False news/ fake news

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

YEAR-WISE DEVELOPMENTS

2017 – 21

August 6, 2023: The Times of India

From: August 6, 2023: The Times of India

A 2018 survey by Reuters Institute and the University of Oxford found that the fear of fake news cuts across age groups. A majority of Indians who access news online said they are “worried whether online news they come across is real or fake”. Two out of three respondents, representing the English-speaking population in India, said smartphones were their main device for accessing online news while close to a third said they only use mobile devices for tracking news online. The kind of disinformation users find concerning spans hy per-partisan content (51%), poor journalism (51%) and false news (50%).

Rising Crime Graph

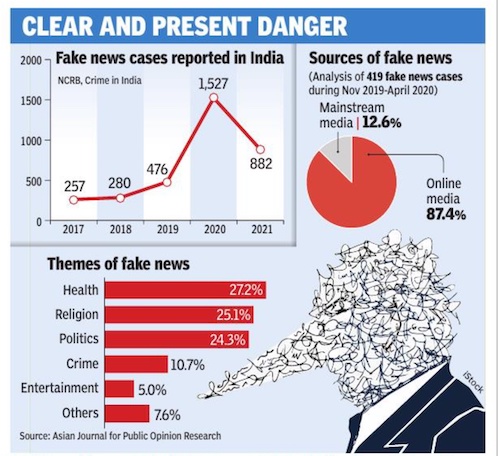

In 2017, the earliest year for which data is available, there were overall 257 reported cases of the circulation of fake news/ rumours in India, per the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data. By 2020, that figure had jumped to 1,527 cases, a nearly 500% rise. The number came down in 2021, the latest reported data, but at 882, was more than three times that in 2017. Research shows that fake news, perhaps due to its typically sensationalised content, manages to spread faster and much wider than actual reports and facts. An analysis of 12 years’ Twitter data starting 2006 showed that “whereas the truth rarely reached more than 1,000 Twitter users, the most pernicious false news stories... routinely reached well over 10,000 people”.

It Thrives Online

A 2021 study published in the Asian Journal for Public Opinion Research (AJPOR) that scanned 419 instances of social media fake news found that online media, not traditional sources like print and broadcast news, accounted for the vast majority of misinformation. Health, religion and politics were the most common subjects of fake news.

Another 2021 study, also in AJPOR, found that Facebook and Twitter were the main platforms for spreading fake news. Of the 90 cases of fake news analysed, 81% were shared on Facebook and 49% on Twitter. Half of these fake reports were in video format, and about a third were images with text. The spread of fake news was especially rapid during the Covid-19 pandemic. A study by University of Michigan researchers shows that fake stories promoting unverified cures and treatments rose sharply within months of the first cases being reported in China. The report said that while many Covid-related fake stories were newly fabricated, for other subjects like crime and culture, perpetrators were “repurposing” older news stories.

A survey conducted by Microsoft in 2019 found that more than 60% of Indian respondents had seen fake news online, compared with 57% of the global population. More than half of those surveyed also said they had been exposed to online hoaxes and more than 40% said they had faced phishing attempts.

Mob Lynchings To Health Hazards: What Fake News Can Trigger

In 2017, after rumours of child kidnappers and organ theft spread on WhatsApp, seven men were lynched in Jharkhand. In 2018, a mob killed one man and injured two others in Karnataka over kidnapping rumours. In Assam, two tourists were killed on unfounded suspicions of child abduction in 2018. In most of these lynchings, no actual kidnappings had been reported in the previous three months in the area concerned. Misinformation about kidnappings and cow slaughter led to at least 24 deaths in 2018. In 2020, a mob in Maharashtra killed three men wrongly suspected of theft following WhatsApp rumours.

In just the first three months of the pandemic, 800 people died because of Covidrelated misinformation and 5,800 were hospitalised across the world, reports say. In many cases, this was a result of drinking methanol or alcohol-based cleaning products in the belief that it would cure Covid. During the pandemic-induced lockdowns, people were not only consuming more online news but also coming across more fake news than before, even though fake news detection improved during Covid. Many fake news stories talked up unverified treatments and therapies, including bleach, hydroxychloroquine and even cow urine. Further, like in the Tablighi Jamaat case in March 2020 in Delhi – where a congregation in Nizamuddin was falsely labelled a superspreader event – fake news also took on a communal dimension.