Hoshiarpur District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Hoshiarpur District

Physical aspects

Submontane District in the Jullundur Division,Punjab, lying between 30° 59' and 32° 5' N. and 73° 30' and 76° 38' E., with an area of 2,244 square miles. Its eastern boundary consists of the western slopes of the Sola Singhi hills, a range of the Outer Himalayan system, which separates it from Kangra District and Bilaspur State, and whose highest elevation (3,896 feet) within the District is at Bharwain, its summer station. Parallel with this range and lying north-west-by-south-east runs the northern section of the Siwalik range, locally known Katar Dhar. Between these ranges is the

Jaswan or Una Dun, a broad fertile valley, watered by the Sohan stream, which rises in its northern extremity and flows south-east until it falls into the Sutlej near Anandpur. The latter river, breaking through the Sola Singhi range near Bhabaur, flows south-east through the Dun until at Rupar it cuts through the Siwaliks and thence flows west. The south-east corner of the District, the Jandbhari ildka, lies on the left bank of the Sutlej ; but that river forms its boundary on the extreme south-east and south, separating it from Ambala. On the north the Beas also breaks through the Sola Singhi hills, and sweep- ing round the northern end of the Siwaliks flows thence almost due south, dividing the District from Kangra on the north and Gurdaspur on the west.

Hoshiarpur thus consists of a long, irregular oval, the Siwaliks forming its axis and dividing it into two unequal parts, of which the western is the larger. Hiis part is a rich well-wooded submontane tract, which slopes south-westwards from the Siwaliks towards the borders of the Kapurthala State and JuUundur District. It is watered by only two perennial streams of any size : namely, the western or Black Bein, which rises in the swamps near Dasuya and flows into Kapurthala ; and the eastern or White Bein, which rises near Garh- shankar, and, after a short winding course through the tahsil of that name, turns sharply to the north and meanders along the JuUundur border.

The principal feature of this submontane tract is the chos, or seasonal torrents, which, rising in the Siwaliks, spread like a net- work over the plain. At an earlier period the silt washed down from the Siwaliks must have formed the alluvial plain to their west and caused its fertility, but owing to the deforestation of those hills the chos have for a considerable time been destroying it. Dry in the rainless months, they become raging torrents after heavy rain ; and, passing through the sandy belt which lies belcnv the western slope of the hills, they enter the plain, at first in fairly well-defined channels, but finally spreading over its surface and burying the cultivation under infertile sand. At a special inquiry held in 1895-6, it was found that no less than 147 s(}uare miles were Covered by these torrent-beds, an increase of 72 since 1852. The Punjab Land Preservation {Chos) Act (Act II of 1900) has been extended to the Siwaliks, in order to enable the Local Government to limit the rights of grazing and wood-cutting as a preliminary step towards their reafforestation, which, it is hoped, will remedy the damage now being caused by the hill torrents.

Geologically, the District falls into two subdivisions: a south-western, composed of alluvium ; and a north-eastern, comprising the Siwalik and sub-Himalayan ranges running north-west from the Sutlej. These ranges are formed of the sandstones and conglomerates of the upper Siwalik series, which is of Upper Tertiary (pliocene) age ^

The southern portion of the District hardly differs botanically from the general character of the Central Punjab, though the mango and other sub-tropical trees thrive particularly well in cultivation. The submontane part has a true Siwalik flora, and in one valley in the extreme north of the District the sal {Shorca rolnista) finds its northern limit. The ber {Zizyphus Jiijuba) is plentiful. Wild animals include leopards (in the hills), hyenas, wolves, antelope, deer, &c. Feathered game is fairly plentiful.

Owing to the proximity of the hills, the heat in the plains is never excessive, while Bharwain, the summer station of the District, enjoys a mild hot season. "^Phe chief cause of mortality is fever. Plague entered the District from Jullundur in 1897; and, in spile of con- siderable opposition culminating in a serious riot at Garhshankar, vigorous measures were for three years taken to stamp out the disease, and to some extent successfully.

The annual rainfall varies from 31 inches at Garhshankar to 34 at Hoshiarpur. Of the rainfall at the latter place, 28 inches fall in the summer months, and 6 in the winter. The greatest fall rectMtled of late years was 79 inches at Una in 1881-2, and the least 13 inches at Dasuya in 1901-2.

History

Tradition associates several Places, notably Dasuva, with the Tan davas of the Mahabharata, but archaeological remains are few and unimportant. Prior to the Muhammadan invasions,the modern District undoubtedly fijrmed part 01 the Katoch kingdom of Trigarlla or Jullundur; and when at an unknown date that kingdom broke up into numerous petty principalities, the Jaswan Rajas, a branch of the Katoch dynasty, established themselves Medlicott, 'On llic Sulj-lliinalayan Ranges between The G.inyeb ami Ka\i,' Memoirs, Geological Survey 0/ India, vol. iii, j)t. ii, VOL. Xlll. (I in the Jaswan Dun. The plauis probably came pernianentl\- under Muhammadan rule on the fall of JuUundur in 1088, but the hills remained under Hindu chieftains. In 1399 Timur ravaged the Jas- wan Dun on his way to capture Kangra fort. At this period the Khokhars appear to have been the dominant tribe in the District ; and in 142 1 Jasrath, their chief, revolted against the weak Saiyid dynasty, but in 1428 he was defeated near Kangra. After that event several Pathan military colonies were founded in the plain along the base of the Siwaliks, and Bajwara became the head-quarters.

The fort of Malot, founded in the reign of Sultan Bahlol by a Pathan grantee of the surrounding country, was Daulat Khan's stronghold. It played an important part in Babar's invasion, and after its surrender Babar crossed the Siwaliks into the Jaswan Diln and marched on Rupar. Under Sher Shah, the governor of Malot ruled all the hills as far as Kangra and Jammu, and organized some kind of revenue system. By this time the Dadwals, another Katoch family, had estab- lished themselves at Datarpur in the Siwaliks. On Akbar's accession, the District became the centre of Sikandar Suri's resistance to the Mughal domination ; but he was soon reduced, and in 1596 the Jaswans were disposed of without actual fighting. After this the District settled down under the Mughal rule and was included in Todar Mai's great revenue survey.

The Rajas of Jaswan and Datarpur retained possession of their fiefs until 1759, when the rising Sikh adventurers, who had already estab- lished themselves in the lowlands, commenced a series of encroachments upon the hill tracts. The Jaswan Raja early lost a portion of his dominions ; and when Ranjit Singh concentrated the whole Sikh power under his own government, both the petty Katoch chiefs were com- pelled to acknowledge the supremacy of Lahore. At last, in 1815, the ruler of Jaswan was forced by Ranjit Singh to resign his territories in exchange for an estate held on feudal tenure {Jdg'ir) ; and three years later his neighbour of Datarpur met with similar treatment.

Meanwhile, the lowland portion of the District had passed completely into the hands of the Sikh chieftains, who ultimately fell before the absorbing power of Ranjit Singh; and by the close of i8i8 the whole country from the Sutlej to the Beas had come under the government of Lahore. A small [)ortion of the District was administered by deputies of the Sikh governors at Jullundur; but in the hills and the Jaswan Dun, Ranjit Singh assigned most of his conquests to feudal rulers {Jdgtrdars), among whom were the deposed Rajas of Datarpur and Jaswan, the Sodhis of Anandpur, and the Sikh prelate Bedi Bikrama Singh, whose head-quarters were fixed at Una. Below the Siwalik Hills, Sher Singh (afterwards Maharaja) held Hajipur and Mukcrian, with a large tract of country, while other great tributaries received assignments elsewhere in the lowland region. Shaikh Sandhe Khan had charge of Hoshiarpur at the date of the British annexation, as deputy of the Jullundur governor.

After the close of the first Sikh War in 1846, the whole tongue of land between the Sutlej and the Beas, together with the hills now constituting Kangra District, passed into the hands of the British Government. The deposed Rajas of Datarpur and Jaswan received cash pensions from the new rulers, in addition to the estates granted by Ranjit Singh ; but they expressed bitter disappointment that they were not restored to their former sovereign positions. The whole of Bedi Bikrama Singh's grant was resumed, and a pension was offered for his maintenance, but indignantly refused ; while part of the Sodhi estates were also taken back. Accordingly, the outbreak of the Multan War and the revolt of Chattar Singh, in 1848, found the disaffected chief- tains ready for rebellion, and gave them an opportunity for rising against the British power. In conjunction with the Kangra Rajas, they organized a revolt, which, however, was soon put down without serious difficulty.

The two Rajas and the other ringleaders were captured, and their estates were confiscated. Raja Jagat Singh of Datarpur lived for about thirty years at Benares on a pension from the British Government. Umed Singh of Jaswan received a similar allowance ; Ran Singh, his grandson, was permitted to reside at Jammu in receipt of his pension ; and on the assumption by Queen Victoria of the Imperial title in January, 1877, the jaglr confiscated in 1848 was restored to Tikka Raghunath Singh, great-grandson of the rebel Raja, and son-in-law of the Maharaja of Kashmir. Bedi Bikrama Singh followed Chattar Singh at Gujrat, but surrendered at the close of the war and obtained leave to reside at Amritsar. His son, Sujan Singh, receives a Government pension, and has been created an honorary magistrate. Many other local chieftains still retain estates, the most noticeable being the Ranas of Manaswal and the Rais of Bhabaur. The sacred family of the Sodhis, lineal descendants of Ram Das, the fourth Sikh Guru, enjoy considerable pensions.

The Mutiny did not affect this District, the only disturbances being caused by the incursion of servants from Simla, who spread exaggerated reports of the [)anic there, and the rapid march of a party of mutineers from Jullundur, whcj passed along the hills and escaped across the Sutlej before the news had reached head-quarters.

Population

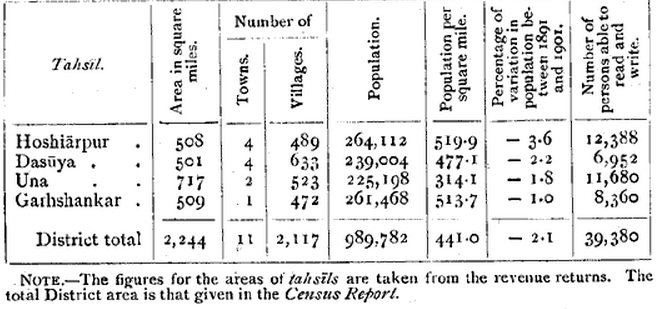

The population of the District at the last four enumerations was : (1868) 937,699, (r88i) 901,381, (1891) 1,011,659, and (1901) 989,782, dwelling in ri towns and 2,117 villages. It decreased by 2-1 per cent, durmg the last decade, the decrease being greatest in the Hoshiarpurtahsil(3-6) and least in Garhshankar. The density of the population is high. The District is divided into the four tahsils of Hoshiarpur, Dasuya, Una, and Garhshankar, the head-quarters of each being at the place from which it is named. The chief towns are the muni- cipalities of Hoshiarpur, the head-quarters of the District, Tanda- Urmar, Mariana, Garhdiwala, Una, Anandpuk, Mukerian, Dasuva, and Miam.

The following tabic shows the chief statistics of population in 1901 ; —

Hindus (603,710) comprise more than 60 per cent, of the total; Muhammadans number 312,958, or 32 per cent.; and Sikhs, 71,126, or 7 per cent. Punjabi is the language chiefly spoken.

The Jats or Jats (153,000) are first in point of numbers, comprising 15 per cent, of the total. They are chiefly Hindus, but include 35,000 Sikhs and 26,000 Muhammadans. The next most numerous are the Rajputs (94,000), who comprise more than 9 per cent, of the popu- lation ; they are mostly Hindus in the hills and Muhammadans in the plains. The Gujars (78,000) are a pastoral people, who are found mainly in the Siwaliks. The Pathans (7,000) are descendants of colonists planted by the Afghan invaders ; their villages originated in small brick fortifications, and are disposed partly in a long line parallel to the Siwaliks, as a protection against invasion from the hills, partly in a cluster guarding the Sri Gobindpur ferry on the Beas.

The Mahtons (10,000) are by their own account Rajputs who have descended in the social scale owing to their practice of widow mar- riage. They are either Hindus or Sikhs. The Kanets (1,700) are said to have the same origin as the Mahtons, and are ecjually divided between Hindus and Sikhs. The Arains (35,000) and Sainis (45,000) are industrious and careful cultivators \ the former are entirely Muham- madans, the latter Hindus or Sikhs. Other landowning tribes are the Awans (13,000) and Dogars (5,000), who are chiefly Muhammadans, and Ghirths (47,000), locally known as Bahtis and Chahngs, who are almost entirely Hindus. The Brahmans (80,000) are extensive land- holders in the hills and also engage in trade. Of the commercial classes, the KhattrTs (21,000) are the most important. Of the menial tribes may be mentioned the Chamars (leather-workers, 121,000), Chuhras (scavengers, 19,000), Jhlnwars (water-carriers, 24,000), Julahas (weavers, 24,000), Kumhars (potters, 11,000), Lobars (blacksmiths, 16,000), Nais (barbers, 14,000), Tarkhans (carpenters, 33,000), and Telis (oil-pressers, 12,000). About 60 per cent, of the population are dependent on agriculture.

The Ludhiana Mission has a station at Hoshiarpur, dating from 1867, and five out-stations in the District; its staff consists of 20 persons, with Scripture-readers and catechists, and includes a qualified lady doctor. The District contained 785 native Christians in 1901.

The .SivvALiK Hills, which form the backbone of the District, are for the most part soft sandstone, from which by detrition is formed a belt of light sandy loam known as the Kandi tract, lying immediately at their foot. This soil requires frequent, but not too heavy, showers, and the tract is to a large extent overspread with shifting sand blown from the torrent beds. Parallel to this comes a narrow belt, in which the loam is less mixed with sand ; and this is followed by the exceptionally fertile Sirwal belt, in which the spring-level is near the surface, and the loam, little mixed with sand except where affected by the hill torrents, is of a texture which enables it to draw up and retain the maximum of moisture. South-east of Garhshankar is a tract of clayey loam, probably an old depression connected with the Rein river, while north of Dasilya, and so beyond the range of the Siwalik denudation, is an area probably formed by the alluvion of the Beas, which is one of the most fertile in the District. The soil of the Una valley is for the most part a good alluvial loam, especially fertile on the banks of the Sutlej.

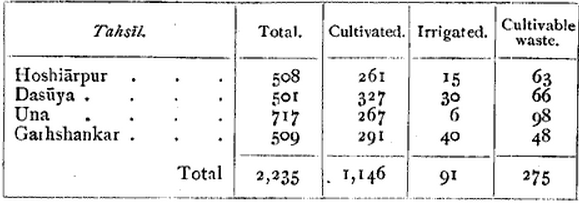

The District is held almost entirely on the bhaiyachdrd and pattldCxri tenures, zamtnddri lands covering only about 120 square miles. The area for which details are available in the revenue records of 1903-4 is 2,235 square miles, as shown below : —

The chief crops of the spring liarvest are wheat and gram, which

occupied 452 and 225 square miles respectively in 1903-4. Barley

occupied only 27 square miles. There were 154 acres of poppy.

In the autumn harvest maize is the most important crop (212 square

miles), and forms the staple food of the people ; pulses occupied

81 square miles and rice 39. Very little great or spiked millet is

grown. Sugar-cane is a very valuable crop, covering 38 square miles.

Cotton occupied 27 square miles.

The cultivated area increased by about 3 per cent, during the twenty years ending 1901, its extension having been much hindered by the destructive action of the mountain torrents. Outside their range of influence, almost every cultivable acre is brought under the plough ; cash rents rise to as much as Rs. 50 per acre, and holdings as small as half an acre are found. Maize is the only crop for which any pains are taken to select the best seed. Advances under the Land Improvement Loans Act are little sought after ; in many places unbricked wells, dug at a trifling cost, answer every purpose, while in others the water lies too deep for masonry wells to be profitable. Even in the Sirwal tract, where there is a tendency to increase the number of masonry wells, they are more often dug in combination by a large number of subscribers, who each own a small holding, than by means of loans from Government.

The cattle are mostly small and weak, especially in the hills, and such good bullocks as are to be found are imported. Although Bajwara and Tihara are mentioned in the Ai)t-i-Akbari as famous for their horses, the breed now found is very poor. The District board maintains two pony and five donkey stallions. The people possess few sheep. Goats, which used to be grazed in the Siwaliks in large numbers, and caused much damage, have now under the provisions of the Chos Act been excluded from the western slopes of that range. Camels are kept in a few villages. A good deal of poultry is bred for the Simla market.

Of the total area cultivated in 1903-4, 91 square miles, or 8 per cent., were clsssed as irrigated. Of this, 57 square miles, or 63 per cent., were irrigated from wells ; 23 square miles, or 25 per cent., from canals; and 11 square miles, or 12 per cent., from streams. There were 6,533 masonry wells and 7,511 unbricked wells, lever wells, and water-lifts. Except lever wells (which are worked by hand), these are worked by bullocks, generally with the Persian wheel, but occasionally with the rope and bucket. They are found chiefly in the Sirwal tract. Canal-irrigation is mainly from a private canal called the Shah Nahr, an inundation cut taking off from the Beas in the north-west of the District. It was originally constructed during the decline of the Mughal empire, and was reojiened in 1846 by a number of local landholders at their own expense. Government in 1 890 acquired by agreement the management of the canal, subject to certain rights reserved to the share- holders. There are also some small cuts taking off from the Beas, which belong to private individuals and villages, and irrigate about 10 square miles. The irrigation from streams is by means of artificial watercourses, and is employed in some of the hilly tracts.

The District has 27 square miles of ' reserved ' and 139 of unclassed forests under the Forest department, consisting of the forests of chll pine which cover the slopes of the Sola Singhi range, and 10 square miles of bamboo forest in the Siwaliks. A small rakh of 3 square miles on the Outer Siwaliks is under the control of the Deputy-Commissioner. All the chll trees on these hills are also the property of Government. The inner slopes are sparsely clad with pine ; the denudation of the outer slopes by the action of the hill torrents has already been referred to. In 1903-4 the forest revenue was Rs. 19,000.

Gold is washed in the bed of the Sohan and other hill streams, but in quite insignificant quantities, the average earnings of the workers not amounting to more than 3 annas a day. The District contains quarries of limestone of some value, and kankar of an inferior quality is found. Saltpetre is extracted from saline earth in fourteen villages, the output being about 140 maunds a year. There are some valuable quarries of sandstone.

Trade and Communication

The principal manufacture is that of cotton fabrics, which in 190 1 employed 44,000 persons. The chief articles are coloured turbans and cloth with coloured stripes. Hoshiarpur Town is a centre for the manufacture of ivory or bone and copper mlay work and of decorative furniture, but the demand for inferior work in E^urope and America has led to deterioration. Lacquered wooden ware and silver-work, with some ivory-carving, are also produced. The carpenters have a reputation for good work, and there is a considerable manufacture of glass bangles. Ornamented shoes are also made, and buskins, breeches, and coats of soft sdmhar (deer) skin. At Dasuva cups and glasses of coloured glass are made. Light 'paper' pottery is made at Tanda, and brass vessels at Bahadurpur.

Trade is chiefly confined lo the ex{)ort of raw materials, including rice, gram, barley, sugar, hemp, safiflower, fibres, tobacco, indigo, cotton, lac, and a small quantity of wheat. Of these, sugar forms by far the most important item. The cane grows in various portions of the plains, and sugar is refined in the larger towns and exported to all parts of the Punjab, especially to Amritsar. The principal imports are cotton piece- goods from Delhi and Amritsar, millets and other coarse grains from the south of the Sutlej, and cattle from Amritsar and the south.

Administration

The District contains no railways, l)ut a line from Jullundur to Hoshiarpur is contemplated. The road from Jullundur to Kangra runs across the District, and transversely to this iwo lines of mad, one on either side of the Siwaliks, carry the submontane traffic between the Beas and Sutlej. The total length of metalled roads is 37 miles, and of unmetalled roads 737 miles. Of these, 21 miles of metalled and 28 miles of unmetalled roads are under the Public Works department, and the rest under the District board. The Sutlej is navigable below Rupar during the summer months, and the Beas during the same period from the point where it enters the District. The Sutlej is crossed by six and the Beas by ten ferries, nine of which are managed by the District board.

None of the famines which have visited the Punjab since annexation affected Hoshiarpur at all seriously ; the rainfall is generally so plentiful and the soil so moist that a great part of the District is practically secure from drought. The area of crops matured in the famine year 1899-1900 amounted to 7-6 per cent, of the normal.

The District is in charge of a Deputy-Commissioner, aided by five Assistant or Extra-Assistant Commissioners, of whom one is in charge of the District treasury. For general administrative purposes the District is divided into four tahsils — Hoshiarpur, Garhshankar, Una, and Dasuva— each with iTahsildar and a naib-Tahsilddr.

The Deputy-Commissioner as District Magistrate is responsible for criminal justice, and civil judicial work is under a District Judge. Both officers are supervised by the Divisional Judge of the Hoshiarpur Civil Division. There are six Munsifs, three at head-quarters and one at each outlying Tahsil. The predominant form of crime is burglary.

Under Sikh rule the District was unusually fortunate, in that Misr Rup Lai was appointed to the administration of the dodb in 1802. He was able and honest, allied to local families by marriage, and interested in the welfare of the people. His assessments were light and easily paid. In 1839 he was succeeded by a different type of ruler, Shaikh Ghulam Muhl-ud-din, whose oppressive administration lasted until the British conquest. The summary settlement of the whole dodb was promptly made on annexation by John Lawrence. The demand was i3-| lakhs. Except in Garhshankar, the summary settlement worked well. In 1846 the regular settlement of Jullundur and Hoshiarpur began. Changes in officers and the pressure of other work prevented anything being done until 1851, when a Settlement officer was appointed to Hoshiarpur. His charge, however, did not correspond with the present District, as other officers settled the Una Tahsil, part of Garh- shankar, and the Mukerian tract. The result for the District as now constituted was an increased demand of Rs. 9,000. Many assignments of revenue, however, had in the meantime been resumed, and the assessment 'was really lighter than the summary demand. Between 1869 and 1873 a revision of the records-of-rights in the hilly tracts was carried out. The settlement was revised between 1879 and 18S2.

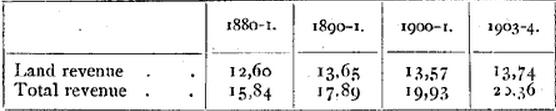

The total revenue assessed was 13^ lakhs, of which Rs. 71,000 are 'assigned,' while a water rate was imposed on the lands irrigated by the Shah Nahr Canal. Government subsequently took over the canal, and the shareholders became annuitants, receiving 8 annas out of every 18 annas imposed as water rate. The canal is managed by the Deputy- Commissioner, and all profits are ear-marked to the improvement and extension of the watercourses. The average assessment on ' dry ' land is Rs. 1-15 (maximum Rs. 4-4, minimum 6 annas), and that on 'wet' land Rs. 4-8 (minimum Rs. 6, minimum Rs. 3). The demand for 1903-4, including cesses, was 16-4 lakhs. The average size of a proprietary holding is 1-5 acres.

The collections of land revenue alone and of total revenue are shown below, in thousands of rupees : —

The District possesses nine municipalities, Hoshiarpur, Tanda- Urmar, Hariana, Garhdiwala, Una, Anandpur, Mukerian, Dasuya, and Miani ; and one ' notified area,' Khanpur. Outside these, local affairs are managed by the District board, which in 1903-4 had an income of Rs. 1,67,000. The expenditure in the same year was Rs. 1,49,000, education being the largest item.

The regular police force consists of 480 of all ranks, including 93 municipal police. The Superintendent usually has three inspectors under him. The village watchmen number 1,765. There are 15 police stations and 4 road-posts. The District jail at head-quarters has accommodation for 106 prisoners.

The District stands twelfth among the twenty-eight Districts of the Province in respect of the literacy of its population. In 1901 the proportion of literate persons was 4 per cent. (7-3 males and 0-2 females). The number of pu[)ils under instruction was 4,813 in 1880-1, 9,749 in 1890 I, 9,639 in 1900-1, and 10,772 in 1903-4. In the last year the District had 13 secondary and 146 primary (public) schools, and 3 advanced and 75 elementary (private) schools, with 278 girls in the public and 315 in the private schools. The Hoshiarpur municipal high school was founded in 1848 to teach Persian and Hindi, and was brought under the Educational depart- ment in 1856. The study of English was introduced in 1859, Arabic and Sanskrit in 1870, at about which time it was made a high school.

There are also three unaided Anglo-vernacular high schools, one ver- nacular high school, and eight middle schocjjs. The Ludhiana Missiriii supports a girls' orphanage and boarding-school, and two day-schools for Hindu and Muhammadan girls. The total number of pupils in public institutions in 1904 was about 7 per cent, of the number of children of school-going age. The total expenditure on education in 1903-4 was Rs. 74,000, the greater part of which was met from Local funds.

The civil hospital at Hoshiarpur has accommodation for 33 male and 12 female in-patients. The District also contains fourteen out- lying dispensaries. At these institutions in 1904 a total of 145,455 out-patients and 1,170 in-patients were treated, and 9,267 operations were performed. Local funds contribute nearly three-fourths of the expenditure, which in 1904 amounted to Rs. 24,000, and municipal bodies the remaining fourth. The Ludhiana Mission has recently opened a female hospital in Hoshiarpur under a qualified lady doctor.

The number of successful vaccinations in 1903-4 was 29,000, representing 29 per 1,000 of the population.

[H. A. Rose, District Gazetteer (1904); J. A. L. Montgomery, Settlement Report (1885).]