Gyanvapi mosque, Kashi Vishwanath temple

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

History

The Varanasi historian’s perspective

Chandrima Banerjee, July 11, 2022: The Times of India

What is the Varanasi historian’s perspective?

Singh breaks it down into three periods. First, the earliest archaeological evidence, which is a 4th-6th century CE seal that says “Avimukteshwar”, believed to be another name for Vishweshwar. A record by a traveller from Gujarat, either a merchant or a king, mentioned a temple built in the late 6th-early 7th century CE that could be it, Singh says. Then, Qutb-ud-din Aibak destroyed the temple that stood there in 1194 and Razia Sultana built a mosque in place of that temple in 1236. It was called Razia Masjid, he says, where temple pillars with Hindu lotus, Ganesha and mouse signs were preserved.

There’s a big gap in records after this, he says.

The next reference he finds to Varanasi’s religious spaces is when Alauddin Khilji and the Sultan of Jaunpur attack temples in the 13th and 15th centuries. “So where was the temple? If they are destroying temples from 1450 to 1520, there already was a temple [here],” he says. Finally, he adds, Mansingh was Akbar’s military commander and wanted parts of the Razia mosque to be used to build a temple. “With the patronage of Mansingh, who convinced Akbar, it started…The building was made in 1583-84 and opened to the public in 1585,” Singh says. “That temple remains and the pond. It is called wazukhana [now].” Aurangzeb destroyed this temple – “because through many generations, this was the Hindu root. He thought, ‘Let us finish that root’,” he concludes, with a swipe of his hand.

What the mosque’s custodian says

A distant rhythmic sound with mechanical precision punctuates our conversation. Abdul Batin Nomani is the mufti of Varanasi and Imam-o-Khatib (the one who leads the prayers) of the Gyanvapi mosque. When religious disputes within Islam arise in Varanasi, he resolves them. “Islam does not allow us to demolish a temple and take over the land to worship in a mosque,” he says. "There never was a temple on the plot where the mosque is."

“Even 50 years ago, Khanqa Rashidia library in Jaunpur used to have a handwritten book in Farsi called Ganj-e-Arshadi. It says, long before Akbar, the Sultan of Jaunpur built mosques in many places. This was one of them. During the reign of Akbar, this mosque was definitely in that place,” he says. “When Aurangzeb became king, he rebuilt the mosque on the foundation of a mosque that already stood. It was a mosque in place of a mosque…This temple demolition story came from the British. How else do you explain the 200-year gap between the supposed demolition and the first claims about the mosque being a temple?”

While leaving, I ask Nomani’s assistant, Gulzar, what the rhythmic sound in the background is. He takes me inside a house in the narrow bylanes of Pilikothi, the Muslim locality where the mufti lives, to show me — the Banarasi silks that Hindu weddings customarily can’t do without being woven by Muslim artisans.

After speaking with Nomani, I did try to trace the Ganj-e-Arshadi . While I could not find a translation, I came across a paraphrased version in English by renowned historian SH Askari. It does not refer to the section Nomani had mentioned but does mention Gyanvapi. This is what it said — the notes in brackets are mine:

His (that of Shaikh Yasin, a local Sufi saint and author) fanatical zeal, and not any general order of Aurangzeb, was mainly responsible for the sacrilegious destruction of some old temples near Vishweshwar and their conversion into a mosque which may or may not have been identical with Gyanvapi mosque. The compiler of Ganj-i-Arshadi refers to a letter of Miyan Shaikh Yasin, dated 15 Jamadi I, 1079 (October 1668), which briefly referred to such an action.

What follows is a long story which counters many aspects of the popular narrative.

A mason and seal engraver called Abdur Rasul was building a mosque near a temple in an area where Rajputs lived. The Hindus objected, convened a meeting and at midnight demolished the mosque’s walls and wounded Rasul. When Yasin came to know, he was furious. But Aurangzeb’s civil officials tried to keep the peace.

The civil officials were torn between a mixed feeling of sympathy and fear, and they sent a message to ‘Jihadi’ Shah (Yasin) not to take the law in his own hands and commit any sacrilegious action to the Dehra (temple) without the permission of the Emperor with whom the Raja of the locality had very good relations. But Shah Yasin, the religious zealot, paid no heed to the message sent by the administration.

Hindus stoned Yasin and his men from their balconies as he made his way towards what might have been Gyanvapi. Before soldiers could arrive,

Shah had already reached the door of the temple which was closed with heavy locks weighing 5 seers (about 6.25kg). Crying aloud Allah-o-Akbar they hurled themselves against the gate and it crashed. The door was thrown open, but there was another inner gate. It was also broken.

Some of Yasin’s men died, under attack from Rajputs and Sanyasis. But they managed to “ enter the temple, break the idol and ruin the Dehra .”

When this was done, a report was dispatched to Aurangzeb who, the note said, “felt relieved”.

What do Mughal records say?

Both munshi and diwan to Aurangzeb, Saqi Mustad Khan was the second chronicler of the emperor. Khan was asked to complete what another chronicler had started but was asked to drop, Alamgirnamah — either because Aurangzeb wanted to cut down on expenses or because he was foregoing fame for “things more esoteric”.

What Khan did complete is called the Maasir-i-Alamgiri. It covers 49 years of Aurangzeb’s reign and was compiled after he died.

Here, Khan recorded that on April 8, 1669, Aurangzeb found out that “ in the provinces of Tatta, Multan and especially at Benares, the Brahman misbelievers used to teach their false books in their established schools, and that admirers and students both Hindu and Muslim, used to come from great distances to these misguided men in order to acquire this vile learning. His Majesty, eager to establish Islam, issued orders to the governors of all the provinces to demolish the schools and temples of the infidels and with the utmost urgency down the teaching and the public practice of the religion of these misbelievers .”

Five months later, the chronicle says, on September 2 that year, Aurangzeb’s trusted general Mirza Mukarram Khan Safavi had died after having fever. “ It was reported that, according to the Emperor’s command, his officers had demolished the temple of Viswanath at Kashi .”

The narrative falls in line with the one in Ganj-e-Arshadi but the timeline does not — it is off by a year, which could be because of translation errors in either text. But what it does show is that the story of temples and mosques in Varanasi is not as starkly black-and-white as common narratives seem to suggest. History never is.

Nomani did say, however, that Aurangzeb had also done a lot to build and protect temples. For this, when I tried looking for primary evidence, I came across a 1653 farman issued by Aurangzeb, which lawyer-historian Rajani Ranjan Sen from Bengal had actually found and written about in 1911. An excerpt of the translation which follows a reproduction of the farman is this:

Our Royal Command is that after the arrival of our lustrous order you should direct that in future no personal shall in unlawful ways interfere or disturb the Brahmins and the other Hindus resident in those places, so that they may as before remain in their occupation and continue with peace of mind to offer up prayers for the continuance of our god-given empire that is destined to last to all time. Consider this an urgent matter .

(Illustrations: Sajeev Kumarapuram)

B

Chandrima Banerjee, July 12, 2022: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee, July 12, 2022: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee, July 12, 2022: The Times of India

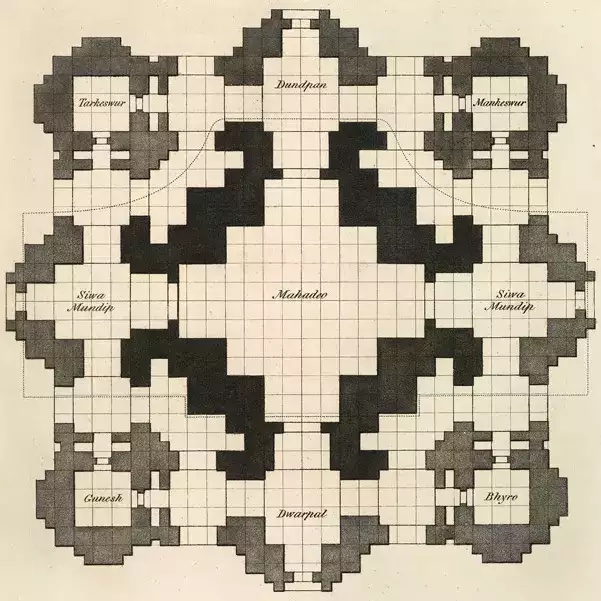

It is hard to imagine that 19th-century British administrator James Prinsep ever thought that the most dedicated inheritors of all he wrote would be Hindu orthodox groups in 2022. The petitions, the temple lawyers, local historians, the mosque survey report — all fall back on Prinsep’s book, Benares Illustrated, to buttress arguments claiming that the land where the Gyanvapi mosque stands actually belongs to the Vishwanath temple. These are the two images that came up with everyone I spoke to from the Hindu side of the case.

But what does Prinsep say about Gyanvapi? The temple’s image, he wrote, was from the southwest corner of the “Jama Masjid or principal mosque of the city. The dome and minaret surmounting the Hindu walls are the work of Aurangzeb, and the tombs are of the same date”. (Spellings have been simplified.)

The ground plan, architectural elevation and part of one of the “Hindu domes” remained as they were, Prinsep wrote, before adding a mix of history plus mythology again.

The lingam of the original temple of Vishweshwar was looked upon as the genuine type of Mahadeo or Shiva, which fell from heaven upon this spot, and was converted into stone. When the Musalmans set about their work of destruction, it is asserted, the indignant image leaped of its own accord into the Gyan Bapee hard by, where it still remains. The well has since been considered to be the centre of the Antargrihi Yatra, or the Holy Circuit, although a modern Shivala erected near the spot pretends to have reinstated the genuine lingam and fashion is rapidly acquiescing in the arrangement.

This is more or less what Rana PB Singh, a retired Banaras Hindu University professor, said and later, what the lawyers representing the temple in the legal cases would tell me. But while listening to Singh, I was thinking about the need to exalt the sources themselves for legitimising a narrative.

Singh’s name pops up in nearly all discussions on religion in Varanasi.

“Prinsep was a young chap. He was many things — archaeologist, numismatist. He made the first map of Benares in 1822. He was so influential that at only 28, he convinced Victoria to issue a coin with lotus petals, Lakshmi’s flower, on it,” Singh says. “The maps he made were 99% accurate. We don’t know how he did it.”

But colonial records are not always the most well-grounded archives. For instance, one of the first “grave” riots of Varanasi recorded in history is that of 1809. The Gazetteer of 1907 (a form of geographical index) says that the riots took place over the attempt to make a Hanuman shrine on the “neutral ground” between the Gyanvapi mosque and the Vishweshwar temple, “the most sacred spot in the whole city”. Several hundred were killed.

When historian Gyanendra Pandey went over earlier records of the riots here, he found something entirely different — that the site was the Lat Bhairon Temple “a mile outside the limits of the city”, which every colonial record of the riot had been saying for a century. Singh also confirmed that the riots of 1809 were indeed at the Lat Bhairon. But in the Gazetteer , it was suddenly displaced and brought to the Vishwanath temple. British administrators messed up, too.

What colonial records do provide is a large repository of detail that is otherwise hard to reconstruct. In the first half of the 20th century, for instance, they recorded conflicts in the Gyanvapi area over the mosque but the stories also show two things — that people did come together to quell them and, it seems, that they can only be read as subjective accounts, not objective truths.

A confidential home department report from 1918 (now in the public domain with the National Archives of India) said that a “local firebrand” called Muhammad Sadiq had planned on talking about jihad at the Gyanvapi mosque. “But [he] was not allowed to speak by the Pesh Imam.”

Then in 1923, another secret report wrote, Muslims of the Gyanvapi area wanted to cut a peepal tree at the mosque. “Hindus from the villages armed with lathis assembled in numbers” but the threat of violence passed.

A decade later, an internal report from 1935 said that there was a “riot” in Varanasi. Worshippers at the Gyanvapi mosque were “not allowed to overflow from the mosque into the square” for Alvida prayers, the last Friday prayers before Eid. That square was a space through which Hindus entered their temple. When Muslim worshippers did spill on to the streets, the police intervened and the protesters were fined Rs 800. But, the report says, the demonstration was “confined to only a small section”.

Yet, it was recorded as a riot. A sense of proportion is not always to be assumed.

Besides Prinsep, Singh, formerly of BHU, referred to two texts that I came to realise hold significance for a lot of people in Varanasi. Kashi Khand , which is a section of the religious text Skanda Purana , and Motichandra’s Kashi ka Itihas (History of Kashi). About “unparalleled” Motichandra, Singh says, “It is like our Bible. No book like this has ever been written.” So, what do the ‘Bibles of Kashi’ say?

I go looking for them. I enter a religious book store. “What is your bestselling book on Varanasi?” I ask the store owner. He hands me an annotated edition of Kashi Khand . Next, I stop at a bookstore near Assi Ghat. “Motilal?” I ask, getting the name completely wrong. The store assistant knew what I was asking for and got me Kashi ka Itihas . “Sales of all books on Varanasi have gone up over the past month,” the proprietor says while handing me the bill. The dispute has meant good business.

Kashi ka Itihas is now in its fifth edition, with an uninterrupted run since 1962. It does intermittently cite sources but not always. As I read it, I realise that its ubiquity has more to do with its simplicity of storytelling than loyalty to sources. And it is here that references to demolished temples and expansionist mosques gain currency in popular imagination. This is a translation of what the bestselling book says after citing the Maasir-i-Alamgiri section quoted earlier:

The temple was not just demolished but also replaced with a mosque. Those building the mosque brought down the western wall of the temple and buried the smaller temples. The gates to the west, north and south were shut and their towers destroyed. Domes were installed in their place. The temple’s sanctum sanctorum became the courtyard of the mosque. The four antargriha [it could mean inner chambers or cellars] were preserved.

The timeline it mentions is what Singh recounted, adding Maharaja Ranjit Singh got its spires gilded and that the Nandi idol was installed by the king of Nepal at the beginning of the 19th century.

The specific sources for these details are not mentioned. While Kashi ka Itihas is meant to be a history book, the Kashi Khand is a collection of religious verses believed to have been compiled between 9th and 15th century CE. They form a part of the Skand Purana . Elements from that have been used to say that a temple did exist where a mosque now stands. This is a translation of what it says about the location of the temple: South of the Avimukteshwara is a magnificent well, whose waters free people of the cycle of life and death. In the hearts of those who drink this water emerge three lingas. The waters of this well are protected by Dandapani to the west, Tarakeshwar to the east, Nandishwar to the north and Mahakaleshwar to the south . But it is part of a much more elaborate mythology of love and rebirth.

A brahman of Kashi, Hariswami, had a daughter, Sushila. Of beauty unexcelled. She would take a bath in the Gyanvapi every day and then clean the premises of the temple of Shiva. She never looked at anyone, never listened to what anyone said and never reciprocated the innumerable propositions of love she received. But one night while she was asleep, a man named Vidyadhara abducted her.

The time he chose was also one picked by the demon Vidyunmali. He attacked Vidyadhara with a trishul. Vidyadhara hit back and killed the demon. But the injury received was fatal and Vidyadhara died, with Sushila’s name on his lips. Sushila spent the rest of her life considering Vidyadhara as her husband.

Years passed. Vidyadhara was reborn as the southern king Malyaketu and Sushila was reborn as Kalavati. They got married and had three sons, unaware of the union they had been denied in their past life. Then one day, a painter from the north presented a painting to Malyaketu. It was glorious. And he gifted it to Kalavati. When she saw it, she went into a trance, reciting the name of every god in Kashi. It was a painting of Gyanvapi.

“Kalavati spotted Gyanvapi to the south of Sri Vishweshwara. Dandanayaka, Sambhrama and Vibhrama make the evil-minded ones extremely confused and protect the waters of Gyanvapi from them…This Gyanvapi, bestower of knowledge, is the aquatic physical form of the eight-formed Mahadeva cited in the Puranas .”

An attendant, Buddhisaririni, then suggested that perhaps touching the painting would bring her to her senses. They did. She regained consciousness and “by touching the Vapi in the picture, she obtained the knowledge of her previous birth and of everything in the previous birth.”

Her attendants wanted to see this miraculous well too. She took their request to her husband, the king. Malyaketu heard her, renounced his kingdom and retired to Varanasi with her. They spent the rest of their lives worshipping the temple at Gyanvapi, renovated the Gyanvapi steps with jewels and, when they got old, a chariot from heaven took them away.

It is, quite plainly, a mythological story. So, when I read the persistently cited James Prinsep’s account of Benares and found that the “fabulous wonders” of Kashi Khand inform parts of his narrative just as much as actual historical records, I was confounded.

The legal validity of it all is what I had to understand.

But nowhere in any discussion could I find the answer to two questions on history and religion. That a temple was demolished might be proven with records, but is there any evidence if the mosque came up exactly there? And if the structure found within the mosque is the “original” shivling , what does that make the one being worshipped at Vishwanath Temple?

(Illustrations: Sajeev Kumarapuram)

ASI survey, released in 2024

A

Asad Rehman, Jan 27, 2024: The Indian Express

In a report on its scientific survey of the mosque complex – it’s in four volumes – the ASI, tasked by the Varanasi district court to ascertain whether the mosque was “constructed over a pre-existing structure of a Hindu temple”, has concluded just that, and describes a temple that existed before it “appears to have been destroyed in the 17th century, during the reign of Aurangzeb and part of it… modified and reused in the existing structure”.

Hindu litigants have claimed that the Gyanvapi mosque was built on the site of the earlier Kashi Vishwanath temple after its destruction in the 17th century.

The ASI report, made public Thursday after its copies were handed over to Hindu and Muslim litigants by the court, in the section titled ‘Reply to Observations of the Court’, stated: “Based on the studies carried out, observations made on the existing structures, exposed features, and artefacts studied, it can be concluded that there existed a large Hindu temple prior to the construction of the existing structure.”

“This temple had a big central chamber and based on the study of the existing structures and available evidence it can be concluded that it had at least one chamber to the north, south, east and west respectively,” it stated.

“Remains of three chambers to the north, south and west can still be seen but the remains of the chamber to the east and any further extension of it cannot be ascertained physically as the area to the east is covered under (a) solid functional platform with stone flooring,” it stated.

“Entrance to the central chamber of the temple was from (the) west which has been blocked by stone masonry. Its western chamber was also connected with north and south chambers through a corridor accessible from its north and south entrances respectively.”

“Main entrance to the central chamber was tastefully decorated with carvings of animals and birds and an ornamental torana. Figure carved on the lalatabimba has been chopped off and most of it is covered with stones, bricks and mortar which is used to block the entrance. Remains of a bird figure carved on the door sill, and part of which survived at the northern side, appears to be of a cock,” it stated.

Concluding that the western wall of the Gyanvapi mosque was the “remaining part of a pre-existing Hindu temple”, the ASI said, “Art and architecture of any building not only indicates its date but also its nature. Karna-ratha and prati-ratha of central chamber visible on either side of western chamber, a large decorated entrance gateway on the eastern wall of the western chamber, a smaller entrance and destroyed image on lalatabimba, birds and animals carved for decoration suggest that the western wall is remaining part of a pre-existing Hindu temple.”

On the pillars in the mosque complex, the report stated: “From the minute study of these pillars, it is found that pillars with (a) square section having lotus medallion in the centre and flower bud chains on the corners, were part of the pre-existing Hindu temple. These pillars and pilasters are reused in the existing structure after removing vyala figures and converting that space in floral design. The observation is supported by two similar pilasters still existing on the northern and southern wall of the western chamber in their original place. This similarity is established on the basis of scientific study, art and design.”

The first volume of the ASI report is divided into three main categories: Introduction, Structures, Summary.

Under Introduction, it has the subheads – Court directive and Compliance, Constraints, Location, Settlement Plot number 9130, and Study Area. Under Structures, it has the subheads – Cellars, Existing Structure, Pillars and Pilasters, Western Wall, Inscriptions, Mason’s Marks, Measurements. Under Summary, it has the subheads – Reply to Observations of the Court, Brief Findings of the Survey. The first volume comprises 137 pages.

The second volume is on Scientific Studies and has the following subheads: Cleaning Operations and Finds, Scientific Investigations/Survey, X-Ray Fluorescence Report, Ground Penetration Radar Survey, Condition Report, Field Laboratory and Relative Humidity and Temperature. The second volume has 196 pages.

The third volume has Objects as the main heading and the following subheads: Artefacts, Retrieved Objects, Architectural Members. The third volume has 227 pages.

The fourth volume contains illustrations, with subheads Images and Figures. It has 238 pages.

The survey was undertaken by a team led by ASI Additional Director-General Alok Tripathi.

During the study, objects like inscriptions, sculptures, coins, pottery, architectural fragments and objects of terracotta, stone, metal and glass were examined and analysed.

According to the report, objects that required first-aid treatment were treated at the site. It stated that “archaeologists, epigraphists, chemists, engineers, surveyors, photographers, and other officials of the ASI and scientists of the National Geophysical Research Institute (NGRI), Hyderabad carried out investigations and collected data” which were “systematically analysed”.

Scientific studies were carried out in a 2150-sqm area, fenced by a steel grill around the existing structure, the report stated, adding that the “survey team established a reference point and prepared a plan of the entire complex”.

B

Note of caution: the Times of India article below is based entirely on a briefing by the Hindu side's lawyer Vishnu Shankar Jain

‘THE WESTERN WALL OF EXISTING STRUCTURE IS REMAINING PART OF PRE-EXISTING HINDU TEMPLE’

SURVEY HIGHLIGHTS

THE SURVEY | Carried out by the ASI in compliance with the Varanasi dist court's July 21, 2023 order, and later affirmed by Allahabad high court and the Supreme Court

THE AREA | Scientific investigation/ survey in 2150.5 sqm area fenced with steel grill, in and around the existing structure, excluding the wuzu pond area sealed by the SC order

SURVEYED OBJECTS | Inscriptions, sculptures, coins, architectural fragments, pottery, and objects of terracotta, stone, metal and glass. Objects which required first aid treatment were treated at the site. Scientific investigations were done while ensuring that no damage was caused to existing structure

SALIENT POINTS

GPR SURVEY | The survey in the north hall indicated a small sinkhole-type cavity in the floor at 1-2 m depth towards the northern door, a steep and deep narrow cavity adjacent to the central hall passage, and the floor having a larger accumulation of mortar bed thickness PRE-EXISTING STRUCTURE

Several pre-existing structures were found which prove that there existed a large Hindu temple, prior to the construction of the existing structure:

➤Central chamber and main entrance of the pre-existing structure in existing structure

➤ Western chamber and western wall Reuse of pillars and pilasters of preexisting structure in existing structure

➤ Inscriptions on the existing structure

➤ Arabic and Persian inscription on the loose stone

➤ Sculptural remains in cellars, etc

CENTRAL CHAMBER & MAIN ENTRANCE

➤ This temple had a big central chamber and at least one chamber to the north, south, east and west respectively. Remains of three chambers to the north, south and west still exist but the remains of the chamber to the east and any further extension of it could not be ascertained physically, as the area is covered under a platform with stone flooring. Central chamber of the preexisting structure forms the central hall of the existing structure. This structure with thick and strong walls, along with all architectural components and floral decorations was utilised as the main hall of the mosque. Animal figures carved at the lower ends of decorated arches of the pre-existing structure were mutilated, and inner part of dome is decorated with geometric designs

Main entrance to the central chamber of the temple was from the west which was blocked by stone masonry. This entrance was decorated with carvings of animals and birds and an ornamental torana. This large arched gateway had another smaller entrance. Figure carved on the lalatbimba of this small entrance has been chopped off. A small part of it is visible as most of it is covered with bricks, stone and mortar which were used to block the entrance

WESTERN CHAMBER & WESTERN WALL

➤ Eastern half of the western chamber still exists whereas the superstructure of western half has been destroyed. This chamber was also connected with north and south chambers through a corridor accessible from its north and south entrances respectively. Remains of this corridor in the northwest side came to light on removal of garbage and debris

➤ The western wall of the existing structure is the remaining part of a preexisting Hindu temple. This wall, made of stones and decorated with horizontal mouldings, is formed by remaining parts of western chamber, western projections of the central chamber and western walls of the two chambers on its north and south. Central chamber attached to the wall still exists unchanged whereas modifications have been made to both the side chambers

➤ All these chambers had an opening in all the four directions. Decorated arched entrances of central, north and south chambers towards west have been blocked. The arched openings of north and south halls were converted into steps leading to the roof. Steps made in the arched entrance of the north hall are still in use. Steps made in the arched entrance of the south half were blocked by stone masonry at the roof

PILLARS & PILASTERS

For the enlargement of the mosque and constructing sahan, parts of the pre-existing temple including pillars and pilasters were reused with little modifications. Minute study of the pillars and pilasters in the corridor suggest that they were originally part of the preexisting Hindu temple. For their reuse in the existing structure, vyala figures carved on either side of lotus medallion were mutilated and after removing the stone mass from the corners that space was decorated with floral design. This observation is supported by two similar pilasters still existing on the northern and southern wall of the western chamber in their original place

INSCRIPTIONS

➤ During the survey, a number of inscriptions were noticed on the existing and pre-existing structures. A total of 34 inscriptions were recorded during the present survey and 32 estampages were taken. These are, in fact, inscriptions on the stones of the pre-existing Hindu temples, which have been re-used during the construction/ repair of the existing structure. They include inscriptions in Devanagari, Grantha, Telugu and Kannada scripts. Reuse of earlier inscriptions in the structure suggest that the earlier structures were destroyed and their parts were reused in construction/ repair of the existing structure. Three names of deities such as Janardhana, Rudra, and Umesvara are found in these inscriptions. Terms such as Maha-muktimandapa mentioned in three inscriptions is of great significance Inscription On Loose Stone

➤ An inscription engraved on a loose stone which recorded construction of the mosque in the 20th regnal year of Hadrat Alamgir i.e., Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb corresponding to A.H. 1087 (1676-77 CE). This inscription also recorded that in the year A.H. 1207 (1792-93 CE), the mosque was repaired with sahan, etc. The photograph of this stone inscription was recorded in ASI records in the year 1965-66

➤ During the recent survey, this stone with inscription was recovered from a room in the mosque. However, the lines relating to construction of the mosque and its expansion have been scratched out

➤ This is also brought out by the biography of Emperor Aurangzeb, Maasir-i-Alamgiri, which mentions that Aurangzeb "issued orders to the governors of all the provinces to demolish the schools and temples of the infidels" (Jadu Nath Sarkar (tr.) 1947, Maasir-iAlamgiri, pp. 51-52). On September 2, 1669 "it was reported that, according to the Emperor's command his officers had demolished the temple of Viswanath at Kashi" (Jadu Nath Sarkar (tr.) 1947, Maasir-i-Alamgiri)

SCULPTURAL REMAINS IN CELLARS

➤ A series of cellars were also constructed to the east to create additional space and a large platform in front of the mosque for accommodating large number of people for prayers

➤Pillars from earlier temples were reused while making cellars in the eastern part of the platform. A pillar decorated with bells, niches for keeping lamps on all four sides, and bearing an inscription of Sarhvat 1669 (corresponding to 1613 CE, January 1, Friday) is reused in cellar N2

➤ Sculptures of Hindu deities and carved architectural members were found buried under the dumped soil in cellar S2

NATURE AND AGE

➤ Existing architectural remains, decorated mouldings on the walls, karna-ratha and prati-ratha of central chamber, a large decorated entrance gate with torana on the eastern wall of the western chamber, a small entrance with mutilated image on lalat bimba, birds and animals carved for decoration in and outside suggest that the western wall is remaining part of a Hindu temple. Based on art and architecture, this pre-existing structure can be identified as a Hindu temple

➤ The Arabic-Persian inscription found inside a room mentions that the mosque was built in the 20th regnal year of Aurangzeb (1676-77 CE). Hence, the preexisting structure appears to have been destroyed in the 17th century, during the reign of Aurangzeb, and part of it was modified and reused in the existing structure

CONCLUSION

Based on scientific studies/ survey carried out, study of architectural remains, exposed features and artefacts, inscriptions, art and sculptures, it can be said that there existed a Hindu temple prior to the construction of the existing structure (According to briefing by Hindu side's lawyer Vishnu Shankar Jain)

C

Asad Rehman, Jan 28, 2024: The Indian Express

As per Volume 3, one “Makara” stone sculpture, one “Dwarpala”, one “Apasmara Purusha”, one “Votive shrine”, 14 “fragments”, and seven “miscellaneous” stone sculptures were also found during the ASI survey.

The ASI, tasked by the Varanasi district court to ascertain whether the mosque was “constructed over a pre-existing structure of a Hindu temple”, has concluded that a temple “appears to have been destroyed in the 17th century, during the reign of Aurangzeb and part of it… modified and reused in the existing structure”. The ASI report — it’s in four volumes — was made public Thursday after copies of it were handed over to Hindu and Muslim litigants by the court.

As per Volume 3, one “Makara” stone sculpture, one “Dwarpala”, one “Apasmara Purusha”, one “Votive shrine”, 14 “fragments”, and seven “miscellaneous” stone sculptures were also found during the ASI survey.

A total of 259 “stone objects” were found, including the 55 stone sculptures, 21 household materials, five “inscribed slabs” and 176 “architectural members”. A total of 27 terracotta objects, 23 terracotta figurines (two of gods and goddesses, 18 human figurines and three animal figurines) were also found and studied during the survey, states the report.

A total of 113 metal objects, and 93 coins — including 40 of the East India Company, 21 Victoria Queen coins and three Shah Alam Badshah-II coins — were found and studied during the survey. All objects recovered during the survey were later handed over to the Varanasi district administration, which has stored them. The report states one of the sculptures of Krishna is made of sandstone and belongs to the late medieval period. It was found in the eastern side of cellar S2, and its dimensions are: height 15 cm, width 8 cm, and thickness 5 cm.

Its description reads: “The extant part depicts a headless male deity. Both the hands are broken, but the right hand appears to be raised. The left hand appears to go over the body. The right leg is extant above the knee. The left leg is broken at the hip. Based on the posture and iconographic features, it appears to be an image of Lord Krishna. He is depicted wearing necklace, yajnopavita and dhoti.” It is in “good” condition.

Another sculpture listed in the report of Hanuman, made of marble. Its date/period is written as “modern”, and was located in the northwest side. Its measuresments are: height 21.5 cm, width 16 cm, and thickness 5 cm. Its description reads: “The extant part depicts the bottom half of a sculpture of Hanuman. The left leg bent at the knee is placed on a rock. The right leg is firmly planted on the ground.” Its in “good” condition.

A “shiva linga” listed in the report is made of sandstone, its date/period is modern, and location was the “western chamber”. Its description says: “A broken piece of a cylindrical stone object with convex top, most probably a shiva linga. It is broken at the base and some chipping marks can be seen on the top and side.” Its height is 6.5 cm, and diameter 3.5 cm. The condition is “good”.

Another sculpture of “Vishnu” is made of sandstone, and its date/period is written as early medieval. Its description reads: “Broken part of a back slab (parikara) of a Brahminical image. The extant part exhibits the image of four-handed crowned and bejeweled Vishnu seated in ardhyaparyankasana posture. The upper right hand holds the gada, the lower hand is broken at the palm. The upper hand has a chakra and lower left hand has shankha. Flying vidhyadhara couple is seen on the top and a standing attendant figure to the extreme left. His right hand is raised above the head. Right leg is bent at the knee and upraised.” The dimensions are: height 27 cm, width 17 cm, and thickness 15 cm; and its condition is “good”.

On a sculpture of Ganesha, it states: “The extant part depicts the crowned head of Ganesha. The trunk is turned to the right. The eyes are visible. Part of the left trunk is also extant.” Its condition is “good”. This was found in the western side of cellar S2 and is listed as a “late medieval”. Made of marble, its dimensions are: height 12 cm, width 8 cm, and thickness 5 cm.

The dispute

A backgrounder

Prabhash K Dutta, May 15, 2022: The Times of India

From: Prabhash K Dutta, May 15, 2022: The Times of India

Varanasi’s Gyanvapi shrine premises is one such emotive subject that is being debated today. This complex houses religious places of Hindus and Muslim — Gyanvapi Masjid (or, Anjuman Intezamia Masajid) which is adjacent to the famous Kashi Vishwanath temple, where resides Lord Shiva, the presiding deity of Varanasi. Behind the western wall of the Gyanvapi mosque is Shringar Gauri which houses the statues of Shringar Gauri (mother goddess), Lord Ganesha, Lord Hanuman and Nandi, the constant companion of Lord Shiva.

Gyanvapi masjid-Kashi Vishwanath temple complex is currently under judicial scrutiny and archaeological inspection primarily over two bunches of petitions. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), however, has nothing to do with the survey as of now. It is also not an ASI-protected site. But before we go into claims and counter-claims, let us first have a look at the history.

History behind Gyanvapi

In ancient times, temples used to be the centres of learning and culture. Kashi, as Varanasi was more famously known in earlier times, is one of the oldest cities and centres of learning. The name, Gyanvapi translates to the well of knowledge or a place of learning. There is a well on the premises.

Historians are divided on the date and the nature of the original structure at the site. But it is believed that the Gyanvapi mosque was built in 1669 during the reign of Aurangzeb, the Mughal emperor who ruled between 1658 and 1707.

The historical debate is whether he built this mosque by demolishing an earlier temple or the two developments (demolition and construction) happened separately. The Hindu side believes that the lingam of the older temple was hidden by the priests in the well (Gyanvapi) when the structure was demolished.

That the temple was demolished on the orders of Aurangzeb was mentioned in a 1937 book titled, History of Benares: From the Earliest Times Down to 1937 , written by AS Altekar, who was head of the Department of Ancient Indian History and Culture at Banaras Hindu University (BHU). The existing place was then called the Vishweshwar temple.

A longer history

There is another belief that the Gyanvapi site housed an ancient temple, portions of which was destroyed during the invasion by Muhammad Ghori in 1194. The ancient temple was built by one of the Vikramaditya kings.

Later in the 14th century, Jaunpur’s Sharqi sultan Muhammad Shah destroyed the temple to build the Gyanvapi mosque. The temple was reconstructed or renovated in 1585 with the permission of Mughal emperor Akbar, who was following the policy of sulah-e-kul (universal peace), by his minister Raja Todarmal. It was this temple of Lord Shiva that Aurangzeb apparently ordered to demolish. A chronicler of the time, Saqi Mustaid Khan in his Maasir-e-Alamgiri has mentioned about the temple demolition. Its translation, by historian Sir Jadunath Sarkar, shows the record of September 2, 1669, as: “It was reported that, according to the Emperor’s command, his officers had demolished the temple of Viswanath at Kashi.”

The other viewpoint is that both Kashi Vishwanath temple and the Gyanvapi mosque were constructed by Akbar as part of his experiment of religious toleration. The Anjuman Intezamia Masajid Committee, in-charge of the Gyanvapi mosque, has maintained this stand.

Yet another version of history says that Aurangzeb ordered demolition of the temple but the Gyanvapi mosque was built separately, and has been in use for offering namaz since 1669. The dispute over offering prayers in this contentious place of worship is not new, as seen in this TOI news report dated December 20, 1935 The dispute

The religious structures have stayed side-by-side since the days of Mughal decline. A legal dispute emerged in 1991 when three local residents — Harihar Pandey, Somnath Vyas and Ramrang Sharma — moved a Varanasi court seeking permission for worship in the area of the Gyanvapi mosque contending that it was the original site of Kashi Vishwanath temple.

The mosque management committee opposed the petition dismissing the claims made by the petitioners.

Later, Varanasi-based lawyer Vijay Shankar Rastogi approached the court as the “next friend” of the presiding deity of the Kashi Vishwanath temple. In legal terms, ‘next friend’ is a person who represents someone not capable of maintaining his or her suit directly in court. Petitioner and counsel Rastogi represents deity Swayambhu Jyotirling Bhagwan Vishweshwar in the case. This news report dated August 2, 1995, highlights the Hindutva brigade's interest in the Gyanvapi mosque. As a senior VHP leader, the late Ashok Singhal was instrumental in the 'kar sewak' campaign that led to the Babri Masjid demolition

It was in this case that the Varanasi court in April 2021 ordered an ASI-monitored survey of the Gyanvapi premises. The mosque committee moved the Allahabad high court against the civil court order and secured a stay on the archaeological survey of the site in September 2021.

The claim

The petitioners claimed that the Gyanvapi mosque was the original sanctum sanctorum of the original Vishweshwar temple. They cite the positioning of Nandi statue, which faces the Gyanvapi mosque, not the present Kashi Vishwanath temple.

The claim got support from historian Audrey Truschke, who in her book — Aurangzeb: The Man and the Myth — writes, “My understanding is that the Gyanvapi masjid was indeed built during Aurangzeb’s reign. The masjid incorporates the old Viswanath temple structure — destroyed on Aurangzeb’s orders — as its qibla wall. While the mosque dates back to Aurangzeb’s period, we do not know who built it.”

The famed Nandi bull statue at the Kashi Vishwanath temple, which faces the Gyanvapi mosque (Pic: Wikidata) The mosque committee rejects this claim as manufactured by the petitioners and without any historical evidence.

The other case There is another case in which the Varanasi court on Thursday set May 17 as the deadline for video inspection of the Gyanvapi premises to ascertain the religious nature of the site. The mosque side had opposed videography of the survey and also sought inspection to be restricted inside the structure.

This case relates to a petition filed by five women devotees — one from Delhi, four from Varanasi — who sought permission for daily worship and performing rituals throughout the year at Shringar Gauri, which is behind the western wall of the Gyanvapi mosque.

The site currently opens for worship for the Hindus once a year on the fourth day of the Chaitra navratri (usually falls in April).

The petition was filed last year and the court had in August 2021 ordered a three-day inspection. An advocate commissioner was appointed to complete the survey, which could not happen. In April this year, the court appointed Ajay Mishra as the advocate commissioner for completing the survey. The mosque side opposed the inspection under Mishra’s supervision alleging that he was prejudiced against them. The attempt to film the survey created a row bringing the court in picture again.

On May 12, the Varanasi court though refused to replace Mishra as the advocate commissioner, it appointed a special advocate commissioner and an assistant advocate commissioner to oversee the survey and filming of the entire process.

What may be the outcome?

Given the emotive nature of the temple-mosque dispute in India, a law, called the Places of Worship Act, was passed in 1991 – the same year as the Gyanvapi dispute reached the court — by the then PV Narasimha Rao government. The Act says the nature of a religious structure as it existed on August 15, 1947 cannot be changed. Ayodhya’s Babri Masjid-Ram Janmabhoomi dispute was kept out of the purview of the Act.

But the petitioners in the Gyanvapi dispute contend that the 1991 law does not apply in this case. Their argument is that the Gyanvapi structure is not a mosque. However, the Allahabad high court invoked the same law in 1993 giving relief to the mosque management committee, which had approached it against hearing on the plea made by the three petitioners in the Varanasi court. Many years later in 2018, the petitioners secured clearance from the Supreme Court for hearing in the Varanasi court, which began its hearing in 2019 and ordered an ASI-monitored survey in 2021. While the 1991 law enforces status quo at all pre-Independence places of worship, the Supreme Court in March 2021 agreed to examine the constitutional validity of the Places of Worship Act. An outcome of that legal scrutiny may decide what happens to the Gyanvapi dispute.

1936 case

Prabhash K Dutta, June 10, 2022: The Times of India

This case was filed by one Deen Mohammad, who in 1936 moved a local court in Varanasi (Benares), claiming that the land on which the Gyanvapi mosque stood and enclosure around it belonged to the waqf. The lower court heard the arguments, examined historical documents and dismissed the plea saying the land around the mosque was not a waqf property.

Unsatisfied, Deen Mohammad challenged the Varanasi court order in the Allahabad high court in 1937. The high court delivered its verdict in 1942. It, too, dismissed the petition ruling that the land around the mosque was not a waqf property. The basement of the mosque was also not held as a waqf property.

The high court, however, ruled that the Muslims had the right to offer namaz at the structure of the Gyanvapi mosque, maintained by Anjuman Intejamia Masjid.

This is the part of the 1942 judgment that the Muslim side has cited in the courts now to assert that the mosque, courtyard and the land on which the mosque exists is a property of waqf. This means that the petitions by the Hindus challenging the Muslims’ rights on the Gyanvapi complex are not maintainable.

The 1942 ruling of the Allahabad high court that dealt with the ownership of the mosque and the land surrounding it

But the Hindus cite other portions of the judgment and point out that the Hindus were not impleaded in this suit.

In this debate, a question remains unanswered as to what prompted Deen Mohammad to move the court to claim title rights for the waqf over the land around the mosque? His was the first civil court case relating to the ownership of the Gyanvapi complex.

The riddle

The Allahabad high court ruling, which may be read here, gave a detailed description of the nature of dispute at the Gyanvapi complex. The court judgment talks about the dispute over the ownership and the right to worship and congregation at the Gyanvapi complex.

But the judge says, “I do not think it is necessary to go into the question of the origin of the mosque. It is sufficient to go back to the year 1809, when there was a serious riot between Hindus and Musalmans in that part of Benares where the mosque is situated.” These riots were related to the possession of the entire Gyanvapi structure.

The high court notes that the magistrate of Benares in 1809 and the acting magistrate in 1810 “had suggested that the Musalmans should be absolutely excluded from the mosque”. However, the British India government (Vice-President on the Council of Governor General of India) “disapproved of the suggestion” basing its opinion “on the obvious expediency” of maintaining public tranquility by not stoking “jealousy and discontent” among Hindus and Muslims.

The Allahabad high court judgment provides details of a number of administrative orders through the 19th century and the early 20th century – during which several attempts were made by both the Hindus and Muslims to take control of the entire enclosure around the Gyanvapi mosque.

On the basis of administrative inquiries and orders, the high court ruled that though the entire complex was not a waqf property, the Muslims congregated in large numbers at the mosque overflowing onto the adjoining enclosure particularly after 1929-30 to “establish some kind of claim over this land” despite orders to restrict their congregation within the mosque area.

It was against this background that Deen Mohammad moved his petition to claim the Gyanvapi complex as a waqf property. He sought exclusive rights of the Muslims on the entire Gyanvapi complex.

But, if it is decided that the mosque is the property of the waqf, what is the dispute now?

What is brewing now?

The 1991 case, the 2021 Shringar Gauri suit and the petition against the Places of Worship Act taken together may have a bearing on the ownership of the mosque structure. As of now, the mosque and the wazukhana (the area used for washing up before offering namaz) belong to the waqf. It was in this wazukhana area that the shivling was reportedly found by the court-appointed team that conducted a video-survey of the premises in May.

In the 1937 case, the Allahabad high court did not go into the origin of the dispute and hence, it did not settle the question whether the mosque structure originally belonged to the Hindus or the Muslims. This is the question that is now being debated in the courts in the two bunches of petitions directly linked to the Gyanvapi dispute.

As in 2021 April

From: Binay Singh, April 9, 2021: The Times of India

Uttar Pradesh: ASI probe ordered into Kashi Vishwanath temple-Gyanwapi mosque dispute

Binay Singh| TNN | Updated: Apr 8, 2021, 23:26 IST

The judge asked the Uttar Pradesh government to get examined the disputed premises by a five-member team of the Archaeological Survey of India. (File Photo)

1991- 2020

In 1991, the first petition was filed in Varanasi civil seeking permission for worship in Gyanvapi. The petitioner had contended that Kashi Vishwanath Temple was built by Maharaja Vikramaditya about 2,050 years ago, but Mughal emperor Aurangzeb destroyed the temple in 1664 and used its remains to construct a mosque, which is known as Gyanvapi masjid, on a portion of the temple land.

In 1998, Anjuman Intezamia Masjid Committee moved the high court contending the mandir-masjid dispute could not be adjudicated by a civil court as it was barred by law. The high court then stayed the proceedings in lower court . In February 2020, the petitioners approached the lower court again to resume hearing as the HC had not extended the stay in the preceding six month

Advocate Vijay Shankar Rastogi, as the ‘next friend’ of Swayambhu Jyotirlinga Bhagwan Vishweshwar, had filed an application in the court of civil judge in December 2019, requesting for survey of the entire Gyanvapi compound by the ASI. He also demanded the restoration of the land on which the mosque stood to the Hindus claiming that Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb had pulled down parts of the old Kashi Vishwanath Temple to build it.

In January 2020, defendant Anjuman Intezamia Masjid Committee filed an objection against the petition.

The petitioner had requested the court to issue directions for removal of the mosque from temple land and give back its possession to the temple trust. The petition contended that the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act was not applicable on the suit as the mosque was constructed over a partly demolished temple and many parts of the temple exist even today.

2021

VARANASI: A local court of civil judge on Thursday allowed a survey of entire Gyanvapi mosque complex, adjacent to the Kashi Vishwanath temple, by the Archaeological Survey of India to find out 'whether the religious structure standing at the present and disputed site is a superimposition, alteration or addition, or there is structural overlapping of any kind.

In its order, the court of civil judge (senior division), fast track, Ashutosh Tiwai, directed the ASI director general to constitute a five-member committee of eminent persons who are experts and well-versed in the science of archaeology, two of which should preferably belong to the minority community.

The committee shall trace whether any temple belonging to the Hindu community ever existed before the mosque in question was built or superimposed or added upon it at the disputed site, the order said.

In its order, the court also directed the DG to appoint an eminent and highly experienced person, who can be regarded as expert in the science of archaeology, to act as observer.

“Such person should preferably be a scholarly personality and established academician of any central university,” it said.

The five-member committee shall submit a report of its survey work to the observer on a daily basis.

The court further said the committee shall prepare comprehensive documentation along with the drawing, plan, elevation, site map with precise breadth and width of the disputed site, marked with hatched lines in the plaint map.

“The purpose of the archaeological survey shall be to find out as to whether the religious structure standing at the present and disputed site is a superimposition, alteration or addition or there is structural overlapping of any kind. If so, then what exactly is the age, size, monumental and architectural design or style of the religious structure, and what material has been used for building the same,” the court said.

For that purpose, the committee shall be entitled to enter into every portion of the religious structure, the order said.

The committee shall firstly resort to Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) or Geo-Radiology System or both to satisfy itself as to whether any excavation or extraction work is needed in any portion. The excavation should be done by trial trench method vertically on a very small scale, and horizontal excavation shall be done only when the committee is fully satisfied of being able to reach a more concrete conclusion regarding the archaeological remains below the ground.

1991 – 2023

Dec 20, 2023: The Times of India

3 decades of legal battle

October 15, 1991:

A plea is filed in Varanasi civil court on behalf of ‘the ancient idol of Swayambhu Jyotirlinga Bhagwan Vishweshwar’, and 5 others, demanding the restoration of the land on which Gyanvapi mosque was built to the adjacent to Kashi Vishwanath temple. It also sought removal of Muslims from the complex area, and demolition of the mosque, claiming that it was built after demolishing the Adi Vishweshwar temple

July 17, 1997:

Civil court dismisses the plea saying that it was not maintainable under the Places of Worship Act 1991, which mandates that the 1947 status quo of all religious places should be maintained. Petitioners move dist court. The AIM challenges their plea

September 23, 1998:

The dist judge orders the civil court to adjudicate the dispute afresh after considering all evidence. The AIM challenges the maintainability of the suit in Allahabad HC

October 13, 1998:

HC stays the Varanasi dist court order and further proceedings in the case. The stay remains in place for more than 21 years

November 9, 2019:

The SC order paves the way for the construction of Ram Temple in Ayodhya

December 2019:

A month later, Vijay Shankar Rastogi, who identifies himself the “next friend” of Swayambhu Jyotirlinga Bhagwan Vishweshwar, files fresh petition in the civil court seeking an ASI survey to find out whether the mosque was built over an ancient Hindu temple

February 2020:

The original petitioners approach the civil court again with a plea to resume the hearing as the HC had not extended the stay in the past six months. A 2018 ruling of the SC says that a stay should be rectified every 6 months

March 15, 2020:

AIM challenges this plea in HC which stays the proceedings in the original suit

April 8, 2021:

On Rastogi’s plea, Varanasi civil judge (senior division) Ashutosh Tiwari directs the ASI to conduct a scientific survey of Gyanvapi Complex. The AIM again moves the HC

September 9, 2021:

HC stays the civil court order for ASI survey. Justice Prakash Padia later clubs this with original suit and starts hearing

August 11, 2023:

CJ Pritinker Diwaker withdraws the case from Justice Padia ‘in the interest of judicial propriety, judicial discipline and transparency in the listing of cases’. The hearing continues in the CJ court

November 21, 2023:

The case is listed before Justice Rohit Ranjan Agarwal after retirement of Justice Diwaker

December 8, 2023:

HC reserves its order

December 14, 2023:

The plea of AIM and Sunni board challenging the maintainability of the original suit is dismissed

2023: Chief Justice transfers the case to another bench

Rajesh Kumar Pandey, Dec 20, 2023: The Times of India

PRAYAGRAJ: Judicial proceedings in the Kashi Vishwanath-Gyanvapi mosque dispute saw a curious turn in August this year when Pritinker Diwaker, Allahabad high court's the then chief justice, transferred the cases related to it to his bench from the bench of Justice Prakash Padia.

An administrative order highlighted concerns about the non-observance of proper procedures in listing the cases and the successive reservation of judgments.It emphasised that Justice Padia no longer had jurisdiction yet continued to hear the cases, leading to the chief justice's decision to withdraw them.

In a 12-page order, Chief Justice Diwaker explained that his decision stemmed from a complaint by a counsel involved in the proceedings, alleging that the hearing was not following the prescribed rules.

Anjuman Intezamia Masajid (AIM) and the UP Sunni Central Waqf Board approached the SC, arguing that the decision was unwarranted and would cause delays. However, in November, SC declined to intervene, with a three-judge bench led by Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud justifying the order by Chief Justice Diwaker due to Justice Padia's failure to deliver the judgment, despite reserving it in 2021 and holding 75 hearings.

Following Chief Justice Diwaker's retirement on November 21, the matter was assigned to Justice Rohit Ranjan Agarwal. After hearing all parties, he reserved judgment on December 8 and delivered the verdict on December 19.

Court judgements

Varanasi District Court

2022, September: three key issues

Sep 13, 2022: The Times of India

The Varanasi district court rejected on Monday a plea questioning the maintainability of a petition seeking permission for daily worship of Shringar Gauri and other deities whose idols are located on an outer wall of the Gyanvapi mosque. Judge AK Vishvesha dealt with 3 questions before arriving at his decision

1 Whether the suit is barred by The Places of Worship Act 1991?

What the order says:

➤“. . . The plaintiffs have not sought declaration or injunction over the property/land plot No. 9130. They have not sought the relief for converting the place of worship from a mosque to a temple. The plaintiffs are only demanding right to worship Maa Shringar Gauri and other visible and invisible deities which were being worshipped incessantly till 1993 and after 1993 till now once in a year under the regulatory of state of Uttar Pradesh. Therefore, the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991 doesnot operate as the bar on the suit of plaintiffs. The suit of the plaintiffs is limited and confined to the right of worship as a civil right and fundamental right as well as customary and religious right. I agree with the learned counsel for the plaintiffs”

➤“. . . The plaintiffs are…not claiming ownership over the disputed property. They have also not filed the suit for declaration that the disputed property is a temple”

➤“. . . In the present case, the plaintiffs are demanding the right to worship Maa Sringar Gauri, Lord Ganesh, Lord Hanuman at the disputed property, therefore, the civil court has jurisdiction to decide this case”

➤“Thus, according to plaintiffs, they worshipped Maa Shringar Gauri, Lord Hanuman at the disputed place regularly even after 15th August, 1947. Therefore, The Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991 does not operate as a bar on the suit of the plaintiffs and the suit of plaintiffs is not barred by Section 9 of the Act”

2 Whether suit is barred by Section 85 of the Waqf Act 1995?

What the order says (on AIM’s claim that Gyanvapi is a Waqf property):

➤ “I have come to the conclusion that the bar under Section 85 of the Waqf Act does not operate in the present case because the plaintiffs are non-Muslims and strangers to the alleged Waqf created at the disputed property and relief claimed in the suit is not covered under Sections 33, 35, 47, 48, 51, 54, 61, 64, 67, 72 & 73 of the Waqf Act. Hence, suit of the plaintiffs is not barred by Section 85 of the Waqf Act 1995”

3 Whether the suit is barred by the UP Sri Kashi Vishwanath Temple Act, 1983?

What the order says:

➤“From the perusal of (above mentioned) provisions of the Act, it is clear that no bar has been imposed by the Act regarding a suit claiming right to worship idols installed in the endowment within the premises of the temple, or outside. Therefore, defendant No. 4 failed to prove that the suit of the plaintiffs is barred by the UP Sri Kashi Vishwanath Temple Act, 1983”

Details

Rajeev Dikshit, Sep 13, 2022: The Times of India

Varanasi : The court of the Varanasi district judge held as maintainable a suit filed by five Hindu women seeking the right to daily worship of Goddess Shringar Gauri and other “visible and invisible” deities in the Gyanvapi mosque complex. It said the 1991Places of Worship Act cited by the custodians of the shrine to challenge the plea wasn’t a bar in the case as the plaintiffs never asked for the mosque to be converted into a temple. “According to the plaintiffs, they worshipped Maa Shringar Gauri, Lord Hanuman at the disputed place regularly even after 15th August, 1947. . . (hence) the suit of the plaintiffs is not barred by Section 9 of the Act,” district judge A K Vishvesha said, rejecting Anjuman Intezamia Masajid’s plea challenging the maintainability of the suit. Vishvesha, who took over the case from the civil judge (senior division) on the SC orders, will start hearing the original plea on Sept 22.

2024 Feb: MSY govt’s ’93 curbs on Gyanvapi puja illegal: HC

Rajesh Kumar Pandey & Dhananjay Mahapatra TNN, February 27, 2024: The Times of India

Prayagraj/New Delhi : The erstwhile Mulayam Singh Yadav-led UP govt’s act of stopping worship of Hindu deities by a family of priests in the southern cellar of Varanasi’s Gyanvapi Masjid in 1993 without a written order was illegal, Allahabad HC said Monday while dismissing Anjuman Intizamia Masjid’s (AIM) appeal challenging ex-district judge AK Vishvesha’s Jan 31 ruling allowing puja to resume.

Justice Rohit Ranjan Agarwal’s order describes the three-decade-old restrictions on the Vyas family, several generations of whom had been performing rituals until 1993 in a part of the basement known as “Vyas Ji Ka Tehkhana”, as “a continuous wrong being perpetuated”.

The 54-page ruling coincides with mosque custodian AIM moving Supreme Court, challenging another HC order from Dec last year dismissing its plea on the maintainability of the Hindu side’s original 1991 suit seeking to reclaim the site as the property of the deity Vishweshwar and his devotees. AIM’s fresh appeal adds another dimension to the already litigation-mired Gyanvapi row, including multiple pleas pending in SC against orders of a Varanasi trial court on the 2022 Shringar Gauri suit.

Kashi Vishwanath Corridor

From: Rajeev Dikshit, Lost and found: Varanasi temple route gets longer, November 28, 2018: The Times of India

In April, when hundreds of houses were demolished in Varanasi to build a corridor between Kashi Vishwanath temple and the Ganga ghats, both the administration and experts had not expected to come upon a trove of architectural marvels so rich. Seven months into the project, so many 18th century temples — several in immaculate condition — have been found in the bylanes of the holy city that the authorities are now planning to throw them open for worship once again.

Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has already identified 43 of them for prayer and preservation. These will be made part of the larger Kashi Vishwanath pilgrimage route.

The finds have been considered so valuable that the detailed project report of the Kashi Vishwanath Corridor (KVC) project has been amended to include these temples. “Our team is preparing a list of these structures with their architectural details in order to finalise a conservation plan,” said Niraj Sinha, in-charge of ASI’s Varanasi office. After a conservation plan is finalised, the temples will be opened for the public to conduct rituals and worship, a senior Kashi Vishwanath Temple Trust official said.

Work on the KVC project had begun earlier this year. The biggest hurdles for the corridor were the houses on the narrow lanes leading from the temple to the river. Approximately 296 private residences and commercial buildings were identified for demolition.

While a few old temples were found in the first round of the demolition drive, their number surged in the second round, which started in November. Most of these have been identified as 18th century temples. Inside dingy houses, buried under layers of concrete and plaster are beautiful brick and stone temples. One of the temples had been covered up for a house and had a toilet built on top of its ‘shikhara’ (pinnacle).

Shringar Gauri

The case: 1984- 2022

Rajeev Dikshit, May 23, 2022: The Times of India

Varanasi:The genesis of the Shringar Gauri worship case that has spawned a welter of legal and other complexities goes back 38 years, long before the five women plaintiffs approached a Varanasi court in April last year seeking the right to unhindered worship of the goddess and other deities along the outer wall of the Gyanvapi mosque complex.

Among those at the vanguard of the campaign from the start is Sohan Lal Arya, vicepresident of VHP’s Kashi chapter and husband of one of the plaintiffs, Laxmi Devi. “I was inspired by the late Mahant Paramhans Das’s role in placing Ram Lalla under the central dome at Ram Janmabhoomi, and started looking for ways to resume worship of deities at the mosque complex,” he said.

Clarifying that VHP had no role in the case, Arya said, “In 1984, I started meeting people who I presumed could help collect facts to start court proceedings. But that didn’t work out. Finally, I met a senior shastri of the Vedic study centre, who told me about the ground realities of the Gyanvapi complex”.

Temples in the nagara style of architecture have eight mandaps — Ganesha, Aishwarya, Bhairav, Gyan, Tarkeshwar, Mukti, Dandapani and Shringar, Arya said. “When the Aadi Vishweshwar temple was attacked by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in 1669, he destroyed the Aishwarya and Mukti mandaps along with the sanctum sanctorum of the temple to build a mosque. ”

The Ganesh, Shringar and Dandapani mandaps in the west and the Bhairav, Gyan and Tarkeshwar mandaps could not be destroyed, Arya said.

“In 1995, a petition was filed in the district court with the same demands. The court also appointed a commission, which surveyed the outer area in May 1996. But the survey of the internal area of Gyanvapi could not be done due to protests. ”

Arya was in Mathura in 2018-19 when he met Vishwa Vedic Sanatan Sangh (VVSS) chief Jitendra Singh Visen, who happened to know advocates Hari Shankar Jain and his son Vishnu Shankar Jain

Visen’s niece Rakhi Singh, Arya’s wife Laxmi Devi and Varanasi natives Sita Sahu, Manju Vyas and Rekha Pathak filed a petition in the court of the civil judge last year, seeking permission for daily worship of Shringar Gauri, Ganesh, Hanuman and Nandi, besides steps to prevent damage to the idols.

Southern cellar/ basement

A backgrounder

As in 2024 January

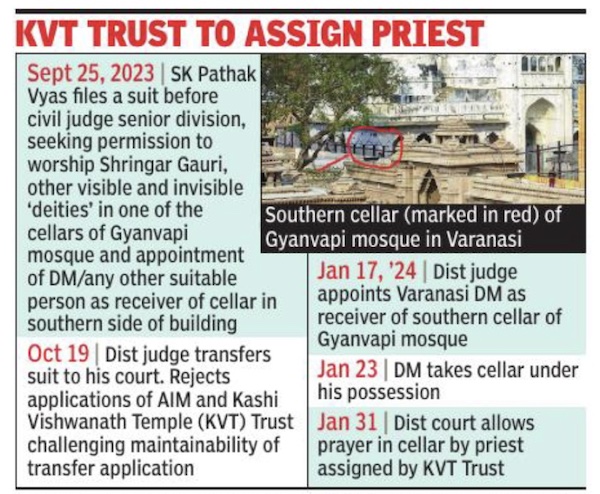

Lalmani Verma, Feb 1, 2024: The Indian Express

Why is a cellar inside the Gyanvapi mosque complex called 'Vyasji ka tehkhana'? What has the Varanasi court ordered, and what was the plea before it? We explain.

The order reads, “District Magistrate, Varanasi/Receiver is being directed to get puja, raag bhog done by a priest, designated by the plaintiff and Kashi Vishwanath Trust, of idols in the cellar to the south, which is disputed, of building situated on settlement plot no. 9130, police station Chowk, District Varanasi. For this, suitable arrangements must be made with iron barricading and other things within seven days.”

On January 24, the Varanasi district administration had taken possession of the southern cellar of the Gyanvapi mosque complex. This was following a Varanasi District Court order of January 17, through which it appointed the district magistrate of Varanasi as the receiver of the cellar, also called ‘Vyasji ka tehkhana’.

This case was filed by the head priest of Acharya Ved Vyas Peeth temple, Shailendra Pathak Vyas.

What is Vyasji ka tehkhana?

Vyasji ka tehkahana is located in the southern area of the mosque’s barricaded complex, facing the Nandi statue placed inside the Kashi Vishwanath complex near the sanctum sanctorum.

The tehkahana has a height of around 7 feet and carpet area of around 900 square feet. Subhash Chaturvedi, the lawyer of the petitioner Shailendra Pathak Vyas, said that the Vyas family had been conducting prayers and other rituals inside the tehkhana for more than 200 years, but the practice was stopped in December 1993.

He said that the tehkhana is located between the Nandi statue and the wuzookhana of the mosque, where Hindu petitioners have alleged that a shivling was found during a court mandated video-graphic survey in 2022.

Why was worship barred here?

The petitioner has argued that ‘Vyasji’s’ entry was prohibited in the tehkhana in December 1993, and hence the prayers being held here had to be discontinued.

On December 4, 1993, Mulayam Singh Yadav of the Samajwadi Party formed the government in UP, ending one year of President’s Rule, imposed after the Kalyan Singh government was dismissed in the wake of the Babri Mosque demolition in Ayodhya in 1992.

“The Mulayam Singh Yadav government prohibited worship inside the Vyasji ka tehkhana in the name of law and order. Before that, Pandit Somnath Vyas had carried out Hindi worship rituals here regularly,” Chaturvedi said.

Chaturvedi said that idols of Lord Hanuman, Ganesh, Shiva and other gods were worshipped inside the tehkhana and katha was preached there. He said during the recent ASI survey too, idols of various Hindu deities were found inside the tehkhana.

Who is the petitioner?

The petitioner Shailendra Pathak Vyas is the maternal grandson of Pandit Somnath Vyas. Shailendra is currently the head priest of the Acharya Ved Vyas Peeth in Shivpur area of Varanasi. His family had been provided space inside the tehkhana to worship, and hence the place was known as ‘Vyasji ki gaddi.”

Madan Mohan, a lawyer for the Hindu side in cases related to the Gyanvapi mosque, said the tehkhana was given to the Vyas family for worship and other religious rituals under the British in 1809.

“Somnath ji was a priest. He had been living near the Gyanvapi area. His family from several generations had been performing religious rituals inside the tehkhana,” Madan Mohan said.

2024 Jan: Court allows worship of Hindu deities in basement

Rajeev Dikshit, February 1, 2024: The Times of India

From: Rajeev Dikshit, February 1, 2024: The Times of India

Court allows worship of Hindu deities in Gyanvapi basement

Muslim Side To Move HC To Challenge Order

Varanasi : District judge Ajaya Krishna Vishvesha allowed regular worship of Shringar Gauri and other Hindu deities in the southern cellar of Varanasi’s Gyanvapi Masjid by a family of priests that used to perform rituals there prior to 1993.

The judge directed the district magistrate to make proper arrangements, including erecting an iron fence, within seven days so that the plaintiff — head priest Shailendra Kumar Pathak Vyas of Acharya Ved Vyas Peeth temple — and a priest assigned by Shri Kashi Vishwanath Temple Trust can resume daily worship.

Anjuman Intizamia Masajid (AIM), custodian of Gyanvapi mosque, later said that it would challenge the district judge’s order in Allahabad high court.

1993: Mulayam’s fence had stopped worship at cellar

The case is distinct from the Shringar Gauri litigation initiated by five Hindu women, seeking the right to unhindered daily worship of the deity and other idols within the Gyanvapi compound.

Shailendra Vyas’s plea states that his maternal grandfather, Somnath Vyas, would worship Shringar Gauri and other Hindu deities in the southern cellar until Dec 1993, when the then state administration barred entry into what purportedly used to be known as “Vyasji katehkhana”. The petition was admitted on Sept 25 last year, over two years after the main Shringar Gauri case was filed in the Varanasi civil judge’s court. District judge Vishvesha took over the Shringar Gauri case on the orders of SC and subsequently clubbed several civil suits linked to Gyanvapi.

Shailendra Vyas’s counsel Vishnu Shankar Jain said the plaintiff’s family had been visiting the southern cellar to worship the deities there “for centuries”. “In Dec 1993, the then Mulayam Singh Yadav government erected a steel fence without any judicial order, thus stopping the puja,” he said. Besides seeking access to the closed southern cellar of Gyanvapi, his client had petitioned the court to appoint the DM or any other appropriate authority as the “receiver” of that portion of the mosque. In a Jan 17 order, the district court appointed the DM as the receiver. The latter took custody of the southern cellar on Jan 23.

Before Shringar Gauri and seven other Gyanvapi-linked cases were transferred to district judge Vishvesha in 2022, the civil judge had ordered a court-monitored survey of the compound. The Hindu side claimed that a “Shivling” was found in the ablution pond of the mosque during the survey, which AIM challenged.

SC ordered the sealing of the pond area and transferred the case to the district judge on May 20, 2022.

YEAR-WISE DEVELOPMENTS

2021: Hindus, Muslims exchange land for Dham

Binay Singh, July 24, 2021: The Times of India

Just before the beginning of the holy month of Shravan, Shri Kashi Vishwanath Temple Trust (SKVTT) and the administration of the adjacent Gyanvapi mosque have entered a deal to exchange lands to facilitate the construction of the proposed Kashi Vishwanath Dham.

While the Gyanvapi adminitration is giving a piece of land measuring 1,700 squarefeet, for the development of Kashi Vishwanath Dham (corridor), the temple administration has given a piece of land measuring 1,000 square-feet to the Muslim community. The deal between the two parties was finalised on July 9.

However, the dispute between Kashi Vishwanath Temple (KVT) and Gyanvapi mosque regarding the survey of the entire premises by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) to find out whether a temple existed in place of the mosque is still in the court.

The exchange deal was signed by chief executive officer (CEO) of Shri Kashi Vishwanath Temple Trust, Sunil Kumar Verma, on behalf of the UP governor and Abdul Batin Nomani of the Anjuman Intezamiya Masajid, the management committee of the mosque.

Talking to TOI on Friday, divisional commissioner Deepak Agrawal said, “The property given by the Muslim side was owned by the Waqf Board and the Gyanvapi-KVT control room was situated on this land. Since the land was needed for the development of Kashi Vishwanath Dham, we offered a piece of land to them (Muslim community).”