Faiz Ahmad Faiz

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Faiz

Faiz In Love

By Anjum Niaz

Was Faiz perpetually in love? Our elders never explained his emotional heft. They merely recited his verses and heard Noor Jehan and others sing his masterpieces.

Breathes there a man with soul so dull/ Who never to himself hath said/ I have also been in love!/ Whose heart hath ne’er within him burn’d/As time his footsteps hath turn’d/ From wandering on a romantic strand.

My apologies to Walter Scott, the English poet, for tampering with his fine verses. He wrote on patriotism. I’ve changed them to love, a universal alchemy afflicting us all from moment to moment. Even the father of psychoanalysis and the unconscious mind, Sigmund Freud, said, “One is very crazy when in love.”

Was Faiz perpetually in love? Our elders never explained his emotional heft. They merely recited his verses and heard Noor Jehan and others sing his masterpieces. We too were pulled in. Surely you must remember the number of times you heard Mujh se pehli se mohabbat mere mehboob na maang. I do. The song was filmed on Shamim Ara in the movie Qaidi. She sang it for Darpan, the hero. Lost in the ‘filmi’ world of romance and the loveliness of our film stars, little did one care as to who had written those immortal lines or for whom.

Young, dreamy and always breathlessly in love. That’s how syrupy the passage of youth is. We were young once. And in love. Not just with one but many who crossed our path. Life was made up of sweet conquests, secret rendezvous, love letters and innocent extravaganza. We wanted time to stand still and listen forever to Noor Jehan and Farida Khanum sing love songs that stirred sentiments too deep for tears. In our living room I would forever play the 78 RPM black plastic record on our radiogram and let the spirit soar like an eagle, free and fearless.

Each summer when the mist descended and mingled among us, when the rain drops fell spritzing our faces with heaven-sent freshness, we wound our way to the Murree Club on the hill. There stood an auditorium with a stage that must have seen Pakistan’s most talented perform in the festival called Jashn-i-Murree. It was a yearly ritual, pregnant with a promise of being the best show in town. And it never once did disappoint us. Summer residents fleeing the heat of the plains, from Pindi Point to Kashmir Point, filled the auditorium. The year 1969 was unique. We had Faiz Ahmad Faiz among us. I went to the mushaira because of my parents. We got home in the early hours. It was still raining and romance generated by Faiz’s poetry was still circling in the air.

The remains of that day came alive when I sat next to Abu Shamim Ariff at the launch of Agha Nasir’s book on Faiz, called Hum jeete ji musroof rahe. Shamim reminded me that he was the SDM (Sub-Divisional Magistrate), Murree, and it was he who had invited Faiz to come and recite his poetry. “Underneath his obvious calm there lay a whole world of emotions, feelings and experiences,” he recalled. With Habib Jalib, Ahmad Faraz, Hemayat Ali Shair and Qateel Shifai gunning for the khakis (seated in the front row), Faiz worried for the young SDM getting into a soup with the army. “Shamim Mian apki naukri toe gaee!”

Agha Nasir’s book event was at the Pakistan Academy of Letters whose guardian is the polite Iftifkhar Arif (one hears the PPP wants its own man there now, and hopes it’s not some philistine). The book is a revelation. A juxtaposition of Faiz’s poetry and humanism. It casts the great poet in the centre and names the dramatis personae that came into his life and then exited the stage. The raconteur does not call his book a book of research or a critique. Instead, he calls it a labour of love, a “debt that he owed” to their friendship. Indeed, Agha Nasir has paid his ultimate tribute to his friendship in telling the world why, where, when, which, what, and how Faiz’s 100 best poems got written.

The author has framed his narration with a dignified charm. Agha Nasir scanned Faiz’s letters, correspondence and family papers. He went to his daughters Salima and Moneeza in Lahore to corroborate anecdotes he had collected from various sources. He dug deep to unearth gems that lay hidden and would have never come to light had he himself not excavated. Once the facts were in place, checked and rechecked, the book was born. And it was launched.

Yusuf Jamal was the chief speaker. “Who is this old man trying to imitate you?” asked Yusuf’s bride on their wedding day. But first, who is this Yusuf Jamal? Iftikhar Arif introduced him to us. He is a Faiz clone. He even recites Faiz’s verses in the same tone, tenor and verve.

But his bride, a St Joseph’s English-medium graduate, thought it was Faiz who was “imitating” her bridegroom while reciting poetry on their wedding night which according to Yusuf Jamal “stretched into the late hours.” His bride was rightly piqued for being upstaged by that “old man” on the most important occasion of her life!

Faiz’s poetry was inspired by the women he loved. Mujh se pehli se mohabbat mere mahboob na maang is one of them. It was written in honour of Dr Rasheed Jehan whom he had met while a lecturer at the MAO college in Amritsar. She gave him the Communist Party manifesto, gently nudging him to rise above himself and his amour to look at the larger picture around him depicting deprivation, exploitation and poverty. This became the turning point for the young Faiz. His poetry and his thinking changed forever.

Masood Mufti, another civil servant like Yusuf Jamal, is well known in the world of Urdu literature. He was a POW during the 1971 war. He like Faiz is a humanist who feels the pain of fellow humans. But he also wants change. He wants ordinary Pakistanis to be in charge of their destinies and not corrupt leaders who promise change but are dictators, even in civilian clothing.

He shared his innermost fears and hopes with us, as did Kishwar Naheed, the ever young-at-heart feminist. She spoke of the days when she’d visit Faiz in jail at Lahore. He lived in sub-human conditions. He’d always be smiling; never complaining.

Munnoo Bhai was the chief guest. He lifted our hearts with his characteristic humour artfully nuanced with his remembrance of Faiz.

Faiz Ahmad Faiz II

Inner dimension of Faiz’s poetry

Told with ease and elegance, Agha Nasir’s Hum Jeetay Ji Masroof Rahay is a kind of biodata of Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s one hundred poems, like they were living beings with a soul, offspring of the poet’s passing liaisons and abiding relationships with life. It is a ground-breaking work, a record of those inspiring moments, touching events, shocking happenings, tragic situations, unexpected encounters and dalliances of the heart that moved the great poet to give us some of his most memorable poems. And for once, mercifully, it is not the run of the mill critique of his art but the drama of the poet’s interaction with the world of his time and its transformation in his hands into throbbing testimonies of unalterable history.

Agha Nasir intended to write this book when Faiz Sahib was alive and had actually discussed his plan with him. He had liked and approved the idea. But before the work could be taken in hand Faiz Sahib died. Yet Agha Nasir did not abandon the plan and decided to collect necessary information from his friends and family, the poet’s own writings and the published material of other writers. It was a difficult enterprise to begin, and as it often happens, one takes one’s time and is pushed to such undertakings only in desperation when it seems if one didn’t do it now, it would never be done. Agha Nasir had this feeling when one by one the friends and contemporaries of the poet started to depart from the scene. But once begun the work became a labour of love.

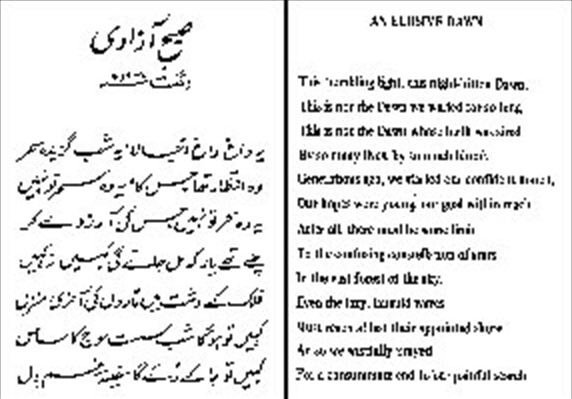

Agha Nasir introduces his book as a different kind of work since it is neither a critical review of Faiz Sahib’s poetry, nor a commentary on his political and national attitudes and philosophy of life or either his biographical or personal sketch, though where needed, all these elements do get a brief mention. The one hundred poems which he has selected to annotate them with their historical, situational or emotional background have been grouped under 17 headings according to events in the country’s and the ebbs and tides in the poet’s life. Yeh dagh dagh ujala comes under ‘national events’, shishon ka masiha koi nahin under ‘political circumstances’, Hum ke thehre ajnabi under ‘fall of Dhaka’, Dashte tanhaee mein under ‘moments of loneliness’ and so on and so forth.

The poignant occasion when Faiz Sahib recited Yeh dagh dagh ujala has been described in the words of Dr Aftab Ahmad: “The partition of the Subcontinent was announced on 3rd June. After a few days the summer vacations began. I went to Kashmir with my family. In the beginning of August we came to Srinagar and took residence in a house boat. Across the river in a bungalow the families of M.D. Taseer and Faiz Sahib were putting up. Two or three days after the 14th of August Faiz Sahib also arrived. I met him the next day at Taseer Sahib’s place. Bashir Hashmi and Dr Nazir Ahmad were also there. Faiz Sahib, with some hesitation which would heighten in the presence of elders, told us that a poem he had begun in Lahore was completed while on way to Srinagar. On Taseer Sahib’s asking he read this poem for the first time.”

Agha Nasir also describes how this greatest of Faiz’s poem was criticized both by the progressives, critics of the Left and the poets and writers of the Right wing. How could the dawn of freedom be described as a ‘sullied or tarnished morning’ they barked ignoring, what Prof Fateh Muhammad Malik said, Faiz Sahib’s deep love for his country reflected in the poem.

On the fifth anniversary of independence Faiz Sahib was incarcerated in Hyderabad jail. Describing the festive arrangements in the prison he wrote to Ellis it felt as if they were not in jail but in Anarkali Bazaar. “Next morning I woke up with a strange feeling of joy and I immediately sat down to write, which I am sending you with this letter. I was much surprised that it took no time to write and by breakfast time I had nearly completed it. I am still drunk with it and have some apprehension that I might some day become a poet.”

This was the occasion of that great and popular poem Nisar mein teri galyon pe ay watan ke jahan. After the death of the Quaid-i-Azam and Liaquat Ali Khan’s martyrdom all sincere and patriotic leaders had dispersed and the country had become a centre of intrigues, writes Agha Nasir. Malik Ghulam Mohammad had become the governor general through palatial conspiracies and Khwaja Nazimuddin was too weak a prime minister to stop the decline. Seeing it all from behind the walls of the Hyderabad jail Faiz captured the national rot in the lines of this poem.

During the days behind the bars Faiz Sahib also composed some poems and ghazals to give heart to his jail mates who later admitted that what gave them the courage to go through confinement were those verses of his, in particular the famous tarana: aye khak nashinon uth baitho who waqt qareeb aa pohncha hai/ jab takht giraey jaen ge, jab taj uchhale jaen ge. Ellis also wrote about it and said it was the poet’s most favourite composition in qawwali form.

Aaj bazaar mein pa ba jolan chalo was written in 1959 when he was sent handcuffed in a tonga from the Lahore central jail to see his dentist. A procession of admirers followed the poet who was moved by the people’s love. Mujh se pehli si muhabbat meray mehboob na maang marks his break with the romantic past in Lahore and his induction into Left politics on the prodding of Dr Rashid Jahan in Amritsar. The poem also refers to his infatuation with a Kashmiri beauty and disappointment in love. He confessed that to Amrita Pritum and Zehra Nigah.

I.A. Rahman, in his thought-provoking preface to the book, describes the integration of verse to history as an enviable feat as it very concisely recounts the bedevilled story of Pakistan also, that Faiz Sahib had, in a humourous vein, predicted to continue without suffering any change. As to apprehensions that bridging the ‘disconnect’ between event and verse would somehow limit the impersonal expanse of Faiz’s poetry by particularising it, is a somewhat fancy thought to me. Dante’s unrequited love for Beatrice gives the Divine Comedy its soaring altitude. Agha Nasir has traced an inner dimension of Faiz’s work, shown the man the poet was; what he felt and thought.

Faiz III

Breaking Fresh Ground

Reviewed By Humair Ishtiaq

HONESTLY, we are too close to the times in which Faiz Ahmed Faiz plied his trade to even try to sit in judgment over settling his place in Urdu literature’s hall of fame alongside the classical elegance of the likes of Meer, Ghalib, Iqbal and the rest. That he will have a place is not under debate though.

To ascertain someone’s literary status is, in any case, a tricky undertaking. More so, when the man in question and the jury happen to belong to the same era. This perhaps explains the passion of literary circles to continue debating how and where the future historian will treat and place Faiz in comparison with, say, Josh Malihabadi.

The literati used to be divided over who among the two modern-day greats was the greater. However, with time, Josh seems to be losing the debate, giving credence to Mushfiq Khwaja’s assertion that while Josh was the greatest poet of his time, ‘the same cannot be said of his poetry!’ Regardless of what the verdict might be on Josh — or, for that matter, on Noon Meem Rashid and Meeraji — Faiz remains a class act who seems to be gaining strength with the passage of time. And, indeed, there are reasons for it.

He had the capacity to universalise his creative output by taking up fresh subjects while keeping in touch with the classical idiom of Urdu poetry. This made him popular among even those who were diametrically opposed to his political and social beliefs. Even when Faiz spoke of his ideals, he used the traditional idiom of ‘mehboob’ to bring home his point without putting anyone off.

This is something that cannot be said of his contemporaries. Those who followed him tried their hand to varying degrees of success, but it is something that takes nothing less than a Faiz to do it. And therein lies his greatness.

The literature being generated about him today will form the basis of future research which will give way to a dispassionate, unbiased verdict in the long run. The quality and probity of today’s work, as such, holds the key to a future assessment. The critic of tomorrow will, indeed, be indebted to Agha Nasir for his recent work on Faiz, Hum Jeetay Ji Masroof Rahey.

It is one of the best works on the poet and goes a step beyond the highly readable account penned by the late Dr Aftab Ahmad titled, Faiz Ahmad Faiz: Shair Aur Shakhsiat (Maktaba-i-Daniyal, Karachi.) The path Agha Nasir has chosen is, indeed, groundbreaking. He has taken the reader beyond the man and his poetry by providing him a glimpse into the circumstantial reality of the times and the thought process that together led to the birth of literary gems.

Take, for instance, the famous poem titled Hum Jo Tareek Rahoon Mein Marey Ga’aay. While it has used captivating imagery to spellbind the reader, the poem was actually conceived by Faiz during his detention at Montgomery Jail in 1954 as his response to the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenburg, an American couple that was given the death sentence for having spied for the Soviet Union.

Faiz had the capacity to universalise his creative output by taking up fresh subjects while keeping in touch with the classical idiom of Urdu poetry. This made him popular among even those who were diametrically opposed to his political and social beliefs.

While the poet is praised the couple for having sacrifised their lives at the altar of their beliefs, the imagery, idiom and diction of the poem is such that the reader need not know the context to be able to enjoy it. Indeed, not many would have known the context anyway. By providing the context, however, Agha Nasir has added to Faiz’s stature as a poet by attesting his skill of using momentary inspiration to generate timeless poetry.

That Agha Nasir had the good fortune of having a close association with Faiz is quite evident in the text, but it has a very positive ambience about it which does not tax the sensibilities of a cultured reader because Agha had the good sense to keep the focus on the subject. It is not always easy to avoid the temptation of basking a little in reflected glory, but Agha has done just that and for that alone he deserves a round of commendation.

Besides, when personal feelings are intense and emotional, it becomes a challenging task not to lose one’s objectivity. It again goes to the credit of the writer that he has been able to walk the forbidding path, which must have been riddled with frightening potholes, with grace and integrity.

There is just one thing in the book, however, that may bug the reader a bit. Though elaborately categorised in 17 distinct segments, and with fresh backdrop specific to each piece of poetry that Agha Nasir has picked, the text tends to become repetitive while trying to capture the whole political, social and family background time after time after time. A little more time on the editing table would certainly have taken care of the issue. Having said that, it is nothing more than a minor flaw in an otherwise captivating work for which the writer deserves due accolade.

Faiz the person, as is common knowledge, was an easygoing character, almost bordering on lethargic. But Faiz, the poet, was just his opposite: revolutionary, optimistic and, indeed, a staunch romantic. Even when he lamented the adversity of ‘today’, the light at the end of the tunnel always remained well within his sight. The book comes as a confirmation of this. The historian of tomorrow will be as grateful to the writer as is the reader of today.

Hum Jeetay Ji Masroof Rahey

By Agha Nasir

Sang-e-Meel Publications, Lahore.

ISBN 10-969-35-2153-6

Pp349. Rs750