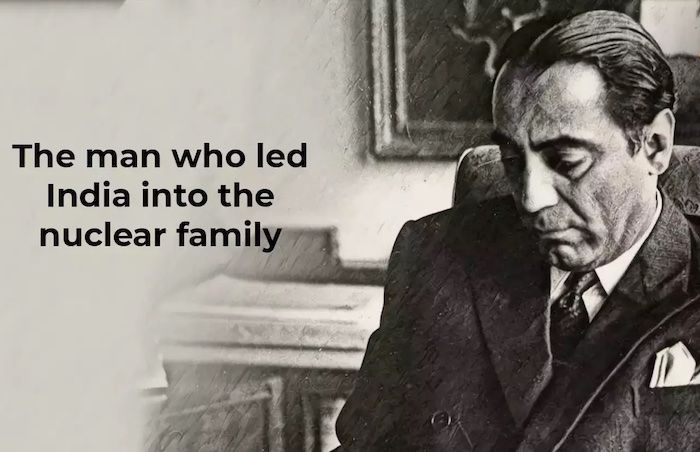

Homi Bhabha

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Additional information may please be sent as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A brief biography

A: By Rishika Singh

Rishika Singh , March 20, 2023: The Indian Express

Early life, association with Tatas and years at Cambridge

Homi Jehangir Bhabha was born on October 30, 1909, to a wealthy Parsi family from Mumbai. His grandfather was the Inspector General of Education in the State of Mysore.

Bhabha’s father Jehangir Hormusji Bhabha was educated at Oxford and later qualified as a lawyer. His mother Meherbai was the granddaughter of Sir Dinshaw Maneckji Petit, a textile factory owner in Bombay who was known for his philanthropic efforts.

Bhabha attended schools in Mumbai, joining Elphinstone College and then the Royal Institute of Science in the city. In 1927, Bhabha attended the Gonville and Caius College in Cambridge.

Both his uncle Sir Dorab J. Tata – the son of Tata group’s founder Jamsetji Tata – and his father wanted Bhabha to become an engineer and work at the Tata Iron and Steel Company at Jamshedpur. But once at college, he became more interested in theoretical physics. In 1928, he wrote to his father:

“I seriously say to you that business or job as an engineer is not the thing for me. It is totally foreign to my nature and radically opposed to my temperament and opinions. Physics is my line. I know I shall do great things here. For, each man can do best and excel in only that thing of which he is passionately fond, in which he believes, as I do, that he has the ability to do it, that he is in fact born and destined to do it… It is no use saying to Beethoven ‘You must be a scientist for it is great thing’ when he did not care two hoots for science; or to Socrates ‘Be an engineer; it is work of intelligent man’. It is not in the nature of things. I therefore earnestly implore you to let me do physics.”

At Cambridge, he was taught by Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac, a Mathematics professor who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1933 with Erwin Schrodinger for their work in quantum theory. Bhabha went on to receive various scholarships. His work centred around cosmic rays and he earned a PhD in nuclear physics in 1934.

Prof. Devendra Lal, an Indian nuclear physicist, once wrote that Bhabha’s work here developed on several issues relating to cosmic ray phenomena and the interactions of electrons, protons and photons at high energies, in context to issues in the fields of quantum mechanics and relativity. “These advances were made by him in the 30’s, when little was known about the nature of high-energy interactions,” he said.

Homi J Bhabha’s work in India

Bhabha came to India in 1939 for some time, but his plans to return to England for his academic work were halted because of the Second World War’s onset. In 1940, he joined the Indian Institute of Science at Bangalore, where a Readership in Theoretical Physics was specially created for him. Future Nobel laureate CV Raman was then the Director of the Institute. He was made a Professor in 1944. Vikram Sarabhai also spent a short period at the Institute when Bhabha was there.

When Bhabha was working at the IISc, higher-level facilities for research on Physics were limited in India. In March 1944, he wrote to the Sir Dorab J. Tata Trust for establishing “a vigorous school of research in fundamental physics”.

Writing his proposal, he said: “There are, however, scattered all over India competent workers who are not doing as good work as they would do if brought together in one place under proper direction. It is absolutely in the interest of India to have a vigorous school of research in fundamental physics… If much of the applied research done in India today is disappointing or of very inferior quality it is entirely due to the absence of sufficient number of outstanding pure research workers.”

An early proponent of nuclear energy, he wrote, “Moreover, when nuclear energy has been successfully applied for power production in say a couple of decades from now, India will not have to look abroad for its experts but will find them ready at hand.”

The trustees accepted Bhabha’s proposal the Institute began work in April 1944. Mumbai was chosen as the location as the Government of Bombay showed interest in becoming a joint founder of the proposed institute. The institute, named Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), was inaugurated in 1945. The present building of the Institute was inaugurated by then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in January 1962. Nehru, with whom Bhabha also had a personal friendship, earlier laid its foundation stone in 1954.

The Institute received financial support from the Government of India from its second year, through the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) and the Ministry of Natural Research and Scientific Research.

CV Raman would describe Bhabha, whose interests also spanned classical music and sketching, as “the modern equivalent of Leonardo da Vinci”. According to his brother Jamshed, “For Homi Bhabha, the arts were not just a form of recreation or pleasant relaxation; they were among the most serious pursuits of life and he attached just as much importance to them as to his work in mathematics and physics. For him, the arts were, in his own words, ‘what made life worth living’.”

Aiding the growth of institutions and nuclear energy

Bhabha was instrumental in picking the people who would be associated with the institute and gave them opportunities to grow. This was also seen in his passion for the development of nuclear energy in India as a field of study.

On April 26, 1948, he sent a note on a new ‘Organisation of Atomic Research in India’ to Nehru, writing: “The development of atomic energy should be entrusted to a very small and high-powered body composed of say, three people with executive power, and answerable directly to the Prime Minister without any intervening link.”

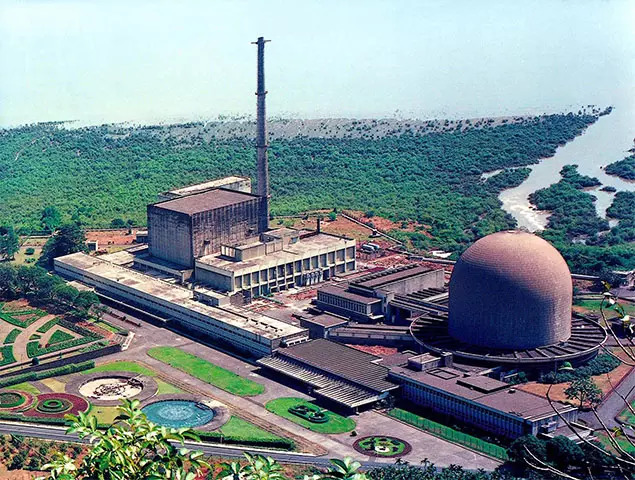

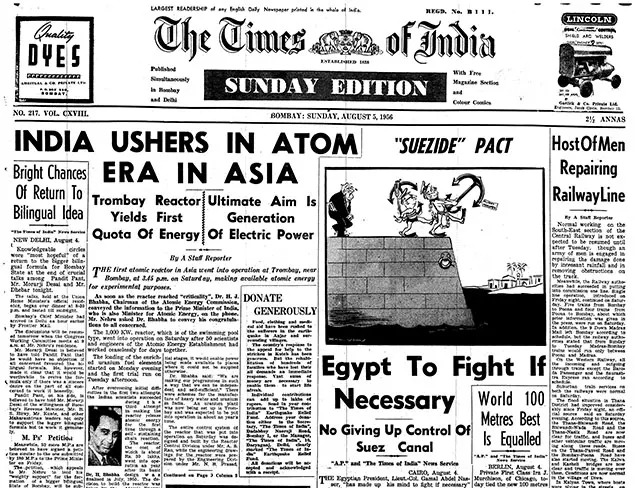

He also detailed the structure of such a body and its functioning. The Government of India accepted Bhabha’s proposal within a few months after its submission and with the promulgation of the Indian Atomic Energy Act 1948, the Atomic Energy Commission was formed in August 1948. Later in 1954, he led efforts to establish the Atomic Energy Establishment (AEET) in Trombay, Maharashtra, for a multidisciplinary research program.

Throughout his life, Bhabha noted the importance of developing opportunities for science to flourish in India. In an address to the Assembly of the Council of Scientific Unions in 1966, Bhabha said, “It is interesting to note that practically all the ancient civilizations of the world, Persia, Egypt, India, and China, were in countries which are today underdeveloped… What the developed countries have and the underdeveloped lack is modern science and an economy based on modern technology.”

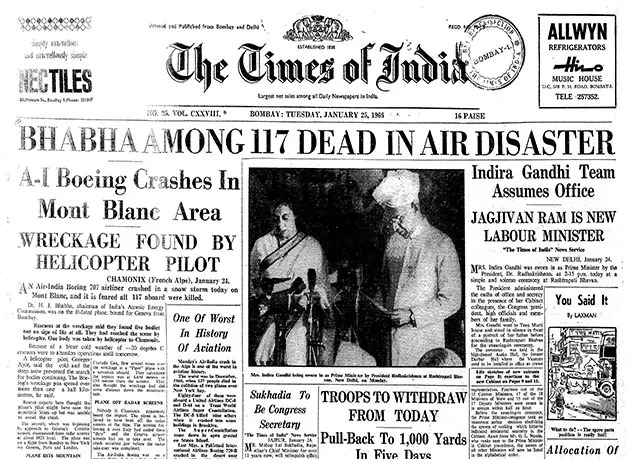

Homi Bhabha died in a plane crash on the way to Geneva on January 24, 1966, and to date, theories surround its circumstances. AEET was later renamed the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) to mark his role in spearheading the institution’s growth. Bhabha had also served as the head of India’s nuclear program until his death.

B: By Yogita Rao

Yogita Rao, Oct 30, 2021: The Times of India

From: Yogita Rao, Oct 30, 2021: The Times of India

From: Yogita Rao, Oct 30, 2021: The Times of India

From: Yogita Rao, Oct 30, 2021: The Times of India

From: Yogita Rao, Oct 30, 2021: The Times of India

From: Yogita Rao, Oct 30, 2021: The Times of India

From: Yogita Rao, Oct 30, 2021: The Times of India

From: Yogita Rao, Oct 30, 2021: The Times of India

From: Yogita Rao, Oct 30, 2021: The Times of India

From: Yogita Rao, Oct 30, 2021: The Times of India

Had Homi Bhabha lived his father’s dream, he would have become a corporate man, not the scientist who birthed newly independent India’s nuclear programme. Jehangir Bhabha, a wealthy Parsi lawyer, wanted his elder son to complete his mechanical engineering at Gonville and Caius College in Cambridge and join the Tatas, but the young Homi’s interest had shifted from engineering to theoretical physics and mathematics by then.

“I seriously say to you that business or a job as an engineer is not the thing for me,” 18-year-old Homi wrote home. “It is totally foreign to my nature and radically opposed to my temperament and opinions. Physics is my line. I know I shall do great things here.”

In another letter to his father, he wrote he had no wish to head a big firm. “It is no use saying to Beethoven, ‘You must be a scientist for it is a great thing’ when he did not care two hoots for science; or to Socrates, ‘Be an engineer, for it is the work of an intelligent man’.” Jehangir Bhabha replied he was neither Socrates nor Einstein but agreed to the career shift on condition that Homi complete his engineering with first class, which he did.

Eventually, circumstances brought the young scientist back to India in an era when it needed to establish world-class research institutions. “At a time when India was not even designing indigenous bicycles, Bhabha was thinking of building nuclear reactors,” is how former principal scientific adviser R Chidambaram sums up his legacy.

The decades Homi Bhabha spent at home after returning from Europe shaped the nuclear programme as well as the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR). The Atomic Energy Establishment (named Bhabha Atomic Research Centre after his untimely death) was set up barely seven years after Independence and was the place where Asia’s first research reactor went critical in 1956. BARC and TIFR, in turn, spawned projects, including the space programme, C-DOT (for telecom) and India’s first mainframe computer.

European in manner, nationalist at heart

Born on October 30, 1909, Bhabha completed schooling at Bombay’s Cathedral and John Connon School, which “did much to foster a love for science”. His paternal aunt was the wife of Sir Dorabji Tata (Tata group chairman, 1904-38). Bhabha grew up in a household of European etiquette frequented by tall leaders and filled with discussions between the Tatas and luminaries like Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi; these remained with him forever.

After attending Elphinstone College, he joined the Royal Institute of Science (now the Institute of Science), where he first heard about cosmic rays – a subject he later specialised in – in a lecture by American physicist AH Compton. A year later, he left for Cambridge, where he had a chance to work in the Cavendish Laboratory, which was reputed for big breakthroughs, including the discovery of neutrons and high-energy protons. He completed his PhD under physicist RH Fowler’s supervision.

On a travelling scholarship in Europe, Bhabha forged relationships with leading physicists, including Wolfgang Pauli, Niels Bohr and Enrico Fermi. He published his first paper here on ‘The Passage of Fast Electrons and the Theory of Cosmic Showers,’ and discovered the electron-positron scattering process, what came to be known as the ‘Bhabha scattering’.

The outbreak of WW-II in 1939 forced Bhabha, who was vacationing in India, to stay back. He was keen to return to Cambridge, but scientists there were pushed into the war effort and fundamental research had taken a backseat. After assessing a few offers, he took the reader’s post at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in Bangalore that was headed by CV Raman. But soon, he was nurturing “the idea of founding a first-class research school for advanced physics in Bombay”. In a fund-raising letter to Sorab Saklatvala, chairman of Sir Dorabji Tata Trust, in March 1944, Bhabha said, “It is absolutely in the interest of India to have a vigorous school of research in fundamental physics.…If much of the applied research done in India today is disappointing…it is entirely due to the absence of a sufficient number of outstanding pure research workers.” The trustees accepted the proposal and TIFR was born in May 1945.

Enabler and institution builder

Bhabha believed in seeking out an outstanding researcher and building a lab around him. In a letter to physicist S Chandrasekhar, he offered to create a chair for him at TIFR. “I have recently come to the view that provided proper appreciation and financial support are forthcoming, it is the duty of people like us to stay in our own country and build outstanding schools of research.”

“Bhabha sought to bring back home established Indian scientists, who were leaders in their fields of research, back home and allowed them to flourish here. He knew radio astronomy was important, so he got Govind Swarup and together they built a radio telescope in Ooty. He got Obaid Siddiqi and created a molecular biology unit. Similarly, he got Homi Sethna for chemical engineering, Raja Ramanna and MGK Menon for physics, Brahm Prakash for metallurgy, and AS Rao for electronics. He built a leadership swarm around him,” said Chidambaram, adding that the culture Bhabha established helped develop more leaders.

At BARC, the bulk of students in the training school came from the hinterland. “We looked at people’s logical and analytical abilities while hiring. Even if a person could not converse in English, he was allowed to speak in Hindi or another regional language. The talent hunt programme at BARC never cared for people’s background. We may all appear rustic, but we can deliver,” said former director of BARC and former chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, Anil Kakodkar.

Vision for nuclear power

By the early 1940s, Bhabha was already championing the cause of nuclear energy. He wrote to Saklatvala in 1944 about harnessing it for power production. “When nuclear energy is successfully applied for power production in a couple of decades from now, India will not have to look abroad for its experts.” This was 18 months before the first N-weapon bombed Hiroshima. The war’s horrors made Bhabha vocal about universal disarmament, but he remained optimistic on the use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes and hinted at its effectiveness as a deterrent against powerful nations.

Unlike Raman, whose passion was fundamental research, Bhabha was application-minded, says TIFR director S Ramakrishnan. “He wanted to primarily start a fundamental research institution but with a keen understanding that this would lead to applications that would be useful for young India, especially power.”

Bhabha’s ties with the political establishment helped him guide the fledgling science sector freely. “Nehru was a forward-looking leader and was encouraging science in a big way. It was Bhabha’s friendship with Nehru that enabled him to get timely support. He called Nehru ‘bhai’,” said Chidambaram. The Cambridge-educated politician and the Cambridge-educated physicist had much in common. In one of his last speeches, Bhabha acknowledged the “immense” debt Indian scientists and science owed the first PM.

Path to energy independence

Backed by generous funding (Rs 10 crore in 1964), Bhabha conceived a three-stage N-power programme to secure India’s long-term energy goals using the vast domestic reserves of thorium. Kakodkar says this objective has been met in terms of developing technology, “But in terms of delivery to the nation, probably his vision was much bigger than what we have delivered. The main reason being…we had to face a lot (of embargoes) after 1974 (Pokhran test) and they only grew after 1998.”

Untimely end

Bhabha died in an air crash near Mont Blanc in the Alps on January 24, 1966. He was travelling to Geneva en route to Vienna to attend a meeting of the International Atomic Energy Agency. The loss sent the entire Indian scientific community into mourning. “He was a great visionary. The entire atomic energy programme was due to him. He indirectly started the Indian space programme too. The development of electronics (in India) owes its origin to Bhabha,” said renowned scientist CNR Rao, making a case for a posthumous Bharat Ratna.

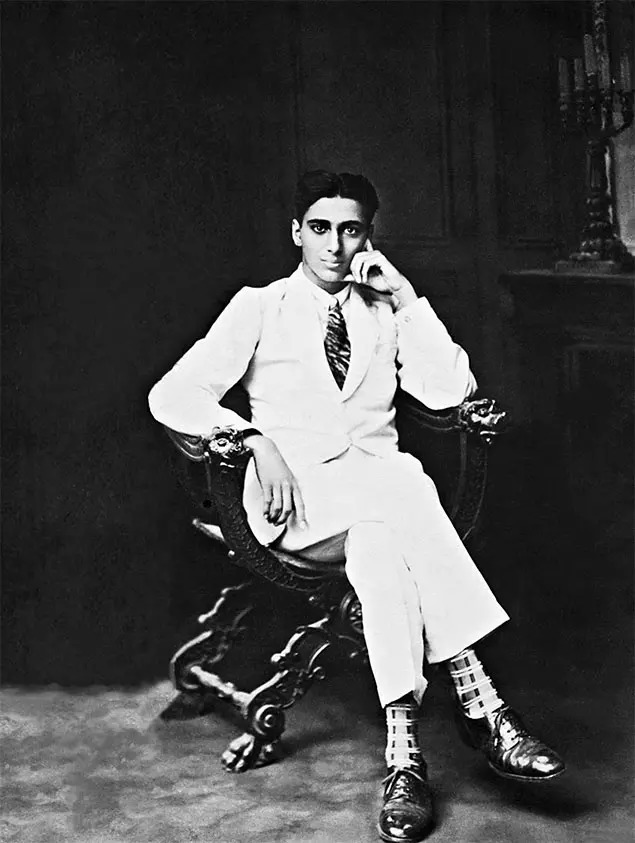

Portrait of a scientist as a young man

Homi Bhabha took art lessons from a young age and won several prizes in the under-18 category of Bombay Art Society’s annual exhibitions. His self-portrait (left) at the age of 17, which he attempted in the style of Rembrandt, was one of the winners. His sketch of his mentor, the Nobel-winning Danish physicist Niels Bohr, is from 1960.