Hapur district

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Sanitary pads

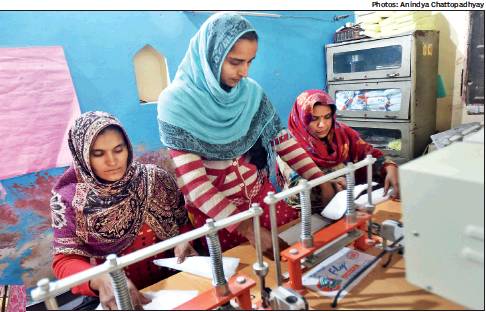

The workers, as in 2019

From: Sonam Joshi, How Hapur’s pad-women became stars of an Oscar-nominated docu, February 5, 2019: The Times of India

TOI meets the women who fought stigma and shame to work in a sanitary napkin factory in a UP village

Two girls giggle and hide their faces when asked about sanitary pads. “I know what it is but I feel shy,” says another woman. When a group of schoolboys is questioned about periods, one replies, “Like a class period? The kind you ring a bell for?”

These are the opening scenes of ‘Period. End of Sentence’, the documentary which was recently nominated for an Oscar in the short subject category. It is based on the experiences of a group of young women at Kathikhera village near Hapur, UP, who start making sanitary napkins using low-cost machines invented by social entrepreneur and ‘Pad Man’ Arunachalam Muruganantham.

Two years after their lives were captured on film, a seven-member team of women is still hard at work to meet its daily target of 600 pads. Situated next to a buffalo enclosure, the two-room factory makes eco-friendly sanitary pads from scratch using wood pulp.

The pads are sold under the brand name Fly, with a packet of six costing Rs 30. “In the beginning, many girls didn’t even tell their families they were making pads out of shame,” says Suman, a worker with NGO Action India, in whose house the unit is located. Each worker makes Rs 2,000 a month. Rakhi, who wants to be a college lecturer, uses her earnings to pay for her MA studies. Arshi, a BSc student, wants to be a doctor.

Then, there is the documentary’s ‘star’ Sneha. The 23-year-old wants to join the police, which she considers her escape route from the social pressure of marriage. “When I began working here, I told my father that it was a diaper factory. I felt ashamed that people would wonder why this girl is talking about a topic like menstruation,” she says. “But I realised if I was embarrassed, how would I do my work?” She soon gathered the courage to broach the M word with her female relatives and friends, convincing them to adopt pads.

Sneha, who’s funding her coaching classes for competitive exams, says that though she has a supportive father, it felt good to be able to “do something on my own steam”.

If these girls can dream today, some of the credit goes to ten schoolgirls and their English teacher from a school in Los Angeles who raised money to donate a pad-making machine to Hapur after learning that many girls their age had to drop out of school because of periods. With their teacher Melissa Berton’s help, they partnered with NGOs Girls Learn International and Action India.

The latter has set up a second unit in neighbouring Sudhana village, where seven more women are working. Two more are in the pipeline. But manufacturing is only half the battle. More difficult is the job of convincing women to switch from cloth to sanitary napkins.

The Fly team offers door-to-door delivery, tapping into a network of Asha and anganwadi workers to distribute pads. “Girls are embarrassed to buy pads from shops,” says Sneha. “When they get it at home, it becomes much easier.” Currently, they sell 700-800 pads a month. A series of ongoing ‘Gyan Vigyan’ melas in Hapur villages educate locals about menstrual hygiene and puberty through charts and diagrams, and explain gender equality using the game of snakes and ladders. At a mela in Nawada village, a worried woman Gulshan brought her teenage daughter Kareena who was suffering from acute menstrual cramps. Using a diagram of the uterus, the educator explained the basics of menstruation, the importance of hygiene and a nutritious diet, and how to get relief with the help of hot compress and warm drinks. Gulshan left with two packets of Fly pads, the first time she and her daughter will use sanitary napkins.

The Oscar-nominated film was shot in Kathikhera village in 2017. Sulekha, an activist with Action India says, “Everyday a big crowd would come to see the shooting. When they found out it was based on the pad unit, they started talking about the issue. The film partly helped break the silence on periods.”

Later this month, Sneha heads for Los Angeles to attend the Oscar ceremony. “I’m both excited and scared. I haven’t even been to Delhi,” she says. When she saw herself on screen, she felt proud about doing something “hatke”. “It isn’t just about earning money. I want to raise awareness and prove that girls aren’t dependent on anyone, especially husbands,” she says.