Encephalitis: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Deaths due to Encephalitis

2014

Encephalitis claims 1,495 lives in 2014

Dec 23 2014

The Centre admitted that efforts to control encephalitis had not been able to contain the high death toll even as BJP members in the Lok Sabha accused the state government of indifference.

In his calling attention motion in the Lok Sabha, BJP MP Yogi Adityanath pointed out that more children have died of encephalitis in a year than in the terrorist attack on the Peshawar school recently .About 1,495 people, mostly children, have died so far this year.

To increase efficacy of its drive against `brain fever', which has been rather severe in parts of eastern UP and Bihar, health minister J P Nadda said the Centre will also involve MPs, MLAs and local bodies. “Despite our policies and funding, results which should have come are not coming. We are alive to the sentiments expressed by members and committed to deal with the disease.“

Assam

2019

GUWAHATI: All districts in Assam, except Kokrajhar in western end of the state bordering West Bengal, are currently under the influence of Japanese Encephalitis (JE). The death toll due to JE has climbed to 49.

All the district deputy commissioners have been alerted and directed to step up the surveillance activities in coordination with the panchayat and urban local bodies along with strengthening of diagnostics and case management. “Assam is currently undergoing a transmission season for Japanese Encephalitis with 190 reported positive cases of JE and 49 reported JE deaths till July 5,” health minister Himanta Biswa Sarma said.

The state health department issued notification cancelling all types of leave for doctors, nurses and every personnel in the government health sector till September 30. “Only the deputy commissioner can allow leave in emergency cases,” Sarma said.

“We have also issued directives that no doctors, nurses and health personnel shall remain out of the place of posting. Anyone found absent from his or her place of posting will be dealt with seriously. His or her unauthorized absence will be considered as criminal dereliction of duty and an FIR will lodged against him and her,” Sarma said.

The health minister said that Assam is ecologically favourable region for the spread of Japanese Encephalitis due to heavy rainfall, large paddy fields with big water body, piggery farming or domestic pig rearing almost throughout the state, which support the virus propagation.

He said that vaccination for Japanese Encephalitis through the routine immunization for children is currently going on regularly and adult vaccination was done in 20 districts during 2016-17 where the coverage was about 68%.

“The situation in the state is under close watch and all preventive measures are being taken. Therefore to combat the situation, 12.8 lakhs blood slides have been collected by our fever surveillance network, 1094 effected villages have been covered through intensified fogging operations. Treatment and diagnostic cost at medical colleges and district hospitals are being borne by the state,” he said.

Bihar

How encephalitis stalked Bihar

June 22, 2019: The Times of India

From: June 22, 2019: The Times of India

From: June 22, 2019: The Times of India

From: June 22, 2019: The Times of India

See graphics:

AES cases, district-wise, January 3- June 19, 2019

AES deaths, district-wise, January 3- June 19, 2019

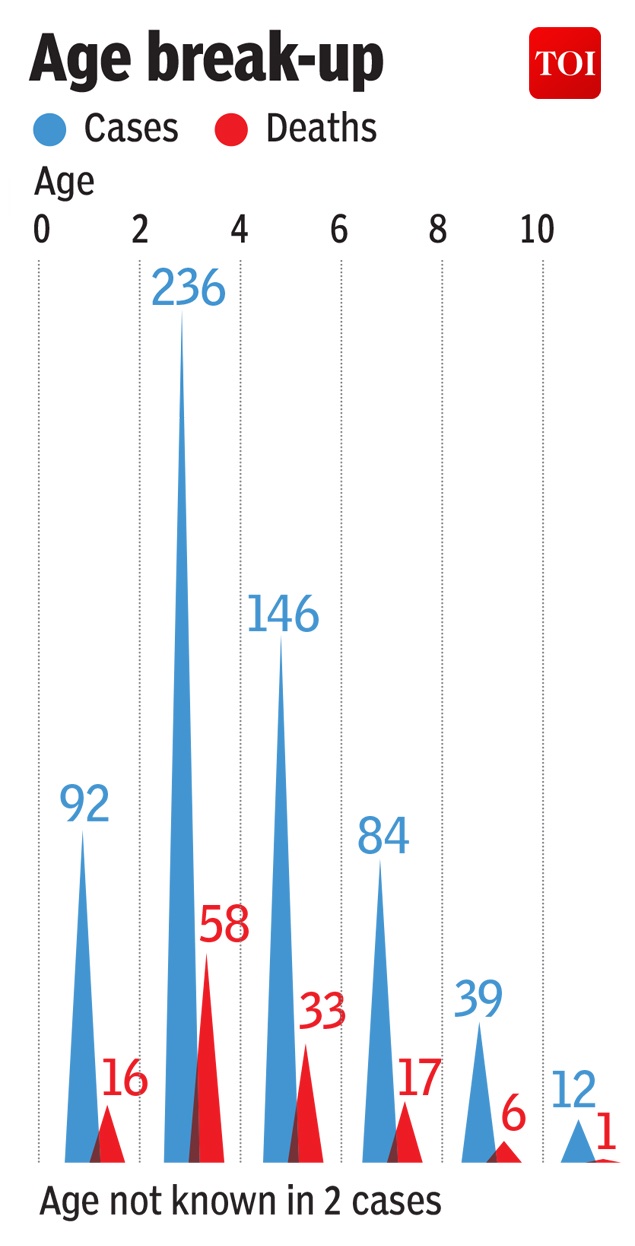

AES cases and deaths, age-wise

…and why

Neerja Chowdhury, July 2, 2019: The Times of India

The Acute Encephalitis Syndrome (AES) deaths in Bihar – of over 150 children last month – bear tragic testimony to the state’s tattered public health system. For there can be nothing more shameful for any government – or society – than the death of a child whose life could have been saved.

This is not the first time that AES has hit Bihar; it claimed 196 young lives in 2014. The government had formulated clear guidelines of dos and don’ts but obviously it became complacent, either because the number of deaths had abated in the last two years or because the entire government machinery was busy with Lok Sabha elections.

The deaths in 23 districts were all the more shocking because Nitish Kumar, in power for 14 years, is one of the few chief ministers who has shown sensitivity to socioeconomic issues. Soon after he took over in 2015 he had announced the seven “Nishchays” of his government, which included access to higher education, toilets, drinking water, jobs for youth, electricity for every house.

AES has struck the children of the poorer communities – the Dalits and Mahadalits, and those of the Extremely Backward Castes (EBCs) – the most. As irony would have it, it was Nitish Kumar who had fashioned his successful rainbow coalition around the empowerment of these very communities. There has hardly been any child hit by the disease who’s from the upper castes or middle classes.

In Musahri block of Muzaffarpur district – which accounted for 453 out of 725 cases this year and just under 100 deaths – Chunchun Devi, who lost her 4-year-old daughter Raveena, looked stoic. The only emotion she betrayed was to say, “I don’t even have a photo of her.” She has received a cheque from the government for Rs 4 lakh as compensation but needs a PAN number to deposit it. The cheque is made out to her husband, the bank account is in her name. And they do not know how to acquire a PAN card!

I decided to go to AES affected Musahri block because it was here that Jayaprakash Narayan had worked in the early seventies, dissatisfied as he was with Vinoba Bhave’s “Bhoodan” movement to end poverty. It was during the JP movement soon thereafter for “sampoorna kranti” that many of those who have ruled Bihar in the last quarter century, including Lalu Prasad and Nitish Kumar, cut their political teeth.

Four decades down the line the Musehars, who survive by killing rats, or the Ravidas community to which Chunchun Devi belongs, remain at the bottom of the socioeconomic heap.

Whatever be the trigger for AES (litchis, or mumps, or acute heat – research needs to be stepped up on this), it is malnourished children who become easy prey to the disease. Doctors in Muzaffarpur’s Shri Krishna Medical College and Hospital confirmed that “80%” of the children brought to them were malnourished.

This was not surprising since Chunchun Devi – thin, short, pale, looking no more than 20 herself, with a 7-month boy in her arms and two daughters, 8 and 6 standing by her side (apart from having lost 4-year-old Raveena) – was a reminder that nutrition was not just about the right kind of food, but also about grappling with early marriage, frequent pregnancies, anaemia and mother’s nutrition.

What did surprise was that Bihar still has no clear nutrition policy, when there is a proactive National Nutrition Mission in place, launched by the PM last year.

The state also reels from a paucity of doctors and nurses, and the perennial problem of their not wanting to work in rural areas. There are a large number of vacancies waiting to be filled up, with 3,679 regular and contractual doctors against a sanctioned strength of 9,563. Surely it should not be impossible to motivate graduating medicos to give two years working in rural areas as their “give back”? Then of course the primary health centres, 533 of them, await modernisation; the district labs upgradation to test for infectious diseases; and HR data to be digitised.

How about an 8th “Nishchay” by Nitish Kumar – to ensure healthcare and nutrition to every child? How about a nutrition mission in Bihar, directly under the chief minister’s supervision, which would give the issue primacy and make coordination between ministries easier? After all Bihar did manage to reduce neo-natal mortality, still-birth deaths, and increased routine immunisation.

Muzaffarpur

2009-19

From: Piyush Tripathi & Ajay Kumar Pandey, June 18, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

The death toll from Encephalitis in Muzaffarpur, 2009-19

Uttar Pradesh

2017> 18: a success story

Sushmi Dey, June 23, 2019: The Times of India

While Bihar struggles to contain acute encephalitis syndrome, the eastern part of neighbouring Uttar Pradesh, which has also been a problem area, has seen a significant improvement with an over 67% drop in deaths due to the disease in 14 most-affected districts.

Japanese encephalitis and acute encephalitis syndrome were major health challenges in eastern UP and poor health infrastructure proved to a serious handicap for the Yogi Adityanath government in 2017 when a spate of child deaths — not all related to the disease — rocked BRD medical college in August, 2017.

More than 500 children died that year in Gorakhpur and its neighbourhood with as many as 14 districts of the region in the grip of encephalitis. The state government launched Action Plan 2018 with a multi-pronged approach in collaboration with the WHO and Unicef to tackle the encephalitis menace.

In 2018, deaths due to AES dropped to 166 from 511 in 2017. The number of encephalitis cases reported in 14 districts of eastern UP also dropped from 2,247 in 2,017 to 1,047 cases last year. In 2019 so far, 20 deaths have been recorded from 82 cases, according to UP government data. “The government worked on a plan and the results are for everyone to see,” says K K Gupta, director general of medical education and training in UP government. He said several measures included intensive vaccination and sanitation campaigns, improvements in health infrastructure and health resources (addition in beds and creation of more positions of nurses and paramedics apart from doctors.

Public health experts working in the region say Uttar Pradesh laid a lot of emphasis on early diagnosis and providing immediate care. In 2017, the UP government started a campaign against the disease involving multiple stakeholders. As a result, the outbreak of disease itself has decreased considerably in the last two years.

‘Litchi did not cause childrens’ deaths

Sushmi Dey, ’No litchi link to kids’ deaths in Bihar’, February 4, 2020: The Times of India

Almost half of children who died due to acute encephalitis syndrome (AES) in Bihar’s Muzaffarpur in mid-2019 had no history of litchi consumption, whereas majority of the rest were less than two years’ old and therefore not quite able to eat the fruit, preliminary studies have concluded ruling out litchi toxins as the cause of those deaths.

In the wake of these findings, Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) has ordered further investigation to ascertain the cause of sudden rise in deaths due to AES in Bihar last year. The Council will launch a study in April-May with the onset of summers to probe the matter, an official said.

“So far, majority of the investigations — by Indian as well as international researchers — have ruled out litchi consumption as a cause of these deaths. Hence, further probe is required to ascertain the cause and capture it,” the official told TOI.

In June 2019, Bihar witnessed a sudden spike in AES-related deaths with over 125 fatalities and more than 550 cases recorded in the state. While the state government had blamed heat wave and litchi toxins as the cause of these sudden deaths, public health experts and researchers have pointed to malnutrition and poor health infrastructure in the state to contain the disease.

Following the huge number of deaths, the Centre had appointed teams including researchers from ICMR, National Centre for Disease Control, National Institute for Nutrition as well as from Atlanta’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to Muzaffarpur to pin down the cause of the deadly disease. Doctors, paediatricians and epidemiological experts from New Delhi’s AIIMS, Safdarjung Hospital and public health experts from WHO and UNICEF also conducted initial studies in Bihar to determine the cause.

Preliminary findings also indicated the cause is of “noninfective origin” — which means it is “not a virus, any bacteria, fungus or a living organism”. Health experts say it is difficult to believe litchi as the cause of deaths. “There is a particular component in the fruit which can contribute to reducing blood sugar level if too many are consumed on empty stomach but there has to be other factors,” said a public health expert working in Muzaffarpur.

Official data suggest the Bihar government had been indifferent towards improving child nutrition and healthcare in this district. In Muzaffarpur, nearly 48% children under the age of 5 are stunted, 17.5% are wasted (too thin for their height), while 42% are underweight — a glaring sign of chronic under-nutrition, according to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-4.

Socio-economic profile of the affected

Bihar, 2019

Rema Nagarajan, June 24, 2019: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, June 24, 2019: The Times of India

A social audit of families of children admitted with acute encephalitis syndrome (AES) conducted by the Bihar government reveals just how poor they are. More than three-fourths of those surveyed would fall below the poverty line (BPL). The audit data accessed by TOI is for 287 of the families of children with AES reported till now.

The average annual household income of the families surveyed was a little over Rs 53,500 or about Rs 4,465 per month. The Rangarajan Committee had defined the poverty line in rural Bihar in 2011-2012 as a per capita monthly income of Rs 971. For an average family of five persons, this works out to Rs 4,855 per month. Even adding a very modest 2% annual inflation for the eight years since then would take that figure to Rs 1,138 today or about Rs 5,700 for a family of five people.

Over 77% of the families surveyed earned less than this and a large number of them had 6-9 family members or more. There were families that reported an annual income of as little as Rs 10,000 and the most well-off among those covered by the audit had an annual income of under Rs 1.6 lakh. Approximately 82% (235) of the households surveyed earned a living by working as labourers.

AES OUTBREAK

Audit: In 3/4th of cases, elders unaware of AES, PHC treatment

About a third of the families had no ration card and about a sixth of those who did have one had not received any rations the previous month. In 200 of the 287 cases surveyed (about 70%), the families said their children had played outside in the sun before being taken ill with AES. And 61 of the children had eaten nothing the night before they fell sick.

Roughly two-thirds of the families, 191, live in kutcha houses. Yet, only 102 had benefitted from the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana. Though 87% had access to drinking water, almost 60% did not have a toilet. Though the government claims to have provided ambulance services, 84% of the families did not use the service for taking the children to the hospital and in almost all these cases, they were not aware of it.

About 64% of the households were from areas surrounding litchi orchards and a similar proportion said the child who fell ill had eaten litchi. Surprisingly, in threefourths of the cases, the elders were not aware of chamki bukhar or AES nor were they aware that treatment for it was available at the primary health centre (PHC).

Only a quarter of the cases were referred to the primary health centre for treatment. This is not surprising, as in most AES cases, the symptoms surface in the early hours when most primary health centres are closed apart from the fact that many of them are severely understaffed.