Girish Karnad

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

The man

Jayanth Kodkani, June 11, 2019: The Times of India

From: Jayanth Kodkani, June 11, 2019: The Times of India

There were many Girish Karnads in the culture scene. Towering among them was the Jnanpith award-winning playwright, who gave a new dimension to Indian theatre. The second was the director of films like ‘Vamsha Vriksha’, ‘Kaadu’, ‘Ondaanondu Kaaladalli’ in Kannada and ‘Godhuli’ and ‘Utsav’ in Hindi. The third was an actor who shared screen space with Smita Patil, Shabana Azmi and Naseeruddin Shah in the art cinema of the 1970s and 80s, as much as with Salman Khan in ‘Ek Tha Tiger’ in recent years.

A Rhodes scholar, he was a publisher with Oxford University Press for seven years. And then there was a Karnad who spoke his mind on issues — social, cultural or political — and often joined hands for a public cause. All this apart from public positions he held with distinction.

Some of these were parallel pursuits, which he accomplished with the ease of a motorist switching lanes on the highway. But he was, without a shadow of doubt, a key figure in theatre.

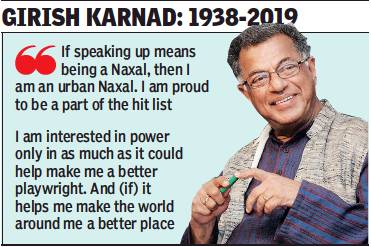

‘If speaking up means being a Naxal, then I am an urban Naxal’

Girish Karnad’s plays carried the force of present-day themes with a deeper gaze into the past. He wrote 15 plays, directed about a dozen films, TV serials and documentaries, and donned makeup for over 90 films in Hindi, Kannada, Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam. In his pursuits, he straddled two spheres: mainstream and arthouse as an actor; Kannada and English as a playwright.

As a director, he picked literary works — U R Ananthamurthy’s “Samskara”, S L Bhyrappa’s “Vamsha Vriksha” or the classic Sanskrit play, “Mrichakatika” by Sudraka — but had no qualms with the song-anddance routines of Bollywood. In his view, Hindi cinema could ward off the invasion of Hollywood because of its popular song-anddance tradition.

Seldom has India seen such multi-pronged talent. But one aspect of his personality that remains etched in Indian minds is of a resolute, clear-thinking liberal. He was amongst the most vocal critics of hardline Hindutva and police investigations had indicated that he was on the hit-list of a far-right conspiracy. “If speaking up means being a Naxal, then I am an urban Naxal,” he had said after he was seen sporting a placard around his neck at an event in Bengaluru. That was Karnad in his role as a champion of free speech.

Life and career

Jayanth Kodkani, June 11, 2019: The Times of India

One evening at dinner in their Dharwad home in 1973, Girish Karnad faced an “existential shock” as it were. His mother told his father, “And we thought we didn’t want him…” Baffled by her cryptic remark, Karnad, then 35, wanted to know more. She told him how when he was still in the womb, they thought three children would do and even visited a doctor in Pune to terminate the pregnancy. But when the doctor didn’t arrive at the clinic after a long wait, they gave up the thought and returned home. The accidental revelation, Karnad writes in his autobiography ‘Aadadata Ayushya’, came like a thunderbolt.

Such unflinching accounts of relations with family, friends and acquaintances mark his autobiography, which he dedicates to Dr Madhumalati Gune, who delayed visiting her clinic on that fateful day. He depicts life as a series of happenstances.

Much later, Karnad would say, “I am, because of my mother.” It was she who shaped his sensibilities. His mother, Krishnabai, was widowed while still in her teens and had to brave many prejudices and odds to fend for her eldest son. She then took up a nurse’s job in Dharwad where she lived with Dr Raghunath Karnad before marrying him and raising four more children. She stood up to the harsh social climate of the 1920s and even wrote a little memoir which Karnad discovered later.

At university, he longed to write poetry in English, but ended up writing plays that retold myth, legend, folklore and history to look at the present. For this, he credits scholar-poet AK Ramanujan with whom he shared a long friendship. As a director, Karnad was part of the pioneering band of Kannada new waveof the1970swithhis neorealistic films, which he said were inspired by Satyajit Ray. He was to later say that those movies were only a product of a generation associated with Nehruvian dreams.

Born into a Konkanispeaking Saraswat family, he chose Kannada and not English to write his plays. In turn, he translated them into English himself. Yet, he had his reservations about the process. “One of my plays, Agni Mattu Male, revolves around fire sacrifice. Agni, however, is a sacred fire, the same word isn’t used to refer to a house being burned down. This establishes a contrast between the sacred and the profane. I can’t do this in English.”

Karnad had a remarkable role as an administrator of many reputed institutions: director of Film and Television Institute of India (FTII); chairman of Sangeet Natak Akademi (SNA) and director of Nehru Centre in London. Actor Om Puri once recalled how when he went to FTII for admission, he was rejected because the panelists thought he didn’t look like an actor. Karnad had to veto that decision. And then he rescued Koodiyattam from near extinction in 1988 at SNA. The last guru of the art form was broke and he had no students. The bureaucracy had turned a blind eye. Karnad then helped raise a grant of Rs 5 lakh per annum and helped bring it back to life. Power, he said, should be “used only to make a better world”.

He shone brightest in theatre. In the prologue to Nagamandala (Play With A Cobra), the Story tells the Man, the Playwright: “You can’t listen to the story and leave it at that. You must tell it again to someone else.” Karnad’s muse was equally restless.

An Artist For All Seasons

Gautam Choubey, June 12, 2019: The Times of India

Artist For All Seasons Last of the philosopher entertainers, Girish Karnad’s creativity spanned theatre, cinema, television

With the demise of Girish Karnad, India may have lost the last of its philosopher-entertainers. After all, not many Rhodes scholars are known to have both acted alongside Salman Khan in a Yashraj film and hosted a popular science show (Turning Point, 1991) on Doordarshan, sharing television-time with India’s leading science communicators. These are but mere footnotes in the illustrious career of the versatile theatre and film veteran.

Bor n in 1938 in Matheran (Maharashtra), Karnad embodied the quintessence of his era – great turbulence. His art responded to the changing sociopolitical dynamics of the country, even as his own career was incessantly moulded by those very realities. In a seven-decade long career, he moved seamlessly across responsibilities and roles; from the president of the Oxford Union (1962-63) to the director of FTII (1974-75) and from the chairman of Sangeet Natak Akademi (1988-93) to being one of the architects of 1970s new wave cinema. Yet, while he scurried this creative maze with aplomb, his heart remained anchored to theatre and storytelling.

It all started with Karnad’s childhood fascination with Kannada folk theatre Yakshagana and the epic stories it dramatises. For him, the past was not an invitation to romanticise or relive the golden age myth. Rather, it was a plea to grapple with the circularity of time and the recurrence of civilisational errors. In these narratives, he found templates to understand his own time and its conundrums. The plot of Yayati (1961), inspired by C Rajagopalachari’s version of the Mahabharata and written when Karnad was only 23, explores the theme of alienation in a world where private transgressions and furtive ambitions collide with the dynamics of power and prejudice. Both Hayavadana (1971) and Naga Mandala (1988), which draw on 11th century Kathasaritsagar and Kannada folk tales respectively, survey questions of identity and salvation through debates that are remarkably contemporary. However, Tughlaq (1964) represents his most immediate and famed engagement with the ludicrous-yet-melancholic contradictions of his own age.

Karnad saw the reign of the medieval Delhi monarch Muhammad bin Tughlaq (1325-1351) as an allegory for the Nehruvian era’s bloated idealism and its tragic conclusion. The play, which was famously staged at Delhi’s Purana Qila by Ebrahim Alkazi in 1972, established the then 26-year-old as one of India’s leading lights in theatre. If the purpose of a play is to shock its audience out of their complacent stupor and awaken them to the unspoken, he attempted to do so through his irreverent reading of the classics.

With the critically acclaimed Kannada film Samskara (1970) based on UR Ananthamurthy’s novel by the same title, he made his first foray into cinema. The film was bankrolled by a rich member of the theatre group (The Madras Players) Karnad was associated with. Following a dogged battle against attempts to ban it for its alleged anti-religious theme, it went on to become the first Kannada film to bag the national award in the best feature film category. His collaboration with the likes of BV Karanth, Shyam Benegal, Vijay Tendulkar and Basu Chatterjee yielded some of the highlights of the ‘parallel’ cinema movement in India. From the white revolution in Manthan (1976) to the conflict between modernity and tradition in rural India in Godhuli (1977), his films dealt with a phase of churning and monumental change in India. Perhaps the 1984 classic Utsav, for which he joined forces with Sharad Joshi, Shashi Kapoor and Ashok Mehta, represents his most indulgent experiment with both cinema and ancient India. By the 1980s Karnad got involved with television too, playing important roles in Malgudi Days (1987) and children’s series Indradhanush (1989).

The scale and canvas of Karnad’s oeuvre mandate an important question regarding the constitution and the health of public sphere in India. What does it take to become and survive as a Girish Karnad in India? Karnad belonged to a generation of bilingual intellectuals who were creatively active in more than one language, and could therefore operate both at regional as well as national level. The likes of Vijay Tendulkar, Utpal Dutt, Habib Tanvir and Nemichandra Jain, some of whom were his close associates, wrote in more than one language. Moreover, the thriving tradition of translation in theatre of the 1960s and 1970s created a trans-regional traffic of art. Plays by Karnad, Mohan Rakesh, Tendulkar and Badal Sircar were translated and performed in several Indian languages.

Within a space of two years (1971-72), Karnad’s Hayavadana was staged in Hindi by Satyadev Dubey, in Kannada by Karanth and in Marathi by Vijay Mehta. Further, Karnad’s mentor-associates Alkazi and Karanth, who successively led the National School of Drama during its formative years, tirelessly promoted folk theatre on the national stage. In cinema too, it was a time of ferment. Censorship was milder and with the establishment of National Film Development Corporation in 1975, the state got involved in producing meaningful cinema. Simultaneously, in Doordarshan’s quest for quality content, those already active in theatre and cinema saw an opportunity. The collaboration resulted in classics such as Hum Log (1984), Buniyaad (1986), Nukkad (1986), Malgudi Days (1987) and Bharat Ek Khoj (1988).

It may, therefore, be fair to argue that it was a convergence of personal genius and favourable sociocultural milieu which produced and sustained this doyen. However, as a public intellectual, Karnad never dithered from swimming against dominant currents. He remained an astute critic of fundamentalism, intolerance and majoritarianism. In his condolence tweet, the PM too acknowledged that he was an artist who “also spoke passionately on causes dear to him”.

The writer teaches English at Delhi University