Hazaribagh district

Contents |

Hazaribagh District in 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

North-eastern District in the Chota Nagpur

Division of Bengal, lying between 23° 25 and 24° 49' N. and 84° 27'

and 86° 34 E., with an area of 7,021 square miles. It is bounded on

The north by the Districts of Gaya and Monghyr ; on the east by the

Santal Parganas and Manbhum ; on the south by Ranch!; and on the

w(jst by Palamau.

Physical aspects

Hazaribagh, which, like the rest of Chota Nagpur, consists to a great extent of rock and ravine, lies towards the north-eastern extremity of the chain of high land, sometimes a range of hills and sometimes a cultivated plateau, which extends across asoects the continent of India south of the Narbada river on the west and of the Son river on the east. It is divided naturally into three distinct tracts : an undulating plateau, with an average elevation of about 2,000 feet, extends from the west-central boundary of the District, measuring about 40 miles in length from east to west and 15 miles from north to south; a lower and more extensive plateau, with a general elevation of 1,300 feet, covers the north and cast of the District, gradually sinking towards the east; while the central valley of the Damodar river, with the country watered by its numerous feeders, occupies the entire south of the District.

The principal peaks of the southern plateau are Baragai or Marang Buru (3,445 feet above the sea), Jilinga (3,057 feet), Chendwar (2,816 feet), and Aswa (2,463 feet). Detached hills are Lugu (3,203 feet), Mahudi (2,437 ^^et), and in the east of the District, on the boundary of Manbhum, the well- known Parasnath Hill, 4,480 feet above the sea. In the northern plateau is the Mahabar range, rising to an elevation of 2,210 feet above sea-level. The Damodar, which rises in Palamau, is the most important river of Hazaribagh, through which it flows in an easterly direction for about 90 miles.

Its chief feeders in this portion of its course are the Garhi, Haharo, Naikari, Maramarha, Bhera, Kunur, Khanjo, and Jamunia, and with its tributaries it drains in this District an area of 2,840 square miles ; it is everywhere fordable during the dry season. The only other important river, the Barakar, rises on the northern face of the central plateau and flows in an easterly and south- easterly direction till, after draining an area of 2,050 square miles, it leaves the District to form the boundary between Manbhum and the Santal Parganas. The north-west of the District is drained by the Jhikia and Chako, which unite a short distance outside the boundary; by the Mohani, Lilajan, and Morhar, which flow northwards into Gaya ; and by the Dhadhar, Tilaya, and Sakri. The Ajay rises on the eastern boundary of the District, two of its tributaries draining part of the Giridlh subdivision, while on the south the Subarnarekha forms the District boundary for about 15 miles.

A description of the geology of Hazaribagh District would practically be a summary of the characters of any Archaean area. The old felspathic gneisses, well banded and with the composition of typical igneous rocks, are associated with schistose forms and with the results of the intermingling of ancient sediments with igneous matter. Among these are intrusive masses of granite which, under pressure, have assumed a gneissose structure and, on account of the way in which they stand up as small hills of rounded hummocks, have sometimes been referred to as the 'dome gneiss.' They rise u[) in the midst of bands of schists, which are cut in all directions by veins of acid pegmatite. Patches of Gondwana rocks occur, some of which contain the coal for which the District is well-known ^

The narrower valleys are often terraced for rice cultivation, and these rice-fields and their margins abound in marsh and water plants. The surface of the plateau between the valleys, where level, is often bare and rocky, but where undulating is usually clothed with a dense scrub jungle in which Dendrocalamus strictus is prominent. The steep slopes of the ghats are covered with a dense forest mixed with many climbers. Sal {Shorea robusla) is gregarious ; among the other noteworthy trees are species of Buchana7ua, Semecarpus, Teriuinalia, Cedtr/a, Cassia,

' ' The Mica Deposits of India,' by Holland, in Memoirs, Geological Survey of fmiia, vol. xxxiv, part ii (1902) ; ' The Igneous Rocks of Glrldih and their Contact Effects,' by Holland and Saise, in Records, Geological Survey of India, vol. xxviii, part iv (1S95). Butea, Baiihinia^ Acacia, Adina, which these forests share with the similar forests on the Lower Himalayan slopes. Mixed with these, however, are a number of characteristically Central India trees and shrubs, such as Cochiosperfnum, Soymida, BoswelUa, Hardzvickia, and Bassia, which do not cross the Gangetic plain. One of the features of the upper edge of the g/idfs is a dwarf palm. Phoenix acaulis ; striking too is the wealth of scarlet blossom in the hot season produced by the abundance of Butea frondosa and B. superba, and the mass of white flower along the ghats in November displayed by the convol- vulaceous climber Porana panicu/ata.

The jungles in the less cultivated tracts give shelter to tigers, leopards, bears, and several varieties of deer. Wolves are very com- mon, and wild dogs hunt in packs on Parasnath Hill.

The temperature is moderate except during the hot months of April, May, and June, when westerly winds from Central India cause high temperature with very low humidity. The mean temperature increases from 76° in March to 85° in April and May, the mean maximum from 89° in March to 99° in May, and the mean minimum from 64° to 76°. During these months humidity is lower in Chota Nagpur than in any other part of Bengal, falling in Hazaribagh to 41 per cent, in March and 36 per cent, in April. In the winter season the mean temperature is 60° and the mean minimum 51°. The annual rainfall averages 53 inches, of which 7-6 inches fall in June, i4'4 in July, 13-4 in August, and 8-5 in September.

History

The whole of the Chota Nagpur plateau was known in early history as Jharkand or 'the forest tract,' and appears never to have been completely subjugated by the Muhammadans. Santal tradition relates that one of their earliest settlements was at Chhai ( 'hampa in Hazaribagh, and that their fort was taken by Saiyid Ibrahim All, a general of Muhammad bin Tughlak, and placed in charge of a Muhammadan officer, ^;m? 1340. There is no authentic record, however, of any invasion of the country till Akbar's reign, when it was overrun by his general. The Raja of Chota Nagpur l)ecamc a tributary of the Mughal government (1585) ; and in the Ain-i-Akbarl Chhai Champa is shown as a pargaiia belonging to Bihar assessed at Rs. 15,500, and liable to furnish 20 horse and 600 foot. Subse- (lucntly, in 1616, the Raja fell into arrears of tribute; the governor of Bihar invaded his country ; and the Raja was captured and removed to Gwalior.

He was released after twelve years on agreeing to pay a yearly tribute of Rs. 6,000, and his country was considered part of the Siibah of Bihar. I'^rom the fact that the ancestor of the Rajas of Ramgarh (which included the present District of Hazaribagh) is said to have received a grant of the estate from these Nagbansi Rajas, it appears that the District formed part of their dominions. The inroads of the Muhammadans were, however, directed not against the frontier chiefdom of Ramgarh but against Kokrah, or Chota Nagpur proper, to which they were attracted by the diamonds found in its rivers ; and though the Rajas were reduced to the condition of tribu- taries by the Mughal viceroys of Bengal, they were little interfered with so long as their contributions were paid regularly. Even so late as the reign of Aurangzeb the allegiance of the chiefs of this tract must have been very loose, as the Jharkand route to Bengal is said to have been little used by troops on account of the savage manners of the moun- taineers. About this time the first Raja of Kunda, who was a personal servant of the emperor, received a rent-free grant of the pargana on condition that he guarded four passes from the inroads of Marathas, Bargis, and Pindaris ; and in 1765 Chota Nagpur was ceded to the British as part of Bihar. The British first came into contact with this tract in 1771, when they intervened in a dispute between one Mukund Singh, the Raja of Ramgarh, and his relative Tej Singh, who was at the head of the local army. The latter, who had claims to the estate, went in 1771 to Patna and laid his case before Captain Camac, who undertook to assist him and deputed for the purpose a European force under Lieutenant Goddard. Mukund Singh fled after a mere show of resistance, and the Ramgarh estate was made over to Tej Singh subject to a tribute of Rs. 40,000 a year. Lieutenant Goddard's expedition did not extend to the Kharakdlh pargana in the north- west of the District. Six years earlier (1765) Mad Narayan Deo, the old Hindu Raja of Kharakdlh, chief of the ghahvdls or guardians of the passes, had been driven from his estate by the Musalman dmil or revenue agent, Kamdar Khan, who was succeeded by Ikbal AH Khan. The latter was expelled in 1774 for tyranny and mismanage- ment by a British force under Captain James Brown. The exiled Raja of Kharakdlh, who had exerted his influence on the British side, was rewarded with a grant of the maintenance lands of the Raj. Possibly he might have been completely reinstated in his former position ; but in the confusion of Muhammadan misrule the ghdtwdh had grown too strong to return to their old allegiance, and demanded and obtained separate settlements for the lands under their control. In the sanads granted to them by Captain Brown they are recognized as petty feudal chiefs, holding their lands subject to responsibility for crime committed on their estates. They were bound to produce criminals, and to refund stolen property ; they were liable to removal for misconduct, and they undertook to maintain a body of police, and to keep the roads in repair.

In 1780 Ramgarh and Kharakdlh formed part of a British District named Ramgarh, administered by a Civilian, who held the offices of Judge, Magistrate, and Collector ; while a contingent of Native infantry, known as the Ramgarh battalion, was stationed at Hazaribagh, under the command of a European officer. This District was dis- membered after the Kol insurrection of 183 1-2, when under Regulation XIII of 1833 parts of it were transferred to the surrounding Districts, and the remainder, including the parganas of Kharakdlh, Kendi, and Kunda, with the large estate of Ramgarh, consisting of 16 /xirgatias, which compose the present area of the District, were formed into a District under the name of Hazaribagh. In 1854 the title of the officer in charge of the District was changed from Principal Assistant to the Governor-General's Agent to Deputy-Commissioner.

The most important archaeological remains are the Jain temples at Parasnath. Buddhist and Jain remains exist on Kuluha Hill in the Dantara pargajia, and a temple and tank to the west of the hill dedicated to Kuleswari, the goddess of the hill, are visited by Hindu pilgrims in considerable numbers. The only other remains worthy of mention are four rock temples on Mahudi Hill, one of which bears the date 1740 Samvat, ruins of temples at Satgawan, and an old fort which occupies a strong defensive position at Kunda.

Population

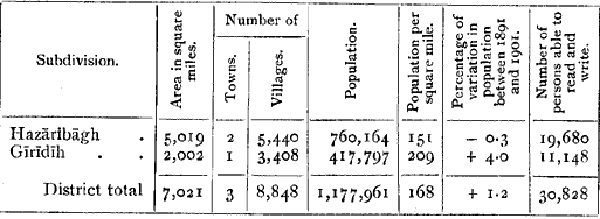

At the Census of 1872 the population recorded in the present District area was 771,875. The enumeration was, however, defective; and the Census of 1881 showed a population of 1,104,742, which rose to 1,164,321 in 1891 and to 1,1 77,961 in 1 901. The smallness of the increase during the last decade is attributable to the growing volume of emigration to Assam and else- where, and also to the heavy death-rate following the famine of 1897, chiefly from fever and cholera, which are always the most prevalent causes of mortality in the District. The principal statistics of the Census of 1901 are shown below : —

The three towns are Hazaribagh, the head-quarters, Chatra, and GiRiDiH. The population is greatest in the west, in the valley of the Barakar river, where there is a fair extent (jf level country and the coal mines support a considerable number of labourers. The country west and south-west of the central plateau consists mainly of hill and ravine, and has very few inhabitants. The population declined during the decade ending 1901 in the centre of the District, where recruiting for tea gardens was most active ; but in the Giridili subdivision there was a general increase, the growth being most marked in Girldih itself, where the coal-mines of the East Indian railway attract a steadily increasing number of labourers. The hardy aboriginal tribes are remarkable for their fecundity and the climate is healthy ; but the soil is barren, and the natural increase in the population is thus to a great extent discounted by emigration. It was hence that the Santals sallied forth about seventy years ago to people the Daman-i-koh in the Santal Parganas. This movement in its original magnitude has long since died out, and the main stream of present emigration is to more distant places, Assam alone containing nearly 69,000 natives of this District. The Magahi dialect of Biharl is spoken by the majority of the popula- tion, but Santall is the vernacular of 78,000 persons. Hindus number 954,105, or 81 per cent, of the total, and Muhammadans 119,656, or 10 per cent.

Agriculture

The most numerous Hindu castes are Ahirs or Goalas (138,000) and Bhuiyas {99,000) ; many of the Bihar castes are also well repre- sented, especially Kurmis (76,000), Telis (49,000), Koiris (47,000), and Chamars (44,000), while among other castes Ghatwals (40,000), Bhogtas (35,000), and Turis (23,000) are more common than elsewhere, and Sokiars (12,000) are peculiar to the District. Most of the Animists are Santals (78,000), and the majority of the Musalmans are Jolahas (82,000). Agriculture supports 80-7 per cent, of the population, industries 9-1 per cent., commerce 0-2 per cent., and the professions 0'8 per cent.

Of 1,163 Christians in 1901 about three-fourths were natives. Mission work was begun in 1853 by the German Evangelical Lutheran Mission, but was interrupted by the Mutiny. In 1862 another mission was founded by the same society at Singhani near Hazaribagh ; but in 1868 an unfortunate split took place, and several of the missionaries went over to the English Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. The work carried on by the German mission is chiefly educational. The Free Church of Scotland opened a branch of its Santal Mission at Pachamba near Glridlh in 187 1, and maintains a dispensary and schools ; their evangelistic work is chiefly among the Santals. The Dublin University Mission, established at Hazaribagh in 1892, main- tains a boys' high school, an upper primary school, and a First Arts college, in addition to dispensaries at Hazaribagh, Ichak, and Petiirbar; but it has not been very successful in making conversions.

The most fertile land lies in the valleys of the Damodar and the Sakri, the agricultural products of the latter resembling those of the adjoining Districts of Bihar rather than those of the neighbouring parts of Chota Nagpur. In Kiiarakdih the hollows that lie between the undulations of the surface are full of rich alluvial soil, and present great facilities for irrigation ; but the crests of the ridges are, as a rule, very poor, being made up of sterile gravel lying on a hard subsoil. In Ramgarh the subsoil is light and open, and the surface is composed of a good ferruginous loam, while many of the low hills are coated with a rich dark vegetable mould. The beds of streams are frequently banked up and made into one long narrow rice-field. For other crops than rice the soil receives practically no preparation beyond ploughing. Failures of the crops are due to bad distribution of the rainfall, never to its complete failure; the soil does not retain water for long, and a break of ten days without rain is sufficient to harm the rice crop.

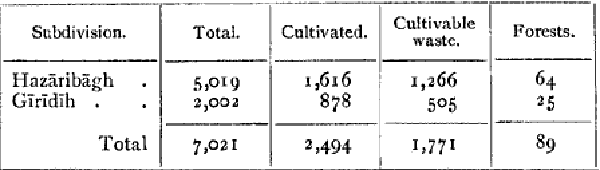

The agricultural statistics for 1903-4 are shown below, areas being in square miles : —

Rice is the most important crop. Gord or early rice is sown broad-

cast after the first fall of rain in June, and is reaped about the end

of August. Aghani or winter rice is sown in June, and reaped in

November or December ; it is either sown broadcast or transplanted.

After rice by far the most important crops are maize and iiianni.

Other food-grains are go/idIi\ i/rd, barai, rahar, kurthl, gram, wheat,

barley^ and khesdri \ of other food-crops the most important are sugar-

cane, mahiid, and various vegetables. Oilseeds are extensively grown,

consisting chiefly of sarguja, til^ rape-seed, and linseed, while among

other products may be mentioned poppy, cotton, and renii, a jungle

root used for the manufacture oi pachwai. A little tea is still grown,

but the industry is rapidly dying out; in 1903-4 there was only one

tea garden, which had an output of 3,700 lb.

The area under cultivation is gradually being extended by terracing the slopes and embanking the hollows, and by bringing under the plough the tops of ridges. The people have no idea of adopting improved agricultural methods, though they are willing to make use of seed given to them, and cultivators near Hazaribagh and Giridih are beginning to grow English vegetables, such as cauliflowers and tomatoes. Loans amounting to Rs. 51,000 were given during the famine of 1897, and Rs. 29,000 was advanced in 1900-1 under the Agriculturists' Loans Act in consequence of a failure of the cxo\)^. Little advantage has been taken of the Land Lnprovement Loans Act.

'I'he breed of cattle is poor. The cattle are ordinarily grazed in the jungles ; land is set apart for pasture in villages in which there is no jungle, but the grass is poor, and the cattle get no proper fodder except just after harvest.

The average irrigated area is estimated at 393 square miles. Irriga- tion is carried on by means of bdndhs and dhars, as described in the article on Gay.\ District. Well-water is used only for the poppy.

Forests

Hazaribagh contains 56 square miles of 'reserved,' and 33 square miles of ' protected ' forest. The Kodarma Reserve, which is the most important forest tract, covers 46 square miles on the scarp of the lower plateau, the elevation varying from about 1,200 feet near Kodarma to about 500 feet on the Gaya boundary. The predominant tree is sd/ {Shorea robi/sia), but there are few trees of any size, most of the larger ones having been cut out before the forest was constituted a Reserve in 1880. Bamboos are scattered throughout the Reserve ; and the other principal trees are species of Temiinalia, Bauhinia, and Ficus, Bass/a latifolia, Storulia i/rens, Cassia Fistula^ Mangifera indica, Semecarpiis A?iacardiitm, Biitea frondosa, Lagerstroe- mia parviflora, Woodfordia floribunda^ Eugenia Jambolana, and Phoenix acaidis. The minor products are thatching-grass, sabai grass {Ischae- mum angusiifo/ium), mahi/d flowers {Bassia /afifo/ia), and myrabolams ; but none of these is at present of any great importance on account of the distance of the forest from the railway. Owing to excessive grazing and cutting, the ' protected ' forests contain no timber of any size. In 1903-4 the total forest revenue was Rs. 14,500, of which Rs. 10,000 was derived from the rent for mica mines.

Minerals

From the veins of pegmatite in the gneiss is obtained the mica which has made Hazaribagh famous. The pegmatites have the composition of ordinary granite, but the crystals have been deve- loped on such a gigantic scale that the different mine- rals are easily separable. Besides the mica, quartz, and felspar, which form the bulk of the pegmatite, other minerals of interest, and some- times of value, are found. Beryl, for instance, is found in large crystals several inches thick ; schorl occurs in nearly all the veins ; also cas- siterite (tin-stone), blue and green tourmaline. Lepidolite and fluor- spar occur near Manimundar (24° 37' N., 85° 52' E.) ; columbite. which includes the rare earths tantalum and niobium, exists in one or two places ; and apatite, a phosphate of lime, is found in the Lakamandwa mica mine near Kodarma.

Mica in the form of muscovite is the only mineral which has been extracted for commercial purposes. It is worked along a belt which runs from the corner of Gaya District across the northern part of Hazaribagh into Monghyr. Along this belt about 250 mines have been opened. With the exception of Bendi, which is being tested by means of systematic driving and sinking, these are all worked by native methods. The ' books ' of mica are of various sizes up to 24 by 18 by 10 inches, the more common being about 8 by 4 by 3 inches. The usual practice is to prospect the surface in the rains for these

- books ' or indications of them, and then work the shoots or patches

during the dry season. The pumping and winding are done by hand. The total output from 238 mines worked in Hazaribagh in 1903 was 553 tons, valued at 9^ lakhs. The average number of persons employed daily was 5,878, the average daily wages being for a man 2\ to 4^ annas, for a woman 2 annas, and for a child i to i^ annas.

The deposit of cassiterite takes a bedded form conformable to the foliation planes of the gneisses and schists in the neighbourhood of Naranga (24° 10' N., 86° 1' E.) in the Palganj estate, 10 miles west of the Giridlh coal-field. Unsuccessful attempts were made to work this deposit by a company which ceased operations in 1893, after having carried down an inclined shaft for over 600 feet along the bed of ore. Cassiterite has also occasionally been obtained in mistake for iron ore in washing river sands, and the native iron-smelters have thus obtained tin with iron in their smelting operations. Lead, in the form of a dark red carbonate, has been found at Barhamasia (24° 20' N., 86° 18' E.) in the north of the District. Similar material has been found in the soil at Mehandadih (24° 22' N., 86° 20' E.), Khesmi (24° 25' N., 84° 46' E.), and Nawada (24° 25' N., 84° 45' E.). Argenti- ferous galena, associated with copper ores and zinc blende, occurs on the Patro river, a mile north-north-east of Gulgo. An unsuccessful attempt was made in 1880 to work these ores.

The sulphide of lead, galena, has also been obtained in connexion with the copper-ore deposits of Baraganda. A deposit, which has been known since the days of Warren Hastings and has been the subject of many subsequent investigations, occurs near Hisatu (23° 59' N., 85° 3' E.); an analysis of the ore made by Piddington showed the presence of antimony with the lead. The most noteworthy example of copper ores occurs at Baraganda in the Palganj estate, 24 miles south-west of (iTridlh. In this area the lead and zinc ores are mixed with copper pyrites, forming a thick lode of low-grade ore which is interbedded with the vertical schists. Shafts reaching a depth of 330 feet were put down to work this lode by a company which commenced operations in 1882, but apparently through faulty management the undertaking was not suc- cessful and closed for want of funds in 1891.

Lobars and Kols formerly smelted iron in this District, but owing to forest restrictions and the competition of imported English iron and steel, the industry has practically died out. The ore used was principally magnetite derived from the crystalline rocks. Hematite, how- ever, is also obtained from the Barakar stage of the Cionthvana rocks of the Karanpura field, and clay ironstone occurs in a higher stage of the Damodar series in the same area.

The most conspicuously successful among the attempts to develop the mineral resources is in a little coal-field near Girldlh. The small patch of Gondvvana rocks, which includes the coal in this field, covers an area of only 1 1 square miles, and includes 3^ square miles of the Talcher series, developed in typical form with boulder-beds and needle- shales, underlying sandstones whose age corresponds with the Barakar stage of the Damodar series. The most valuable seam is the Karhar- bari lower seam, which is seldom less than 1 2 feet in thickness and is uniform in quality, producing the best steam coal raised in India, more than two-thirds of it consisting of fixed carbon. This seam persists over an area of 7 square miles, and has been estimated to contain 113,000,000 tons of coal. The Karharbari upper seam is also a good coal, though thinner ; and above it lie other seams, of which the Bhaddoah main seam was at one time extensively worked. The total coal resources of this field are probably not less than 124,000,000 tons, of which over 15,000,000 have been raised or destroyed. Like practi- cally all the coal-fields of Bengal, the Gondwana rocks of Giridih are pierced by two classes of trap dikes : thick dikes of basaltic rock, which are probably fissures filled at the time at which the Rajmahal lava-flows were poured out in Upper Gondwana times ; and thin dikes and sheets of a peculiar form of peridotite, remarkable for containing a high percentage of apatite, a phosphate of lime. This rock has done an amount of damage among the coals which cannot easily be estimated, as besides cutting across the coal seams in narrow dikes and coking about its own thickness of coal in both directions, it spreads out occasionally as sheets and ruins the whole or a large section of the seam over considerable areas.

In this field 9 mines employed in 1903 a daily average of 10,691 hands and had an output of 767,000 tons. The East Indian Railway Company, by whom the bulk of the coal in this field is raised, work it for their own consumption, and have invested 15 lakhs in their mines.

The miners are of various castes ; but Santals and the lower castes of Hindus, such as Bhuiyas, Mahlis, Ghatwals, Chamars, Dosadhs, and Rajwars, predominate. The daily wages paid in the mines worked by the East Indian Railway Company are : for coal-cutters, 6 to 8 annas ; horse-drivers underground, 4 annas ; women (underground), 3 to 4 annas ; fitters, 8 annas to R. 1-8-0 ; and for coolies working above ground, men, 2\ annas to 4 annas; women, i^ to 2 annas; and children, i^ to i^ annas. One shaft, the deepest in India, has a depth of 640 feet, and nearly all the coal is wound by modern plant.

This is the only field in the District which is regularly worked, but other patches of Gondwana rocks are also coal-bearing. A patch near the village of Itkhori, 25 miles north-west of Hazaribagh, includes about half a square mile of the Barakar stage lying on a considerable area of Talchers. There are three seams containing possibly about 2,000,000 tons of inferior coal. The Bokaro and Karanpura fields lie in the low ground of the Damodar river, at the foot of the south- ern scarp of the Hazaribagh plateau. The Bokaro field commences 2 miles west of the Jherria field, and is likely to become important with farther railway extensions. It covers 220 square miles and includes coal seams of large size, one of 88 feet thick being measured. The coal resources of this field are estimated to aggregate 1,500,000,000 tons. In the Karanpura area a smaller tract of 72 square miles has been separated from the northern field of 472 square miles through the exposure of the underlying crystalline rocks. There is a large quantity of fuel available in these two fields ; in the smaller there must be at least 75,000,000 tons and in the northern 8,750,000,000. In The Ramgarh coal-field to the south of the Bokaro field the rocks are so faulted that it may not be profitable to mine the coal

Trade and Communication

Cotton-weaving is carried on by the Jolahas, but only the coarsest cloth is turned out. A few cheap wooden toys are made by Kharadis, and blankets by Gareris, while agricultural imple- Trade and ments and cooking utensils are manufactured from communications, locally smelted iron ore.

The chief imports are food-grains, salt, kerosene oil, cotton twist and European cotton piece-goods ; and the chief exports are coal and coke. Of the food-grains, which form the bulk of the imports, rice comes chiefly from Manbhiim, Burdwan, and the Santal Parganas, wheat from the Punjab and the United Provinces, and gram from Monghyr and Patna ; the other imports come from Calcutta. The coal and coke exported by rail in 1903-4 amounted to 495,000 tons, of which 86,000 tons went to Calcutta, 195,000 tons to other parts of Bengal, 114,000 tons to the United Provinces, and the remainder to the Punjab, Central Provinces, Rajputnna, and Central India. Minor exports are mica, catechu, sabai grass, lac, mahud, and hides. Hazari- bagh, Glrldih, and Chatra are the y)rincipal marts, and form the centres from which imported goods are distributed by petty traders. The bulk of the traffic is carried by the luist Indian Railway, which taps the

' ' The GIrldili Coal-field,' by Saise, in Records, Geological Survey of I iidia, vol. xxvii, part iii (1894) ; 'The Bokaro Coal-field aiurihe Kamgarh Coal-field,' by Hughes, in Memoirs, Geological Survey of India, vol. vi, part ii (1867); ' The Karanpura Coal- fields,' Memoirs, Geological Survey of India, vol. vii, part iii (1869); 'The Itkhori Coal-field,' iT/i'W£?m-, Geological Survey of India, vol. vii, part ii (1872), by Ball; ' The Chope Coal-field,' Memoirs, Geological Survey of India, vol. viii, part ii (1872). As regards copper and tin, see 'Geological Notes on N. Hazaribagh,' by Mallet, in Records, Geological Surz'ey of India, vol. vii, part i (1874), and 'The Copper and Tin Deposits of Chota Nagpur,' by Dates, in Transactions, Federal Institute of Mining Engineers, vol. ix (1S95), p. 427.

District at Girldih, but a large amount of goods is carried on pack- bullocks and in bullock-carts.

The only railways at present open are the short branch line connect- ing Giridih with the East Indian main line at Madhupur, and the Gaya-Katrasgarh line recently constructed, which runs through the north-east of the District. The District board maintained in 1903-4 44 miles of metalled and 521 miles of unmetalled roads, besides 336 miles of village tracks. The most important roads, however, are those maintained by the Public Works department, amounting to 201 miles in length (188 miles metalled and 13 miles unmetalled), and including the grand trunk road, which runs for 78 miles through the District, and the road from Hazaribagh to Ranch!, of which 30 miles lie in the District, and the roads from Hazaribagh to Barhi and Bagodar and from Girldlh to Dumri, the aggregate length of which is 82 miles.

Famine

The District was affected by the famine of 1874. Since then the only severe famine was that of 1897, when distress was general over a broad belt running north and south through the District, the thanas most affected being Barhl, Kodarma, Bagodar, Ciumia, Ramgarh, Mandu, and Hazaribagh. Relief works were opened but were not largely attended, owing partly to the unwillingness of the wilder tribes to engage in unaccustomed forms of labour, and partly to a fear that the acceptance of famine rates of payment would tend to lower wages permanently ; a good deal of employment, however, was afforded by the District board, and gratuitous relief was given to beggars and destitute travellers. The daily average number of persons employed on relief works was highest (1,728) in May, while the number in receipt of gratuitous relief reached its maximum (6,836) in June. The expenditure amounted to Rs. 73,000, including Rs. 26,000 spent on gratuitous relief, and loans were granted to the extent of Rs. 51,000.

Administration

For administrative purposes the District is divided into two sub- divisions, with head-quarters at Hazaribagh and Giridih. The staff at Hazaribagh subordinate to the Deputy-Commis- Administration. sioner consists of three Deputy-Magistrate-Collectors, while the subdivisional officer of Girldlh is assisted by a Sub-Deputy- Collector.

The chief civil court is that of the Judicial Commissioner of Chota Nagpur. The Deputy-Commissioner exercises the powers of a Sub- ordinate Judge, and a Subordinate Judge comes periodically from Ranch! to assist in the disposal of cases. Minor original suits are heard by three Munsifs, sitting at Hazaribagh, Chatra, and G!rid!h. Rent suits under the Chota Nagpur Tenancy Act are tried by a Deputy-Magistrate-Collector at Hazaribagh, by the Munsifs who are invested with the powers of a Deputy-Collector for this purpose, and by the suhdivisional officer of Girldih ; appeals from their decisions are heard by the Deputy-Commissioner or the Judicial Commissioner of Chota Nagpur, Criminal cases are tried by the Deputy-Commissioner, The suhdivisional officer of Glridih, and the above-mentioned Deputy and Sub-Deputy Magistrates, and by the Munsif of Chatra, who has been invested with second-class powers. The Deputy-Commissioner possesses special powers under section 34 of the Criminal Procedure Code, and the Judicial Commissioner of Chota Nagpur disposes of appeals from magistrates of the first class and holds sessions at Hazaribagh for the trial of cases committed to his court. Hazaribagh is the least criminal District in Chota Nagpur, and crime is com- ])aratively light.

In 1835, the first year for which statistics are available, 86 separate estates paid a land revenue of Rs. 49,000. The number of estates increased to 244 in 1870-1, but after that date a number of the smaller estates were amalgamated with others and the total fell in 1903-4 to 157, with a demand of 1-33 lakhs. Of these estates, 72 are perma- nently settled, 82 are temporarily settled, and 3 are held direct by Government.

In Hazaribagh District the eldest son takes the entire estate, and provides for the other members of the family by assigning them smaller holdings as maintenance grants. There is thus no tendency to the excessive subdivision of estates which is found in Bihar. Besides these maintenance grants, jdgtrs to ghdtwdh, priests, servants, and others are common. The only unusual form ol jdgir is one known as putra- putrddik, which remains in the family of the grantee until the death of the last direct male heir, after which it reverts to the parent estate. The incidence of revenue is very low, being R. 0-1-4 per cultivated acre, or only 8 per cent, of the rental, which is Rs. 1-2-6 per cultivated acre. The highest rates are realized from rice lands, which are divided into three main classes : gaird, the rich alluvial lands between the ridges ; singd, the land higher up the slopes ; and bad, the highest land on which rice can be grown. The rates, which are lowest in the central plateau and highest in the Sakri valley, vary for gaird land from Rs. 3-10-8 to Rs. 5-5-4 per acre (average Rs. 4-5-4) ; for singd land, from Rs. 2-10-8 to Rs. 4 (average Rs. 3-10-8) ; and for bad land, from Rs. i-io~8 to Rs. 3-10-8 (average, Rs. 2-2-8). Other lands are classified as bdri or gharbdri, the well-manured land situated close to the village ; bdhirbdri, fairly good land situated farther from the home- stead ; chird, land set apart for growing paddy seedlings ; tdnr, barren land on the tops of the ridges ; and tarri or rich land on the banks or in the beds of rivers. For these the ryot usually renders predial services in lieu of rent.

Village lands are of four kinds. Manjhihas is a portion of the best land set apart for the head of the village. It is frequently sublet, some- times at a cash rent, but more often on the adhbatai system, under which each party takes half the produce. When held khas^ it is cul- tivated by the ryots for the proprietor, the latter supplying the seed and a light meal on the days when the villagers are working for him. Jlban is land in which the ryots have occupancy rights. Khiindwat or sdjivdt lands are those reclaimed from jungle or waste land, and the ryot and his descendants have a right of occupancy, paying rent at half the rate prevailing in the neighbourhood for jlban lands. Utkar land is that cultivated by tenants-at-will. The rents oi jlban and utkar lands are usually payable in cash, but in the Sakri valley the system of payment by assessment or division of the produce is common.

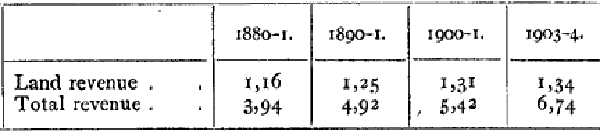

The following table shows the collections of land revenue and total revenue (principal heads only), in thousands of rupees : —

Outside the municipahties of Hazaribagh, Chatra, and GIrTdIh,

local affairs are managed by the District board. In 1903-4 its income

was Rs. 96,000, including Rs. 50,000 derived from rates ; and the ex-

penditure was Rs. 1,01,000, the chief item being Rs. 59,000 spent on

public works.

The District contains 18 police stations or thdnas, and 20 outposts. In 1903 the force subordinate to the District Superintendent consisted of 3 inspectors, 33 sub-inspectors, 54 head constables, and 431 con- stables. The Central jail at Hazaribagh has accommodation for 1,257 prisoners, and a subsidiary jail at Giridih for 21. The Hazari- bagh Reformatory school has accommodation for 357 boys.

Education is very backward, and only 2-6 per cent, of the population (5-2 males and 0-2 females) could read and write in 1901. The number of pupils under instruction increased from 6,234 in 1882-3 to 15,867 in 1892-3, but fell to 14,345 in iroo-i. In 1903-4, 16,440 boys and 2,014 girls were at school, being respectively i9'2 and 2-2 per cent, of the children of school-going age. The various missions maintain schools for the benefit of the aboriginal tribes. The most notable educational institutions are the Dublin University Mission First Arts college, and the Reformatory at Hazaribagh. The total number of institutions, public and private, in 1903-4 was 692, including the Arts college, 16 secondary, 643 primary, and 32 special schools. The expenditure on education was Rs. 1,12,000, of which Rs. 38,000 was met from Provincial funds, Rs. 31,000 from District funds, Rs. 800 from municipal funds, and Rs. 23,000 from fees.

In 1903 the District contained 7 dispensaries, of which 5 had accom- modation for 64 in-patients. The cases of 37,411 out-patients and 586 in-patients were treated during the year, and 1,570 operations were per- formed. The expenditure was Rs. 11,000, of which Rs. 1,200 was met from Government contributions, Rs. 2,000 from Local and Rs. 2,400 from municipal funds, and Rs. 5,000 from subscriptions.

Vaccination is compulsory only in the Hazaribagh, Girldih, and Chatra municipalities. In 1903-4 the number of persons successfully vaccinated was 41,000, or 36 per 1,000 of the population.

[Sir W. W. Hunter, Statistical Account of Bengal, vol. xvi (1877); Y. B. Bradley-Birt, Chota Nagpiir (1903).]

After 1947

1920s- 2023: tigers disappear, forests are empty

Raza Kazmi, January 30, 2023: The Indian Express

Hazaribagh in the Chota Nagpur plateau had once been home to a healthy population and diversity of predators, including one of the largest tigers ever found in India. Over the years, poaching and unmitigated industrialisation have laid its forests to waste

“Three miles from our winter home, and in the heart of the forest, there is an open glade… It was in this glade, which for beauty has no equal, that I first saw the tiger who was known throughout the United Provinces as ‘The Bachelor of Powalgarh’, who from 1920 to 1930 was the most sought-after big-game trophy in the province”, wrote Jim Corbett in Man-Eaters of Kumaon (1944). The Bachelor, described by hunters to be “as big as a Shetland pony” was arguably one of the biggest tigers to have ever lived.

However, unlike most other big cats Corbett shot, The Bachelor was no man-eater. At best he was a threat to the local cattle, though that was hardly a consolation to one of Corbett’s buffalo herder friends to whom the Bachelor was “a shaitan of a tiger, the size of a camel… big enough to eat a buffalo a day, and ruin him in twenty-five days”. The Bachelor met his end at the hands of Corbett in the spring of 1930.

Thirty-three years later, and seven years before tiger hunting would be banned in India, in another spring, in another land, more than a thousand kilometres away from the cool greens of the Shivaliks, a hunter was hot on the heels of a massive tiger that had been leaving “tracks almost the size of soup plates”. This giant, too, was no man-eater, though much like the Bachelor he, too, liked a few buffaloes every now and then. When the hunter, a maverick man named Syed Askari Hadi Ali Augustine Imam, finally saw the tiger for the first time, he described him as the size of “a polo pony”. This tiger too met his end, almost in the exact manner as the Bachelor – a bullet to his head that went through his skull.

SAHAA Imam, or ‘Tootoo’ Imam, as he was popularly known, was a spiry wrinkled nonagenarian in the twilight of his life by the time I first met him in 2012. He had arguably been, for a better part of the century, the most flamboyant character in the otherwise quiet and quaint town of Hazaribagh in Jharkhand. Son of Justice Syed Hasan Imam, president of the Indian National Congress in 1918, and India’s representative at the League of Nations in 1923, this former racer, hunter, sports-car aficionado, and equestrian had been christened ‘Tootoo’ by the virtue of the fact that as a child he had travelled with his family to the Valley of the Kings in Egypt to see the tomb and the sarcophagus of King Tutankhamun. A complete Anglophile, Tootoo, for a lot of townsmen, was the last “gora saheb” the British forgot to take back when leaving India.

As I waited for him in the drawing room of his sprawling bungalow, I was immediately drawn to a moulded, fading black-and-white image of a dead tiger with some people huddled behind it, kept atop the fireplace mantle. As I peered at it in the dimly-lit room, I was stunned. This had to be the largest tiger I had ever seen, with a head of absolutely unreal proportions. I had seen the famous photo of the Bachelor of Powalgarh, lying prostrate at Corbett’s feet, umpteen times. I had no doubt that the behemoth I was looking at outmatched him. I christened him ‘The Bachelor of Hazaribagh’.

Imam had shot our Bachelor, in the spring of 1963, in the forests of the northern escarpment of Hazaribagh plateau, not too far from his home. “When we examined him I could scarce believe my eyes. I have seen no tiger before or since with a head of the size he had. The rifle shown along the beast’s body is my .470 and will give scale to the picture. He had a mane on the top of his neck. In the picture, this looks like an enormous bulge of muscle on the neck. He had tremendous “mutton chop” whiskers”, Imam recounted in his book Brown Hunter (1979). “I believe this to be the biggest Indian tiger ever shot considering body length only [which was 7 ft 5 inches] and excluding the tail.”, wrote Imam while noting that this tiger had a curiously short tail.

“I am quite deaf you see, could you speak louder?” said Tootoo uncle in his very British accent as I shot a barrage of queries about the photograph and the tiger at him. “That tiger, could you tell me more about him?” I repeated while gesturing towards the photo frame on the fireplace mantel.

His sunken eyes suddenly widened, accentuating the thousand wrinkles on his face further and he extended his shrivelled hands to draw his walking stick. With a gentle heave, he gingerly got up. “Come with me,” he said and slowly walked me to a wall where hung a wired skull, evidently of a big cat. “This is him,” he rasped.

He went quiet momentarily, almost as if to muster all his strength. Then, he began speaking animatedly, recalling the story of our Bachelor, with generous gesticulations of the hand. Of the hundreds of wild tigers he had seen all over India – from Assam to Kumaon, the Western Ghats to the Eastern Ghats – and even Nepal during his decades of hunting, no tiger, he asserted, came even remotely close to being as immense as the Bachelor of Hazaribagh. With a twinkle in his eye, he recounted his life as a young man, his Santhal hunter friends, and the days and nights spent tramping the forests with them in the wildlife haven that Hazaribagh was.

“It’s all gone now, all gone,” he finished as abruptly as he had begun, the light going out of his eyes, his spindly frame hunching over once more. I escorted him back to his sofa, where an old decaying trophy-head of a tiger shot by him in the hill adjoining his bungalow stared down at us. Imam passed away in 2018, a few months shy of his 98th birthday.

“The Kul [tiger] has been gone for many years now. Pothiya [leopards] are also no longer heard of. All the large wild animals that we once had in plenty disappeared over the years,” said Lambu, one of the last “native shikaris” – a term used by the British for the Adivasi trackers and hunters whose jungle-craft was the key to any hunt – alive today, waving his hand towards the forests at a distance as he warmed his feet over the dying embers of a fire.

It was in these very forests around his village, Jarwadih, that the Bachelor of Hazaribagh was shot at a place called Chunakhan. Lambu, a Santhal Adivasi – a tribe whose hunting skills have been the stuff of legends – was a permanent member of Tootoo’s team of trackers and had been instrumental in bringing Bachelor to the gun. But that was then. In the decades that followed, the wildernesses of Hazaribagh and Powalgarh that birthed the two Bachelors would traverse two vastly differing trajectories.

The forests of Powalgarh, now an eponymously named conservation reserve, continue to reverberate with the roars of the tiger. Abutting the famous Corbett tiger reserve, they still harbour among the highest densities of wild tigers in the entire world. Moreover, Powalgarh’s forests are an integral part of Uttarakhand’s massive tiger landscape that spans across the Shivaliks of Dehradun district in the west to Nainital in the east, beyond which it merges seamlessly into the Terai tiger landscape of Nepal and Uttar Pradesh.

The home of Hazaribagh’s Bachelor, however, withered away long ago. It has been decades since the tigers’ roar fell silent not just across the forests of Hazaribagh, but the entire length and breadth of the Chota Nagpur plateau, of which Hazaribagh was an integral part. Tigers were practically wiped out across Hazaribagh’s forests by the late 1980s, and the last resident tiger of the forests of Hazaribagh Wildlife Sanctuary disappeared in 1994. Poaching was the primary reason. The destruction of wildlife, however, didn’t stop at tigers.

Hazaribagh was once famed across Chota Nagpur not only as the land of thousand tigers, but also as the preeminent stronghold of the sambar deer, the primary prey of the big cat. The abundance of prey-species in Hazaribagh allowed it to harbour a very healthy population and diversity of predators – leopards, very large packs of wild dogs, as well as wolves. However, within a decade of the tiger’s disappearance, Hazaribagh’s forests had been emptied of all its sambar deer, and the cheetal deer were reduced to a few dozen animals.

With them disappeared the predators — leopards and wild dogs. With the forest department turning a blind eye, rampant bushmeat hunting wiped out nearly all medium and large mammalian fauna across Hazaribagh. It was a complete collapse of the food chain. Today, the 186.25 sq. km.

Hazaribagh Wildlife Sanctuary, once the beating heart of Hazaribagh’s larger wilderness that spanned more than 3,000 sq km, is a classic example of the “empty forest syndrome” that afflicts nearly all of Jharkhand. Apart from wild boars, and a rare barking deer, a few captive deer and nilgai in an enclosure at Rajderwa – named so after the hunting lodge of the Raja of Ramgarh who once owned this forest as his private hunting reserve – is all that the sanctuary has to show for its ungulate fauna. A few of these captive-bred cheetal were released into the sanctuary in recent years but it hasn’t made any difference to the steady ecological decline of the forest.

However, while the roars of the tiger and sawing of the leopards might no longer echo through the forests of Hazaribagh, these forests have not been quiet. On quiet days, one can hear the massive crushers from the many stone quarries that persistently chip away at the edge of the forest right outside the wildlife sanctuary, leaving behind ugly barren craters in their wake.

One can also pick up the constant drone of vehicles as thousands of them whiz through the newly-constructed four-lane expressway that cuts through the heart of the sanctuary. Elsewhere, in many of the district’s forests, one can hear the distant booming blasts emanating from lands that were once cloaked with forests but are now hollowed out for the “black gold” that lies in their belly. Thousands of large Hyva trucks tar hinterland forest roads black with coal dust.

The patch of forest which once pulsated with the call of the Bachelor of Hazaribagh in the early 1960s now trembles with the ceaseless tremors of convoy after convoy of heavy coal-laden Hyvas passing through it during the day and into the night.

I re-read the words of F.B. Bradley-Birt, a British bureaucrat, who had described Hazaribagh thus more than a century ago – “This is the garden of Chota Nagpore, and that the motto over the old gateway of the Emperors at Delhi might well be written of Hazaribagh: ‘If there is a paradise on earth, it is here, it is here.’ No sooner had I read this excerpt that a little voice suddenly whispered the words of Late Tootoo uncle into my ears — “It’s all gone now. It’s all gone”.