Gond: Deccan

Contents |

Gond

This article is an extract from THE CASTES AND TRIBES OF H. E. H. THE NIZAM'S DOMINIONS BY SYED SIRAJ UL HASSAN Of Merton College, Oxford, Trinity College, Dublin, and Middle Temple, London. One of the Judges of H. E. H. the Nizam's High Court of Judicature : Lately Director of Public Instruction. BOMBAY THE TlMES PRESS 1920 Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees |

Gond — a non-Aryan tribe, whose featu'res, complexion and traces of totemism in their sections mark them as being of Dravidian descent. They inhabit the wild and mountainous tract of the Adilabad District which, flowing in a line parallel to the Paina Q'anga river, turns abruptly northward and, running between the Kinwat and Adilabad Talukas, sweeps into the Wun District of Berar. This region, which once formed a portion of the territory known as Gondawana, consists of a succession of hill ranges covered with dense forests of salai (BosWellia thmijera), sag or teak (Tedona grandis), mahua (Bassia latifoUa) and other wild trees. Occasionally, in a mountain gorge, or on a hill side in an open spot, a Gond village stands surrounded by patches of cultivated land. The village consists almost entirely of huts of wattled bamboos.

Character

Owing to their secluded jungle life, the Gonds are a very shy, timid and retiring race. Towards strangers they first assume an attitude of reserve and suspicion, but once they get over their shyness, they become very hospitable and communicative, ll is generally reported, by those well acquainted with their habits, that where the Gonds have not come under the influence of the inhabi- tants of the plains, they bear a high character for honesty and truth- fulness. The men are, however, strongly addicted to drink, are very indolent and show a great dislike to methodical work. In a Gond village, one is struck at the sight of the males sitting idle, with no interest in work, while the females are toiling hard from morning till night at all kinds of indoor and outdoor work.

Physical Characteristics

The predominating physical charac- teristics of the tribe are, a short flat nose with spreading nostrils, black and sparkling eyes, thick and projecting lower lips, generally scanty beards and moustaches and complexions varying from jet black to dark brown. Of a strongly built, muscular frame, capable of great endurance, the male averages 5 ft. 4 in. in height ; both sexes possess an erect carriage and a peculiar gait of long and fast strides.

Dress and Ornaments

The Gonds are scantily dressed. A strip of cloth, neeirly a yard long, passed between the legs and fastened, before and behind, to a string around the waist, and a rag tied round the head, make up the complete dress of the male. The dress of a woman consists of one long piece of white, or coloured cloth, girt round the loins, the lower half of which hangs to the knees, the ends being passed between the legs and fastened behind, while the upper half is carried across the breast and over the left shoulder which, however, barely covers the breast. The women wear no bodice or petticoat. Their coarse black hair is collected behind in a knot, sometimes artificially enlarged and decked with wild flowers. Tattooing is very fashionable and their chest, arms and back are covered with most fantastic designs. A mass of very small black and white beads and mock corals, worked to form a necklace, adorn their necks and large brass ear-rings are worn in their distended ear-lobes. On their wrists they wear huge bracelets of pewter or bell-metal.

Origin

The origin of the Gonds is obscure and their tradi- tions throw no light upon their tribal affinities. " The name Gond or Gund," says Mr. Hislop, " seems to be a form of Kond or Kund. Both forms are most probably connected with the Telugu equivalent for a mountain, and therefore signify Konda Wanlu, or hill people. This name they must have borne for many ages, for we find them mentioned by Ptolemy, the geographer (A.D. 150), under the name of Gondaloi." A popular legend traces the origin of the tribe to the Pandav prince Bhimsen and the demon damsel Hedumba of Mahabharat fame. It is said that Hedumba gave birth to five sons simultaneously, £md was so disgusted at this unnatural event that she deserted the infants to their fate. In their helpless condi- tion, they were found by Mahadev, who took compassion on them and consigned them to the care of Parvati. She took charge of the infants, but nourished them at her left breast only. Even the divine nursing could not subdue their inborn tendencies towards cannibalism. for these monstrous infants begcin to imbibe, along with the milk, the very life blood of Parvati's body which, in consequence, wasted day by day. Mahadev, alarmed at her emaciation, divined its cause and confined the wretches in a mountain cave. From this they were rescued by Pedlingu, a renowned sage, who, henceforth, became their preceptor, related to them their past history and initiated them into the worship of their forefathers. The four elder brothers became the founders of the four important sections of ^e tribe : (1) Satdeva (worshipping 7 minor deities, i.e., 5 Pandavas, Kunti and Draupadi) ; (2) Sahadeo (worshipping 6 minor deities, i.e., 5 Pandavas and their wife Draupadi) ; (3) Pachdeo (worshipping 5 minor dejfies, i.e., 5 Pandavas) ; (4) Chardeo (worshipping 4 Pandavas, the youngest being dropped). The youngest of the brothers was appointed, under the name of Pardhan or Pathadi, the family bard and genealo- gist to his elder brothers, on whose charity he was ordained to subsist. This legend, so absurd in its conception, goes to illustrate how myths are devised by aboriginal tribes to glorify their origin, while in process of transition into the Hindu castes.

The Gonds of Adilabad are divided into six sub-tribes : (1) Raj Gond or Gond, (2) Pardhan, (3) Thoti, (4) Dadve, (5) Gowari, (6) Kolam, which are all endogamous. The terms Raj Gond and Gond, formerly used to distinguish the ruling classes from the bulk of the people, have now become synonymous, the poorest Gond calling himself a Raj Gond. This change was probably brought about after the Raj Gonds had ceased to be a ruling power and had sunk into political insignificance. A tendency is still observed among the upper classes of the sub-tribe, to hold themselves socially aloof from the masses, and a sort of hypergamy has sprung up between the two, the former accepting the daughters of the latter in marriage, but showing reluctance to give their own in return. Some of the Raj Gond famil- ies, which belonged to the Gond Rajas, have, by reason of their long contact with the more civilized communities of the plains, so far advanced towards Hinduism that they actually lay claims to a Rajput descent. They profess to follow the Hindu religion, rele- gatmg their ancient tribal customs to their women, employ Brahmans for religious and ceremonial purposes, practise infant marriage and prohibit widow-marriage and divorce. These facts clearly indicate that disintegrating forces are at work, tending to split up the sub-tribe into two endogamous groups, one of which may, in course of time, become entirely a Hindu caste. Regarding the origin of the Raj Gonds, Mr. C. Scanlan (" Indian Antiquities," Vol. I, page 54) remarks: "Concerning their origin, it is said that while a Rajput prince was once out hunting he espied a goddess perched on a rock enjoying the wild scenery of the country. They became enamoured of each other and were blessed with a son, who was the ancestor of the Gonds, and since he claimed his origin from a goddess and a Rajput, tLey style themselves Raj Gonds and Gond Thakurs."

The Pardhans or Pathadis are the helots of the Gonds, and serve as genealogists and bards to the Raj Gonds, singing the exploits and great deeds of their rajas and heroes to the music of a kind of violin called hp^gri. This musical instrument is regarded, amongst them, as a mark of distinction which each Pardhan is bound to possess, or have tattooed on his left fore-arm. No marriage of a Raj Gond is celebrated, nor are his death rites performed, unless a Pardhan is present to receive the marriage presents, or to claim the raiments of the dead.

The Thotis, the bards of Pardhan, form a group of wandering minstrels. Their male members are mainly engaged in making small bamboo articles and in selling medicinal herbs, while the females are skilful tattooers. These three sub-tribes, resembling one another in every respect, appear to have once formed a single group, subse- quently broken up on account of internal disorganisation, the Pardhans being an offshoot of the Raj Gonds and the Thotis that of the Pardhans. The Dadve formerly recruited the armies of the Gond Rajas, but now they work as day labourers. The Gowaris tend milch cattle and for this reason dwell in villages outlying the hill tracts. Their long association with the neighbouring Hindus, has so far affected their character and customs, that they are often found merged into the lower castes of Hindus and cut off from their own tribe.

Very dark of skin and short of stature, possessing habits of the most primitive character, the Kolam presents a fair specimen of the pure Dravidian type. He constructs his tiny bamboo cottage on the crest of the highest hill, and so migratory is he that on the least alarm he shifts his quarters to the most inaccessible part of a mountain. He is very ugly in features and filthy in habits, never bathing for days together. He speaks a dialect called Kolami, vifhich differs con- siderably from the other Gond dialects. In customs and usages, the Kolams resemble the Raj Goods, to whose Rajas they pay homage and submit their internal quarrels for decision. All these facts taken together help to the conclusion, that thes6 sub-tribes are essen- tially the branches of a formerly compact tribe, of which the Raj Gonds represent the original nucleus. This view derives support from the fact that each of the sub-tribes is divided intjt' the same exogamous septs.

Internal Structure

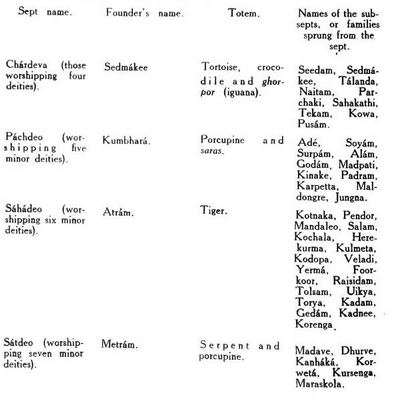

The following table gives the exogamous sections of the tribe, with the founder's name, totem and sub-septs, or families, which each sept comprises : —

All the septs are clearly totemistic, although they do not bear the names of the totems associated with them. The totem is taboo to the members of the sept to which it belongs, e.g., a Seedam holds the tortoise in the highest reverence and will neither eat, kill, injure or even touch it. It is really noteworthy that while the totems and the founders' names have been preserved, the totemistic neunes of the septs have been dropped, and replaced by fabulous titles. This indicates an attempt, pn the part of the Hinduised Gonds, to convert totemistic titles into eponymous ones and thus give colour to their pretensions for a mythical origin of an orthodox type. The sept name goep by the male side. The rule of exogamy is strictly followed. Thus a man cannot marry a woman of his own sept. No other sept is, however, a bar to marriage, provided that he does not marry his aunt, his first cousin, or his niece.

Marriage

The Gonds marry their daughters both before and after the age of puberty. The former is, however, preferred by the more respectable members of the tribe.

Polygamy prevails and, in theory, there is no limit to the number of wives a man may marry. Sexual indiscretions, before marriage, are indulgently treated. If a girl becomes pregnant before marriage, she is called upon to disclose the name of her lover, and he is forced to accept the girl as his wife • On the other hand, sexual indiscretion with an outsider involves instant expulsion from the tribe. Two forms of marriage are recognised by the Gonds.

(I) The more polite or regular form necessitates the consent of the parents of both parties. The father, or gujurdian, of the bride- groom takes the initiative and, when a girl is selected by him, he proceeds, formally, to the house of her parents to make the proposal of marriage on behalf of his son or ward. In the preliminary nego- tiations the question of the bride-price (varying from Rs. 9 to Rs. 20) takes a prominent part. Every thing having been ananged to the satisfaction of both parties, all the male members repair to a liquor shop and solemnize the betrothal with a drink, at the expense of the bridegroom's father. A singular custom requires every man before drinking the liquor to cry out " Ram Ram," an omission of which involves social disgrace. The caste people are then entertained at a feast. On this occasion, the bridegroom's father contributes a cock and the bride's father a hen ; the boy's father places a pewter bracelet on the girl's wrist and this completes the ceremony of betrothal. On the day previous to the wedding, the bride's family escort her to the bridegroom's village where, on arrival, they are established under a shady tree and are met, towards evening, by the party of the bridegroom. As a mark of greeting, gruel and onions are exchanged by both parties. The whole company then goes in procession to the bridegroom's house. The bride and bridegroom are next alternately smeared three times with a paste of oil and turmeric, and bathed in warm water. The rest of the night is spent in feasting, music, singing and dancing. Early next morning, in the courtjard of the house, a canopy of mahua (Bassia latijolia) and salai {BosWellia thurijera) leaves is erected and, underneath it, five earthen jars of water, crowned with lighted lamps, are arranged in the form of a quincunx on a square drawn of jawari flour.

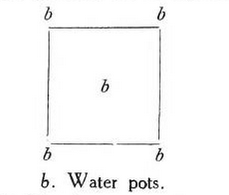

The following plan illustrates the arrangement : —

An earthen vessel full of water, and covered with a concave lid, is placed on the cowdung hill of the house, in the open air, and after being solemnly worshipped is left guarded by two girls. This ceremony over, the bridegroom, dressed in cotton clothes dyed yellow with turmeric, armed with a spear and accompanied by music, which IS most discordant, is led by his relatives and friends to the cowdung hill, one of the females bearing, on her head, a sacred lamp. The bride, similarly attired and attended, joins him and the bridal pair stand opposite each other near the consecrated earthen pot, the bride- groom facing east and the bride west. A curtain is held between them, and the bridegroom places his right foot upon a wooden stool, placed beneath the curtain, the bride simultaneously touching it with her' own. Then follows the essentia! portion of the ceremony, when the bridegroom, with his right foot resting on that of the bride, puts an iron ring on the little finger of her right hand. The screen is withdrawn and the wedding procession returns to the booth, where the bridal pair are bathed with water taken from the sacred earthen pots previously deposited. After changing their wedding clothes, the happy couple walk five times round the pots, the sacred lamp burn- ing all the while. They afterwards sit side by side on the floor, with their faces turned towards the east. Grains of rice are then showered upon their heads by the assembled guests. The bride- price is then paid and a present of clothes made to the girl's parents. A feast to the caste, at the expense of the bridegroom's parents, com- pletes the marriage ceremony. The bride's father, on his departure, is decorated with a garland of twenty-five cowdung cakes with a sheep's leg pendant in the centre.

The second form, representing marriage by capture, is resorted to by those Gonds, who are too poor to pay the bride-price, or to bear the subsequent expenses. This custom is in full force emiong the Goilds of the hilly districts, though it is dying out in the plains owing to the rigours of the law. A girl having been selected, and all information regarding her daily movements having been gathered, the friends of the boy proceed to her village, and lie m concealment close to the place she is expected to visit. In the meanwhile, an elder relative of the bridegroom, generally his father or brother, goes into the village, and wins the assent of the headman to the match on payment of Rs. 2. He then joins his comrades. On the girl making her appearance, sometimes alone, but often in company with others, he falls upon her all of a sudden and touches her hand. This effected, the marriage contract becomes irrevocable, even if the girl escapes from his hands. Great resistance to this capture is often offered by the women present, and the man is chastised in right earnest. Stones and other missiles close at hand are freely hurled, and the man is often severely injured ; but the custom allows the women to accept a bribe, for more polite reception, and in such cases the girl is borne away in tears to the boy's house and there married in the absence of her parents.

Widow-Marriage

A widow is required to marry' her late husband's younger brother, if alive, but, on his refusal, if her choice falls upon an outsider, no restriction is imposed upon her. In the latter case, however, she forfeits all claims to the custody of the children by her late husband. Infants at the breast are allowed to remain with their mothers, on the express condition that they will be restored to their father's family on their attaining a marriageable age. The ritual followed on a widow's re-marriage is of a simple character. Late in the evening, the woman goes to the house of her husband elect. In the court-yard a stool is placed, on which the bridegroom takes his seat. The bride bedaubs his body vvith oil and turmeric, and bathes him with warm water, and with tHe remaining water she bathes herself. Both of them wear white clothes and enter the inner court-yard, where the bride seats herself on a wooden stool, and the bridegroom ties a string of black beads round her neck and smears red lead powder on her forehead. The proceedings terminate with a feast.

Divorce

Divorce is very common amongst the Gonds, in which both husbands and wives freely indulge. Elopements are of daily occurrence. A woman taking a fancy to a man, simply runs away with him, and if the aggrieved husband is a rich man, he imme- diately marries another wife, and there the matter ends. But should the husband be <. poor man, he merely claims the bride-price paid for her. as a virgin, from the paramour of the unfaithful wife, and with the amount thus obtained he is at liberty to marry another woman. Divorced women are allowed to marry again by the same ritual as widows.

Religion

The religion of the Gonds is animism, which flourishes, in its pristine vigour, among the inhabitants of the hilly tracts, although it is gradually losing ground among those of the plains. The principal deity of the Raj Gonds, Pardhans and Thotis is Phersaphen (great god), who is acknowledged to be the supreme god of the universe, and is worshipped with great veneration and awe, under the names of Zonkari, Jalgidar, &c. The emblems of the god vary with the locality of the worshipper, but generally consist of small iron pieces, resembling arrow-heads, each a span in length. corresponding in number to the minor gods of the worshipper, which, enclosed in an earthen pot, with its mouth closed by a bamboo basket, are hung on a mahu€i tree (Bassia latijoUa) at some distance from the village. The priest, called hptddd is a Raj Gond, who officiates at sacrifices to the god and keeps guard over the sacred pot. No woman or stranger is allowed to cast a glance upon the tree bearing the sacred pot, or to go anywhere near it.

Phersapen is worshipped once a year with great pomp and ceremony. It is generally on an evening in the month of Chait (March-April) that a sacrifice of goats and fowls is offered to the god, at the foot i»f the sacred tree, after which the emblems are taken down by the priest, who is clothed in red, and mounted on a bamboo pole. They are then carried in procession, headed by the Pardhans, with music, to some big river or tank where they are solemnly washed. Close to the village, a canopy is erected for the occasion, under which a branch of the salai tree (BosWellia thurijera) is planted, and it is here that the bamboo pole, bearing the sacred arrow-heads, is deposited. . Frankincense is burnt before these emblems and cows, goats, and fowls are freely sacrificed by the officiating priest, on behalf of the community as a whole, and of individual members in pursuance of vows taken in times of trouble. Formerly, human sacrifices were offered on this occasion, but the rigours of law have now put an end to this. The flesh of the slaughtered animals is then cooked and the rest of the night is spent in feasting, dancing and revelry. The ceremonies are conducted with great secrecy and no Hindu, or Gond woman is allowed to be present. Towards the dawn of the following day, the emblems are taken back to the tree, and restored to their accustomed place.

Next in rank is Bhimsen, or Bhivsen, the favourite and charac- teristic deity of the Kolam and Dadve Gonds, represented by an oblong piece of mahm wood, 4 ft. in length, and daubed with sesame oil. With one end fixed in the ground and the other covered with peacock feathers, the god is set up upright, in a bamboo hut outside the village. He is propitiated twice a year, in the month of Vaishakha (April-May) and on Til Sankrdnf (when the sun enters Capricorn), with offerings of goats, fowls and cows, which afterwards furnish a feast for the assembled votaries. A Kolam priest presides • on this occasion ; to the sound of a drum and cymbals and to the jingling of little bells worn in a belt round the waist, he dances and sings alternately, in honour of the deity. Every three years, the symbol of the god is carried to the Godavari river for ablution.

The worship of Bhimsen, formerly confined to the Gonds alone, is fast spreading, and Hindus of all orders now hold this animistic deity in reverence. A legend is already current identifying this god with the Pandav prince Bhimsen and giving him a seat in the Hindu pantheon. This furnishes a good example of the unconscious recep- tion of animistic deities into the ranks of the Hindu gods.

The Gowaris reverence Kanhoba, an incarnation* of Vishnu, in whose honour they observe a fast on Jamndshtami, the 8th of the dark half of Shravan (July-August). In addition to the principal deities mentioned above, a host of evil spirits and minor gods are appeased by the Gonds. The former include the goddesses of cholera, smallpox, fever, &c., and other malevolent spirits, all of which must be conciliated in one form or another, in order to avert calamities proceeding from them. Among the latter are :* (1) Jangu Rai Tad, a blood-thirsty goddess dwelling in a dark and dreary cave, near the village of Sakada in the Jangaon Taluka. The goddess is said to have been wedded to Bhimsen in an adjoining cave and, if duly propitiated, is credited with bringing good luck to her devotees. She once insisted on demanding human lives as the only sacrifice acceptable to her ; but, since the establishment of a vigilant police, and the strong rule of law, she is quite content with the blood of kine and goats. The terrific form of Bhimsen is represented by a fire burning constantly in a cave on the Dantapalli hill. The god is generally invoked by offerings of animals, before the commencement of agricultural operations, at the sowing season, and before the harvest is gathered in. It is also worshipped should the rains fail and a drought continue. Bhimanna is also worshipped at Gololi, m the form of a shaft fixed in the ground. It is rather curious that the priests of these two cults never meet. Serpent worship prevails and, in the month of Magh (February-March), a big fair is held in lionour of the serpent god at Kesalapur, when a huge sacrifice if offered at 'the altar. Thousands of goats and fowls are slaughtered on that day, and the blood-thirsty god is not satisfied until the altar is completely filled with blood. The votaries believe that not a drop of blood remains about the altar the following morning.

The Gonds have a strong belief in witchcraft. Witches are supposed to hold communion with the dark spirits ; they meet them in the forest at night and dance and sing with them in a nude condition. Brahmans are not employed by the Gonds, either for religious or ceremonial purposes.

Disposal of the Dead

After death, the bodies of persons who are married are burnt, and the unmarried, or those dying of small- pox or cholera, are buried. On the death of a Gond, his relatives and friends assemble at his house, where the body is carefully washed and, dressed in a white cloth, is placed on a bamboo bier and borne by four men, not changing hands, to the cremation ground. The chief mourner heads the procession, bearing in one hand a sling, with a triangular bamboo bottom, in which is placed an earthen pot filled with burning cowdung cakes, and in the other an axe with the head reversed on the handle. The corpse is laid on the funeral pyre, which is kindled with the cowdung cakes. When the pyre is well alight the chief mourner performs an ablution, and filling the earthen vessel with water walks with it three times round the pile. When the fire has nearly burnt down, he throws the axe three times over the pyre and, taking it with him, goes to a river or tank, followed by the bier bearers and other relatives. Having bathed, they adjourn to a liquor shop, rub the mahua refuse with the big toe of the right foot, and apply the soot of the furnace to their forehead with the little finger of the right hand. The liquor seller sprinkles them with country spirit, after which they sit down and drink. This over, they leave the axe with the liquor seller and return to the house of the deceased. On arrival, they are received at the door by a female relative of the deceased and sprinkled over with water from an earthen pot, into which a burning coal has been previously thrown. Next morning, all the relatives, male and female, holding mango twigs, visit the burning ground. A cow is sacrificed on the spot where the corpse was burnt, and the spirit of the dead is invoked to accept the offering and be satisfied. Each person present makes five turns round the pyre, collecting the scattered ashes with the mango the fig. As on the preceding day, the mourners bathe, drink, and return home. On the afternoon of the third day, the male members of the family repair to a grove of mahua trees adjoining the village. A square foot of ground is plastered with cowdung and before it are arranged small heaps of uncooked rice, as many in number as the minor gods of the deceased. A fowl (a cock or hen according to the sex of the dead) is decapitated and the spot covered with its blood ; the head is left before the heaps of rice and the body is cooked and eaten by the assembled relatives. The Uquor shop is again resorted to for the purpose of taking back the axe formerly left there. This terminates the funeral rites. No periodical cere- mony is performed for the propitiation of departed souls, but dead relatives are held in great reverence. Burial is resorted to in cases of poverty. Tombs are erected over the remains of the rich, and those that are esteemed, to perpetuate their memory. Magnificent tombs of the Bond Rajas may be seen at Manikgad, neqr Rajura, and also in the vicinity of Jangaon.

Social Status

The social status of the Gonds cannot be clearly defined. With the exception of a few families, who have been admitted to a high rank in the Hindu social system, by reason of their abstaining from beef and employing Brahmans, they stand wholly outside the Hindu caste system. No orthodox Hindu will ever eat their food, or accept water from their hands. In matters of diet they are not very particular. They partake of beef, pork, fowls, fish, field rats, snakes, lizards and buffaloes — in fact all animal food. They have no repugnance to eating the flesh of animals which have died a natural death ; but they will refuse to eat the leavings of Hindus, even of Brahmans. Although wholly outside the pale of Hinduism, they are not free from caste prejudices and, amongst themselves, have formed various social grades, imitating the Hindu castes, as regards restrictions on diet and matrimonial alliances. As has already been mentioned, the Raj Gonds occupy the highest position, and the Pardhans and Thotis, whose touch is regarded as unclean and unceremonial, the lowest.

Occupation

The original occupation of the Gonds is believed to be hunting and agriculture, which latter is carried on by the method known as dhya or daha. In this primitive mode of tillage, neither plough nor hoe is used, but the men cut trees, burn them, and sow seed by small handfuls in narrow holes made in the ashes. As the earth gives proofs of exhaustion, generally in two or three years, the Gonds move off, bag and baggage, to some fresh patch of land and resume their .operations. The crops they raise are jawari, rice, chillies, maize and various pulses. Cotton is also occasionally grown. The largest share of the field labour devolves upon the women, whj> assist the men in sowing, weeding and gathering in the harvest.

The scanty produce of their fields hardly suffices for their maintenance and they consequently have to eke it out by consuming mahua flowers, wild roots and fruit and a variety of jungle herbs. Every household has a sort of rude oil-press, in which oil is extracted from mahua seeds and used for eating and lighting purposes. The Gonds have their own carpenters, who make rude wooden imple- ments, and their own distillers, who manufacture liquor from mahua flowers.

The Gonds have, hitherto, been lords of the woodlands, roving at will and enjoying perfect freedom in selecting land for cultivation and making new clearances. But the situation has now changed. The forest conservancy laws, which have come into force of late, and the extension of metalled roads, which have opened up their secluded tracts to foreign settlers, are interfering seriously with their dh^a method of cultivation. The Gonds cire thus being com- pelled to take to settled cultivation with the plough, and to exchange their free life for the restraints of an ordered existence. This new life is proving uncongenial to them, for it has created new wants, which their scanty resources cannot meet, and the result is that these simple jungle people are gradually being drawn more and more within the clutches of the wily money-lenders of the plains and are being subjected to all the evils of indebtedness.

A few of the Gonds, especially the wild Kolams, have been forced by later immigrants into the heart of the hilly forests, where they still maintain their straightforward independence and manllneia.

These earn their living by hunting, making strong and durable bamboo mats and baskets, and collecting honey, charoli, mahua flowers, bees' wax, resins, gums and other jungle products, which they barter to a hania, in exchange for food-grains and other neces- saries of life.

Early History Of the early history of the Gonds very little is known. They established governments, one of which ruled the country which once comprehended a portion of the Adilabad District of H. H. the Nizam's Dominion, and the present Chanda District of the Central Provinces. It was founded by Bhim Ballal (804 A. D.) and had capitals at Jangaon MowjUa, and at Manikgada on the Wardha. Khandakya Ballal, the 10th Raja, transferred the seat of government to Chandrapur or Chanda, which he founded on the Zarpal river in 1261 A. D. The legend is, that Khandakya Ballal was suffering grievously from leprosy, of which he was completely cured by bathing in the balmy waters of the river ; this induced him to select the site, as a lucky place, for his capital.

The town was walled by Hirabai, the 12th ruler, who also built the shrine of Mahakali and laid the foundation of the Chanda fort. At a later date the kingdom became subject to the Bhoslas of Nagpur. in 1743, the Gonds raised an insuuection, which Raghoji Bhosla quelled, annexing the principality to his dominions.

Another Gond principality established its capital at Atnur, about 40 miles west of Jangaon, where the splendid archi- tectural remains still bear witness to its former glory and magni- ficence. A Gond-Rajput dynasty, under the name of Kakatiyas, is said to have reigned at Warangal for more than 400 years. The kingdom became very powerful about the end of the 13th century, but, being involved in a conflict with the Muhammadans, its power continued to decline, till it was at last swept away, in 1424 A. D., by the generals of Ahmad Shah Wali, one of the Bahamani kings.

Connected with the Gonds of Adilabad, though not included among them, are the Koitor or Kois, who occupy the Warangal District, extending from Bhadrachalam, on the banks of the Godavari, down to the neighbourhood of Khamamet. A tradition prevails that famine and internal disputes drove them to this region from the high- lands of Bastar, on the eastern banks of the Godavari. Both the Gonds and the Kois have a physical resemblance and are, in their features, quite distinct from the people of villages ; but each of them has a different tongue, the Adilabad Gonds speaking almost the pure Gondi, while the Kois have a dialect with a great preponderance of Telugu words. The term Koitor or, in its radical form, Koi, has been supposed to be derived from \onda, the Telugu equivalent for mountain,' but it s'eems to approach more closely the Persian kph, meaning 'hill.'

The Koi men are dignified with the title of Doralu (lords) and the wSmen with that of Dora Sanulu (ladies).

The Kois divide themselves into five classes — Gutta Koi, Addilu, Perumbo Yadu, Koi Kammar Vandalu and Dollolu. The Gutta, or hill Kois, include the Madu Gutta, Pere Gutta, Vido Gutta, and other clans holding the highest rank among the tribe. The Koi Kammar Vandalu are Koi blacksmiths. The Dollolu are the reli- gious counsellors or bhdts (genealogists) of the upper classes and have charge of the Koi deities. Koi customs are not uniform, but vary with the localities, although, in their essential character, they are not distinct from those of the Gonds. Boys and girls generally marry when of fair age. Marriages, both by proposal and by force, are in vogue. A widow is sometimes carried off a day or two after the death of her husband, while she is still grieving on account of her loss.

Elopements are common and husbands are, occasionally, murdered for the sake of their wives. More disputes arise from wife stealing than from any other causes. The Kois pay devotion to Mamila, represented by a stump of wood, to whom human sacrifices are said to be still offered. It is customary to propitiate the goddess early in the year, so that the crops may not fail. The Kolam god Bhimsen is also worshipjjed. Korra Razu is the deity which presides over the tiger demon. Wild dogs are held in special reverence and even if they kill the cattle they are not injured. A festival is held when ifypa or mahua flowers (Bassia latijolia) are in blossom. When the new crop is ripe, and ready to be cut, the Kois take a fowl into the field, kill it, and sprinkle its blood on any ordinary stone put ud for the occasion, after which they are at liberty to partake of the new crop. The Kois have a strong belief in the spirit world,- and it is said that if they are not satisfied that the spirit of a departed person has joined the spirits of his predecessors, they waylay a stranger, kill him during the night, sprinkle his blood on the image of Mamila and bury the corpse before any one knows of the event. This horrid practice has been on the decline since 1842, when arrangements were made to prevent it.

In accordance with a very singular custom prevalent among them, the Koi women drive the men to hunt, on a certain day of the year, and do not allow them to return, unless they bring home some game. On this occasion, the women are said to be dressed in their husbands' clothes. Young persons and children are buried ; others are burnt. A cow or bullock is slain,* the tail is cut off and placed in the dead person's hands and the body burnt ; the friends and relatives then retire and proceed to feast on the animal. Three days later, the ashes are rolled up into small balls and deposited in a small hole about two feet deep. A child is named on the 7th day after birth. Having washed the child and placed it on a bed they put a leaf of the mahua tree in its hands and pronounce its name.

See also

Gond: Deccan