Feroze Gandhi

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The man and his politics

His politics

Sagarika Ghose, February 25, 2023: The Times of India

Long before Rahul Gandhi, there was Feroze Gandhi. In a recent debate in Parliament, BJP attacked Congress on Jawaharlal Nehru, saying if Nehru was indeed such a great leader why did the current Gandhi family not bear his name, and why did they instead choose to call themselves ‘Gandhi’. The answer is of course simple: Rahul and Priyanka, as is the near-universal norm, bear the surname of their paternal grandfather Feroze Gandhi, husband of Indira, their grandmother.

Ironically, Feroze himself had no political pedigree. He wasn’t a dynast. He was an entirely self-made yet stellar parliamentarian. His family may today be accused of nepotism and dynasticism, cast as Lutyensland “naamdaars”, in the seeming culture war of “naamdaar” vs “kaamdaar”.

But Feroze himself was an Allahabadi “kaamdaar”. A Parsi who spoke fluent Hindustani as well as several Allahabadi dialects, his constituency Raebareli elected him with record margins in the elections of 1952 and 1957. Indira didn’t inherit Raebareli from her father (whose constituency was Phulpur), but from her husband. Mahatma Gandhi said of Feroze: “If I could get 7 boys like Feroze to work for me, I will get Swaraj in 7 days. ”

Feroze was born in 1912 in Bombay to marine engineer Jehangir Faredoon Gandhi and his wife Rattimai, a Parsi family with deep roots in south Gujarat. There is no documentation to show that Feroze was born Muslim as some have suggested. Some have also said Feroze’s name was spelt Gandhy in a birth certificate. Gandhy is simply an anglicised Parsi community spelling of Gandhi and the two were used interchangeably in British India. Feroze himself wrote his name as Gandhi, even though some members of his family, for example his sister Tehmina, used the surname Gandhy.

Newspaper items in the 1930s about FerozeWhen the Nehru government dismissed the EMS Namboodiripad government in Kerala, Feroze went on the warpath with both his wife (Indira was then Congress president) and father-in-law use the name ‘Gandhi’.

To imply that the present day Gandhis have adopted Feroze’s surname to claim a link to Mahatma Gandhi is to ignore the fact that Gandhi is a fairly common surname in Gujarat and there are many Gujarati families named ‘Gandhi’ who have no links or family claims on the Mahatma. Feroze’s own political career was short-lived but outstanding. Not only did he never have any help from his father-in-law, the two had a difficult, often adversarial relationship.

Family members remarked on Feroze’s often discourteous and aloof behaviour with Nehru, whom he also greatly admired.

Feroze was drawn to the independence movement because of his deep attachment for Kamala Nehru and Nehru. However, when it came to Feroze marrying Indira, Nehru was so implacably opposed to the match that Mahatma had to intervene. However, once they were married, Nehru did try to help Feroze’s career by making him director of the National Herald. Feroze made a mess of the job until he found his metier as a parliamentarian. In the Lok Sabha, Feroze took his father-in-law’s government to task on many issues. ‘Red’ (a reference to Feroze’s fair complexion), round and Pickwickian, Feroze enlivened Central Hall with his sense of humour, his designated corner named Feroze’s Corner, veteran journalist Inder Malhotra recalled.

Feroze shot into the limelight when through a careful investigation he exposed how the LIC bailed out Haridas Mundhra, a big donor to Congress, through a loan. The “Mundhra Scandal” rocked Parliament and Nehru’s close associate and finance minister TT Krishnamachari had to resign. Nehru was forced to set up an inquiry commission because of his son-in-law’s exposé.

Feroze kept up his attacks on Nehru’s government throughout his tenure as MP. He introduced the Proceedings of Legislature (Protection of Publication) Bill, 1956 giving journalists the freedom to report parliamentary proceedings.

In 1959, when the Nehru government dismissed the EMS Namboodiripad-led communist government in Kerala, Feroze went on the warpath with both his wife (Indira was then Congress president) and father-in-law. He called Indira a fascist and a bully and had violent arguments with her. “Feroze seems to resent my very existence,” Indira wrote to her friend Dorothy Norman at this time.

Unlike today’s family-trumpeting politicians, Feroze had nothing to do with the VIP cult around his wife and father-in-law. He proved his worth by performing remarkably well as a parliamentarian.

Feroze died when he was 48, in 1960. Struck by the huge crowds that turned up at his funeral, Nehru remarked: “I didn’t know Feroze was so popular. ” So, Feroze Gandhi wasn’t a nobody with just a famous surname. He was a gifted multi-faceted man. BJP needs to find better ways to corner Nehru-Gandhis than pointing to Feroze, who remains a symbol of uniquely democratic behaviour. He was a son-in-law unafraid to challenge his own powerful father-in-law repeatedly and publicly on points of constitutional principle, Feroze was a man who scorned the “family raj”.

A backgrounder

Yashee, February 18, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Yashee, February 18, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Yashee, February 18, 2023: The Indian Express

Feroze Gandhi was a freedom fighter, MP, and husband of Indira Gandhi. He was the one who exposed the Mundhra scandal in Parliament, and was perhaps among the first people to call his wife a ‘fascist'.

The ‘Gandhi’ in Rahul Gandhi’s name comes from Feroze Gandhi, his paternal grandfather, freedom fighter, journalist, and Member of Parliament from Raebareli. He passed away in 1960, a few days before he would have turned 48.

From Feroze Ghandy to Gandhi

Feroze Gandhi was born Feroze Jehangir Ghandy on September 12, 1912 in Bombay. His parents, Ratimai (née Commissariat) and Jehangir Faredoon Ghandy, were Parsis, and Jehangir worked as a marine engineer.

A young Feroze moved to Allahabad after his father passed away, to live with his aunt Shirin Commissariat, a surgeon at the Lady Dufferin Hospital. Feroze was a student at the Ewing Christian College when, at the age of 18, he had his brush with the two forces that would change his life forever – the freedom struggle, and the Nehru family.

Jawaharlal Nehru’s wife Kamala Nehru, who would later become Feroze’s mother-in-law, was among the satyagrahis picketing outside Ewing Christian College. Kamala fainted in the heat and crowds, and Feroze jumped to her aid. From then on, Feroze dropped out of the British-staffed college and threw himself into the freedom struggle, spending a lot of time at Anand Bhawan, the Nehru family home and important political centre. It was also around this time that he changed his surname from Ghandy to Gandhi, in honour of Mahatma Gandhi.

Marriage to Indira Gandhi

This was the period when Feroze first came in contact with Indira Priyadarshini, Jawaharlal Nehru’s daughter, five years his junior. He first proposed to Indira when she was only 16, but Kamala Nehru objected, saying her daughter was too young.

Journalist Sagarika Ghose writes in her book Indira: India’s Most Powerful Prime Minister that over the next few years, as Kamala’s health deteriorated due to tuberculosis, Feroze remained a dependable friend to the Nehrus, even visiting Kamala at the Badenweiler clinic in Germany.

When Indira joined Oxford in 1937, Feroze was studying at the London School of Economics. Ghose writes that the young people fell in love then, with Indira becoming involved in the radical political movements Feroze was linked with, including the India League, led by VK Krishna Menon.

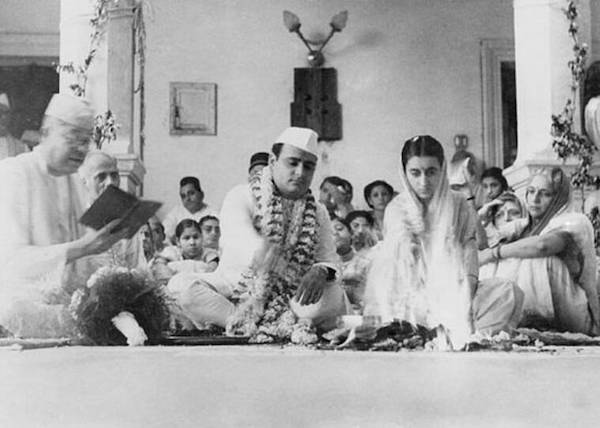

In 1941, they returned to India, both having dropped out of college and determined to get married. The Nehru family was not thrilled about Indira’s choice, as Feroze did not come from a similarly aristocratic lineage, but after Mahatma Gandhi blessed their union, the couple got married on March 26, 1942, on Ram Navami, at Anand Bhawan.

Feroze Gandhi as MP and journalist

After Independence, Feroze was elected MP from Raebareli. The Congress then had virtually no opposition. However, Feroze, even from the treasury benches, regularly raised his voice against the government and the party when he did not agree with them.

It was Feroze Gandhi who, in 1958, proved in Parliament that the Life Insurance Corporation’s (LIC) had, at the behest of high-ups in the government, invested hugely in six ailing companies owned by Haridas Mundhra, a dodgy businessman. Then Finance Minister T T Krishnamachari had to resign as a consequence of Feroze’s campaign.

Three years before that, he had exposed the financial manipulations by what was known as the Dalmia-Jain or DJ Group. His revelations led to the nationalisation of the country’s life insurance industry.

He was also the one who introduced a Private Member’s Bill making it possible for journalists to report on proceedings inside Parliament.

By now, Indira and Feroze’s marriage was deteriorating. Ghose writes that Feroze had been unfaithful, while Indira’s increased involvement with her father’s political and social life created more distance between the couple.

Journalist Coomi Kapoor, in her book The Emergency, has written that the couple’s younger son, Sanjay Gandhi, was devoted to Feroze, and “believed that his father had been abandoned and that the neglect of his well-being had led to his early death from a heart attack.”

But apart from personal differences, Feroze also disagreed with his wife politically, displaying a firmer commitment to democracy and federalism than the more authoritarian Indira.

A particularly bitter confrontation between the couple occurred over the Centre’s decision to dismiss the democratically elected Communist government of Kerala in 1959. This was when Nehru was still alive, and Indira was the Congress president. The government of EMS Namboodiripad was bringing in land and educational institutes’ reforms, which was witnessing major opposition. The central government used this unrest as a reason to dismiss the government. Among the most strident critics of this move was Feroze, who even called her wife a ‘fascist’ over this.

Swedish journalist Bertil Falk, in his book Feroze The Forgotten Gandhi, writes, “According to Janardan Thakur, well-known political correspondent: ‘It was her husband who perhaps first called her a “fascist”… The [Kerala] issue had come up at breakfast table at Teen Murti, and there had been quite a row between Indira and Feroze, with Nehru looking on very distressed. “It is just not right,” Feroze had said, “you are bullying people. You are a fascist.” Indira Gandhi had flared up. “You are calling me a fascist. I can’t take that.” And she had walked out of the room in rage.’”

On September 8, 1960, Feroze Gandhi died of a heart attack. Hindustan Times reported about his funeral that “verses from the Gita and the Ramayana, and from the Quran and the Bible were chanted. A special prayer was conducted for the departed soul by Parsi priests”.

Feroze Gandhi’s grave is in the Parsi cemetery at Allahabad, where his life had found a new direction.

Feroze Gandhi and the Dalmia-Jain Group

A backgrounder

Harish Damodaran, Feb 14, 2023: The Indian Express

Feroze Gandhi’s marathon performance, delivered on December 6, 1955, was an exposé that laid bare the financial manipulations by what was known as the Dalmia-Jain or DJ Group.

Many decades before the Hindenburg Research report, which halved the market value of the Adani Group company stocks, was a speech in Parliament that brought down India’s then third largest business house after Tata and Birla.

Feroze Gandhi’s marathon performance, delivered on December 6, 1955, was an exposé that laid bare the financial manipulations by what was known as the Dalmia-Jain or DJ Group. The revelations by the Lok Sabha MP from Rae Bareli – he happened to also be the son-in-law of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru – led to the nationalisation of the country’s life insurance industry. A more enduring legacy was the general distrust of big business that it created among ordinary Indians.

The DJ Group, like Adani, started off by building solid assets on the ground. That included Dalmianagar, an industrial town in Bihar à la the Tatas’ Jamshedpur, Ambani’s Jamnagar or Adani’s Mundra. The 3,800-acre complex had cement, sugar, paper, chemicals, vanaspati, soap and asbestos sheets-making units – even its own power house and light railways. The Group also had cement plants at Trichy (Madras), Charkhi Dadri (near Delhi), Dandot (Lahore) and Karachi, besides a biscuit factory in Patiala and collieries in Bihar’s Jharia and Bengal’s Raniganj fields. Its rise, from a lone sugar mill in 1933, was as meteoric as Adani.

The fall catalysed by Gandhi’s disclosures, similar to what Hindenburg did to Adani, was largely a product of the founder Ramkrishna Dalmia’s proclivity for speculation and unrelated diversifications. The modus operandi, in Gandhi’s words, was to “get hold of this company, get hold of that company”, jumble up their accounts and float bogus companies whose special purpose was “just to make some companies disappear” (the Mauritius, Cyprus and Caribbean Islands route hadn’t been discovered yet).

In 1946, the DJ Group bought two Bombay-based textile concerns, Sir Shapurji Broacha Mills and Madhowji Dharamsi Manufacturing Company, for a sum of Rs 3.7 crore. The same year, it also snapped up Bennett, Coleman & Co. Ltd (BCCL), publisher of The Times of India, for about Rs 2 crore.

Gandhi showed that the objective behind the purchase of the mills was to drain their reserves and invest these in the shares of BCCL: “I do not know whether this was legal…because the nature of business in which they were indulging was quite different. To the best of my knowledge, no machinery for the spinning of yarns was installed in BCCL”. Further, the day the shares were acquired, an amount of Rs 84 lakh was withdrawn by the mills from the Gwalior Bank: “What happened to the Gwalior Bank a few years later is probably known…it was liquidated.” And the mills’ auditors who weren’t happy with the goings-on – S.B. Billimoria and A.F. Ferguson – both resigned.

Equally significant were the facts brought to light on Dalmia-Jain Airways, a public-limited company with a paid-up capital of Rs 3.5 crore, floated again in 1946. Although ostensibly formed to run an aviation business, its actual purpose was to partner with another DJ Group company, Allen Berry, which was privately owned. The two jointly bought the entire stock of surplus motor vehicles and spare parts belonging to the US government in India, which it wanted to dispose of after the end of World War II, for over Rs 5.8 crore. These monies were mobilised mainly through the initial public offer by a company that, instead of flying airplanes, was engaged in the resale of American surplus vehicles after overhauling and repainting.

As it turned out, the profits from the business accrued solely to Allen Berry. The Rs 3.1 crore raised from some 25,000 shareholders of Dalmia-Jain Airways was lent out to Allen Berry. Not only did that loan remain unpaid, the partnership itself was dissolved and Dalmia-Jain Airways went into liquidation.

Gandhi also documented investments by the DJ Group-controlled Bharat Insurance Company in other group concerns, including BCCL, Allen Berry and Lahore Electric Supply Company. The monies of policyholders were used by the Group to exert control or consolidate their holdings in various companies through a maze of family trusts. In Allen Berry, for instance, the ordinary shares were wholly held by the Yogiraj Trust and Bhriguraj Trust. The funds for the two trusts to subscribe to the shares, in turn, came from Bharat Insurance. Both Bharat Insurance and Bharat Bank served as captive fund pools for the Group’s expansions and speculative investments.

On January 19, 1956, not very long after Gandhi had spoken, an ordinance was issued nationalising all the 245 insurance companies and provident societies then doing business in the country. It was followed by the establishment of the Life Insurance Corporation of India on September 1, 1956 through an Act of Parliament. “The nationalisation of life insurance is an important step in our march towards a socialist society,” declared Nehru. His daughter Indira – also the wife of Feroze Gandhi – went on to nationalise 20 private banks in 1969 and 1980.

A major difference between the Dalmia-Jain and Adani affairs is that the former group did not have a particularly great relationship with the government of the day. There was little love lost between Nehru and Ramkrishna Dalmia; Gandhi’s intervention was apparently not without the ruling dispensation’s blessings.

The DJ Group split, with the founder’s brother Jaidayal Dalmia and son-in-law S P Jain charting independent courses. They were to run leaner, and more focused, businesses. Lean and focused is, perhaps, where Adani is also headed.