Goa: History

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Ancient history

Rock eras

Gauree.Malkarnekar, Goa’s 16 rock eras tell Earth’s story, May 22, 2017: The Times of India

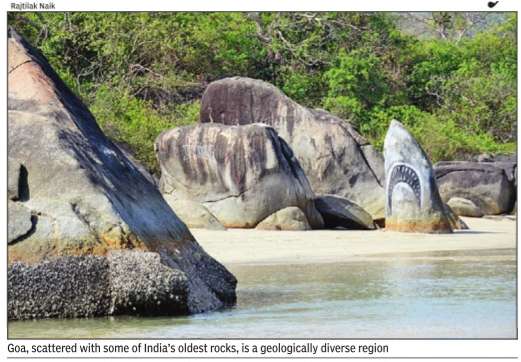

Goa may be embedded with India’s oldest rocks, trondhjemite gneiss, but the tiny state is also one of the most geologically diverse regions. If you traverse Goa’s 3,702-square-kilometre expanse, you will be walking across as many as 16 geological eras say geologists.

Trondhjemite gneiss formations found at Anmod Ghat have been recorded to be over 3.4 billion years old, followed by the gneiss formation at Palolem in Canacona. Meanwhile, the rock formations on the north Goa beach belt date back 2.5 billion years. Compare this to the fact that modern mammals as wells as hominoids appeared on Earth only 65 million years ago.

Scientist Nandkumar Kamat says we need to create thematic ancient pre-cambrian geological parks to spread knowledge about the existence of this natural heritage, not just at Anmod Ghat and Palolem, but also at “Dudhsagar/Colem/Castelrock and Chandranath/ Paroda”, where important rock formations have been identified

The age of the granites found at Dudhsagar and Chandranath are believed to be 2.6 billion years old.

The gneiss and schists have folded several times and their merging with other newer rocks has led to different formations.“These trondhjemite gneiss rocks have undergone a change from ingenious rocks to metamorphic rocks over a long period of time due to heat and pressure. At many places, granite rocks have turned into gneiss because of metamorphism,” says geographer F M Nadaf.

The colonial era

An overview

Valmiki Faleiro, July 11, 2023: The Times of India

Portugal, although puny with a population of just over a million and nothing noteworthy about her ocean-going traditions, was the first European nation to chart a sea route to Asia. The fall of Constantinople (now Istanbul) to the Ottoman Turks on May 29, 1453 made Portugal feel the need to open a new battlefront with the Ottoman Empire by joining forces with the mythical Rei Preste João (King Prester John of Abyssinia, today’s Ethiopia), for which naval power was a prerequisite.

Until then, Portugal only had half-decked sailboats and sailors who were unable to navigate out of sight.

A far-sighted Portuguese prince, Dom Henrique, better known as Henry the navigator, invested some of his own wealth and that of the templars into shipbuilding and navigation. He launched a maritime school at Sagres on Portugal’s southwestern cape of São Vicente facing the Atlantic. (Modern historians call Sagres a myth. In 1960, the Portuguese in Goa built a monument — a sextant with a mariner’s globe — to commemorate 500 years of the Sagres school for navigation at Campal in Panjim. Portugal’s vessel to commemorate the fifteenth-century voyages of discovery was named Sagres — she docked at Mormugao, Goa, in the mid-1990s amidst howls of protest by local freedom fighters.)

At Sagres, or some such place, Portuguese sailors were trained in cosmology, cartography, math, medicine and shipbuilding by hired Arabs, Jews, Genoese and Moroccans.

Henry the navigator sponsored annual maritime expeditions to explore and map the west coast of Africa, to establish provisioning points en route and to constantly modify and improve the sturdiness of his sail ships. He died in 1460. After a lull of two decades, his nephew, King João II (1481-95), picked up the threads in 1480. In 1487-88, Bartolomeu Dias made the historic rounding of the much-feared Cape of Torments, where Adamastor, the tempestuous sea devil, was believed to swallow sail ships and turn white men black.

With Portugal’s maritime conquest, the Cape of Torments became the Cape of Good Hope. It was then that King João II conceived the Plano da Índia, a plan entailing the search for a sea route to India. The fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans had closed the land route to Asia and the trade of spices, silks and other Asian merchandise was now a monopoly in the hands of seafaring Arabs and Venetian merchants, who profiteered at the cost of Europe. Portugal would soon emerge a European leader in maritime discovery — and of the lucrative Asian trade!

The Portuguese were the first to arrive in India. Discoverer Vasco da Gama dropped anchor near Calicut in May 1498, long before the Mughals stepped into India. Calicut was, coincidentally, the hometown of India’s future defence minister, Vengalil Krishnan Kurup Krishna Menon — the principal backstage actor in the 1961 Operation Vijay, which evicted the Portuguese after more than four-and-a-half centuries in India.

The Portuguese discovery of a sea route to India was an epoch- defining moment in the history of mankind. It would open the gates to an ‘Age of Discoveries’, lead to lands hitherto unknown to the European world — in Africa, Asia, Australia and, accidentally, the Americas — and spur a commercial revolution, the initial indicators of globalisation and a world economy. It was to change the world’s history, economics and politics. It had an underbelly too: it would lead to colonialism and spur slavery.

Interestingly, Portugal’s prideful narrative of the ‘Age of Discoveries’ makes no mention of the burgeoning and highly profitable African slave trade that continued well into the nineteenth century. Film-maker and journalist Ana Naomi de Sousa writes: “Until now, there has never been a single explicit reference, memorial or monument in Portugal’s public space to its pioneering role in the transatlantic slave trade, nor any acknowledgement of the millions of lives that were stolen between the 15th and 19th centuries. There is also a deafening silence on the cruelty and brutality that the Portuguese inflicted to achieve the domination of their trading posts and colonies.”

When it arrived at the shores of south-west India, Portugal was barely out of the late Middle Ages and on the threshold of the early Renaissance. Lisbon, established circa 1200 BC, was the oldest European capital city — older than Madrid, Rome, Paris and London. The Indian civilisation was far more ancient, second only to Mesopotamia and Egypt, older than the civilisations of Maya/ Mexico, China and Andes (Aztec, Inca); and all of those, much older than Europe.

The Portuguese set up spice-trading bases in Cochin (Kochi) and Cannanore (Kannur) on the Malabar coast. They raked in such giddy profits that the envious European royalty nicknamed their king, Manuel I, the Fortunate. Their Asian capital, initially in Cochin, was shifted to Goa in 1530, fifteen years after he died, thanks to Afonso de Albuquerque, the Portuguese governor in India from 1509 to 1515. Albuquerque had conquered the Cidade de Goa (City of Goa) in 1510, and it appeared as though he had fallen in love with the place because he wanted it to be Portugal’s Asian capital.

Cochin was eminently suitable to be the capital of Portugal’s littoral empire in the east. It had the best and most naturally protected harbour on the Malabar coast. It provided fine hardwood and its shipyards built worthy vessels that enabled the Portuguese to sail in Asia and on the Cape route.

Carracks and galleons built here would earn a reputation as the most seaworthy of the Carreira da Índia (vessels of the Portuguese on the India–Portugal sea route). A series of lagoons and creeks connected Cochin’s port to the pepper-producing districts. expectedly, therefore, Cochin emerged as a major entrepôt after the Portuguese dug in, and a large Casado community (Portuguese men married to native women) settled there. owing to its proximity to important trade points like the Coromandel, Orissa, Bengal, Pegu (Burma), Siam (Thailand), Malacca (Melaka), China and the far East, Cochin was better located than Goa for trade — and thereby as the principal base in India.

In 1510, together with the city of Goa, Albuquerque conquered the island taluka of tiswadi (Ilha de Goa) with its neighbouring islands of Chorao, Divar and Jua (Santo Estevam). The talukas of Bardez, Salcete and Ponda were also captured but were soon retaken by Bijapuri reinforcements. A see-saw contest between the Adil Shahis of Bijapur and the Portuguese in Tiswadi followed over the next forty-two years for Bardez and Salcete, which finally came into the definitive possession of the Portuguese in 1543.

The three talukas of Bardez, Tiswadi and Salcete (Mormugao was detached from Salcete as a separate taluka only at the fag end of the 19th century) were called the ‘old Conquests’. All were coastal talukas abutting the sea. The vast majority of the population in these three talukas was converted to Christianity by the early 17th century — those who resisted conversion were persecuted in a variety of ways: their properties were confiscated and they were evicted.

With their gods, idols and faith, such Goans (many converted ones too, escaping the rigours of the Inquisition) resettled in areas beyond Portuguese control (in the remaining talukas of what is today Goa, in the Deccan areas from Kolhapur to Belgaum, and in coastal Karnataka and Kerala).

Force and coercion, although prominently employed in the conversion of natives, were not the only reasons for the natives embracing a new faith. The Switzerland-based, Goan-origin, retired, chemical engineer and author Bernardo Eelvino de Sousa, has skilfully adopted a case-study approach, indicating a varied and complex set of reasons for religious conversion in Goa through specific cases of individual and group conversions.

More than 250 years later, in the second half of the 18th century, the Portuguese acquired the rest of Goa’s talukas — Canacona, Quepem, Sanguem, Ponda, Bicholim (known earlier as Sanquelim), Sattari and Pernem — and these were collectively called the ‘new Conquests’. Save Pernem at the northern end and Canacona at the southern extremity of Goa (and a very tiny part of Quepem), which abutted the sea, all the new Conquest talukas lay in the hinterland.

The ‘new Conquests’ surrounded the ‘old Conquests’ and served as a buffer against attacks over land. The Portuguese did not follow proselytization in the new Conquests, which remained predominantly Hindu. However, there was an odd aspect to the old and new Conquests. The seven new Conquest talukas accounted for 80 per cent of Goa’s geographical area but housed only 27 per cent of its population, mostly Hindu.

Most of the major Hindu temples like those of Mangesh, Mahalsa, Shantadurga, Kapileshwar and Ramnath had been shifted to the new Conquest taluka of Ponda (a non-Portuguese area then) at the height of religious persecution in the 16th–17th centuries.

(There is a common misconception that the temple of Lord Naguesh at Bandora in Ponda taluka may have been shifted from Nagoa in Salcete taluka. This is not so. The Naguesh temple is the only temple originally from Ponda taluka which predated the Portuguese and is mentioned in the copper plates of Vim’n Mantri, circa 1350 CE.) The bulk of Goa’s mineral-ore wealth was in the new Conquest talukas of Sanguem, Quepem and Bicholim.

Excerpted with permission from Goa, 1961: The Complete Story of Nationalism and Integration (published by Penguin Random House)

Football: 1883-1951

Marcus Mergulhao, Dec 19, 2021: The Times of India

PANAJI: In 2012, when then chief minister Manohar Parrikar declared football as the state sport, a first for any state in India, everyone applauded the decision. But in reality, it really shouldn’t have taken so long for the government to realise the influence of football on Goans.

Football, after all, has been more than just a sport ever since Fr William Robert Lyons, a visiting British priest, first brought the game to Goa in 1883.

Throughout the twentieth century, football remained an important part of expatriate relations with Goa as the best teams from Bombay, now Mumbai, were touring the state, then under Portuguese rule.

St Mary’s College landed here as early as 1905 to play friendlies against Panjim Boys, while by the 1940s, prominent teams like Young Goans and BEST were also making their presence felt.

The Portuguese knew what football meant to Goans, so during the crucial decade prior to Liberation when pressure was building on the colonial powers to relinquish hold over foreign lands, the Salazar regime did everything it could to convince Goa they were in good hands.

Football was their biggest tool.

“The Portuguese made some last-ditch attempts to create in Goans an awareness of the benefits of European rule and of their ties to the Iberian state. Football proved to be an important means of attempting to promote this cultural association and of highlighting the effectiveness of Portuguese administration,” James Mills notes in, ‘Colonialism, Christians and Sport: The Catholic Church and Football in Goa, 1883-1951’.

Starting from 1955, tours of major teams from around the Portuguese empire were arranged, with Ferroviario de Lourenco Marques being the first to play here. The Mozambique-based club attracted a crowd of 20,000 for each of its two matches.

Four years later, Pakistan’s leading football team, Port Trust Club of Karachi, landed here, “symbolising the solidarity of two anti-India footballing nations”. But the most famous of them all was, no doubt, the visit of European giants SL Benfica in 1960.

“Benfica's tour of Portuguese Goa in 1960 was seemingly intended to remind indigenous subjects of their imperial connections and responsibilities,” Todd Cleveland wrote in, ‘Following the Ball: The Migration of African Soccer Players Across the Portuguese Colonial Empire’.

Significantly, governor-general Vassalo e Silva was present for two of the three games that Benfica played in Goa.

Football was also provided pride of place as the sport was separated from others, governed by the Conselho de Desportos da India Portuguesa which, as its name suggests, was a general sports council.

Instead, the Associacao Futebol de Goa (now Goa Football Association) was formed on December 22, 1959.

Freedom struggle

1583: Cuncolim Revolt

Govind Maad, Dec 20, 2021: The Times of India

Cuncolim observed the 438th anniversary of the Cuncolim Revolt of 1583 earlier this year. Centuries later, the seminal historical event may finally find its way into the academic curriculum of high schools, as has been announced by CM Pramod Sawant.

It was five villages from South Goa — Cuncolim, Ambelim, Assolna, Veroda and Velim — that waged a war against the Portuguese colonists, resulting in bloodshed and non-payment of taxes in protest — hundreds of years before Gandhi was to lead satyagraha for non-payment of salt tax to the British.

“At Bardez in North Goa, about 300 Hindu temples were razed to the ground. In 1583, the Portuguese army destroyed several Hindu temples at Assolna and Cuncolim,” a historical account states. On July 25, 1583, five Jesuits accompanied by one European and 14 native converts went to Cuncolim to erect a cross and select ground for building a church. Hordes of villagers, armed with swords, daggers, spears and sticks, brutally killed the invading party.

Women freedom fighters: 1946 onw

Mackelroy Barreto, Dec 19, 2021: The Times of India

PANAJI: Most recognised freedom fighters may be male, but the story of the other half is no less stirring, wrote Manohar Rai Sardesai.

“For young women to even stand up to those Portuguese officers and those ‘pakle’! Do you know how daring that was? Even 10 women were like a hundred of them. Look at those times, women couldn’t even step out,” says 89-year-old Naguesh Karmali.

And he would know, he was in the thick of things. Karmali was sentenced to 10 years in jail on September 15, 1954, serving five at Aguada and Reis Magos before being freed.

Surrounded by towering books at his Ribandar home, he talks of times when forest-dwellers between Quepem and Rivona sheltered a rag-tag group of freedom fighters who were criss-crossing villages, rallying for liberation.

The growing involvement of women in politics is linked to Goa’s liberation struggle. The Portuguese rule helped improve the status of women in society by abolishing Sati and polygamy. They could remarry and there was emphasis on education. Emboldened with their place in society, it wasn’t long before women turned the tables on the colonists.

Accounts suggest that Dr Ram Manohar Lohia’s meeting on June 18, 1946, demanding civil liberties spurred women to take up the liberation struggle. They turned up in large numbers at Margao and were then seen regularly at meetings, protests, satyagrahas, roused at times by the patriotic fervour brought on by fierce discussions expressed inside homes.

Any talk about Goa’s Liberation movement and you will find that the role played by women is rarely glorified. The fact is that there is a whole pantheon of women who faced unimaginable physical and mental torture in their quest for a free homeland.

Most of the freedom fighters were young women across caste and classes. They hated the Portuguese regime and were inspired to free Goa.

Consider young Vatsala Pandurang Kirtani who stood up to the Portuguese police commandant at the meet at Margao on June 18, 1946. He questioned her for raising the slogan ‘Jai Hind’ in defiance of his direct orders. The fearless lass turns around and says, “Just as the words ‘Viva Salazar’ fill you with pride, so does ‘Jai Hind’ galvanise my spirit.” She was promptly arrested. A testimony to the bravery of Goan women freedom fighters can be found in the codices of the infamous Tribunal Milatar Territorial — the military court established by the Portuguese in Panaji to prosecute those involved in the freedom struggle.

The military court manuscripts maintained by the archives department make for a most insightful reading, especially stirring accounts of women freedom fighters and the persecution they faced from the Portuguese. A woman freedom fighter went deaf in one ear from the beating she received, according to military accounts.

Among the more prominent is Sudha Madhav Joshi, popularly known as Sudhatai, from Mardol, Ponda. Sudhatai was arrested at the Mapusa garden square for carrying the Indian flag. She was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment and slapped with a penalty of 20 escudos per day, with an additional suspension of all her political rights for 20 years, including internment for two years on grounds of security measures. The allegation-- attempting to entice the local population to commit crimes against the Portuguese government.

Prema Purab from Pissurlem, Sattari, helped to carry arms from Belgaum, through the forests, to Mohan Ranade in Goa. On one such mission she was fired at by the Portuguese police and a bullet hit her in the leg. The injured Purab escaped to a mining area belonging to Dayanand Bandodkar, from where she managed to get into a mining truck and made it across Goa’s border to Belgaum to receive treatment.

The Braganca sisters also feature in the annals of Goa’s struggle — Dr Beatriz and Berta de Menezes Braganca, daughters of late Luis de Menezes Braganca.

Berta was a leading figure in the struggle and had defied the ban on civil liberties by speaking publicly. She strode alongside her uncle T B Cunha at protest marches and speeches in South Goa. Berta also founded a fortnightly in 1958 in Bombay called ‘Free Goa’ and she toured India demanding military action against the colonists. She was also chief of the Goa wing of the Indian National Congress. At a meeting planned on June 30, 1946, in Margao, she and Cunha were prevented from speaking. She boldly took on the police and both were shoved into a car and abandoned by the roadside at Chandor.

Prabhakar Sinari, who was deeply involved with the militant struggle to free Goa, says, "The women contributed a lot to Goa's freedom movement. Despite women being suppressed in our society in those days, they came forward. Their participation was not negligible. Some of them were even manhandled by the Portuguese policemen, but this did not deter these women.” The Portuguese certainly did not hold back. Women were tortured, regularly imprisoned, subjected to humiliation, interrogation, intimidation and even to third-degree methods.

In the face of all political adversity and bullying by colonial forces they are known to have stood their ground.

Shashikala Hodarkar was arrested and sentenced by the military court for possessing ‘subversive literature’ while proceeding from Poinguinnim to Margao. She operated from across Goa’s border under the guidance of Peter Alvares, secretary of the National Congress Goa. This meant she would have had to frequently trek through forests to access border areas.

Inspired by Sindhu Deshpande, Hodarkar offered satyagraha on February 17, 1955, at Margao and was arrested for distributing pamphlets. She was shown physical torture that male political prisoners underwent (beating and laying on ice) to dissuade her campaigns, which only strengthened her resolve.

The quest for freedom meant women were also forced to live underground like their male counterparts. Sometimes they ended up being imprisoned at the same time as their husbands, which meant their children had to be looked after by extended families. Vatsala Kirtani, who was arrested on June 18, 1946, after she stood up to deliver a speech at the same meeting organised by Lohia, also finds mention in the manuscript. After she was arrested, a group of 40 women marched to the station demanding her release. The face-off came to a boil and the police relented since all the women wanted to be arrested along with Vatsala. Even though she was officially released, she refused to leave and had to be physically hauled out of prison by the same commandant.

Libia Lobo Sardesai invokes immediate connection with Goa’s Liberation struggle for running the underground radio station, ‘Voice of Freedom’. Libia is known to have made repeated announcements of the ultimatum to the last governor-general to surrender to the Indian Army.

Other names that feature in the struggle for Goa’s Liberation include women within and outside the state who actively participated to liberate Goa---Maria Joaquina Calista Araujo, Kishoribai Harmalkar, Srimati Divkar, Laxmibai Paingunkar and Suryakanti Faldesai from Canacona, Dr Laura D’Souza, Kumudini Paingunkar and Sindhu Deshpande from Poona, Shalini Lolienkar, Shanta Hede, Shashikala Almeida, Mitra Bir, Rajani Naik and Lalita Kantak.

Sharada Padmakar Savaikar was 16 when she was arrested by the feared police officer Casmiro Monteiro on suspicion of murdering a local from her village of Savoi-Verem. He was a known Salazar sympathiser. Her father and three brothers were imprisoned and continuously tortured. Savaikar spent two years in jail before being produced before the military court, where she called out Monteiro’s cruelty by showing the judge the scars she sustained from the beatings.

She lost her teeth in the beating but refused to buckle under Monteiro’s threats of “you’ll rot in prison for 14 years”, and instead told him she was ready for it. She maintained her innocence and did not betray any of her members.

In a strange twist, release orders for a Sharada Shirvaikar came through, and the Portuguese police confused the names and released her instead.

Celina Olga Moniz from Saligao was arrested on January 26, 1955, for carrying the Tricolour. At the Panaji jail she was severely tortured and released only in October.

She is known to have helped the underground nationalist movement in Goa and neighbouring states to provide support and financial assistance. Most of her associates, who were involved with the original planning of Goa’s freedom struggle at a meeting held at the residence of Dr Jose Francisco Martins in June 1954, were arrested and tried at the military court. Moniz is the recipient of Tamrapatra from the central government, one of the highest honours for political prisoners.

1947: the Azad Gomantak Dal

Gauree Malkarnekar, Dec 19, 2021: The Times of India

PANAJI: In the middle of the 20th century, Latin American revolutionaries like Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara attained cult-like status for their guerilla tactics and exploits against oppressive state machineries. But on the other side of the planet, in tiny Goa, there was no acclaim and adulation — only struggle — for the young guerillistas who, against all odds, battled the formidable, entrenched and brutal Portuguese State.

Not only were they fighting a woefully David and Goliath battle within the state’s borders, there was no support from the Indian government either. In fact, New Delhi only added to the revolutionaries’ problems.

Over the length and breadth of the subcontinent, Mahatma Gandhi’s ideology of non-violence had taken over the conscience of an entire people, and armed resistance was seen as anathema. “After India got its independence, the Indian government was too worried about the world’s opinion,” says Prabhakar Sinari, 93, who now resides in Caranzalem with his wife Vilasini. “They were worried what the US would think of it, and no support was given to us. In fact, the Indian government threw hurdles in our path. At the border, they would stop my colleagues and take away the ammunition they were trying to smuggle into Goa. There were people willing to give us donations, but Customs would block them.”

It was exactly a year after Ram Manohar Lohia’s civil disobedience movement in Margao that the militant Azad Gomantak Dal was formed, on June 18, 1947. Seven young men —Sinari, Dattatreya Deshpande, Betu Naik, Tukaram Kankonkar, Jaiwant Kunde, Narayan Naik, and leader Vishwanath Lawande — pledged their life to liberate Goa through guerilla tactics, at the Shree Shantadurga Temple at Kunkoliem, near Mardol, Ponda.

Azad Gomantak Dal, or AGD, was born after the youngsters witnessed the ruthlessness non-violent protestors were subjected to by the Portuguese. But the revolutionaries had to start from scratch, from learning to fire rusted pistols for the first time in the midst of a siege, to planning heists on the colonisers’ treasury to get funds for ammunition.

“Our first target on the night of July 21, 1947, was the treasury building of Fazenda at Mapusa, where we hoped to lay our hands on some cash for our activities,” said Sinari. However, the lone sentry at the Fazenda raised an alarm, and their attempt failed. But with one policeman badly injured, it sent shock waves through the rank and file of the Portuguese administration.

The botched attempt made AGD realise they required better training. Soon, a former Indian Navy officer, Mukund Dhakankar, trained the young revolutionaries in the use of firearms and explosives. Now far better equipped, the AGD set their next target — the Banco Nacional Ultramarino in Panaji, the Portuguese bank for overseas finance.

“The action was to take place at Porvorim,” Sinari recalls. “Unfortunately, in the bus, the bank officer who was carrying the cash bags saw us signalling to our friends and pushed the money bag under the seat of a young girl. We were only able to snatch the other bag, which was mostly filled with cheques and very little cash. After this raid, the police identified us one by one and at the age of just 14, when I was a minor, they pronounced a sentence of eight years.”

In prison at Aguada and later Reis Magos, AGD members were subjected to unspeakable torture. They were lashed with hippo skin whips, starved, kept in unhygienic conditions, put through solitary confinement, and crammed into a cell with not enough space for everyone to sleep at night.

Sinari managed to escape prison four years into his sentence, and returned to the movement to find many more young men had enrolled with AGD.

When the AGD made Pernem its base, Sinari said the region was as good as freed from Portuguese rule, as the colonisers’ officers were terrified to step there for fear of being attacked. The AGD was also actively involved in helping free Daman and Diu from Portuguese clutches.

“We received support from the Indian government only at the fag-end of the struggle for Goa’s freedom. We would lay road mines, traps and blow up roads and railways crucial to the Portuguese. We had learnt to conceal the land mines so well that the Portuguese officials could rarely tell where one was waiting for them,” he said.

When Liberation neared, Sinari recalled how the AGD came to the Indian Army’s aid by clicking photographs of Goa’s terrain and identifying land mines to help their advancement within the then Portuguese-occupied region.

“During those years with AGD, many of our young colleagues were martyred,” said Sinari, the only surviving member of the group. “Our families were harassed, my mother was left to starve with all three sons away in prison or working for the Dal underground. Some men lost their limbs or eyes. But when Goa was finally liberated, it was a proud moment. Many had said the Portuguese had been here for more than 400 years and that they would never leave. But we showed them that we had not gone to jail for nothing.”

Much later, Sinari served as Liberated Goa’s first Goan inspector general of police (IGP), and then as assistant director of India’s intelligence agency R&AW, looking after then PM Indira Gandhi’s security. But it was decades later, in the 1980s, that the AGD finally got official recognition from the state it helped free.

1787-1955: Monuments

Dec 20, 2021: The Times of India

SENSE OF HISTORY

Many laid down lives in Goa’s quest for freedom. These memorials serve as a reminder

AGUADA JAIL

At the height of Goa’s independence struggle, freedom fighters were imprisoned at the 17th century Aguada fort, constructed by the Portuguese to guard against the Dutch and the Marathas

PATRADEVI MEMORIAL

As a peaceful protest, several youngsters entered the ‘Portuguese territory’ at Patradevi but the colonial police opened fire and at least 30 satyagrahis lost their lives on Aug 15, 1955

PINTO’S REVOLT MEMORIAL

Fr Caetano Vitorino de Faria, father of Abbé Faria, masterminded the Pinto Revolt or Pinto Conspiracy against Portuguese rule in Goa in 1787. The Memorial is in the heart of Goa’s capital city LOHIA

MAIDAN

The site where Dr Ram Manohar Lohia broke the Portuguese ban on public meetings on June 18, 1946 in Margao is today the Lohia Maidan

1961

Accession to India

February 13, 2022: The Indian Express

Goa became a Portuguese colony in 1510, when Admiral Afonso de Albuquerque defeated the forces of the sultan of Bjiapur, Yusuf Adil Shah. The next four and a half centuries saw one of Asia’s longest colonial encounters — Goa found itself at the intersection of competing regional and global powers and religious and cultural ferment that would lead eventually to the germination of a distinct Goan identity that continues to be a source of contestation even today.

By the turn of the twentieth century, Goa had started to witness an upsurge of nationalist sentiment opposed to Portugal’s colonial rule, in sync with the anti-British nationalist movement in the rest of India. Stalwarts such Tristão de Bragança Cunha, celebrated as the father of Goan nationalism, founded the Goa National Congress at the Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress in 1928. In 1946, the socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia led a historic rally in Goa that gave a call for civil liberties and freedom, and eventual integration with India, which became a watershed moment in Goa’s freedom struggle. At the same time, there was a thinking that civil liberties could not be won by peaceful methods, and a more aggressive armed struggle was needed. This was the view of the Azad Gomantak Dal (AGD), whose co-founder Prabhakar Sinari is one of the few freedom fighters still living today.

As India moved towards independence, however, it became clear that Goa would not be free any time soon, because of a variety of complex factors. The trauma of Partition and the massive rupture that followed, coupled with the war with Pakistan, kept the Government of India from opening another front in which the international community could get involved. Besides, it was Gandhi’s opinion that a lot of groundwork was still needed in Goa to raise the consciousness of the people, and the diverse political voices emerging within should be brought under a common umbrella first.

There were also questions with regard to the mode of protest to be followed. In her thesis ‘Goa’s Struggle for Freedom, 1946-61: The Contribution of National Congress Goa and Azad Gomantak Dal’, historian Dr Seema Risbud highlighted the dichotomies within the groups fighting for freedom in Goa, and argued that satyagraha had its limitations against a totalitarian regime. This point appears to have been validated by the success of the militant role played by the AGD in the liberation of Dadra and Nagar Haveli, another Portuguese enclave (albeit with the covert support of Indian authorities, as some have suggested).

Nehruvian dilemma

It was apparent that Nehru was prepared for the long haul in Goa, perhaps trying to exhaust all options available to him given the circumstances that India was emerging from, and where he was headed in shaping India’s position in the comity of nations. Portugal had changed its constitution in 1951 to claim Goa not as a colonial possession, but as an overseas province. The move was apparently aimed at making Goa a part of the newly formed North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) military alliance — so the collective security clause of the treaty would be triggered in the event of an attack by India or any other nation — but this was not acceptable to other NATO member countries.

Nehru saw it prudent to pursue bilateral diplomatic measures with Portugal to negotiate a peaceful transfer while, at the same time, a more ‘overt’ indigenous push for liberation — one that would strengthen India’s moral argument — gathered momentum. His 1955 Independence Day speech — cited by Modi in Rajya Sabha — criticising the satyagrahis who were trying to cross the border did demoralise the diverse pan India group of liberation fighters comprising socialists, communists, and the R S S. But the firing incident also provoked a sharp response from the Government of India, which snapped diplomatic and consular ties with Portugal in 1955.

The obvious question that arises is, if things had reached such a stage in 1955, why did Nehru wait until December 1961 to launch a full-scale military offensive, even though India continued to raise the issue of Goa at various levels and fora?

D P Singhal, who was a political scientist at the University of Queensland at the time, provided a clue in his paper ‘Goa: End of An Epoch’, published in The Australian Quarterly in March 1962. With India firmly established as a leader of the Non Aligned World and Afro Asian Unity, with decolonisation and anti-imperialism as the pillars of its policy, it could no longer be seen to delay the liberation of Goa. An Indian Council of Africa seminar on Portuguese colonies organized in October 1961 heard strong views from African delegates who argued that India’s policy of going slow on the Goa question was hampering their own struggles against the ruthless Portuguese regime. The delegates were certain that the Portuguese empire would collapse the day Goa was liberated.

The rest, as they say, is history. Goa was liberated on December 19, 1961 by swift Indian military action that lasted less than two days.

The debate in 2022

Politics needs to be charitable to history, because at some point it would be put to the same scrutiny and judgment as it becomes history itself.

Sinari, the lone surviving member of the AGD, whose sense of history and political instincts have not been blunted by age and failing health, says attempts at political point-scoring around incidents that took place in a certain historical context more than six decades ago, only diverts attention and focus from pressing current issues.

Goa has seen 60 years of eventful liberation and successful amalgamation in the Indian Union. It is more important for it to look ahead to its future than to rapidly receding, increasingly dim images in the rear-view mirror.

‘Voz de Liberdade’/ ‘Goenche Sadvonecho Awaz’ radio

Newton Sequeira, Dec 19, 2021: The Times of India

PANAJI: As one zips across the picturesque Western Ghats towards Belagavi, with Adele singing about hope and silence in the waters, it’s easy to forget that a secret radio station once broadcast hope from the very dense woods that now pass by in a blur.

For a little more than six years, amid venomous snakes, blood-sucking leeches and intrusive insects, two young Goans sent out fiery bulletins and notions of freedom to thousands of their compatriots. From November 25, 1955, the couple — Libia and Vaman Sardesai — used radio transmitters and made the forests their home till Goa was free.

The radio station was known as ‘Voz de Liberdade’ and ‘Goenche Sadvonecho Awaz’, which meant ‘Voice of Freedom’, and its primary aim was to sustain the morale of Goans and demoralise the Portuguese.

Libia Lobo Sardesai grew up around the streets of Crawford market in then Bombay, where she saw how those fighting for freedom were crushed to death. The fighting spirit in her was rekindled when her then law college professor and later noted jurist, Ram Jethmalani, said that India couldn’t be called independent and free as long as Goa remained a colony.

She got her chance in 1954, after Dadra and Nagar Haveli was liberated from the Portuguese. The spoils of this capture were two radio transmitters, which were used to start an underground radio service to help free Portuguese-occupied Goa.

“The purpose of the broadcast was four-fold — to sustain the morale of the people, to demoralise the Portuguese, to counter the lies of the Portuguese, and to show that it was not just a struggle about Goa, but about all other anti-colonial struggles,” says Libia as she takes her mind back to 1955.

From the first broadcast in November that year to the last message heralding freedom on December 19, 1961, the Sardesai couple kept alive the Voice of Freedom. The duo sent out two broadcasts every day, working 18 hours a day while eluding wild animals and Portuguese soldiers.

“First we were on the Maharashtra border, closer to Sawantwadi, in no man’s land. At Amboli, there was a road nearby, and buses used to ply from Sawantwadi to Belgaum, so people had heard about the radio. The Portuguese soon found out and sent somebody to make inquiries, and they were working through the local smugglers to find us. So we shifted to a more secure site,” said Libia. The team moved to Castlerock hill, closer to Karnataka.

The Portuguese did their best to thwart their efforts by jamming their frequency, but this problem was easily tackled by tweaking the frequency. By December 2, India had readied India’s first tri-service assault, called Operation Vijay, to liberate Goa. On December 11, troops from the Indian Army amassed at Belgaum, preparing for the ground assault. On December 16, Libia and Vaman were driven in a military jeep to Belgaum, where they were asked to set up their transmitter in a guest house.

On December 17, the couple broadcast a direct message from India’s defence minister addressed to the Portuguese governor general, asking him to surrender. The message was transmitted every hour, and to the airport tower at Dabolim. As no reply came, Operation Vijay was given the go-ahead.

While naval warships pummeled the Portuguese fortifications and the Indian Air Force bombed key installations, Indian Army troops launched a ground assault from the north and eastern flank. Completely outnumbered and outgunned, Portuguese governor general Manuel Antonio Vassalo e Silva gave up, and the war was over in 36 hours.

On the evening of December 18, when Libia met Chief of Army Staff General J M Chaudhary, he said, “Now, Kumari Lobo, what next? What do you want to do?”

On an impulse, the couple said that they wanted to declare that Goa was free from sky high. The Indian forces liked the idea. So on December 19, Libia and Vaman were put on an Indian Air Force liberator to fly over Panaji.

“Rejoice, brothers and sisters, rejoice. Today, after 451 years of an alien rule, Goa is free and united with the motherland”, was the message announced in Konkani and Portuguese from Goa’s free skies.

The declaration was made to synchronise with the ceremony below at the Palacio Idalcao (now Adil Shah palace), where the Portuguese flag was lowered and the Indian tricolour went up for the first time on Goan soil.

Post-Liberation, Libia was tasked with going through Portuguese documents and it was here that she came across Portuguese army commandant, major Filipe de Barros Rodrigues’s report about the Voice of Freedom.

The report states that the ‘Voice of Freedom’ had “assumed the command of the entire propaganda and has maintained its aggressiveness and militancy”.

It also said that the station "threatens, criticises, persuades, explains, changes colours, alters perspectives, but in everything it says, it carries a sharp stiletto", and was “the only voice which was hurting us (Portuguese) at close range”.

1961: December, 1-19

From: Paul Fernandes, Dec 19, 2021: The Times of India

Paul Fernandes, Dec 19, 2021: The Times of India

PANAJI: Goa’s six-decade-long journey following Liberation is chock-a-block with stark changes and a gamut of events that straddle a wide spectrum.

While the tiny territory has undoubtedly achieved considerable progress with its health and other parameters being high across India, it has also irretrievably lost a lot along the way, as some citizens say.

Life was quiet and peaceful — good in many ways and difficult in others — before Liberation.

“An anna (four paise then because a rupee had 64 paise instead of the 100 later) could buy several food items. Inflation was unheard of and for two annas and half (ten paise), one could have pao, bhaji and tea,” says 78-year-old Panaji resident, Milind Angle. Though the suppression of foreign rulers hurt and impeded the type of progress people craved for, certain benchmarks they set appealed to sections. “Life was peaceful, and there was honesty everywhere. The Portuguese had an image of honesty and patience, rules were tough and strictly followed,” Angle says.

Uday Bhembre, a former legislator and Konkani writer, agrees that the crime graph was low as the fear of the law prevailed in the police state. “The military was present everywhere. Windows didn’t have grills and people in villages felt safe and slept with their doors open or ajar,” he says.

The newfound freedom drew back even Goans living abroad.

Dr Alfredo de Costa, a physician who studied in Lisbon and interned in the Angolan military under Portuguese rule, chose to return home a few months after Liberation. “People’s happiness quotient was high then as their aspirations were simple. Everybody took an afternoon siesta, but what is the use now of having pots of money,” de Costa says.

The Portuguese relied on imports to cope with food and other requirements, but poor economic conditions constrained people’s purchasing power.

“The British at least set up industries, but the Portuguese made the people dependent on imports,” Bhembre says.

The educational sector functioned in an almost vacuum. Goa had only a few high schools, just before Liberation, besides Lyceum in Panaji and Goa Medical College. For higher education and jobs, locals migrated to other states and abroad.

“The end of colonial rule brought hope and people had great expectations from democracy as we were guaranteed rights of our own to chart out a new life,” Bhembre says. But the ground reality was less harsh during transitional years than in recent decades.

“Though we got democracy and became part of the republic with constitutionally guaranteed rights, we have not yet or so far, been able to tap all these instruments — of development of persons and properties — properly and wisely. Our lands and businesses are being taken up by others, we are becoming aliens in our own land and the difficulties we face are increasing every day and not getting solved. The ultimate objective is that our life should be easy and happy,” Bhembre says.

Goa’s elected government created a town and country planning (TCP) department in 1963, though the TCP Act for Union territories of Goa, Daman and Diu was operationalised only in 1975.

“TCP in 1963 had federal seed funds and technical support through a model law for regional, settlement and local spatial plans with simplified development control rules under the Bandodkar government. Through the TCP Act, Regional Plan 2001 offered directional growth to the single district state as created in 1987,” former chief town planner Edgar Ribeiro says.

For Goa, with limited land and other resources, planning years ahead to decide land use interlinked with services, the scale of intensity and identifying development control regulations in a participative manner has been a problem, though planning has been decentralised for a down to top approach through the 73rd and 74th amendments to the Constitution. “A plan is the basis of good governance and in the interest of transparency. However, corruption thrives on vagueness and the RP 2021 has been undermined by many devious unconstitutional amendments, especially 16 (b) of the TCP Act. Many of our politicians are too stunted and cannot think beyond increasing FAR and conversion of land as a means of governance,” architect and general secretary of Goa Bachao Abhiyan (GBA), Reboni Saha says.

Disastrous impacts of climate change raise immediate concern for course correction and remedial action for Goa. “For this, the government needs to revise the state’s climate policy to include the natural and built-up heritage and to device policies that limit the carbon footprint induced development,” conservation architect and former national coordinator, risk preparedness of heritage sites, ICOMOS-India, a Unesco advisory body, Poonam Verma Mascarenhas says.

Concurring with her, Ribeiro says updating of the regional plan is required to protect Goa’s much-admired fragile ecosystem and called for serious governmental introspection. “It is sorely needed when population growth is manageable, but land ownerships are changing hands at an alarming rate,” he says.

The restoration and revival of all khazan and comunidade systems are important for growing food and protecting ecological degradation.

“Every department linked to planning and development must work together. Land, rivers, cultural heritage, forests are all resources and not commodities, signifying man’s symbiotic relationship with nature and cornerstone of Goan identity, which can be guiding forces if the next generation is to be given a chance to thrive,” she says.

INS Trishul

See graphic:

Goa: The events of 1-19 December, 1961