Floods in Assam, North-East India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Assam

Why it is flood prone

July 11, 2024: The Times of India

From: July 11, 2024: The Times of India

From: July 11, 2024: The Times of India

This story first published on June 23, 2022 explains why Assam is devastated by floods year after year.

The state is battered by three to four waves of floods annually, thanks to its unique fluvial landscape shaped by a vast network of rivers. And one of the reasons for this phenomenon, according to experts, was the “profound impact” of the 1950 earthquake on the Brahmaputra river system, Assam’s lifeline.

The Great Earthquake

The Brahmaputra river basin falls in a high-seismic zone. According to geologists, the Indian plate has been moving northward relative to the Eurasian plate — the collision about 50 million years ago resulted in the creation of the Himalayas. Since 1900, hundreds of tremors have jolted the region, of which two were of magnitude 8 and above. The one that occurred on India’s Independence Day in 1950 remains the most devastating to date.

Called the ‘Bor Bhuinkop’ (great earthquake), the 8.6-magnitude tremor killed more than 1,500 of people in Assam and left a trail of destructions on the banks of the Brahmaputra — from its origin in Tibet to its last point in Dhubri, Assam. This mega-tectonic event and its aftershocks not only changed the course of the river but also altered its morphology.

According to Arup Kumar Sarma, a professor of civil engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati, “Earthquakes induce slope failure in the hilly terrain of the Northeast. Such slides happen in the interior area as well.”

During the 1950 earthquake, several such slides happened. “Loose earth materials [caused by slides] ultimately move to the river along with rainwater. These materials start depositing once the energy of flowing water drops after reaching flat terrain. Thus, the flow carrying capacity of the river decreases,” he tells TOI.

A 2019 research paper, titled “The Great Assam Earthquake of 1950: A Historical Review”, notes how the deposition of landslide sediments in the river bed “causes decrease in the river depth and increase in the width of the river by many times”.

The riverbed of the Brahmaputra’s tributaries such as Lohit, Dibang and Subansiri rose up to 20 feet at some places. The Brahmaputra bed itself was found to be 5-6 feet higher in Dibrugarh in the aftermath of the quake and it continued to rise until the late 1980s, contributing to Assam’s flood problem.

The annual destruction is so widespread that the state had to increase its budgetary allocation for irrigation and flood control to Rs 2,778 crore for 2022-23, up from Rs 2,452 crore for FY22

Way too much rain

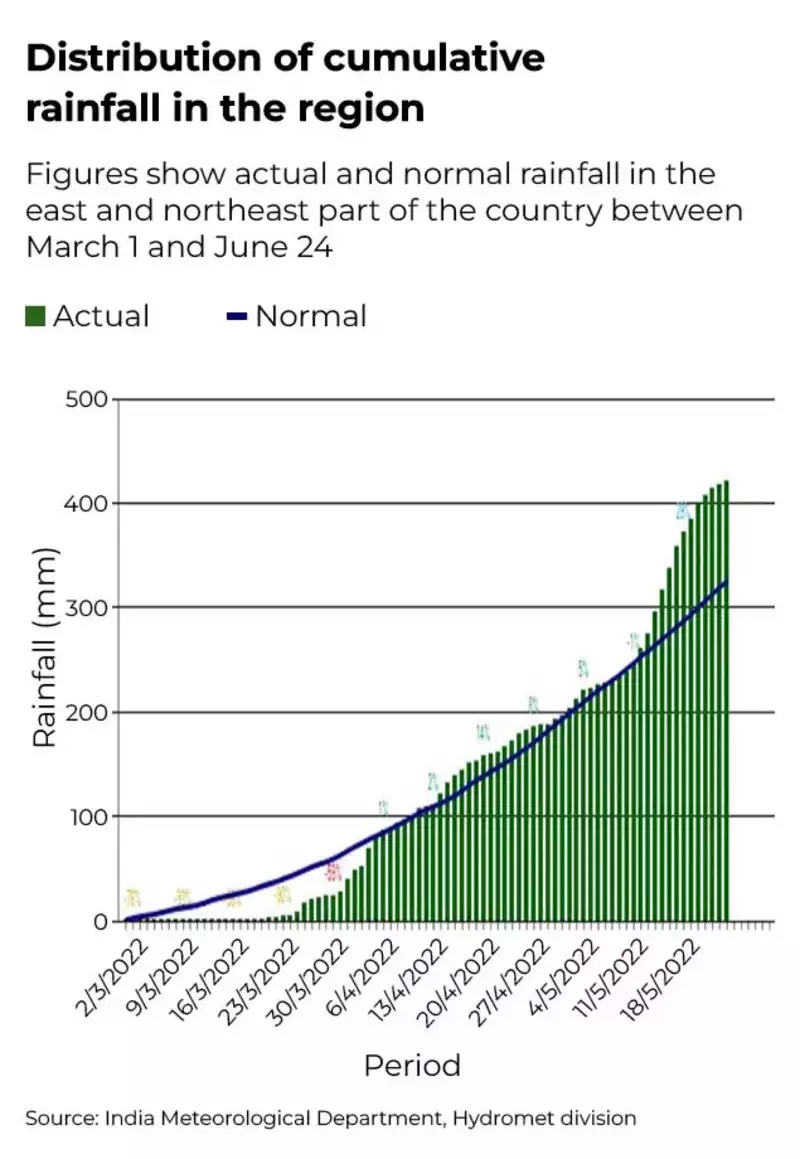

The Brahmaputra basin witnesses very high-intensity pre-monsoon and monsoon showers. Experts say that the monsoon flow in the river is generally 10 times the lean period flow.

According to the Central Water Commission (CWC) data, “Monsoon rains from June to September account for 60-70% of the annual rainfall in the basin, while the pre-monsoon season covering the period March through May produces 20-25 % of the annual rainfall”.

The low clouds brought in by the southwest monsoon pass over the 1,830 m high mountain ridges of Garo and Khasi hills of Meghalaya and enter the Brahmaputra basin, causing widespread rainfall. This, along with the snowmelt from the Tibet region, triggers floods in the Brahmaputra valley.

Climate change is making matters worse. According to a 2015 government report, Climate change projections for Assam indicate that mean average temperature is likely to rise by 1.7 - 2.2 Celsius by mid-century with respect to 1971-2000, and may cause extreme rainfall events to increase by up to 38%.

The trouble with many tributaries

Over 50 tributaries feed the two main rivers in Assam, the Brahmaputra and the Barak. All the tributaries of the valley area are rain fed, mainly the southwest monsoon. “All [Brahmaputra’s] tributaries experience a number of flood waves as per rainfall in respective catchments. If the flood of the tributaries coincides with the flood of Brahmaputra, it causes severe problem and devastation,” claims the water resources department of the Assam government.

Assam’s problem is compounded due to flash floods by the rivers flowing down from neighbouring Arunachal Pradesh and Meghalaya. For instance, in 2004 and 2014, the south bank tributaries of the Brahmaputra in lower Assam experienced flash floods of high magnitude owing to cloud burst in the catchment areas in Meghalaya.

Riverbank erosion

The bank erosion of the Brahmaputra, Barak and their tributaries is a major factor behind the annual flood problem. “The Brahmaputra, because of excessive sand deposits on its bed and along its banks, exhibits unique braiding pattern in Assam where the river bifurcates into several inter-channels and rejoins along and around numerous lateral sand bars and mid-channel islands [locally known as char-chapori],” says Prof Dhrubajyoti Sahariah of Gauhati University, who specialises in fluvial geomorphology and flood plain studies.

The lateral changes in channels cause severe erosion along the banks leading to a considerable loss of good fertile land each year, a study conducted by IIT-Roorkee on behalf of the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) pointed out.

Bank oscillation also causes shifting of outfalls of its tributaries bringing newer areas under the waters. Meanwhile, structural and non-structural flood management measures are not sustainable due to the inherent widening characteristic of the Brahmaputra.

The state government claims that the annual average loss of land is nearly 8,000 hectares. The width of the river has increased up to 15 km at some places due to bank erosion.

Vanishing wetlands

Wetlands in the Brahmaputra floodplain — numbering over 3,000 — helps in flood attenuation by acting as a natural flood reservoir. But as many as 87 wetlands are facing various forms of “disturbance”, according to a study by Prof Sahariah.

These wetlands are on the verge of extinction due to factors such as encroachment, agricultural use, road construction, human settlement, industrial use, natural decay, eutrophication and bank erosion.

For instance, Deepor Beel, a freshwater lake and a Ramsar site in the state capital Guwahati, has been facing encroachment for several years, shrinking from over 4,000 hectares in its heyday to 500 hectares currently.

What’s the government doing?

In order to control floods and erosion, the state government with central assistance has adopted various measures such as construction of embankments and flood walls, bank protection works, anti-erosion and town protection work, river channelisation with pro-siltation device and drainage improvement among others. The government claims that although these are short-term measures, it has provided “reasonable protection” to about 16.50 lakh hectares of land out of the total 31.05 lakh hectares of flood prone area identified by Rashtriya Barh Aayog (National Flood Commission).

Consider, for instance, the government’s multi-crore dredging initiative to dig out sediments from the riverbed in order to increase the water retention capacity of the river, and hence reduce flooding.

But not everyone is convinced. “Dredging is both difficult and expensive. It is much more expensive than excavation by a mechanical excavator for each unit volume of excavated material,” Dhruba Jyoti Borgohain, retired chief engineer of the Brahmaputra Board, a central government organisation tasked with managing floods in Assam, tells TOI.

He argues that dredging “is not only uneconomical in the Brahmaputra as a measure to mitigate floods but also is a futile exercise which will not pay any dividend”.

The state and Centre likely have to think out of the box and go by experts’ advice if they are serious about finding a long-term solution to Assam’s double jeopardy.

Inputs: Jayanta Kalita

As in 2024 July

“O! The mad torrents of the Luit / Where are you rushing to / With a thunderous roar / In a deathly garb repeatedly / Who are you chasing …”

Penned by the ‘Bard of the Brahmaputra’, Bhupen Hazarika, in 1968, this evergreen song is a haunting ode to the ferocity of the mighty river and the devastation it causes to Assam — one of India’s most flood-prone states — each year.

And 2024 hasn't been any different. Even though flood waters have started receding in many parts of the state, the situation continued to be grim as on July 11.

Following a report by the Assam State Disaster Management Authority (ASDMA) that said that five more people lost their lives, the toll in this year's floods, landslides, storms and lightning has now mounted to 100. Over 14 lakh people were reeling under the deluge across 25 districts.

The Brahmaputra is flowing above the danger mark at Nimatighat, Tezpur, Guwahati and Dhubri. The Barak river's tributary Kushiyara is flowing above the danger level at Karimganj town.

Dhubri is the worst-hit district with over 2.37 lakh people suffering, followed by Cachar (1.82 lakh) and Golaghat (1.12 lakh), according to the report.

The state government has been operating 365 relief camps and relief distribution centres in 20 districts, taking care of 1,57,447 displaced people.

At present, 2,580 villages are under water and 39,898.92 hectares of crop area has been damaged across Assam, ASDMA said.

Embankments, roads, bridges and other infrastructure have been damaged by flood waters in Cachar, Darrang, Dhemaji, Dhubri, Dibrugarh, Karimganj, Kokrajhar, Lakhimpur, Morigaon, Nagaon, Barpeta, Bongaigaon, Charaideo, Goalpara, Golaghat, Jorhat, Kamrup and Majuli.

On account of widespread flooding, over 11,28,398 domestic animals and poultry are affected across the state.

The nature of the annual menace

2004-18

Naresh Mitra, These flood victims don’t make news, September 4, 2018: The Times of India

From: Naresh Mitra, These flood victims don’t make news, September 4, 2018: The Times of India

Every year, floods the scale of Kerala’s deluge submerge lands and ravage homes, leaving scores dead and hundreds homeless in Assam

The devastation in flood-hit Kerala, its worst natural calamity in almost a century, has got everybody’s attention. But no one is talking about Assam, a state that faces the fury of floods year after year.

Assam suffers an average annual loss of Rs 200 crore due to floods. Like previous years, this time too, it has been battered by two waves of floods from June till the first week of August. The third wave may hit any time. Fifty people have died and more than eight lakh have been affected in 22 districts so far. Nearly two lakh hectares of crop land lies submerged, causing huge losses to farmers.

The intensity of the deluge decreased from the second week of August with the state experiencing 30% deficient rainfall. On Wednesday, three districts — Dhemaji, Golaghat and Dibrugarh — were in the grip of floods, with over 10,000 people affected.

Akan Gowala, 30, and seven family members spent 27 days in a relief camp in the Jamuguri area of flood-ravaged Golaghat. They had to leave their home, about 5km away, after the flood situation worsened following release of excess water from a hydel project in bordering Nagaland. On Monday, they returned home. “My house is halfburied in slush,” says Gowala, racked by fever, cough and skin infection. “Everyone in my family is ill. In the camp, we got food but no medicines.”

Every year, schools in lower and upper Assam turn into relief camps to house victims, hampering the students’ education. Assam State Primary Teachers’ Association president Jiban Chandra Borah says 2,800 schools were used as relief camps last year. “But as the intensity of floods is not as severe this time, 1,000 schools were used in June, July and August. In Golaghat, which is still reeling from floods, about 40 schools have been turned into relief camps,” he says.

In 2017, at least 160 people were killed in three waves of floods affecting more than 30 lakh people. Estimated cost of damage: Rs 10,000 crore. Nearly 400 animals perished at Kaziranga National Park where 90% of the park’s 430sqkm area went under water. In 2004, when Assam witnessed its worst deluge in two decades, the state suffered losses of Rs 771 crore and more than 150 people died.

The floods usually hit Assam in three to four waves between June and September. Fed by 21 major tributaries, including the Siang in Arunachal Pradesh, the Brahmaputra causes massive flooding. It has been a problem since 1950 and may explain why the state is lagging in development, which has triggered large-scale migration from rural areas to Guwahati and other parts of India. Of the 60,000 migrants from Assam who work in Kerala, more than half are from flood-prone districts. According to the National Flood Commission, 31 lakh hectares of the state’s total land area of 80 lakh hectares are flood-prone.

The devastation caused by floods is aggravated by soil erosion. Nearly 20 lakh people live on flood-protection embankments or government land after their houses and land were gobbled up by the Brahmaputra.

The annual tragedy has fuelled allegations that the Centre is not doing enough to solve the problem. Empathising with the people of Kerala, All Assam Students’ Union organising secretary Pragyan Bhuyan said, “We want to draw New Delhi’s attention to the fact that we have been asking the Centre to treat Assam floods and erosion as a national disaster so that a holistic scientific intervention is made and the sufferings of people are addressed.”

Though local groups, NGOs, students and religious bodies raise funds for flood relief, it doesn’t compare with the funds garnered for Kerala. The CAG report last year noted a 60% shortfall in release of central funds to Assam for implementing flood-management programmes: the Centre released Rs 812 crore out of its share of Rs 2,043 crore for 141 projects between 2007-08 and 2015-16.

Assam revenue and disaster management minister Bhabesh Kalita counters this with: “As of today, we have Rs 730 crore to deal with floods. Last year, the Centre provided Rs 540 crore of which Rs 198 crore is yet to be spent. This year, we got about Rs 532 crore. So, the question of the Centre not providing enough funds to Assam is not based on facts.”

On Kerala, Kalita says: “It deserved more attention because it had not faced devastation of this scale before. In Assam, people have almost learnt to live with floods. I have been witnessing floods since my childhood.

2016: July-August

The Indian Express, August 7, 2016

Samudra Gupta Kashyap

Flood fury: Why Brahmapurta’s trail of destruction has become annual ritual in Assam

The Brahmaputra, one of the mightiest rivers in the world, runs through Assam like a throbbing vein, sustaining lives and livelihood along its banks. But every monsoon, the lifeline snaps, breaks all boundaries and causes widespread misery to about 20 of the state’s 32 districts.

The Brahmaputra Valley is said to be one of the most hazard-prone regions of the country — according to the National Flood Commission of India (Rashtriya Barh Ayog), about 32 lakh hectares or over 40 per cent of the state’s land is flood-prone.

As another flood ravages Assam, displacing hundreds of people and damaging property worth crores, the question is, why does the the Brahmaputra spill over with such alarming frequency?

Experts say the problem begins with the embankments, the very structures that are meant to keep the flood waters away.

The embankments constructed along the banks of the Brahmaputra, its 103 tributaries, many of which come down from Bhutan and Tibet, and the Barak run into over 4,475 km. Many of these structures, constructed over a period of 25 to 30 years based on the 1954 recommendations of the Rashtriya Barh Ayog, show visible signs of ageing. “Though embankments don’t have specific life-spans, the ones in Assam are designed on the basis of flood data of 15 to 20 years and are supposed to remain fit for 25 to 30 years,” says a senior officer in the state water resource department. While natural wear and tear — surface run-off due to rain and rats digging burrows through the earthen structure — is one reason, most embankments across the state are also used as roads by villagers who ply motorbikes, bullock-carts, tractors, cars and trucks on them. Hundreds of families in Majuli and other flood-hit areas have made these embankments their homes by building bamboo houses on them. The gaping hole in the embankment wall at Dergaon, an Assembly segment in Golaghat district of the state, tells this story of how the embankment lost the battle to the river.

While it has been raining in different parts of the state since the first week of July, experts say the above normal rainfall in upper Assam and Arunachal Pradesh is not the only reason for the floods; environmental degradation in neighbouring hill states is part of the problem.

Only the Amazon carries more water than the Brahmaputra, one of the largest rivers in the world with an annual flow of about 573 billion cubic metres at Jogighopa, close to the Indo-Bangladesh border. But its waters carry a great deal of sediments, raising the river by about three metres in places and thus reducing its water-carrying capacity. Landslides and increasing topsoil erosion in the river’s catchment areas, particularly in Arunachal Pradesh from where come down most of the Brahmaputra’s major tributaries, have added to the river’s sediments.

As the river rages on, it eats into the soft alluvial soil of the state, eroding land along the banks. A recent study sponsored by the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) said the Brahmaputra had eroded 388 sq km of land in the state between 1997 and 2008. According to the state government, Assam has lost more than 4.27 lakh hectares — 7.4 per cent of its area — to erosion by the Brahmaputra and its tributaries since 1950. That has made the Brahmaputra among the widest rivers in the world, more than 15 km in places.

Since July 24, the Aie, a tributary of the Brahmaputra that comes down from Bhutan and flows through Chirang and Bongaigaon districts, has eroded more than 2 sq km of land in Chota-Nilibari and Dababeel villages. “The river simply swallowed our land. It was so swift that only a few families could remove the tin sheets, wooden doors and timber posts of their houses, apart from a few household items. What could we have done? You cannot remove the walls and the floor,” says Swapan Basumatary, 32, a marginal farmer who lost three bighas in Chota-Nilibari and whose family is now lodged at a relief camp in Subaijhar, Chirang district, with 46 other families.

According to the Brahmaputra Board, deforestation in Assam and its neighbouring states have accelerated the process of land erosion. According to the Forest Survey of India Report 2015, Arunachal Pradesh’s forest cover has reduced by 162 sq km between 2011 and 2015, Assam has lost 48 sq km of forest cover in the same period, Meghalaya 71 sq km, and Nagaland 78 sq km.

2017: July

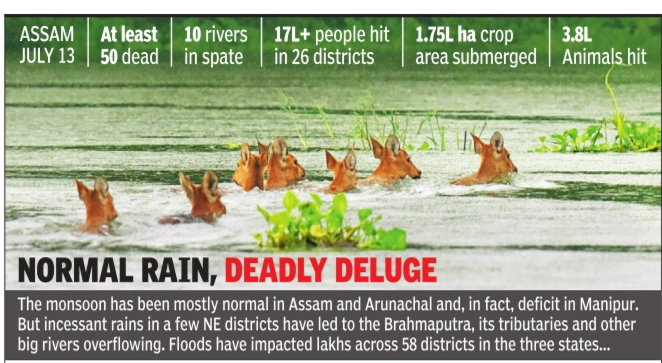

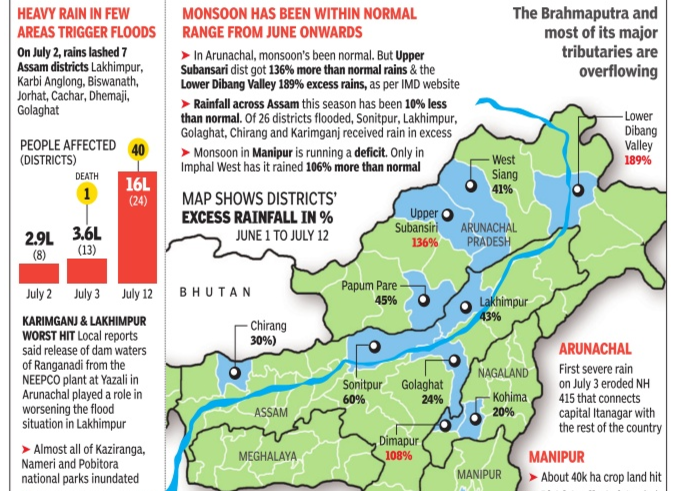

NORMAL RAIN, DEADLY DELUGE|Jul 14 2017 : The Times of India (Delhi)

The flood warning system-

Status, as in 2020

Chandrima Banerjee, December 24, 2020: The Times of India

Twenty years ago, around this time of the year, a dam breach in Tibet started a chain of events that led to the formation of a flood warning system for Assam. The collapse had led to floods in Arunachal Pradesh, after which talks between India and China on data sharing sped up. By 2002, an MoU was signed by the two countries. But India realised the need to have its own flood forecast model. It took another seven years, and the North Eastern Council and the North Eastern Space Application System (NESAC) came up with a flood early warning system in 2009.

Eleven years on, the system is in force across the state. But the loss of lives, livelihoods and property to the waves of annual floods has been unabated.

The primary data for Assam’s flood projections come from NESAC, which is under the Department of Space. “NESAC has two wings — meteorological and hydrological. Met wing scientists look at satellite imagery, collect ground information and IMD data to put together weather information. That is processed and sent to the hydrological wing. When they find there is high (river) discharge, they use hydrological models to see if it translates into low, moderate or high alert,” Biren Baishya, Geographic Information System expert at the Assam State Disaster Management Authority, told TOI. The alert is then sent to the emergency control room. “The lead time is 24 to 48 hours. It is a location-specific early warning system, so it can say which revenue circle will be affected and which river will affect it.”

The system, on paper, sounds good. More than 40% of the state’s land surface is vulnerable to flood damage and the early warning system should have helped mitigate the loss of lives. “But deaths have been increasing. One reason is the lack of awareness. We have to take every alert up to the village level — sensitisation is imperative. The other is that we have to improve the early warning system itself. Right now, accuracy is about 65-70%. There are a limited number of rain monitoring stations in Assam (there are just 68). We need more stations to improve the accuracy of our data,” Baishya said.

Another ASDMA official told TOI that the first problem, that of awareness, has to do with how bureaucratic processes operate. “We get alerts a day or two before the floods hit. We tell the districts, they tell the circle officers and the circle officers have to make sure everyone is evacuated,” the official said. The process takes time. “And sometimes, people just don’t want to leave.”

We get alerts a day or two before the floods hit. We tell the districts, they tell the circle officers and the circle officers have to make sure everyone is evacuated

The time lag, Dr Sumit Vij, an environment policy researcher who has been studying the river system for nearly a decade, said was because of the limited personnel. “India really has to invest in the northeast, Not just in terms of equipment but also human resources. They have very few human resources in Assam and Arunachal. How much can they take?” As for the data, academics and researchers pointed to two problems — a focus on river flow data at the expense of rainfall information, and the stripping away of indigenous knowledge systems.

“Our water policy starts with flowing water. It doesn’t understand falling water,” said Dr Jayanta Bandyopadhyay, retired professor at IIM-Calcutta. “Rivers originate in the atmosphere — they are susceptible to extreme rainfall. So any form of flood warning system has to come from places where extreme rainfall is expected.” In case of the Brahmaputra, he added, the flood originates around Sadiya, about 60 km from Tinsukia.

This reflects in how the river changes from Tibet, where it is called the Yarlung Tsangpo, to Arunachal Pradesh and then Assam. “Where the Yarlung Tsangpo takes a turn around the Namcha Barwa peak (in the Tibetan Himalayas), rainfall is about 350-400mm. As it flows south, precipitation starts increasing. At Pasighat, it is 4,000mm. Unfortunately, there is no understanding of how rainfall goes up 10 times from Tibet to the Assam plains,” Dr Bandyopadhyay said. And that affects the warning system for Siang, the tributary as it flows in Arunachal.

The data blind spots persist within the country as well. “There is a huge problem of secrecy of data in hydrology — I call it hydrocracy, hydrological bureaucracy,” said Mirza Zulfiquar Rahman, visiting research associate at the Institute of Chinese Studies in Delhi. “When extreme events like floods happen, there is culpability to be found. With this secrecy, you can distort and manipulate that and conveniently blame China or Bhutan. It is technological misinformation.”

The impact is for the people to endure. As of July 22, over 26 lakh people have been affected by the floods in 26 of the state’s 33 districts. Just over 45,000 have been moved to relief camps. And deaths have touched 87. “Communities in the Brahmaputra basin need accurate data. And investment not only in technological fixings but also livelihood sustainability … If a family has to move five times a year — sometimes floods come in five waves — how do they keep on fighting floods for half the year while trying to make ends meet for the other half?” Rahman asked.

And that brings up the other factor, an approach that doesn’t take indigenous knowledge systems into account.

Over 26 lakh people have been affected by the floods in 26 of Assam's 33 districts. Just over 45,000 have been moved to relief camps

“Officials often say the river needs to be tamed, like it’s an animal that has to be trained to behave the way they want. It’s a very colonial engineering kind of thinking,” said Dr Nilanjan Ghosh, director of Observer Research Foundation, a Delhi-based thinktank. “The Kosi is an example. People know how the river behaves, when the floodwater recedes and leaves rich alluvium behind … For centuries, that human knowledge has been there.”

But dams and embankments disrupt that knowledge. When land use changes, rivers behave in ways that cannot always be predicted. Like the Mising or Deori communities in Assam, who would build Chang Ghars (stilted houses) — they knew how much the Brahmaputra would swell and then go down. But now, that estimation is not possible.

“In Bangladesh, the flood process is uninterrupted. They have been doing it for ages,” said Dr Bandyopadhyay. “They live with the floods. The sediment is free fertiliser. Most years, the flood is a necessary process. Sometimes, it can be damaging — when you interfere in a way that is uninformed.”

Economic impact of floods

The economic implication of floods over the years has become more serious with the state facing floods in two or three waves. The Assam State Action Plan on Climate Change (2015-2020) said that the economic impact will be grave across different sectors and agriculture would be the most vulnerable. In 2017, the state bore a loss of Rs 2,939 crores as a result of floods. This year, the government says 21,572 hectares of crop area have been affected so far

How flood early warning system works

Satellite imagery, weather data and ground inputs are taken from weather stations

The meteorological models are studied to see if the inputs will translate into a weather event like heavy rainfall, hail storms etc

The information is then passed on to a hydrology wing. The wing looks at the data and then decides if it will lead to higher water levels

The data is then combined with that from the Central Water Commission and run through two hydrological models

The model then sends out the alert level