Government finances (the states): India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Revenues and borrowings

2013-18

From: Dec 3, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

2013-18: the revenues and borrowings of India’s state governments.

2021

From: Sidhartha, Sep 4, 2023: The Times of India

See graphic:

Off budget borrowings by Indian states in 2021

Off budget borrowings by Indian states

A 2021 study

Sidhartha, Sep 4, 2023: The Times of India

New Delhi : Just two states, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, had off-balance-sheet borrowings of around Rs 2.1 lakh crore in 2020-21, nearly half the extra budgetary resources utilised by the Centre, an analysis by a think tank has shown amid concerns that the states may be hiding the true extent of their borrowings by raising money through their public sector companies to meet subsidies and other liabilities.

A report on off-budget borrowings by the Centre for Social and Economic Progress has pointed to violations of the mandated debt level under the fiscal responsibility law. For instance, Andhra Pradesh maintained total liabilities at 35% of the gross state domestic product (GSDP) — but without factoring in the off-budget borrowings. Once that was added, in 2020-21, total liabilities added up to 44% of GSDP, the paper by Shurti Gupta and Jevin James estimated.

In the case of Telangana, the gap was nearly 10 percentage points — which meant that after factoring in the off-budget borrowings, the total liabilities shot up to 38.1%. In the case of Kerala, the gap was around three percentage points — 42.8% (including off-budget borrowings) against 39.9% — while it was a percentage point for Karnataka (22.4% versus 21.4%). The report indicated that the gap had widened since 2019-20, although the Centre has sought to crack down on it.

The paper estimated that 11 states between them had combined off-budget borrowings of over Rs 2.5 lakh crore, with data for Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Uttarakhand unavailable. The five southern states accounted for 93% of the off-budget borrowings with Telangana’s ratio at 10% of its GSDP.

It has suggested that the Centre’s extra budgetary resources (EBR) utilisation has dropped from over Rs 8 lakh crore at the end of 2019 (see graphic), but cautioned that the borrowings have been decreasing as the numbers may be incomplete. This is despite the Union finance ministry maintaining that the dues to the Food Corporation of India are now routed through the budget instead of the National Small Savings Fund or the NHAI programme being funded directly by the Centre instead of by issuing bonds, which did not reflect in the Union government’s Budget. So, what are states borrowing for? It is for a variety of reasons. In the case of Andhra, 35% was used by the state civil supplies corporation that manages the foodstuff value chain, much like FCI at the national level.

Tamil Nadu used 96% of the borrowings to meet the requirements of the state power transmission and generation company, with a similar trend seen for Punjab. Nearly 37% of Telangana’s off-budget borrowings were used up by Kalleshwaram Irrigation Projection Corporation.

Bank of Baroda’s study: details

Udit Misra, Sep 5, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Udit Misra, Sep 5, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Udit Misra, Sep 5, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Udit Misra, Sep 5, 2023: The Indian Express

How should state government finances be judged?

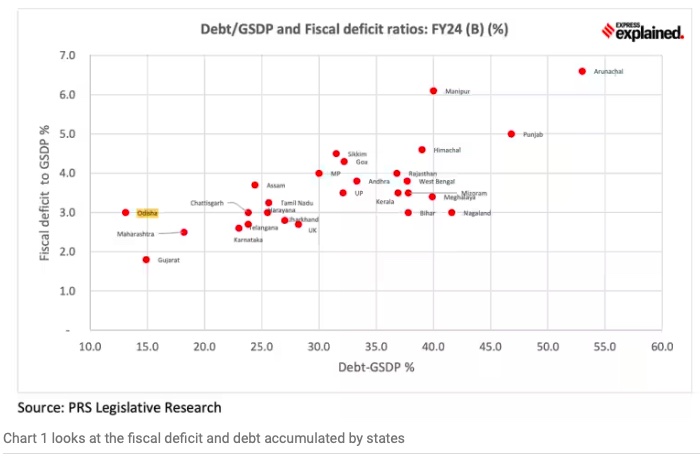

The economists at Bank of Baroda (BoB), a public sector bank, recently analysed the state of state finances based on the latest Budget data collected by PRS Legislative Research, a not-for-profit research organisation.

They analysed data for 27 states on four different counts:

Fiscal Deficit (which refers to the amount of money a state government has to borrow to meet its annual expenditure) expressed as a percentage of overall size of the state’s economy (the gross state domestic product or GSDP).

Debt (that is, the accumulated borrowings by the government over the years) expressed as a percentage of GSDP.

Outstanding guarantees that a state government provides; again expressed as a percentage of the GSDP.

Percentage of the total revenue income that a state government has to spend towards paying off the interest component of its debt.

Looking at these four criteria makes a lot of sense.

Fiscal Deficit tells us how much a state government has to borrow in the current financial year to meet the gap between its expenditures and revenues. Under the existing prudential norms, fiscal deficit should not exceed more than 3% of a state’s GDP.

Debt levels tell a longer-term story. If a state has been recklessly borrowing year after year, it would end up having a huge pile of debt. Under the existing prudential norms, debt should not go beyond 20% of a state’s GDP.

On debt levels, only three states — Odisha, Gujarat and Maharashtra — in India manage to meet the prudential norm. However, within the three, it is Odisha which has the lowest debt levels; this shows it has contained its annual fiscal deficit far better than the other two states over the recent past.

Barring these three, the situation just gets progressively worse. There are four states — Karnataka, Telangana, Assam and Chhattisgarh — which are at a debt level of less than 25%.

The next five — Tamil Nadu, Haryana, Jharkhand, Uttarakhand and Madhya Pradesh — have debt ratios between 25%-30%.

But as many as 15 states (out of the 27 for which data was available), had debt levels in excess of 30% of the state GDP (or GSDP). Four states, in particular, raise a red flag: Manipur, Nagaland, Punjab and Arunachal Pradesh.

On the fiscal deficit front, three states — Punjab, Manipur and Arunachal — have fiscal deficit of 5% and above. Taking into account the performance on both metrics together, Odisha comes out on top while Punjab lies at the bottom.

Odisha continues to do well in the third metric as well as shown by Chart 2.

However, it should be noted that the chart has information for just 21 states, and the outstanding guarantees (as a percentage of GSDP) are for the latest year available, which can be FY21, FY22 or FY23.

“This is another aspect of debt that has to be monitored because while the probability of invocation of guarantees is low, it pressurizes the states nonetheless and is not looked upon positively in the context of fiscal prudence,” states the BoB report.

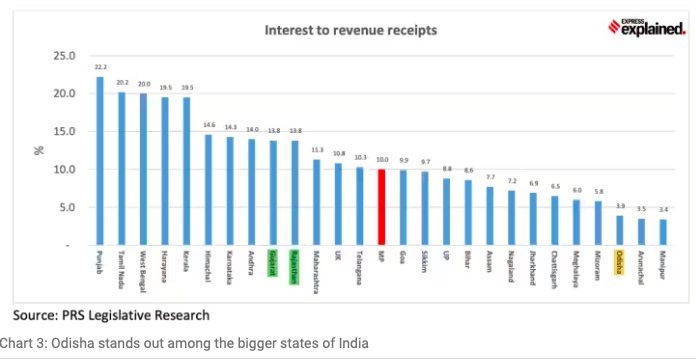

Lastly, Chart 3 maps the impact high debt.

“As debt increases so does the interest outgo, which in turn puts pressure on the revenue account as a larger part of the revenue receipts are used to pay interest which means that less is left for other purposes,” explains the BoB report. Here, again, Odisha stands out among the bigger states of India.

It is also noteworthy to look at how Gujarat and Rajasthan (both highlighted in green) are at the same level. In other words, even though Gujarat has much lower fiscal deficit, outstanding guarantees and overall debt ratios than Rajasthan, when it comes to the impact of high debt, Rajasthan is none the worse. That’s because Rajasthan’s revenues (the denominator in this ratio) has also grown proportionately, thus making it possible for it to afford the interest outgo.

Which are the best and worst-placed states?

In the final analysis, Odisha seems to lead the rest of India. “The debt to GDP ratio is the lowest and there are low contingent liabilities. The fiscal deficit too has been within the FRBM norms and the debt servicing ratio very low. This is a position of both comfort and strength,” concludes the BoB analysis.

Punjab, on the other hand, is the one big state that is pressurised on all counts — debt ratio, fiscal deficit, guarantees and debt servicing.

These results are similar to the findings of a report released by CARE Ratings at the start of 2023. It, too, pegged Odisha as the best and Punjab as the worst among the major states on fiscal parameters.

How does Odisha do it?

Madan Sabnavis, the Chief Economist of BoB, says that in Odisha’s case fiscal rectitude is more a case of astute expenditure management than revenue generation. That’s because states have limited scope of revenue generation. Sabnavis out lines three main reasons for Odisha’s continued success:

Sticking to annual fiscal deficit targets. Doing this ensures that Odisha doesn’t face higher interest rates and that keeps borrowing costs at a minimum.

Not compromising on expenditure. This means sticking to what is planned and not resorting to ad hoc changes mid-year. Having realistic budget estimates for both income and expenditure. Sabnavis says that often when a state government is struggling to meet the fiscal deficit target, it can resort to overstating its revenues and understating its likely spending. Presenting a realistic pictures helps Odisha government live within its means.

What may further help Odisha’s cause, as against a Punjab, is the fact that despite being one of larger producers of paddy, the state doesn’t run up a large subsidy bill (say on account of electricity or irrigation etc.) because it gets more rainfall than a Punjab, which has to produce a bulk of India’s wheat despite more erratic rainfall.