immediately, Jan 9, 2017: The Times of India

Under which law are the political parties allotted symbols for contesting elections?

According to the Constitution, the superintendence, direction and control of elections to the Parliament as well as states assemblies are vested in the Election Commission of India (EC).Through the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, the EC provides for specification, reservation, choice and allotment of symbols in the elections.

How are parties allotted symbols?

The 1968 order states that different symbols are to be allotted to candidates contesting in parliamentary as well as assembly elections. For this purpose, symbols are classified as reserved and free. A reserved symbol is a symbol reserved for a recognised political party for exclusive allotment to the candidates put up by the party . Symbols other than the reserved ones are classified as free symbols. For this and other such issues, the EC classifies parties as recognised and unrecognised. A recognised political party is further classified as a national or state party.

How is a party recognised as state party?

A political party becomes eligible for recognition as a state party if in the last election to the state assembly the party got 6% of the valid votes and at least two of its candidates were elected to the assembly .Parties getting 3% of the total seats or at least three MLAs elected -whichever is more -also get recognised as state parties. Similarly , parties getting 6% of the valid votes in the last Lok Sabha election and getting at least one MP elected from the state, or a party that has got one MP elected per 25 contesting candidates from the state will also get recognised as a state party. A party that had won 8% or higher of the valid votes in the last state or Lok Sabha election held in the state is also recognised as a state party.

What are the conditions for recognition as national party?

To qualify as a national party , candidates of a party must have got more than 6% of valid votes in the last assembly or Lok Sabha election in four or more states, and in addition get at least four MPs elected from these states. Parties that have won at least 2% of the total seats in the Lok Sabha with candidates getting elected from at least three states also qualify as a na tional party . In addition, any party that is recognised as a state party in at least four states also qualifies as a national party .

What are the rules followed while allotting symbols to parties?

A candidate set up by a national party at any election will be allotted the symbol reserved for the party. Similarly , a candidate of a party recognised as a state party in any particular state will be allotted the symbol reserved for that party in all constituencies in that state.

Can a state party be allotted its reserved symbol in a state in which it is not recognised?

Yes, if a political party recognised as a state party in some state or states sets up a candidate in any other state or UT, it can be allotted the symbol reserved for it in its state of recognition provided that symbol is not reserved for any recognised state party in that state. It is, however, up to the EC to grant such permission if the commission doesn't have a reasonable ground for refusing such application.Because of this law, Samajwadi Party cannot contest election in Andhra Pradesh on the cycle symbol, as it is reserved for TDP in that state.

What if a party loses its recognition?

A party that loses its recognition doesn't lose its symbol immediately .A party that is unrecognised in the present election but was a recognised national or state party not earlier than six years from the date of notification of the election can be allotted its reserved symbol. The extension in the use of symbol doesn't mean the extension of other facilities provided to recognised parties like free time on Doordarshan AIR, free supply of copies of electoral rolls and so on.

What will happen in case of a split in a party?

In case of a split, it is up to the EC to decide which faction represents the original party. The decision of the commission is binding on all rival sections. It is to be noted that recognition should be given to a party only on the basis of its own performance in elections and not because it is a splinter group of some other recognised party .

How symbols are allotted

Oct 13, 2022: The Times of India

How does EC compile/update its list of notified free symbols?

■The Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968 provides for specification, reservation, choice and allotment of symbols to political parties or candidates in a parliamentary or assembly election. The EC, being the implementing authority of this order, has been notifying the list of poll symbols since the first general election, including those ‘reserved’ for exclusive use by candidates put up by recognised national and state parties and the ‘free’ ones allotted to candidates of registered unrecognised parties or independent contestants. All poll symbols are the property of the EC. Care is taken while preparing the list of free symbols so that they don’t resemble one another or a reserved symbol. Free symbols depict easily identifiable items that the voter, even if illiterate, can rely on to distinguish one candidate from another. The free symbols list — as last updated on September 23, 2021 — had 197 entries. The list is dynamic in the sense that some free symbols become reserved when a new party gets enough votes or is elected to get recognised at the state level. Also, when a recognised party loses the status of a state party, its reserved symbol is not touched for a minimum of six years.

Thereafter, the reserved symbol can be declared free. A new party can pick three symbols from the free list or propose a symbol not on the list. The EC evaluates the proposed symbol names and design to ensure that they do not bear resemblance to any other symbol. The symbols order also restricts allotment of a symbol reserved for a state party in states where it is not recognised; or one that has a religious or communal connotation.

Lastly, the EC had consciously decided in 1991 not to notify or allot any symbol that depicts an animal or bird after complaints were received about the animal being subjected to cruelty during campaigns. In 2005, the EC stopped allotting party names along religious/communal lines. This is why the EC denied two fresh symbols to the factions of Shiv Sena — ‘trishul’ and ‘mace’ — in view of their religious connotation.

What are reserved symbols and how often is this list reviewed?

■The reserved symbols are held only by recognised national and state parties. A state party recognised in one or more states is entitled to use its reserved symbol not only in those states but, in case it decides to contest from states where it is not recognised, it will have first right to its reserved symbol in that state. This is why the reserved symbol of a recognised state party is not allotted for use by candidates of other parties even in states where it is not recognised. Like the ‘free’ symbols list, the list of reserved symbols is dynamic, with a party retaining its reserved symbol as long as it fulfils conditions of recognition at the national or state level.

Are there broad dos and don’ts on what constitutes a symbol?

■The EC picks free symbols that are items of common use and have a distinct shape and form so that they can help a voter distinguish between one candidate from another in a ballot paper.

Also, the symbols order restricts allotment of symbols with a religious or communal connotation. Unrecognised or new parties and independents seeking to contest an election can either pick from the list of free symbols or propose three new ones. In the first case, they can give names of 10 symbols, in order of preference, from the list of free symbols notified in the order. Alternatively, they can propose three new symbols till three months before expiry of the assembly term, in order of preference.

Why are animals and birds etc off the list?

■Prior to March 1991, the EC had specified a number of birds and animals as election symbols. However, it was represented to the EC in the late 1980s that such birds and animals were being subjected to cruelty by candidates. In one case, it was reported that hundreds of pigeons were slaughtered at public meetings by parties and candidates contesting against the party with the ‘pigeon’ symbol. In March 1991, the EC took a policy decision not to specify any animal or bird as a poll symbol. The list of free symbols notified on March 5, 1991 thus deleted pigeon, eagle, horse, zebra, goat and fish from the list of symbols.

As for parties with reserved symbols depicting animals, the EC requested them to voluntarily surrender them. While All India Forward Bloc (having lion as its symbol) and Mizo National Front (with a tiger symbol) agreed to the EC’s request, BSP, AGP and Sikkim Sangram Parishad (all allotted ‘elephant’ as symbol) and Maharashtrawadi Gomantak Party and Hill State People’s Democratic Party (allotted ‘lion’ as symbol) refused to give up, arguing that these depicted big animals that could not be subjected to cruelty.

Can a party seek change in its ‘reserved’ symbol?

■Yes, there have been many such instances. Both Congress and BJP symbols have changed on account of splits and mergers. Like, the Congress symbol was ‘a pair of bullocks carrying yoke’ between 1952 and 1969; after Indira Gandhi launched her own faction INC(R), the symbol was changed to ‘cow with suckling calf’ even as the ‘original’ Congress retained the ‘bullocks carrying yoke’ symbol. The current Congress symbol, ‘palm’, was used first in 1977.

Similarly, Bharatiya Jana Sangh’s (BJS) original election symbol from 1951 to 1977 was ‘oil lamp’. After BJS merged with Janata Party in 1977, the symbol changed to ‘farmer with plough’. BJP’s current symbol, lotus, was allotted in 1980 when former Jana Sangh members split with Janata Party to form BJP.

Can a free and reserved symbol resemble each other?

■Not only can there not be any resemblance between a free and reserved symbol but also between any of the poll symbols, whether free or reserved. For instance, the ‘mace’ symbol sought by Sena’s Eknath Shinde faction was found too similar to a ‘spinning top’ and its other preference, the ‘sun (without rays)’ symbol, was similar to free symbols like apple, cabbage or football. The idea behind keeping poll symbols distinct from one another in shape, size and form is to avoid any confusion in the mind of the voter when he/ she looks at the ballot paper.

Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs)

A Short History

Baijayant `Jay' Panda, A Short History Of EVMs , April 12, 2017: The Times of India

They are to paper ballots what motor vehicles are to horse drawn buggies

Alleging vote fraud through tampering of Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs) is a time-honoured tradition by losing candidates and parties in India. This tradition began right from the very first instance of the use of EVMs, when the Election Commission (EC) tried out a pilot project during the Kerala assembly elections in 1982.

In fact, Communist Party of India (CPI) candidate Sivan Pillai challenged the use of EVMs even before the election could be held, but the Kerala high court did not entertain him. However, the fun was only just beginning since Pillai, despite his apprehensions, ended up winning.

Thereupon it was the turn of the losing Congress party to challenge the use of EVMs and Pillai's victory , setting in motion a practice that has since become de rigueur for any self-respecting loser of an Indian election. Not all losing candidates go to court against EVMs, of course, but it has almost come to be considered bad form if the loser does not at least hold a press conference to denigrate them.

Ironically, in that first instance Congress actually prevailed. Though the HC turned down its argument that the Representation of the People Act (1951) and Conduct of Election Rules (1961) did not provide for EVMs, on appeal the Supreme Court then ruled in its favour in 1984.

In the resultant re-election conducted with traditional paper ballots, its candidate beat Pillai. Although of course that by itself was no proof against the veracity of EVMs, it has remained a beacon of hope for election losers over the decades.

In any event the 1984 SC ruling against EVMs had been on a legal technicality , and not about their fundamental suitability. That flaw was corrected by a 1988 amendment to the RoP Act, providing the legal framework for use of EVMs. In yet another ironic twist of history that was passed by a Parliament dominated by Congress, the only beneficiary of EVMs being set aside in favour of paper ballots.

The incorporation of machines, technology and automation for electoral voting goes back to at least 1892, when the first “lever voting machine“ was used in New York, after decades of relying on paper ballots. Punch-card voting machines were introduced in the US in the 1960s, and were still in use in Florida four decades later, when their malfunctioning helped make the 2000 presidential election controversial. The US also saw the first EVMs introduced in 1975.

Automation helps improve the efficiency and speed of voting and counting. But it is even more important in overcoming fraud, as well as aiding the crucial democratic requirement of secret ballots, both aspects being much more vulnerable in manual voting. Those, and the huge logistical challenges of paper ballots, were exactly the reasons why India's EC pushed for EVMs, after widespread malpractices in the 1970s.

Democracy in India has made much progress over the decades, with the rest of the world going from being cynical about its survival, to now treating it as a triumphant role model. And since at least the era of TN Seshan in the early 1990s, the EC has arguably become our most respected institution, not to mention helping several other nations run their elections better. EVMs have played a significant role in this transition, which has seen a drastic reduction in voting malpractices.

Those who demand a rollback to paper ballots are wrong, and forget why we moved on from them. After all, despite the real risks of road accidents, we don't abandon motor vehicles and go back to horse drawn carriages. Instead, we implement safety measures like speed limits, seat belts and helmets.

Of course, no technology is infallible, and credible allegations of EVM tampe ring must be taken seriously . Fortunately, the EC does. In 2009, it conducted a highly publicised exercise, asking petitioners to demonstrate tampering. None could.

Similarly , the Delhi HC in 2004 and Karnataka HC in 2005 had rejected petitions challenging EVMs, after exami ning scientific and technical experts.

In a case last month of an EVM allegedly yielding votes for only one party , the EC enquiry found that the allegation was untrue. Such quick responses by the EC to specific allegations, random audits, and public demonstrations are Uday Deb essential to reinforce EVMs' reliability.

But two aspects of EVMs in India remain works in progress that are important to further improve the electoral system. First, the EC's proposal to use “Totaliser“ machines to aggregate the vote counting of multiple EVMs has been stymied by litigation as well as the government's disagreement. This relates to the core of why secret ballots are crucial for democracy . Without it, voters at any particular booth stand the risk of being victimised for not voting for powerful interests.

Finally , a new generation of EVMs was developed in 2011 with a feature for Voter Verified Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT). As the name implies, these make it vastly easier to audit and verify the votes cast if challenged. After an SC judgment to deploy these EVMs by 2019, the EC has already commissioned 20,000 of them, and is awaiting funding for the rest.

That would take EVMs' trustworthi ness beyond reproach, but would sadly end 35 years of a gloriously entertaining tradition.

History, and court orders

When fear, anxiety and apprehension cloud the aspiration to gain the trust and votes of citizens to wrest back the reins of power during an unusually heated run-up to the high stakes general elections, it is but natural for some political leaders to see demons when there are none.

Someone wise had said politics and war made strange bed fellows. That is because victory at the hustings or in conflicts is the natural and sole consideration for any political or military alliance. But many a time, strategic and well calculated alliances go horribly wrong.

Though win and loss are two sides of the electoral coin, political parties attempt to keep a facesaving excuse alive even before votes are cast in case they taste defeat. Is attempt to discredit electronic voting machines (EVMs) one such excuse?

The Election Commission has deployed EVMs since 1998 by to register and compute votes. Prior to that, it was done through ballot papers. Often, the powerful, with money and muscle, pounded voters and ballots into submission through booth capturing.

Election petitions by defeated candidates before 1998 commonly listed booth capturing as the ground to allege electoral malpractice and seek annulment of the election. After 1998, many election petitions alleged tampering of EVMs.

EVMs had a humble beginning. Scientists of Bharat Electronics Ltd had initially developed these machines to weed out malpractices genetically present in conduct of trade union elections.

When these machines passed the tests in trade union elections with flying colours, it got the EC thinking about using them in general elections. It approached BEL to design EVMs suitable for Lok Sabha and assembly polls.

Alleged susceptibility of EVMs to tampering have been at the core of numerous challenges in courts. The Madras HC in AIADMK vs EC (April 10, 2001) had said, “There is no question of introducing any virus or bugs for the reason that the EVMs cannot be compared to personal computers. The programming in computers, as suggested, has no bearing with EVMs. The computer would have inherent limitations having connections through internet and by their very design, they may allow

alteration of the programmes, but the EVMs are independent units and the programme in EVM is entirely a different system.”

The Karnataka HC in Michael B Fernandes vs C K Jaffer Sharief (February 5, 2004) had said, “EVMs have been put in use in the last general elections and in the last assembly election in UP and other states. The practical wealth of experience has dispelled abundantly the theoretical unfounded apprehensions of the possible misuse. Cost-wise also, use of EVMs is economical. Traditional manual method involves huge cost towards printing shares and counting expenses.”

The Bombay HC in Banwarilal vs Vilas Muttemwar (October 21, 2005) had said, “Next question is whether EVMs were susceptible for rigging nd whether rigging could have been done by using devices which could be operated from a remote distance, and without actual access to either the strong room or to the EVMs?”

The election petitioner had produced two technical experts who attempted to demonstrate that EVMs were hackable. But the HC after examining the evidence said, “The evidence of the petitioner’s witnesses does not inspire any confidence to prove the fact that EVMs are temperable or, on facts, that those were tampered with.”

After several judicial scrutinies established non-hackable nature of EVMs, the SC in 2013 gave two judgments — one, on a PIL by People’s Union for Civil Liberties and the other on an appeal filed by Subramanian Swamy. It had, respectively, ordered EC to make provision for ‘none of the above’ (NOTA) option and voter verifiable paper audit trail (VVPAT) with EVMs, to give full meaning to voters’ freedom of expression and enhance sanctity of votes.

But some political parties continue to adopt an unusual practice. They do not utter a word of praise for EVMs when their candidates emerge victorious in a neck-toneck contest but refrain from casting aspersions on these machines. But when they lose or apprehend loss, they revert to their usual facesaving tactics of discrediting EVMs even before the vote is cast.

Such tactics, in a way, discredit the scientists who devised EVMs. For, the Karnataka high court in Michael B Fernandes case had recorded, “It has come in evidence of the witness that countries like Singapore, Malaysia and USA are interacting with BEL for supply of EVMs suitable for their election requirements.” What is worse about such discrediting tactics is that it tends to undermine the intelligence of voters and their choices exercised through EVMs.

Political parties will do well to remember what Winston Churchill had said in the House of Commons on October 41, 1944, “At the bottom of all the tributes paid to democracy is the little man, walking into the little booth, with a little pencil, making a little cross on a little bit of paper… no amount of rhetoric or voluminous discussion can possibly diminish the overwhelming importance of that point.”

In Mohinder Singh Gill case [1978 (3) SCR 272], the SC had added its view to Churchill’s and said, “If we may add, the little, large Indian shall not be hijacked from the course of free and fair elections by mob muscle methods, or subtle perversion of discretion by men dressed in little, brief authority. For ‘be you ever so high, the law is above you’.”

We suggest political parties to trust ‘the little, large Indians’ ability to walk into the little booths, and press a little button on the little machines to make their choice as to who should hold the reins of power. With EVMs having proved their mettle in election after election, political parties will do well to focus on their strengths than attempt resurrecting paper ballots, which were susceptible to booth capturing by the mighty.

1980: Supreme Court junked the first EVM experiment in Kerala

Ajoy Sinha Karpuram, April 28, 2024: The Indian Express

The Supreme Court on April 26 put the stamp of its unequivocal approval on electronic voting machines (EVMs). Forty years ago, when a voting machine was first used at the Parur Assembly constituency in Kerala, the court had set aside the election and ordered a repoll in 50 of the 85 polling stations.

In 1982, the Election Commission of India (ECI) announced that the machine would be used as a pilot project in 50 out of 84 polling stations in the Parur constituency during that year’s Assembly elections in Kerala. The central government had not sanctioned the use of the machines, but the ECI used its constitutional powers under Article 324, which gives it the power of “superintendence, direction, and control” over elections.

In the result declared on May 20, 1982, Sivan Pillai (CPI) beat Ambat Chacko Jose (Cong) by 123 votes. Pillai got 30,450 votes, 19,182 of which were cast using voting machines.

Jose challenged the result in the trial court, which upheld the validity of voting via machines, and the result of the election. Jose appealed to the Supreme Court, where a Bench comprising Justices Murtaza Fazal Ali, Appajee Varadarajan, and Ranganath Misra heard the case.

What top court said

The ECI argued that its powers under Article 324 would supersede any Act of Parliament, and if there was conflict between the law and the ECI’s powers, the law would yield to the Commission.

In response, Justice Fazal Ali would write, “This is a very attractive argument but on a closer scrutiny and deeper deliberation…it is not possible to read into Art. 324 such a wide and uncanalised power”. The Bench unanimously held that introducing voting machines was a legislative power that only Parliament and state legislatures could exercise (Articles 326 and 327), not the ECI.

The ECI also relied on Section 59 of The Representation of the People Act, 1951 and Rule 49 of The Conduct of Elections Rules, 1961. Section 59 says “votes shall be given by ballot in such manner as may be prescribed”, and Rule states the ECI can publish a notification to “direct that the method of voting by ballot shall be followed…at such polling stations as may be specified in the notification”.

However, the court held that the “manner as may be prescribed” was by using ballot paper, not voting machines. The court also held that the word ‘ballot’ in its “strict sense” would not include voting through voting machines, and noted that the Centre as a rule-making authority “was not prepared to switch over to the system of voting by machines”.

The court observed that “if the mechanical process is adopted, full and proper training will have to be given to the voters which will take quite some time”.

Aftermath of ruling

A byelection was held on May 22, 1984, which Jose won. But the idea of voting machines would not be abandoned.

In 1988, the election law was amended to insert Section 61A, which allowed the ECI to specify the constituencies where votes would be cast and recorded by voting machines.

A decade later, EVMs were used at 16 Assembly seats in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Delhi. This was expanded to 46 Lok Sabha seats in 1999 and, in 2001, state elections in Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Puducherry, and West Bengal were entirely conducted using EVMs.

By the 2004 Lok Sabha election, EVMs had completely replaced ballot papers at all 543 seats.

Apprehensions vs. ECI’s rebuttals

From: Bharti Jain, EC plans presentation for oppn on ‘safe EVMs’ today, February 4, 2019: The Times of India

Having consistently reposed its faith in EVMs, the Election Commission, which will meet leaders of several opposition parties on Monday, will once again try and clear their misgivings and educate them on the safeguards that make these machines completely tamper-proof.

Sources said the commission will share a detailed presentation on EVMs with the opposition leaders, seeking to highlight the distinction between defective EVMs and tampering of EVMs.

According to an EC functionary, while 1-2% of EVMs on an average develop defects during polls and are replaced with fully functional units, no incident of EVM tampering has ever been detected or proved. The EC maintains that going back to ballot paper would be a retrograde step when technology was being used for most transactions. Also, when ballots were used, 2,000 invalid votes were recorded in each constituency on an average, vote stuffing was easy and gave candidates with muscle power undue advantage, and counting of ballots was prone to delay and errors.

“All such defective EVMs are promptly replaced with good machines. No wrong vote is ever recorded even in a defective EVM,” a senior officer said.

How safe is the Electronic Voting Machine in India

See graphic:

How safe is the Electronic Voting Machine in India?

Economics and profits of EVM manufacture

Even as opposition parties demand a return to ballot papers for the general election ahead, Electronics Corporation of India Limited (ECIL) — the manufacturer of EVMs — is set to record the highest revenue in its 53-year history.

Sources told TOI that apart from new orders for EVMs and VVPATs, the entire lot of old EVMs have been replaced with the M3 version, which has only added to ECIL’s revenue. In 2017-18 the gross turnover of ECIL was Rs 1,275 crore. In the 2018-19 financial year, the Election Commission gave orders worth Rs 1,800 crore for EVMs and VVPATs, which is likely to boost ECIL’s turnover to Rs 2,400 crore.

ECIL also makes electronic fuses for the Army, legacy military radios, jammers, and passive autocatalytic recombiner devices for nuclear power plants. The annual report of ECIL for 2017-18 says it has a target of Rs 1,800 crore in turnover in its MoU with the Department of Atomic Energy for 2018-19.

An ECIL official told TOI: “The bulk orders are for EVMs and VVPATs for the general and state elections to be held in 2019. Our turnover will touch Rs 2,600 crore this year. As the old machines are replaced with the new version the revenue has increased.”

Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL), Bangalore, is another major manufacturer of EVMs and VVPATs. Recently, BEL products were used in the Telangana assembly elections.

Rear Admiral Sanjay Chaubey (Retired), chairman and managing director of ECIL, sated in his report for the previous financial year: “The Company has augmented the manufacturing facility in terms of infrastructure and machinery to meet the current requirement of EVMs and VVPATs of ECI for the forthcoming General Elections as per schedule.”

VVPAT (Voter Verified Paper Audit Trail): An alternative?

Srinivasan Ramani, March 31, 2019: The Hindu

some features

From: Srinivasan Ramani, March 31, 2019: The Hindu

Another level of verification

While the introduction of EVMs in place of paper ballots increased people's and parties' trust in the polling process, some parties, in October 2010, asked the Election Commission to bring in a mechanism to verify the votes cast

The EC delegated the issue to its technical committee to gather the design requirements for the VVPAT system

In 2011, the Electronics Corporation of India Limited and Bharat Electronics Limited designed a prototype and demonstrated it to the committee

Mock polls were held in such places as Cherrapunji, Ladakh, Thiruvananthapuram and Jaisalmer for a field trial of the VVPAT

In 2013, the Conduct of Elections Rules, 1961, were amended to use VVPATs along with EVMs

How will the Election Commission ensure a tamper-proof counting process in the coming Lok Sabha election?

The story so far: The Election Commission indicated to the Supreme Court on Friday that if the 50% Voter Verified Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT) slip verification is carried out, it will delay counting by six days. Twenty-one Opposition parties had moved the Supreme Court against the EC’s guideline that VVPAT counting would take place only in one polling station in each Assembly segment in the coming Lok Sabha election.

What is the VVPAT and how does it function?

The Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trail device is an add-on connected to the Electronic Voting Machine. It allows voters to verify if their vote has indeed gone to the intended candidate by leaving a paper trail of the vote cast. After the voter casts his or her mandate by pressing a button related on the ballot machine (next to the symbol of the chosen party), the VVPAT connected to it prints a slip containing the poll symbol and the name of the candidate. The slip is visible to the voter from a glass case in the VVPAT for a total of seven seconds and the voter can verify if the mandate that s/he has cast has been registered correctly. After this time, it is cut and dropped into the drop box in the VVPAT and a beep is heard, indicating the vote has been recorded.

Prior to voting, the VVPAT unit is calibrated to ensure that the button pressed on the ballot unit of the EVM is reflected correctly on the printed slips by the VVPAT. The presence of the slips that correspond to voter choice on the EVM helps retain a paper trail for the votes and makes it possible for the returning officer to corroborate machine readings of the vote. The VVPAT machines can be accessed only by polling officers. The units are sealed and can be opened during counting by the returning officer if there’s a contingency. The VVPAT has been a universal presence in all EVMs in the Assembly elections from mid-2017. Only a few VVPAT machines are tallied to account for the accuracy of the EVM. Currently slips in one randomly chosen VVPAT machine per Assembly constituency are counted manually to tally with the EVM generated count. The EC has stated that VVPAT recounts have recorded 100% accuracy wherever it has been deployed in Assembly elections.

'Why is the VVPAT necessary?

The EC began to introduce EVMs on an experimental basis in 1998, and it was deployed across all State elections after 2001. EVMs have made a significant impact on Indian elections. Prior to the deployment of EVMs, elections were held with ballot papers. In some States, the election process was vitiated by rigging, stuffing of ballot boxes and intimidation of voters. Besides this, ballot paper-based voting resulted in the casting of a high number of invalid votes — voters wrongly registering their choices instead of placing seals, and so on.

The EVMs allowed for elimination of invalid votes as the voting process was made easier — registering the vote by pressing a button. It also allowed for a quicker and easier tallying of votes. Cumulatively, the tallying and elimination of invalid votes reduced the scope for human error. Secondly, the EVMs made it difficult to commit malpractices as they allowed for only five votes to be registered every minute, discouraging mass rigging of the scale that was seen in earlier days when ballot papers were used. That said, there have been questions raised about the security of the EVMs and whether they can be manipulated and tampered with. The EC has addressed the possibility of tampering by gradually introducing newer security and monitoring features, upgrading EVMs with technological features that allow for dynamic coding and time-stamping of operations on ballot units and later, features such as tamper-detection and self-diagnostics. Furthermore, there are administrative steps that prevent EVMs from being stolen and tampered with. The introduction of the VVPAT adds another layer of accountability to the electoral process. The recount rules out any EVM tampering, despite the safeguards, through an “insider fraud” by EC officials or EVM manufacturers.

What problems have been encountered?

In the initial phase of VVPAT implementation in the Lok Sabha by-elections in States such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Maharashtra and the Assembly election in Karnataka, there was a high rate of failure of VVPAT machines due to manufacturing glitches. In the Lok Sabha by-elections in 2017, the rate of VVPAT replacement, owing to glitches, was more than 15%, higher than the acceptable rates of failure (1-2%). In Karnataka, the failure and replacement rate was 4.3%. Coincidentally, the failure rate of the EVM unit (excluding the VVPAT) was very low. These glitches also caused severe disruptions to polling. To account for failure rates, the EC has tried to provide back-up machines to allow for swift replacement. The EC admitted later that the machines had high failure rates owing to hardware issues that occurred during the transport of EVMs and their exposure to extreme weather conditions. It sought to correct these problems by repairing components related to the printing spool of the VVPAT machines. The deployment of many corrected machines in the Assembly elections held recently in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh resulted in much reduced replacement rates (close to 2.5% in Madhya Pradesh and 1.9% in Chhattisgarh). This suggests that the EC is relatively better prepared to handle VVPAT-related glitches in the upcoming Lok Sabha election, where the VVPATs will be deployed in nearly 10.5 lakh polling stations nationwide.

Is the current rate of VVPAT recounts enough?

Political parties, primarily of the Opposition, have demanded a greater VVPAT recount than the one booth per Assembly/Lok Sabha constituency rule that is now in place. The EC responded to a plea by the Opposition parties in the Supreme Court that there was a need for 50% VVPAT recount, saying such an exercise would delay the counting by six days. Statistically speaking, it does not require a 50% sample to adequately match VVPAT tallies with those of EVMs. The Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata, has presented a report on possible and appropriate VVPAT counts to the EC, in which it said a sample verification of 479 EVMs and VVPATs of a total 10.35 lakh machines would bring the level of confidence in the process to 99.9936%. The logic behind counting only one booth per constituency in each State stems from the understanding that there are nearly 10.35 lakh polling stations and 4,125 Assembly constituencies in the country.

By counting the slips in at least one VVPAT in each Assembly constituency, the EC argues, a relatively high sample size of the EVMs (0.5%) is verified. Critics have argued that this sample size is not enough to statistically select a potentially tampered EVM within a high confidence level and adjusting for a small margin of error (less than 2%) as the unit of selection must be EVMs in each State rather than the entire country as a whole. One suggestion, by the former bureaucrat Ashok Vardhan Shetty, is for adjusting the VVPAT counting process to factor in the size of the State, population of the constituency and turnout to account for a higher confidence level and a low margin of error. This would entail the certain tallying of more than one VVPAT per constituency, in fact close to 30 per constituency in smaller States and less than five per constituency for larger States. The Supreme Court has said the EC must increase the VVPAT count to more than the current number.

SC, 2019: Count VVPAT slips of 5 booths in each assembly seat

Dhananjay Mahapatra, April 9, 2019: The Times of India

From: Dhananjay Mahapatra, April 9, 2019: The Times of India

Order To EC Will Delay Results By Four Hours

With opposition parties persistently calling for an enhanced paper trail count, the Supreme Court on Monday ordered the Election Commission to increase by five times the number of EVMs

whose vote count must be matched with VVPAT slips in each assembly segment.

This could, on average, mean 35-40 VVPAT counts per parliamentary constituency, and delay results in elections by around four hours, raising the possibility of formal declaration of winners and losers coming late into the night of May 23 when counting of votes is scheduled.

Though leaders of 21 non-NDA parties failed to convince the SC of the need to count VVPAT slips of 50% of EVMs in the Lok Sabha elections, their counsel A M Singhvi could claim moral victory as he succeeded in getting the EC to change its procedure of counting VVPAT slips of one randomly selected EVM per assembly segment.

2019/ Biggest EVM-VVPAT mismatch was 34 votes

Bharti Jain, July 24, 2019: The Times of India

The largest difference in VVPAT and EVM count in the eight cases of mismatch found in the recent general elections was in Shillong parliamentary constituency of Meghalaya. Two polling stations for which VVPAT slips were matched with the EVM count in Shillong showed up anomalies, one amounting to four slips and the other 34 slips.

A polling station in Rajampet in Andhra Pradesh showed a mismatch of seven between the VVPAT and EVM counts. The EVM and VVPAT count did not throw up a perfect match in Shimla constituency where a polling station showed a difference of one vote. In Rajasthan, the EVM tally differed from the VVPAT count by one vote in a polling station each in Chittorgarh and Pali constituencies. Manipur reported two cases of mismatch between VVPAT and EVM count. A polling station in Inner Manipur showed a difference of one vote while another polling station in Outer Manipur showed a gap of two.

Election Commission officials, who are determined to examine reasons for the mismatches, are yet to get access to the said EVMs and VVPATs as state chief electoral officers are still obtaining a list of election petitions filed in the respective high courts.

“Our information so far is that no election petition has been filed challenging the result in constituencies where the eight cases of mismatch were found. So, we should get to examine the EVMs and VVPATs soon,” an EC functionary told TOI.

Preliminary assessment by the EC of the eight mismatches — which amounted to barely 0.0004% of the total 20,687 random EVMs for which VVPAT slips were counted and too minor to make any difference to the result — attributed them to human error.

An official explained that in Shillong, where VVPAT slips were 34 less than the EVM count, and even in Rajampet where the mismatch was of seven votes, the discrepancy was possibly due to failure on part of the presiding officer to delete mock poll data, notwithstanding EC’s repeated instructions to do so.

The officer added that while a recount was usually taken in the event of EVM count not tallying with the number of VVPAT slips, it was possible that the same was dispensed with as the candidate/ agents did not insist on it, knowing it would not alter the result.

As for the difference of 1-2 slips, it is suspected to be an outcome of bundling of VVPAT slips. “The bundled slips may still be counted as one in a recount,” an EC official said.

2024: SC attests to integrity of EVMs; ‘possibility of hacking unfounded’

Amit Anand Choudhary, April 27, 2024: The Times of India

From: Amit Anand Choudhary, April 27, 2024: The Times of India

NEW DELHI: Supreme Court dismissed doubts about hacking and manipulation of Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs), termed pleas for return to the paper ballot system as “foible and unsound” and rejected the prayer for giving voters physical access to VVPAT slips, and for 100% counting of paper slips.

The court was unequivocal in attesting to the integrity of the machines, saying the possibility of hacking or tampering with EVM to tutor/favour results was unfounded.

“Accordingly, the suspicion that EVMs can be configured/manipulated for repeated or wrong recording of vote(s) to favour a particular candidate should be rejected,” it said.The verdict marked a big blow to the high-wattage campaign against EVMs, especially since 2014 when BJP under Narendra Modi pulled off a stunning victory.

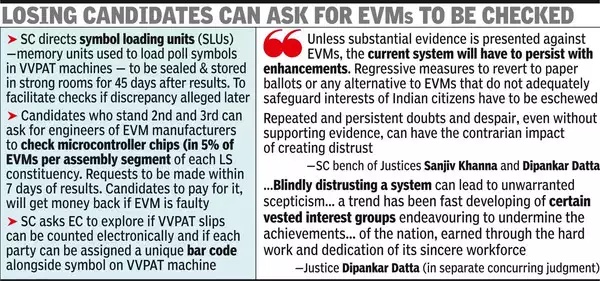

A bench of Justices Sanjiv Khanna and Dipankar Datta, however, passed directions to further strengthen the integrity of the system and ordered that like EVMs, the symbol loading units shall be sealed and secured after completion of symbol loading process in the VVPATs (Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trail). It also granted an option to the runner-up and the candidate finishing third to get burnt memory/microcontroller in 5% of EVMs — control unit, ballot unit and VVPAT unit — per assembly constituency/assembly segment of a parliamentary constituency checked and verified after the announcement of results for any tampering.

The apex court examined threadbare the administrative and technical safeguards in EVMs and concluded that there was no substance in the allegations. “Repeated and persistent doubts and despair, even without supporting evidence, can have the contrarian impact of creating distrust. This can reduce citizen participation and confidence in elections, essential for a healthy and robust democracy. Unfounded challenges may actually reveal perceptions and predispositions, whereas this court, as an arbiter and adjudicator of disputes and challenges, must render decisions on facts based on evidence and data,” the bench said.

Noting that the microcontroller used in EVM had one-time programmable memory and was unalterable once burned, the bench said, “To us, it is apparent that a number of safeguards and protocols with stringent checks have been put in place. Data and figures do not indicate artifice and deceit. Reprogramming by flashing, even if we assume is remotely possible, is inhibited by the strict control and checks put in place. Imagination and suppositions should not lead us to hypothesise a wrongdoing without any basis or facts. The credibility of the EC and integrity of the electoral process earned over years cannot be chaffed and over-ridden by baroque contemplations and speculations.”

Noting the almost flawless data on functioning of EVMs and VVPATs, the bench said there was only one case of mismatch, that too because of human error in 2019 when data of the mock poll was not deleted in an EVM. It added that voters had a right to question the working of the system but they must exercise caution while doing so.

On the plea seeking 100% counting of VVPAT slips and right of voters to physical access to the slips, the bench said, “While we acknowledge the fundamental right of voters to ensure their vote is accurately recorded and counted, the same cannot be equated with the right to get physical access to the slips.” It said giving physical access to VVPAT slips to voters was “problematic and impractical which will lead to misuse, malpractices and disputes”.

“We are not inclined to modify the directions to increase the number of VVPAT undergoing slip count for several reasons. First, it will increase the time for counting and delay declaration of results. The manpower required would have to be doubled. Manual counting is prone to human errors and may lead to deliberate mischief. Manual intervention in counting can also create multiple charges of manipulation of results. Further, the data and the results do not indicate any need to increase the number of VVPAT units subjected to manual counting,” it said.

The bench, however, asked EC to explore the possibility of deploying machines to count VVPAT slips and also barcoding the symbols loaded in VVPATs which would be helpful in machine counting.

The court was also unambiguous in ruling out a return to paper ballot which was junked following allegations of largescale malpractices.

“We must reject as foible and unsound the submission to return to the ballot paper system. The weakness of the ballot paper system is well-known and documented. In the Indian context, keeping in view the vast size of the Indian electorate of nearly 97 crore, the number of candidates who contest the elections, the number of polling booths where voting is held, and the problems faced with ballot papers, we would be undoing the electoral reforms by directing reintroduction of ballot papers. EVMs offer significant advantages. They have effectively eliminated booth capturing by restricting the rate of vote casting to votes per minute, thereby prolonging the time needed and thus check insertion of bogus votes,” the bench said.

E-postal ballot (online voting)

Allowed for armed forces/ 2016

E-postal ballot allowed for armed forces, Oct 25 2016 : The Times of India

The government has amended electoral rules to allow postal ballots to be sent electronically to the armed forces personnel, cutting delays experienced with their two-way transmission through post.

This would mean that armed forces personnel can now download the blank postal ballot sent to them electronically , mark their preference and post the filled-up ballot back to their respective returning officers.Two-way electronic transmission was not recommended by the Election Commission for security and secrecy reasons.

The armed forces personnel serving in remote and border areas would be greatly benefited since the present system of two-way transmission of ballot paper by the postal services has not been able to meet the expectations of the service voters. The issue had earlier come up before the Supreme Court where it was pleaded that an effective mechanism be created for armed forces personnel and their families to exercise their right to vote easily.

Independent candidates

… need 10 proposers

An Independent Needs 10 Backers Before the candidate gets the votes, s/he has to first get a voter, or voters (as the case may be), of that constituency to endorse the candidature at the time of filing of nomination. Candidates for a recognised national or state party need only one proposer. But an Independent or a candidate from a registered unrecognised party needs 10 proposers. An Independent may even submit a nomination with more than 10 proposers. Candidates of a state party recognised in another state but not in the state concerned, too, must have 10 proposers

Manifestoes, promises

False promises

Rohan Dua, Don't promise the moon to voters: EC, Nov 01 2016 : The Times of India

The election commission has decided to crack down on parties that go overboard with their manifesto promises. Officials will soon start vetting manifestos for the 2017 assembly polls in Punjab and UP.

Punitive action could be as harsh as withdrawing a party's symbol if it promises the moon without giving an affidavit on a stamp paper to the commission.

The decision was taken at a meeting on September 23, according to an internal note accessed by TOI. “... it is expected that manifestos reflect the rationale for the promises and broadly indicate the ways and means to meet the financial requirements for it. Trust of voters should be sought only on promises which can be fulfilled,“ it reads.

In 2012, the Shiromani Akali Dal had promised laptops to class 12 students but later backtracked because of a Rs 1.25 lakh crore debt.

Parties cannot be stopped from making promises: SC, 2023

Oct 7, 2023: The Times of India

NEW DELHI: The Supreme Court on Friday said it could not control political parties from making all kinds of election-eve promises but decided to seek responses from Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, the Centre and the Election Commission on a PIL that alleged that irrational cash doles announced by chief ministers of poll-bound states were pushing these states into financial crises.

"Before elections, all kinds of promises are made. We can't control it," said a three-judge bench led by Chief Justice of India D Y Chandrachud when a PIL filed by Bhattulal Jain came up for hearing. Jain's counsel said that cash doles promised by the CM of Madhya Pradesh, which is facing financial constraints, would put the state in a precarious condition financially and the burden would be passed on to the taxpayers after the polls.

Unaware of Jain's recent unsuccessful attempt before the Madhya Pradesh high court on this issue, the CJI asked petitioner's counsel why he had approached the SC directly without moving the HC. The counsel then said that Rajasthan chief minister had also announced similar cash doles.

The bench then decided to issue notice to the two states, the Union government and the EC, and tagged the petition with the pending PIL of Ashwini Upadhyay, who has sought a direction to the EC to frame guidelines to rein in parties from making election-eve promises for irrational freebies without quantifying the cost of such promises to the exchequer and future burden on taxpayers.

Cash doles, as part of poll eve strategy or otherwise, is nothing new and it has been prevalent in states ruled by both NDA and opposition INDIA alliance parties.

Minimum age of candidates

SC: We do not have the power to change age limit

‘Can’t take call on min age to contest’

TIMES NEWS NETWORK

From the archives of The Times of India 2007, 2009

New Delhi: Why not change the age limit for contesting the Lok Sabha and assembly elections to 21 years from the stipulated 25 years, when the age of voting has been reduced from 21 years to 18 years?

On Monday, this question from a PIL by one Kumar Gaurav left a Supreme Court bench comprising Chief Justice K G Balakrishnan and justices R V Raveendran and Deepak Verma thinking for a while. But, it countered the petitioner by asking: “What is the hurry? Why not have some experience of politics before entering the fray?” Well the counsel for the petitioner was not to be deterred and said it was the people’s fundamental right to choose a profession and politics has become one. He said most of the countries around the world have reduced the age limit for people’s representatives to 18 years and India should follow suit.

The bench said: “But this would require amendments to several Articles of the Constitution which prescribe the age limit. Can the SC do it? We do not have powers to reduce the minimum age stipulated for persons to contest Lok Sabha or assembly elections.”

Minimum education qualification for contestants

SC disagrees

The Times of India, September 22, 2015

AmitAnand Choudhary

SC frowns on edu bar for Haryana poll

The Supreme Court expressed concern over recent laws framed by some state governments fixing minimum education qualification for people to contest local body elections and questioned its validity as it would bar majority of the population from the contest.

“Let's settle the issue as it would be followed across the country ,“ a bench of Justices J Chelameswar and A M Sapre said while hearing a plea questioning the validity of a law passed in Haryana mandating educational qualification -Class 10 for men, Class 8 for women and Class 5 for Dalits -for those contesting panchayat polls. Attorney general Mukul Rohatgi, appearing for the state, contend ed that it was a progressive law and the SC should not interfere. The bench then referred to Article 326 of the Constitution, which lays down the grounds for disqualification, and asked, “Can a legislature prescribe other ground for disqualification?

It needs to be examined.“

After a brief hearing, the bench said it would allow the election process if the state agreed to drop education qualification criteria and asked the AG to take instructions from the government.

Voter has right to know candidate’s qualification: SC

The Hindu, November 4, 2016

Every voter has a fundamental right to know the educational qualification of a candidate, who has a duty not to lie about his or her academic past, the Supreme Court has held.

“Every voter has a fundamental right to know about the educational qualification of a candidate. There is a duty cast on the candidates to give correct information about their educational qualifications,” a Bench of Justices Anil R. Dave and L. Nageswara Rao held in a recent judgment.

The verdict came on appeals filed by Mairembam Prithviraj alias Prithviraj Singh and Pukhrem Sharatchandra Singh against each other challenging the judgment of the Manipur High Court. The HC had declared as “void” the election of Mr. Prithviraj in the 2012 polls on an NCP ticket against Congress nominee Mr. Sharatchandra from the Moirang Assembly seat in Manipur. It was alleged that Mr. Prithviraj, in his nomination papers, had said he was an MBA, which was found to be incorrect.

Upholding the HC verdict, Justice Rao said the apex court was not “in dispute that the Appellant did not study MBA in Mysore University” and the plea that it was a “clerical error” could not be accepted. “Since 2008, the Appellant was making the statement that he has an MBA degree. The information provided by him in the affidavit filed in Form 26 would amount to a false declaration. The said false declaration cannot be said to be a defect which is not substantial ... ,” the judgment said.

Model Code of Conduct

Definition

What is covered under the Model Code of Conduct for elections?

What is the philosophy behind the Model Code of Conduct?

The Model Code of Conduct (MCC) is a consensus document. In other words, political parties have themselves agreed to keep their conduct during elections in check, and to work within the Code. The philosophy behind the MCC is that parties and candidates should show respect for their opponents, criticise their policies and programmes constructively, and not resort to mudslinging and personal attacks. The MCC is intended to help the poll campaign maintain high standards of public morality and provide a level playing field for all parties and candidates.

Adherence to the Code is most important for the government or party in power, because it is they who can skew the level playing field by taking decisions that can help them in the elections. At the time of the Lok Sabha elections, both the Union and state governments are covered under the MCC.

How has the MCC evolved over the years?

Kerala was the first state to adopt a code of conduct for elections. In 1960, ahead of the Assembly elections, the state administration prepared a draft code that covered important aspects of electioneering such as processions, political rallies, and speeches. The experiment was successful, and the Election Commission decided to emulate Kerala’s example and circulate the draft among all recognised parties and state governments for the Lok Sabha elections of 1962. However, it was only in 1974, just before the mid-term general elections, that the EC released a formal Model Code of Conduct. This Code was also circulated during parliamentary elections of 1977.

Until this time, the MCC was meant to guide the conduct of political parties and candidates only. However, on September 12, 1979, at a meeting of all political parties, the Commission was apprised of the misuse of official machinery by parties in power. The Commission was told that ruling parties monopolised public spaces, making it difficult for others to hold meetings. There were also examples of the party in power publishing advertisements at the cost of the public exchequer to influence voters. At this meeting, political parties urged the Commission to change the Code. So the EC, just before the 1979 Lok Sabha elections, released a revised Model Code with seven parts, with one part devoted to the party in power and what it could and could not do once elections were announced.

The MCC has been revised on several occasions since then. The last time this happened was in 2014, when the Commission introduced Part VIII on manifestos, pursuant to the directions of the Supreme Court.

Part I deals with general precepts of good behaviour expected from candidates and political parties. Parts II and III focus on public meetings and processions. Parts IV and V describe how political parties and candidates should conduct themselves on the day of polling and at the polling booths.

Part VI is about the authority appointed by the EC to receive complaints on violations of the MCC. Part VII is on the party in power.

The evolution of the code, till 2024 March

March 16, 2024: The Indian Express

The MCC is a consensus document. This means that political parties have themselves agreed to keep their conduct during elections in check, and to work within the Code. The philosophy behind the MCC is that parties and candidates should show respect for their opponents, criticise their policies and programmes constructively, and not resort to mudslinging and personal attacks.

The MCC forbids ministers (of the central and state governments) from using official machinery for election work and from combining official visits with electioneering. Advertisements extolling the work of the incumbent government using public money are to be avoided. The government cannot announce any financial grants, promise construction of roads or other facilities, and make any ad hoc appointments in government or public undertaking during the time the Code is in force. Ministers cannot enter any polling station or counting centre except in their capacity as a voter or a candidate.

MCC’s origin in Kerala

Kerala was the first state to adopt a code of conduct for elections. In 1960, ahead of the Assembly elections in the state, the administration prepared a draft code that covered important aspects of electioneering such as processions, political rallies, and speeches.

The experiment was successful, and the EC decided to emulate Kerala’s example and circulate the draft among all recognised parties and state governments for the Lok Sabha elections of 1962.

However, it was only in 1974, just before the mid-term general elections, that the EC released a formal MCC. It also set up bureaucratic bodies at the district level to oversee its implementation.

This Code was also circulated during parliamentary elections of 1977. Until this time, the MCC was meant to guide the conduct of political parties and candidates only.

However, on September 12, 1979, at a meeting of all political parties, the Commission was apprised of the misuse of official machinery by parties in power. The Commission was told that ruling parties monopolised public spaces, making it difficult for others to hold meetings. There were also examples of the party in power publishing advertisements at the cost of the public exchequer to influence voters. At this meeting, political parties urged the EC to change the Code.

So the EC, just before the 1979 Lok Sabha elections, released a revised Model Code with seven parts, with one part devoted to the party in power and what it could and could not do once elections were announced. The MCC has subsequently evolved as an integral part of conducting fair and free elections.

MCC’s evolution

The MCC has been revised on several occasions since then. The last time this happened was in 2014, when the Commission introduced Part VIII on manifestos, pursuant to the directions of the Supreme Court.

Part I deals with general precepts of good behaviour expected from candidates and political parties. Parts II and III focus on public meetings and processions. Parts IV and V describe how political parties and candidates should conduct themselves on the day of polling and at the polling booths.

Speaking at a conference on electoral reforms in Lucknow, in January 2011, then Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) SY Quraishi said that political parties must be credited with the development of the MCC. Quraishi said the MCC was “enforced not by law but by an agreement made to this effect by all political parties… [it] worked wonders as restrictions imposed under it are carried out by all governments and political systems without failure”.

Few days earlier, speaking at the valedictory function of the diamond jubilee celebrations of the ECI, the CEC had said the MCC was indispensable for ensuring “honest, free and fair elections”, and despite the fact that it had no statutory backing, it continued to be effective because it elicited the “moral sanction” of public opinion and had evolved virtually as a “moral code of conduct”.

Since 1991, the MCC has come to be seen as an integral part of elections, making the electoral contest democratic by ensuring that the party in power and those who staked claims to power would abide by it.

Criticism and challenges

In May 1990, the Goswami Committee on Electoral Reforms under the then law minister Dinesh Goswami made significant recommendations for reforms. Among these was the suggestion that the weakness of the MCC could be overcome by giving it statutory backing and making it enforceable through law.

The Goswami Committee suggested bringing certain areas within the ambit of electoral law and making their violation an electoral offence.

The government went on to propose an amendment to the Representation of People’s Act, 1951, to make the violation of some of the provisions of the MCC punishable. This Bill was, however, not passed.

Over the years, many have argued that the lack of legal enforcement would hinder the enforcement of the MCC.

However, it is also argued that the EC can enforce MCC through the powers it has. Clause 16(A) in the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, for example, gives the EC the power to suspend or withdraw recognition of a political party “for failing to observe the Model Code of Conduct or follow the lawful directions or instructions of the Commission”.

Court decisions

Election code is no bar for the government to execute court orders: HC

Ajay Sura, April 26, 2024: The Times of India