Europe- India: trade relations

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

History

William Dalrymple, Sep 14, 2023: The Indian Express

From: William Dalrymple, Sep 14, 2023: The Indian Express

From: William Dalrymple, Sep 14, 2023: The Indian Express

From: William Dalrymple, Sep 14, 2023: The Indian Express

From: William Dalrymple, Sep 14, 2023: The Indian Express

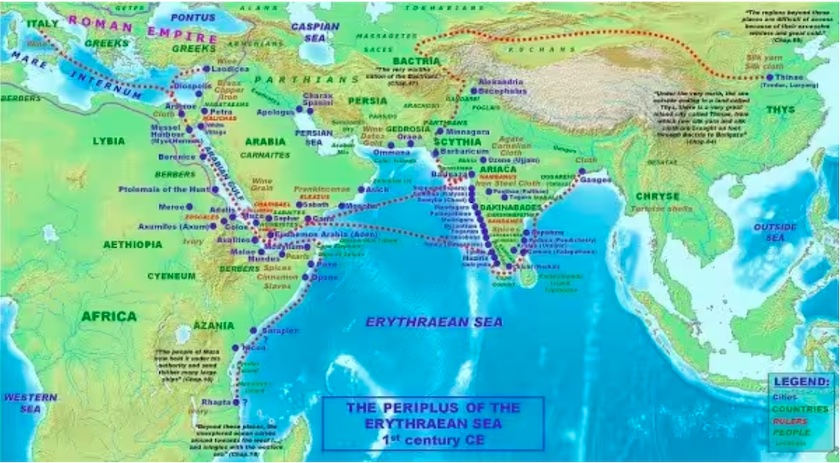

The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor announced at the G20 Summit harkens to an ancient trade route between the subcontinent and the Roman Empire. The existence of this trade, which peaked in the early centuries of the common era, has been known for long; however, evidence of its scale — eclipsing the more romanticised overland Silk Road— has only recently emerged strongly.

William Dalrymple’s upcoming book, The Golden Road, delves into this subject in detail. Here, he speaks to The Indian Express regarding the ancient Red Sea trade route, much bigger and historically more significant than the overland route from China.

What do we know about the ancient Red Sea trade route?

For years, we have known that there was trade between Rome and India in Antiquity. Sir Mortimer Wheeler was digging south of modern Pondicherry at Arikamedu in the 1930s and 40s, and established the existence of Indo-Roman trade in the 1st century CE. However, he incorrectly interpreted his finds solely in terms of Roman merchants trading to India: he failed to give Indian merchants and ship owners any agency in this trade, which they undoubtedly had.

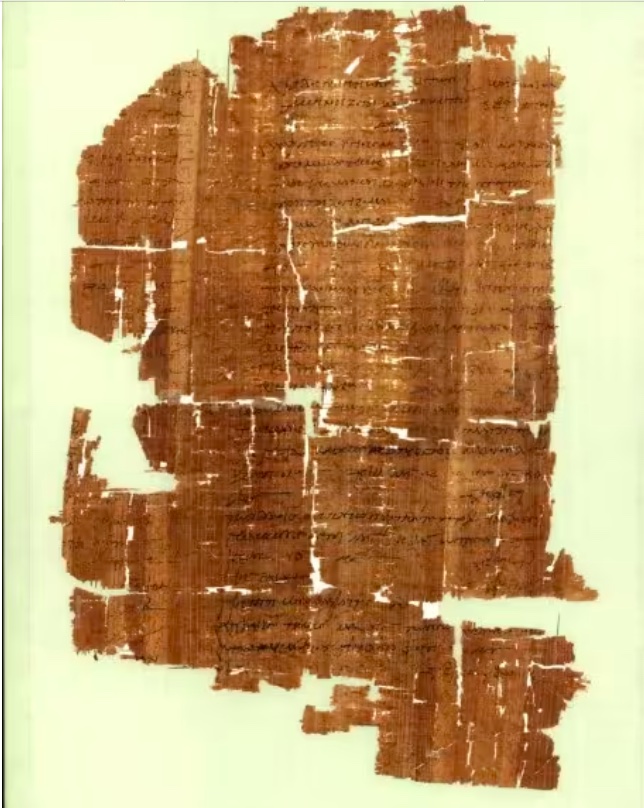

Also, no one, I think, realised the scale of this trade. According to latest estimates, custom taxes on the Red Sea trade with India, Persia, and Ethiopia may have generated as much as one-third of the income of the Roman exchequer. The principal source for this striking figure is the Muziris Papyrus — a document taken out by an Alexandria-based Egypto-Roman financier for the purchase of goods from an Indian merchant based in far-away Muziris on the coast of Kerala.

The Papyrus gives precise details of one particular cargo sent to the Egyptian port of Berenike from Muziris aboard the ship Hermapollon. The total value of the goods — calculated as worth 131 talents, “enough to purchase 2,400 acres of the best farmland in Egypt” or “a premium estate in central Italy” — is jaw-dropping. And a single trading ship such as the Hermapollon could apparently carry several such consignments, each worth a small fortune.

And how much would the Roman Empire earn from such a cargo?

According to the Muziris Papyrus, the import tax paid on the cargo of almost nine million sesterces was over two million sesterces. Working up from these figures, and the other receipts that have survived from the period, by the first century CE, Indian imports into Egypt were worth probably over a billion sesterces per annum, from which the tax authorities of the Roman Empire were creaming off no less than 270 million.

These vast revenues surpassed those of entire subject countries: Julius Caesar imposed tribute of 40 million sesterces after his conquests in Gaul while the vital Rhineland frontier was defended by eight legions at an annual cost of 88 million sesterces.

If the figures given on the Muziris Papyrus were correct — and there are no reasons to doubt them — then custom taxes raised on the trade coming through the Red Sea would alone have covered around one-third of the entire revenues that the Roman Empire required to administer its global conquests and maintain its vast legions, from lowland Scotland to the borders of Persia, and from the Sahara to the banks of the Rhine and Danube.

At the route’s peak, in the 1st and 2nd century CE, we had this maritime highway linking the Roman Empire and India, through the Red Sea, with many hundreds of ships going in both directions each year.

What was being traded on this route?

There was a great demand across the Roman Empire for luxuries from India: from the cinnamon-like plant called malabathrum, whose leaves were pressed to create perfume, to ivory, pearls, and precious gemstones. A famous ivory figure of a voluptuously pouting yakshi fertility spirit, found in the ruins of Pompeii, can be dated to this period. In fact, the city once had a shop which apparently sold nothing but ivory products. There was also demand for “exotic” goods, such as wild animals like elephants and tigers.

And of course, there were spices. India’s biggest export by far was pepper, large quantities of which have been found during excavations at Berenike, often in torpedo-shaped pottery jars, each weighing more than 10 kg. In fact, by the end of the first century, Indian pepper became almost as readily available as it is today. Around 80 per cent of the 478 recipes included in the Roman cookbook of Apicius included pepper. Nonetheless, it remained an expensive treat.

And what about the trade from Rome to India?

The flow of goods in the other direction was more limited. The Roman historian Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) says it was mainly gold that went to India, which was a problem for the Roman economy because the balance of trade was firmly in India’s favour. But we do have records of Indians having a taste for Roman wine.

Among the millions of fragments found at Oxyrhynchus, an Egyptian archaeological site on the Nile, was a locally rewritten version of Euripides’ play, Iphegenia Among the Taurians — but with the action transferred to India. Here the Indians speak a strange, meaningless mumbo-jumbo; as one scholar has noted, “the Indians are characterised by unintelligible speech, which presumably adds to the coarse humour.”

The Indians in the drama also show an insatiable appetite for Roman wine, and at one point, as the heroine makes her escape, the Indian characters all become drunk on the undiluted Mediterranean vintage. Charition’s (the protagonist) brother explains, “in places like this wine is not usually for sale, so when they get hold of it they drink it straight away”. (Modern visitors to dry Indian states such as Gujarat will recognise the scenario.)

There was also some trade in olive oil and Garum, an ancient Roman fermented fish paste, like the Tabasco or garam masala of the day, evidence of which has been found in Arikamedu and the sites in Kerala.

Was there trade on this route before the Common Era?

Yes, we have evidence of an Indian diaspora in the Middle East even at the time of Meluha (the Indus Valley Civilisation, c. 3300-1300 BCE). But it seems to have been more coastal and involved small quantities of goods.

In Roman times, this expanded to a vast trade with huge cargo ships moving directly between the subcontinent and the Roman Empire. The Romans basically ‘industrialised’ the trade, partly because they were rich enough to buy the luxuries that India had to offer.

The trade particularly picked up in the 1st and 2nd centuries after the Romans conquered Egypt, opening up for Roman merchants, who were adventurous enough to try to sail it, the route to India.

How organised was the trade, and how long did a typical journey take?

The evidence points to the trade being highly organised. Contracts were written between merchants in Kerala and shippers in Alexandria. Goods were shipped in containers just like today — so you would book a container and fill it with, say, ivory. There are even references to insurance. It was a highly sophisticated trade network.

Indians were quick to grasp that the heating of the Tibetan Plateau meant that the monsoon winds blow in one direction in winter and the other in summer. So if you got it right, you could sail with the winds behind you to Egypt in about six to eight weeks, and back again in about the same time. But you had to wait for a few months for the winds to turn.

This is perhaps a reason why we have evidence of the Indian diaspora renting houses in the ports of Egypt and staying in the country for some time. And we have literary evidence of Indian noblemen turning up at the games in Alexandria.

What roles did Indians have in this trade?

We know that Indians and many Indian dynasties were very much interested in seafaring. We have pictures in Ajanta of large double-masted ships. Also, ships were a common insignia in many early Indian coins. The coins of the Satavahanas, for instance, have images of ships on them.

We also have a lot of evidence of Indian sailors being very prominently involved in the trade. Graffiti left by Indian sailors (mostly Gujaratis from Barigaza, modern-day Bharuch) from this period has been recently found in the Hoq caves on the island of Socotra, a popular stopover at the mouth of the Gulf of Aden.

Of the 219 inscriptions here, dating from the second to the fifth century CE, 192 are in the Indian Brahmi script, and one each in Bactrian and Kharosthi. They give names that are unquestionably Indian: “Vishnu, son of the merchant Ganja”, “Skandabhuti, the Sea Captain”, or the nicely laconic, “Bhadra arrived”.

There are also images of Buddhist stupas, Shaivite tridents, swastikas, Syrian Christian crosses, and pictures of large three-masted Indian ships, as well as prayers to Krishna and Radha, and invocations to the Buddha.

What is lesser known, however, is to what extent the shipping was owned by Indians. The surviving papyri indicate that much of the shipping coming out of the Egyptian Red Sea ports seems to have been owned by Alexandrian businessmen — but given that so many of the sailors working the route were Indian, Indian ownership is not out of the question.

How does this route compare with the Silk Road?

The centrality of the Indian subcontinent as the ancient economic and cultural hub of Asia, and its ports as the place of maritime East-West exchange, has been obscured by the seductively Sino-centric concept of the ‘Silk Road’. In fact, despite its modern popularity, the idea of a Silk Road — an overland trade route supposedly stretching all the way across Asia from Xian in China to Antioch in Turkey — was completely unknown in ancient or mediaeval times: not a single ancient record, either Chinese or Western, refers to its existence. In fact, even Marco Polo, the man now most closely associated with the Silk Road, never once mentions it.

The term was first coined in 1877 by the Prussian geographer Baron von Richthofen who was charged with dreaming up a route for a railway linking Berlin with Peking. It was not used in English at all till about the 1930s. It became popular only in the 1980s-90s, partly because it has such a romantic feel about it — connecting the East and the West. Every second hotel or beer bar, from Beijing to Istanbul, started calling itself the ‘Silk Road Hotel’ or some such. I think one should realise how often our ideas are products of the moment, rather than balanced conceptions of history.

Today, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative has politicised this — actively mobilised the idea as part of Chinese foreign policy, elevating it to unquestioned fact and thus, making China the end of a worldwide trade network.

This is not to say that the Silk Road did not exist at all. It certainly existed during the Mongol period (13th and 14th centuries CE) when the whole area between China and the Mediterranean was under one Mongol Empire. But if you’re looking at the Roman period, there’s no evidence that China and Europe knew of each other’s existence beyond the realm of legend. The focus on the Silk Road is completely wrong for this period. In fact, Chinese silk seems to have reached Rome during this period via the ports of India. For instance, overland through Kushana territory in northern India, to the ports of Gujarat and the mouth of the Indus.

Why is the scale of Indo-Roman trade emerging only now? Is it just the discovery of new evidence, or something more?

Definitely, a lot of new evidence is emerging, for instance in digs like Muziris in Kerala and Berenike in Egypt. For instance, just last March, the head and torso of a magnificent Buddha, the first ever found to the west of Afghanistan, was discovered at the site in Berenike along with a triad of early Vaishnav deities. While there was no inscription, the director of the dig, Steve Sidebotham, believes it was probably commissioned by a wealthy Indian Buddhist sea captain in thanks for his safe arrival in the Roman Empire. A lot of new material is definitely emerging.

But India has also underplayed its importance as a centre of ideas and trade in the early classical period. Often, Indian nationalists swell with pride at the achievements of ancient India, but they usually talk about the distant Vedic past. To me, the most interesting period is the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, when India was exporting its ideas all over the world — from sending Buddhism to China to providing luxuries to the Roman world.

While many great Indian scholars have researched this subject, particularly the great Himanshu Prabha Ray, I think they have not always been perhaps as interested in making their work accessible to a wider audience, so their findings are not as widely known as they should be.

Now that we are learning about India’s centrality in this trade, what is next?

There are many questions still left to be answered. For instance, we know that Buddhist monasticism was extremely prevalent all over India at the time. It even began to spread to Central Asia and western China. Did this, in any way, influence the form of Christian monasticism that began during the late Roman period? We don’t know yet. But it is a question that we now begin to ask.

Many more such questions may be asked because now we know that India and Rome were not two distant worlds, cut off from each, but rather two worlds directly in contact on an annual basis.

William Dalrymple is a scholar-historian based in New Delhi and a Visiting Fellow at All Souls College, Oxford. His most recent work is the Company Quartet, a collection of four books published over nearly two decades that chronicle the late Mughal Period and the rise of the East India Company. His upcoming book ‘The Golden Road’ will be released in 2024 by Bloomsbury. It deals with the spread of Indian ideas and influences across the world, from the Red Sea trade route discussed in this piece to the spread of Indian mathematical systems in Europe.

See also

Europe- India: trade relations

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and India