Haryana: Sports

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Haryana: Sports

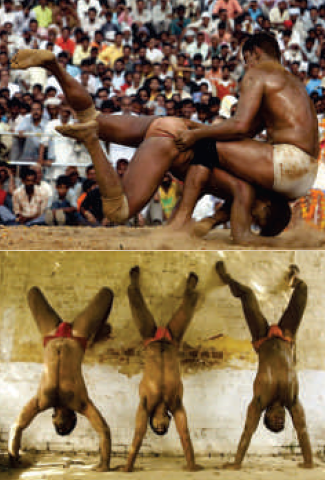

Pahalwans and Wrestlers

Pahalwans and Wrestlers

India Harmony VOLUME - 1 : ISSUE - 5 JULY-AUGUST, 2012

Indian wrestling has come of age in 2012. The glorious wins of Sushil Kumar and Yogeshwar Dutt have certainly put the boys from Haryana on the world stage. However, Kushti (Persian for wrestling) is not new to the soil of Punjab. It is a form of wrestling from South Asia which was developed in the Mughal era. Infact, wrestling or Pehlwani is a synthesis of Indian malla-yuddha and Iranian Varzesh-e Bastani.

Few people know that Kushti or Pehlwani, as known today in India are Persian words for a form of wrestling that was born in Central and South Asia. The precursor of modern Pehlwani an ancient form of wrestling derived from the Vedic texts and was called mallayuddha. Practiced at least since the 5th century BC it is described in the 13th century treatise Malla Purana. From the 12th century India came under the influence of the Mughals, who were of Mongol descent and patronised Persian culture. They brought the influence of Iranian and Mongolian wrestling to the local mallayuddha, thereby creating modern pehlwani.

A practitioner of this sport is referred to as a pehlwan, while teachers are known as ustad (or guru, for Hindu teachers). The undefeated champions of India hold the title Rustam-i-Hind, meaning "the Rustam of India", denoting Rustam the hero of the Iranian national epic, the Shahnameh.

Through time Western training methods and nomenclature from Iran and Europe were introduced into pehlwani. Wrestling competitions, known as dangal, held in Indian villages have their own rules and variations. Usually a win is awarded by decision from the panel of judges.

In the recent past India has produced great wrestlers of world class such as the Great Gama (of British India) and Gobar Goho. India reached its peak of glory in the IV Asian Games (later on called Jakarta Games) in 1962 when all the seven wrestlers were placed on the medal list and between them they won 12 medals in freestyle wrestling and Greco-Roman wrestling. A repetition of this performance was witnessed again when all the 8 wrestlers sent to the Commonwealth Games held at Kingston, Jamaica had the distinction of getting medals for the country. During the 60s, India was ranked among the first eight or nine wrestling nations of the world and hosted the world wrestling championships in New Delhi in 1967.

Pehlwans who compete in wrestling bouts in the present days are also known to cross train in the grappling aspects of judo and jujutsu. Legendary wrestlers from the past like Karl Gotch would tour India to learn the art of pehlwani and further hone their skills. He was gifted a pair of mudgal (exercise equipment used by the Indian wrestlers) during one such visit. The conditioning exercises of pehlwani have been incorporated into many of the conditioning aspects of both catch wrestling and shoot wrestling, along with their derivative systems. These systems also borrow several throws, submissions and takedowns from pehlwani.

In Indian wrestling, vyayam or physical training is meant to build strength and develop muscle bulk and flexibility. Exercises that employ the wrestler's own bodyweight include the Surya Namaskara, shirshasan, and the dand, which are also found in hatha yoga, as well as the bethak. Sawari (from Persian savâri, meaning "the passenger") is the practice of using another person's bodyweight to add resistance to such exercises.

Exercise regimens may also employ the following weight training devices:

The nal is a hollow stone cylinder with a handle inside.

The gar nal (neck weight) is a circular stone ring worn around the neck to add resistance to dands and bethaks.

The gada is a club or mace associated with Hanuman. An exercise gada is a heavy round stone attached to the end of a meter-long bamboo stick. Trophies take the form of gadas made of silver and gold.

Exercise regimens may also include dhakuli which involve twisting rotations, rope climbing, log pulling and running. Massage is regarded an integral part of an Indian wrestler's exercise regimen.

Diet

According to the Samkhya school of philosophy, everything in the universe—including people, activities, and foods—can be sorted into three gunas: sattva (calm/good), rajas (passionate/active), and tamas (dull/lethargic).

As a vigorous activity, wrestling has an inherently rajasic nature, which pehlwans counteract through the consumption of sattvic foods. Milk and ghee are regarded as the most sattvic of foods and, along with almonds, constitute the holy trinity of the pehlwani khurak (from Persian خوراک پهلوانی khorâk-e pahlavâni), or diet. A common snack for pehlwan are chickpeas that have been sprouted overnight in water and seasoned with salt, pepper and lemon; the water in which the chickpeas were sprouted is also regarded as nutritious. The following fruits can also be consumed: apples, wood-apples, bananas, figs, pomegranates, gooseberries, lemons, and watermelons. Orange juice and green vegetables are recommended for their sattvic nature. Most pehlwans avoid eating meat.

Haryana's medal factory

Story : Asit Jolly, India Today, August 17, 2012

Sushil at his home in Baprola.

Kushti mein tukke na laga kare hain (There are no flukes in wrestling)!" Diwan Singh explodes, indignant that anyone could ever insinuate that his son was a "one-win wonder". Olympic silvermedallist Sushil Kumar's father, a driver with Delhi's Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Limited, is thrilled about his son's unprecedented triumph at the London Games, but also a little wistful: "My boy was his best. He was within grabbing distance of the gold medal. Sushil, 29, and his India teammate Yogeshwar Dutt, who won the 60 kg freestyle bronze medal in London, are the biggest success stories from the Chaudhary Devi Lal Sports Centre. The 83-acre Sports Authority of India (SAI) facility-a finishing school for wrestlers-in Sonepat's Bahalgarh village, where India's best hone their grappling skills in gruelling training schedules, has happily been rechristened the 'Haryanvi Medal Factory' by local residents. "Lajawab uplabdhi hai (It's an unparalleled achievement)," says chief coach Anil Khokhar, 35, who has seen a distinct change in younger wrestlers at the centre. From simply striving to participate in international events, he says, "our boys have smelt blood. They all want to chase medals now. Sushil and Yogeshwar have shown them it can be done". Unlike the father, who will just not settle for second spot, the sleepy village of Baprola, on the fringes of Delhi's northwestern border with Haryana, is euphoric about their new hero, Sushil Kumar, silver medallist in wrestling at the London Olympics in the 66 kg freestyle category and a bronze-winner in Beijing in 2008 in the same event. Says Mukhtiar Singh, a veteran of many a past dangal (wrestling tournament), "This boy has made it all worthwhile. His victory makes me feel truly celebrated for the first time in all my 84 years."

Every youngster in Baprola wants to follow Sushil into wrestling. Tenyear-old Ritik and his three friends walked 2 km from their homes to touch the feet of their champion, just back home from London, in keeping with the old akhara tradition. "Kushti ladoge kya (Want to wrestle)?" asks Sushil. All four nod vigorously, swelling visibly with pride. Eighty kilometres to the north along the monsoon-damaged road to Gohana in Haryana's Sonepat district, the residents of Bhainswal Kalan stayed up the night to welcome their own champion. A thousand of them thronged Delhi's Indira Gandhi International Airport to carry the 29-year-old Yogeshwar Dutt home on their shoulders. A large settlement of nearly 20,000 residents, Bhainswal has a long tradition of sending its sons and daughters into teaching. But it's taken the single-minded devotion and grit of a wrestler to bring home the accolades. Pleasantly tidy despite its large population of water buffaloes, every street in the village is paved with concrete and lined with street lamps that actually work. "All this is thanks to Yogeshwar's successes," says Rameshwar Vashishth, 63, a former teacher, recalling how the Bhupinder Singh Hooda government first took note of Bhainswal after the wrestler found a place in the Indian squad for the Beijing Olympics. "Every man, woman and child here owes this young man a debt of gratitude," he says. So they all thronged his freshly repainted house in the centre of the village just before sunrise on August 14 when he drove in. "The first thing he did was to touch the feet of his biggest fan-our mother," says his younger brother Mukesh Dutt, 26. "It rained on the day Yogeshwar was born," says 59-year-old Sushila Devi, fondly hugging her favourite child. "I knew then he was meant for great things. You know how they say sapooton ke paer palaane mein hi pehchaane jaate hain (good sons indicate their path in the crib itself)," she says, quoting an old Haryanvi adage. And breaking a long and worrisome dry spell, there was rain yet again on the morning Yogeshwar returned from London, convincing all in Bhainswal that he is their luckiest charm.

Yogeshwar at his home in Bhainswal.

But besides luck, India's Olympic triumphs are rooted in an age-old rural wrestling tradition that extends all the way from the Najafgarh villages in Delhi to Sonepat, Rohtak, Hisar, Bhiwani in Haryana and further across to Baghpat, Shamli and Meerut in western Uttar Pradesh. It is like a thriving cottage industry. Every other village here has an akhara where older pehalwans (wrestlers) teach youngsters the finer nuances of grappling, widely misconstrued as a rustic sport involving brute strength

"It's all in the soil and water that God gifted our people," says Suresh Malik aka Bhaddal Pehalwan, who trains 100 young boys at the Balraj Akhara, a private wrestling school in Bhainswal Kalan set up over three decades ago by Satbir Singh, a celecelebrated local wrestler. Malik starts them young. His youngest pupils like Harsh, Shivam and Rohit, all between nine and 13 years, fight hard to stay ahead amid the mustard oil and turmeric-infused loam that serves as the mat in their akhara.

"Yogeshwar and I were about the same age and just 30 kg each when we first began training under Mahabali Satpal at Delhi's Chhatrasal Stadium 15 years ago," Sushil recalls. His guru's older brother Chaudhary Dara Singh first spotted the champion, when he won the gold medal at the National School Games in Delhi at the age of 12. "I imagine that (the exhilaration of the school-time victory) is how it would have felt had I struck gold in London," he says a trifle ruefully.

For 17-year-old Praveen Kumar, who just rejoined training at the SAI Centre in Bahalgarh after six months of rehab to treat injuries sustained when miscreants pushed him off a speeding train on his way to his village near Shamli in January, Sushil's silver medal has been inspirational. "Beijing was the beginning but London has shown the world that you cannot mess with Indians," says the youngster who is back to a punishing workout from 4.30 in the morning until lights out at 10.30 p.m. every day.

The results are evident. Fourteen of the 15-man squad of 'Bahalgarh Boys' that participated in the November 2011 Inter-SAI Games at Hisar came back with medals. Six of them struck gold at the national sub-junior wrestling tournament in May 2012.

The 'Haryanvi Medal Factory' is thriving even more with lavish monetary rewards from the state government. Chief Minister Hooda not only announced a cash award of Rs.1 crore for Dutt but went on to proclaim similar prizes for every medallist even remotely connected with his state: Sushil because he speaks Haryanvi and trained here; badminton star Saina Nehwal and shooter Gagan Narang because their families are originally from Haryana

Back in Bhainswal and Baprola, both champions say they are not ready to hang up their boots. "I will go for gold in Rio 2016," says Sushil, who is spending most of his 15-day break before the upcoming SAF Games Camp in September, watching YouTube re-runs of his failed final bout. "I have to spot where I faltered against the Japani (Tatsuhiro Yonemitsu)," he says. Relatively relaxed, Yogeshwar too heads for the computer when he gets the chance.

As Diwan Singh reiterates, "There are no flukes in wrestling. It is all about keeping fit, training hard and perfecting tactics to be far superior to anything your opponent can possibly come up with."

Why Haryana is India’s sports nursery

From: Abhimanyu Mathur, 22 medals at the Commonwealth Games: What makes Haryana India’s sports nursery, April 29, 2018: The Times of India

From: Abhimanyu Mathur, 22 medals at the Commonwealth Games: What makes Haryana India’s sports nursery, April 29, 2018: The Times of India

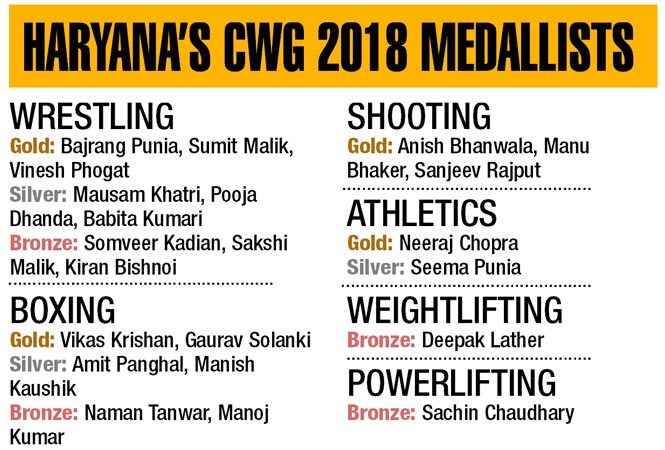

As per the 2011 Census, with just over 2.5 crore people, Haryana’s share in India’s population is a mere 2%. But athletes from Haryana have contributed to one-third of all the medals won by India, including nine out of the 26 golds in CWG. If Haryana was a separate country, it would still be eighth on the 2018 CWG medal tally, behind sporting powerhouses like Australia, England, India, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, and Wales. The episode involving about a dozen of Haryana’s medal-winners from CWG boycotting the state felicitation ceremony over prize money might have soured the post-win festivities a bit, but the fact remains that over the last few years, the state has dethroned its neighbour Punjab as the nursery for Indian sports. Haryana has always been a big contributor in terms of India’s medal haul at major competitions (three of India’s fifteen individual Olympic medals are from the state), but this time, the domination has been unprecedented. Athletes and coaches attribute this domination to a range of factors, including a supportive administration with a concrete sports policy, abundance of idols for youngsters to follow, and greater self-belief in the current crop of athletes.

‘Rural athletes take up sports as winning gives them job security’

The sports policy, which was started by the state government in 2015, was recently amended to include cushier jobs for international medal winners. The new provision in the policy states that Olympic medallists – starting from 2020 – will be given jobs in the Haryana Civil Services (HCS) or Haryana Police Service (HPS). Other states also offer jobs to their medal winners but do not have a set policy on what job is to be awarded. Mostly, such decisions are taken arbitrarily after a win. But jobs in Haryana are not just for those who win medals, but also for the ones with future medal prospects. Kaithal-born boxer Manoj Kumar, who won a bronze in the welterweight category at Gold Coast, says, “People in smaller towns of Haryana are not very financially strong, so they enter sports with the hope of a government job. In other states, jobs are given after an athlete has performed at the national level and won medals, but in Haryana, at least recently, even future medal contenders are identified early on and given jobs. That is how many athletes are able to continue with the sport. Other teams like Services and Railways also scout in Haryana because they know yahan talent hai. Even in Railways, we have more sportspersons from Haryana than any other state now.”

Boxer Manoj Kumar, who won bronze in CWG this year, says that in most states, government jobs are given only after an athlete has won a medal, but in Haryana, even future medal contenders are identified early on and given jobs

‘Emphasis on physical strength gives more boxers and wrestlers’

Traditionally, Haryana has always been a nursery for boxers and wrestlers. It is in these sports of strength that athletes from the state have always won India international acclaim. In Gold Coast too, boxing and wrestling comprised 15 of the 22 medals won by Haryana. Wrestler Sangram Singh says that it stems from the state’s culture that emphasizes physical strength, particularly in the rural areas. “Bete tandarust hone chahiye. We don’t care about whether we have a big house or several cars or not. That is where our physical strength comes from, and that is why Haryana people have excelled in physical sports like wrestling and boxing. Aur ab toh ladke kya, ladkiyan bhi mazboot hoti hain,” the reigning Commonwealth Heavyweight Professional Champion had said last year.

Commonwealth Heavyweight Professional Champion Sangram Singh had said that the reason athletes from Haryana have excelled in boxing and wrestling is that people from the state care the most about their physical strength

‘With more winners, young kids have more idols to follow’

It was after Vijender Singh’s bronze medal at the 2008 Beijing Olympics that an entire generation of youngsters took up boxing in the state. Athletes say that having more champions from the state will make this process spread even faster. Rohtak boxer Amit Panghal, who won silver in light flyweight category at Gold Coast, tells us, “Kehte hain ki Haryana ke khaane mein jaan hai. That is why we have had so many champions in boxing and wrestling from here. And when a lot of people from the state start getting success, the younger lot feels they can do it too. They have idols from their state that they can emulate.”

Rohtak-based boxer Amit Phangal, who bagged silver in light flyweight category at CWG, says that more winners from Haryana means more idols for the kids to emulate

‘Prize money to medallists is the highest in Haryana’

Some former athletes say that what has changed in Haryana is that individual success has given rise to administrative support, chief of which is the highest prize money for winners, which acts as a great incentive for athletes. Arjuna Awardee boxer Akhil Kumar says, “The present crop of athletes and their performances that we see are largely because of the state government’s policies that have been in place for about three-four years now.” The Haryana government’s cash prizes for international medals are easily the highest in the country, which act as a great incentive for athletes. Sample this – an Olympic gold medallist from Haryana gets `6 crore. In comparison, the central government gives `75 lakh for an Olympic gold while the Indian Railways awards such medallists `1 crore. Commonwealth medallists get `1.5 crore, `75 lakh, and `50 lakh for gold, silver, and bronze respectively from the Haryana state government, which is the highest in any state. Tamil Nadu awarded `50 lakh to the 2018 Commonwealth gold medallists, as did Uttar Pradesh. At the other end of the spectrum are Punjab and Delhi, which give their CWG gold medallists `16 lakh and `14 lakh respectively. The prize money for an Asian Games gold given by Haryana is also five times as much as any other state.

Boxer Akhil Kumar says that the performances of the present crop of athletes from Haryana are largely so because of the state government’s policies

‘Haryana’s athletes have greater self-confidence now’

An interesting feature of this year’s CWG haul by Haryana’s athletes was that even as the state did well in the traditionally strong disciplines like boxing and wrestling, new stars emerged in sports the state hasn’t had a rich history in. The record of India’s youngest Commonwealth medallist was broken thrice in these games – all three times by a Haryana athlete. It began in weightlifting, as 18-year-old Deepak Lather from Shadipur won bronze in the 69 kg category. Then, the shooting prodigies took over. Of the three medals won by Haryana in shooting, two were by teenagers – 16-year-old Manu Bhaker from Jhajjar and 15-year-old Anish Bhanwala from Karnal. Former world champion shooter Jaspal Rana, who is currently coaching the Indian junior shooters, says, “In the recent years, Haryana has developed new shooting ranges and that helps because it is a sport that requires investment.” Apart from shooting, Haryana also struck gold on the track and field as 22-year-old Panipat boy Neeraj Chopra won a gold in javelin throw. Gurgaon-based athletics coach Raj Yadav, says, “There is greater belief in Haryana’s kids now. Having seen boxers and wrestlers succeed, the track and field athletes believe they can win too now. And that belief in self is important in big competitions if you want to win. That talent was always there, but now, players are more confident.” However, with the Asian Games in August and the Olympics less than two years away, tougher challenges lie ahead for Haryana’s Commonwealth champions. If Gold Coast is anything to go by, the nation will certainly be looking at Haryanvi boys and girls to add weight to India’s medal tallies at the major international sporting competitions in the years to come.

Former world champion shooter Jaspal Rana, who is currently coaching Indian junior shooters, says that Haryana has also developed new shooting ranges, as part of making way for people to take up sports different from the traditionally strong disciplines like boxing or wrestling

Haryana’s contribution to India’s medal tallies

2018: Commonwealth Games

Hindol Basu, April 17, 2018: The Times of India

Had Haryana been a nation, it would have ranked 8th in 2018 CWG Chandigarh:

Had Haryana been a country, it would have ranked 8th in the CWG medals table – above Olympic nations like Scotland, Jamaica, Nigeria and Malaysia. Out of the 66 medals that India won, Haryana boys and girls won 22. They bagged 10 gold, 6 silver and 6 bronze in Gold Coast. Besides India’s tally, Australia, England, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and Wales are above Haryana’s count.

2008- 2020; 2024 (partial)

August 4, 2024: The Times of India

From: Hindol Basu, August 3, 2024: The Times of India

It’s 5.30am and runners outnumber cars on the highway that connects Rohtak and Bhiwani. They are completing a cross-country run across fields and through woods. Not all of them are track and field athletes. The group has boxers, wrestlers and shooters. It’s a Saturday ritual for them. Get up at 3.30. Begin the cross-country by 4, complete it by 7, and head for the academy. Running, lifting, flexing — across districts and academies, this is how mornings begin in village after village in Haryana, the engine room of India’s sporting successes beyond cricket.

Blessed with a sporting temper and an athletic predisposition, which also fuels its other passion — the armed forces — the state with 2% of India’s population accounts for 30% of all Olympic medals the country has won and 21% of India’s Paris Olympics contingent.

“It’s the sports culture in Haryana that is producing so many Olympians. There is something special about the soil here,” Neeraj Chopra, gold medallist at Tokyo Olympics, had earlier told this reporter. Chopra is from Haryana. As is the poster girl of India’s Paris Games success, Manu Bhaker.

There are, says wrestling coach Ashok Dhaka, also strong dietary and cultural reasons for Haryana being a sporting powerhouse. “Doodh dahi ka khana, sabse aagey Haryana. Our diet is rich in milk, ghee, curd, butter and paneer, which supports physical development required for hard physical activity, whether getting into sports or joining the forces or working in farms,” he says. “Emphasis on good nutrition, regular exercise at school grounds or village akhadas, and participation in competitive sports has been part of Haryanvi culture,” Dhaka, who runs the famed Bhagat Singh Akhada in Rohtak, adds.

Just Naturally Tough

Of India’s 117-member Paris contingent, 24 are from Haryana and 19 from Punjab. In the 2020 Tokyo Games, Haryana had 31 athletes and Punjab 19 in the 119-member contingent. This time, Haryana athletes are participating in eight disciplines – archery, athletics, boxing, golf, hockey, rowing, shooting and wrestling. Pun- jab athletes are contesting in four disciplines — athletics, golf, hockey and shooting. Tamil Nadu is third in terms of representation with12 athletes. “The Green Revolution in the 1970s made Punjab and Haryana the top crop producers in the country. People must perform extreme physical labour to grow crops. Hence, they are generally stronger and fitter,” says Jagdish Singh, coach and founder of the famed Bhiwani Boxing Club (BBC), which has churned out celebrated Olympians like Vijender Singh, Akhil Kumar, Vikas Krishan and Dinesh Kumar.

In Haryana, most households own small landholdings, but families cannot afford to hire labour. So, family members — male or female — undertake agricultural work themselves. “We are rough and tough. We fought battles against Mughals and the British. That mental as well as physical toughness has been passed down generations. It’s in our genes,” says Ranbir Dhaka, coach at the Guru Mehar Singh Akhada in Rohtak.

Haryana, and Punjab have always been major contributors to the Army. Sports is second nature. And the two often converge. Legendary athletes like Milkha Singh and Balbir Singh Sr and heavyweight boxer Capt Hawa Singh served in the armed forces. Neeraj is a JCO in the Army.

“I want to join the Army,” says Aryan Malik, a 110m hurdler who trains at Shiva ji Stadium in Panipat, the place where Neeraj Chopra learned to throw a javelin. “Army has the kind of setup that is needed to train world-class athletes. I don’t have to worry about my diet. I can just focus on developing my skills,” says the 18-year-old. “There will be incentives and benefits. It will be a secure job with regular promotions. Everything will be taken care of,” says fellow athlete Naveen.

Dhoni Doesn’t Mean Cricket

In most of India, a boy named after MS Dhoni is likely to play only one game. But tanned and breathless from his cross-country run, 12-year-old Dhoni is headed for ‘kushti’ lessons at Bhagat Singh Akhada near the Indian Institute of Man- agement campus in Rohtak.

Like many young wrestlers, Dhoni landed up at the ‘akhada’ because it would take care of both his education and vocation. The residential academy – with 80 young wrestlers, several of them medalwinners at international championships – is now his home. “One of my students defeated Bajrang Punia at the trials recently,” says Ashok Dhaka, who runs the akhada. Punia, a decorated wrestler, won bronze at the Tokyo Olympics.

“They’re hungry for recognition,” Ashok Dhaka sums up the motivating factor that makes these youngsters stick to a sport that doesn’t have the glamour or money of cricket. “The recognition one gets after winning an Olympic medal or a Commonwealth or Asiad medal is unparalleled. They have seen wrestlers from Haryana become international stars. They have that burning desire to do the same,” adds Dhaka, who is the nephew of Dronacharya award-winning wrestling coach Capt. Chand Roop. The Chandroop Akhada in Delhi is in his name and is run by the family.

Akhadas aren’t just about learning the intricate knots of ‘kushti’ but also life lessons like the ‘gurushishya’ relationship. Before getting into the mud pit, where Indian pehalwans are groomed before they move to the mat, Dhoni must do the ceremonial knee-touching of his ‘guruji’, who instructs him to have munakka (black grape raisin) juice and then help others level the pit for ‘kushti’. “Respect for the guru is paramount in wrestling and it’s a tradition still prevalent in our state. That’s why we win so many medals at the international level,” says Dhaka.

Track & Field Pull

After Neeraj’s Olympic gold in Tokyo, the number of kids interested in javelin throw and other track and field events has shot up.

Cast your eye wide at Panipat’s Shiva ji Stadium and you will see hundreds of kids practising shot put, discus throw, javelin, sprint and distance running. “Our intake for track and field events has increased dramatically. I can safely say, by the thousands. See what one medal can do,” says coach Mahipal Gaur, who trained at the National Institute of Sports, Patiala. He presides over the sessions at the Panipat stadium. Another sport that has seen a more recent surge in interest is shooting, traditionally a Punjab stronghold, which got a major fillip after Abhinav Bindra’s gold at the 2008 Beijing Games. Manu’s twin bronze medals will likely do the same for the sport in Haryana.

“The number of shooting ranges has gone up across the state, but especially in Faridabad. There are dozens of shooting ranges in the city and 25-30 players competing at the national level from each range. It just shows what is possible if infrastructure is there,” says shooting coach Rakesh Thakur.

Assured Job, Big Cash

Owned and managed by Haryana govt, Shiva ji Stadium is among several top-notch academies and training facilities that Haryana govt has developed. The state has backed that up with financial incentives, jobs in the public sector for athletes and funding for training facilities.

In 2000, when Om Parkash Chautala was CM, the state announced for the first time that it would give cash rewards of Rs 1 crore to each Olympic medallist. The announcement created a buzz. The Bhupinder Singh Hooda govt took this a step further with Haryana Sports Policy, 2006, making support to sports and sportspersons structural and systemic. It linked sporting achievements not just to cash incentives but also employment in the form of high level govt jobs. The slogan was ‘padak lao, pad pao (bring a medal, get a job)’. Added focus was put on building modern training centres and wrestling and boxing academies. The assurance of financial and job security made a big difference.

“Cash incentives and job security are a major reason behind Haryana’s success at the international level. In rural areas, a sportsperson commands huge respect and that motivates others to join sports,” says Bhim Chopra, Neeraj’s uncle. The current govt has continued with the policy and, in fact, enhanced the cash reward — Rs 6 crore for an Olympic gold medallist, Rs 4 crore for a silver medallist and Rs 2.5 crore for a bronze medallist is the highest in the country. The Centre gives Rs 75 lakh to an Olympic gold winner, Rs 50 lakh for silver and Rs 30 lakh for bronze.

The Haryana 2016-17 sports policy emphasises the ‘right to fitness and right to play’ for everyone and lists ambitious plans like building a mini stadium in each gram panchayat.

Players are given job offer letters along with an offer to receive an HSVP (Haryana Shahari Vikas Pradhikaran) plot at a concessional rate. Even a fourth-place finish at the Olympics gets an athlete Rs 50 lakh from the state govt. Qualification is also acknowledged, with a Rs 15 lakh cash reward and job offer letters.

“Many of the athletes come from poor backgrounds. They go through a lot of struggle to get medals. Cash rewards and govt jobs act as an assurance. They can fully concentrate on training without worrying about providing for their families. Sports works as a vehicle to a better life, a gateway to a govt job and secure future,” says Jasveer Ahlawat, a former international boxer and currently a coach at Rajiv Gandhi Sports Complex in Rohtak.

Winning Gender Battle Too

“Mhaari chhoriyaan chhoron se kam hai ke (Are my daughters less capable than the boys?)” That’s Mahavir Phogat, played by Aamir Khan in the Bollywood movie ‘Dangal’, talking about his daughters Geeta and Babita. Haryana, infamous for female infanticide, still has a skewed sex ratio, but what has been consistently changing after Geeta and Babita Phogat’s gold medals at the Commonwealth Games (2010 and 2014) is parents’ attitude towards their daughters taking up sports. The big moment came in 2016 when Sakshi Malik won bronze at the Rio Olympics, the first Indian woman wrestler to win an Olympic medal. “Families have become more supportive,” says middleweight boxer Pooja Rani, an Asian Games bronze medallist. “Also, women have more autonomy now (to decide what they want to do),” she adds.

At Paris Olympics, of the 24 athletes from Haryana, 14 are women. All six members of the Indian wrestling team are from Haryana. Five of them women. “Women have broken barriers and won laurels for India. Sports has become a medium for us to show what we are capable of,” Pooja says.