Ice cream (business): India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The state of the business

2014-2019; early 2020

John Sarkar, Ice cream cos start home delivery as sales dive 40%, May 29, 2020: The Times of India

From: John Sarkar, Ice cream cos start home delivery as sales dive 40%, May 29, 2020: The Times of India

The Indian ice cream industry has been hit so hard that major companies from Hindustan Unilever (HUL) to Mother Dairy have started delivering the frozen dessert to consumers’ homes to make up for lost ground.

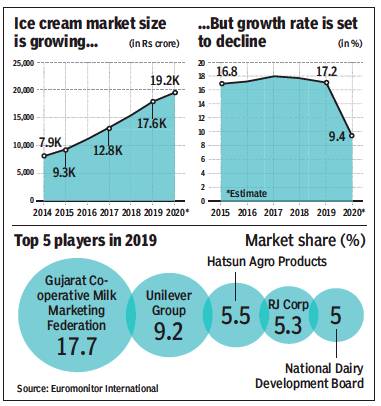

The industry, which was pegged at around Rs 17,639 crore in 2019 by Euromonitor, has lost a major chunk of its yearly sales due to the Covid-19 imposed lockdown and the absence of migrant workers, who man ice cream carts in several markets across the country.

“Around 40% of our yearly ice cream sales are gone, as 60% take place during four months of the year beginning March,” said R S Sodhi, MD of Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation, India’s largest ice cream maker that sells products under the Amul brand name.

While Amul has started delivering ice cream in bulk to Residents’ Welfare Associations, India’s second-largest player HUL, too, has followed in its rival’s footsteps. “As a result of the lockdown, our out-of-home channel remains closed. This has resulted in sharp deceleration in some of the discretionary categories such as ice cream. While manufacturing is continuing in limited capacity, sales continue to be low,” an HUL spokesperson told.

Apart from being available in neighbourhood stores, HUL’s Kwality Wall’s is active on food and grocery delivery services, including Swiggy, Bigbasket and Dunzo. The company has also started delivering ice creams directly to consumers, including sending ice cream trucks to housing societies. “But online sales are just a minuscule portion for ice cream players,” said Rajesh Gandhi, MD of Vadilal and president of the The Indian Ice Cream Manufacturers’ Association. “Sales are currently 20% of what they were last year. Most small ice cream makers have shut shop and others, who stocked up on inventory in the beginning of March, are finding it tough to sell.”

“We only have presence in malls that are still shut. For us, the impact has been huge,” said a former senior executive at premium Swiss icecream Movenpick.

In North India, where ice cream carts play a major role, companies have started delivering directly to consumers. Mother Dairy, for instance, is working with distributors to allow consumers to order directly from its website. Ravi Jaipuria-led Devyani Food Industries, which sells ice cream under the Creambell franchise, recently consolidated its operations.

“We have shut one of the smaller plants at Baddi to strengthen our larger ones,” said Jaipuria, who is also the chairman of Varun Beverages, PepsiCo’s second-biggest bottler. “The company also did not entirely let go of the people who man its ice cream carts. We had urged them to stay during the lockdown.”

Boutique ice creams

2020

Varuni Khosla, February 15, 2021: The Times of India

From: Varuni Khosla, February 15, 2021: The Times of India

From: Varuni Khosla, February 15, 2021: The Times of India

From: Varuni Khosla, February 15, 2021: The Times of India

From: Varuni Khosla, February 15, 2021: The Times of India

Anant Verma was faced with tough choices when the pandemic hit his three-year-old premium ice cream business, Emoi, in Delhi. He had to find more customers for the creamy, gelato-style ice creams or wind down. Luckily, the winds turned favourable in August. The business not only went direct-to-ice cream gourmands via its own website but also started selling through more than 100 retail stores. Emoi even found its way into BigBasket, 24Seven and several other big-ticket frozen food aisles.

Soon enough, online orders also started pouring in — from corporate houses that wanted to boost the morale of employees stuck at home as well as customers who simply wanted to indulge themselves. Verma sold close to one lakh litres in calendar year 2020: a sizable amount, considering this is a premium clean label offering in the ice cream space.

Verma’s story rings true across the premium ice cream segment. The niche segment has suddenly seen a rise in sales, especially after the lockdown began. The reasons for the spike in business vary from seller to seller. Some say they have noticed a change in buying behaviour, leading to more sales.

Many attribute it to a sudden rise in potential buyers staying at home during the pandemic and using social media like never before — a lot of these ice cream makers use social media to expand their reach. No matter the reason, players in the category are happy they have an opportunity to boost visibility and revenues of a product that is sometimes eclipsed by big brands.

Premium ice creams sit at the top of the frozen dessert pyramid. The market is largely niche for these products — usually high in fat with indulgent creamy flavours. They also have a low overrun — the percentage of air mixed in the product during the freezing process. The lower the overrun, the better the quality of ice cream. That is not the only difference. “After you’ve stopped eating it, you should have some cream or fat left on your palate,” says Gaurav Jagiasi, founder of family-run Bay Cream.

Many ice cream entrepreneurs like Verma and Jagiasi say they have been able to rapidly expand their business during the pandemic. Several of these businesses also took this time to expand from being purely business-to-business (B2B) sellers to direct-to-home brands. Verma says the main reason for their success is that premium ice creams are denser and creamier. “We make them in batch freezers while all big brands use continuous freezers that produce endless ice creams (or frozen desserts) without interruption and incorporate a lot of air in the products. A commercial brand of ice cream has about 80-100% overrun. We, on the other hand, use Italian gelato machines and are 100% pure dairy — premium ice creams have 15-25% overrun in comparison,” says Verma.

For 2021-2022, Emoi expects to generate a revenue of Rs 6 crore, doubling its turnover from 2019.

Bigger companies cut costs by loading their products with vegetable oils, sugar, artificial flavours and emulsifiers. Premium businesses tend to stay away from such tactics and bank on the fact that customers know why these ice creams cost more.

Aditya Tripathi’s Cold Love, which retails in Delhi and Jodhpur, is also betting on a promising 2021. The business, which began selling direct to customers in 2020, also managed to raise a little over Rs 1 crore in funding at a valuation of Rs 10 crore from fans of the brand. Its founder is now looking to expand a mixed retail strategy of direct and franchised retail parlours. The company’s revenue, Tripathi says, has grown sharply, selling as much as 5.5x in August over March. While Tripathi says the business is too nascent to talk about the 2020 turnover, he expects the business to grow to Rs 2.5-3 crore in turnover by 2021-22.

Most entrepreneurs were not keen to share their revenue numbers for 2020.

Samir Kuckreja, founder and CEO of boutique food consultancy Tasanaya Hospitality, says the artisanal ice cream segment has evolved and there are many new local players in several cities. This is also because it is a healthy margin business and has found a strong customer demand — margins can range from 35-75%, say industry insiders. Kuckreja says: “From a price perspective, these ice creams typically compare to brands like Haagen Dazs, but are handcrafted in small batches, much like how Ben & Jerry’s began in the US.”

The consultant himself has invested in Cold Love. He says the brand was able to significantly increase visibility and revenues due to focused digital marketing during the lockdown.

It also helps that despite the high manufacturing cost and niche market space, premium ice creams are very much a lucrative business.

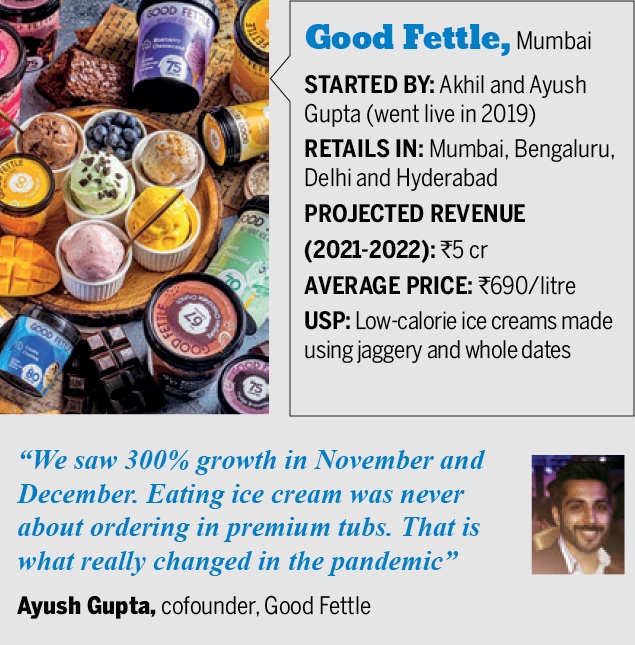

Mumbai-based Good Fettle registered a 300% growth during November and December, say its founders. The hardest part of putting the brand out there, they say, was that it would be a new experience for customers.

Indians were never seen as pint-gobblers when it came to ice cream. It was always associated with a walk or a drive at night with the family or loved ones. Or during a visit to the mall or cinemas. “It hasn’t ever been about ordering in premium tubs. That’s what really changed in the pandemic,” says Ayush Gupta, its cofounder.

A lot of action in the premium ice cream business market seems to be based in Mumbai. Several players have emerged in this city in the last few years.

Gaurav Jagiasi, who runs two-year-old Bay Cream, says they are a family-run business with single-city operation. “In Mumbai, there’s a little bit of competitiveness but it is also mostly hyperlocal, in some sections of the city. We initially never wanted to go straight to the customer. We only wanted to focus on institutions. There was just too much risk in it for a bootstrapped business,” he says. But the pandemic changed all plans.

He and his team started to set up a big part of their consumer business only in January last year. They sold double the quantity in 2020 as compared with 2019. Jagiasi did not disclose actual numbers.

Mumbai-based vegan ice cream brand Nomou, too, shifted its focus from being a B2B retailer to a direct-to-customer one. It sells in 10 cities. “A lot of buildings and societies placed bulk orders,” says Samir Pasad, cofounder of Nomou.

The lockdown made more people open to experimenting with premium brands and that pushed up sales and visibility for such businesses, says these entrepreneurs.

Once the customer likes the taste, Pasad says, price becomes irrelevant. “The pandemic was very good for us because there were limited brands in the market. We were present online directly and there is definitely demand for more premium ice cream products now.” Pasad claims to make a margin of 30%.

The success in Mumbai has encouraged Nomou to expand to Pune, Surat, Goa, Hyderabad, Chennai and Siliguri. It recently signed up with a distributor in Madhya Pradesh too. This growth is impressive when many of the company’s new clients are not even vegan. “They are simply looking for alternatives. They are often healthy eaters and typically between 25 and 40 years,” adds Pasad. The brand uses palm jaggery, which has a low glycemic index and dates to sweeten their ice creams and coconut milk as the base.

Get a Whey — which retails whey protein ice creams with no added sugar — had a similar story. The cofounders of the Mumbai-based company say they saw a sudden increase in sales after the lockdown was announced. Its highest business was in June.

But expansion is not an easy step for these small brands. Lack of good cold chains are still one of the biggest challenges for smaller operators in this space, says Pashmi Shah, cofounder of Get a Whey. “You can’t courier an ice cream yet. Cold chains are very expensive and dry ice and thermocol add to the cost. While ecommerce is at a good stage in India, longer distance deliveries are still challenging. That is why most niche ice cream companies often stay local,” she says.

However, discoverability has become easier now due to social media. “There is a lot of change in customer behaviour in terms of food consumption patterns since the pandemic, and that has given a good push to our business,” she adds.

But infrastructure is not going to come in the way of the unrepentant premium ice cream consumer. “An ice cream is an indulgence, and that is how it should stay,” says Jagiasi. Quite possibly, for these people, every day is a sundae.

Winter business

Till 2022-23

Namrata Singh, April 10, 2023: The Times of India

From: Namrata Singh, April 10, 2023: The Times of India

Are people consuming more ice cream during winter? Ice cream makers say that while summer months still dominate sales, the seasonal variation between hot and cold months is reducing. Typically, sales in winter months fall sharply due to seasonality and reduced incidence of consumers venturing out of their houses. While out-of-home consumption is key for ice cream sales, what's also driving revenue is individual in-home consumption due to quick commerce.

Normally the first six months of the fiscal year can account for 60% of annual sales, or even higher for some brands. Graviss Foods (Baskin Robbins) CEO Mohit Khattar said, over the years, the company has been witnessing relatively stronger performance in the winter months (or the second half of the fiscal year).

"Contribution for the second half of the fiscal year is now up to about 47% from 40% of annual sales. Given the robust growth that we have been witnessing, our average sales in winter months were almost at similar levels as sales in summer months in the 2019-20 (pre-Covid) period," said Khattar.

The trend of ice creams being consumed during off season would be no different for other players, say experts.

Indian Dairy Association president R S Sodhi said, "The seasonal variation in consumption of ice cream is certainly reducing and one of the main reasons is that individual consumption of ice cream at home has gone up due to e-commerce and quick commerce. People also have bigger freezers at home. Additionally, there is a wider choice in flavours today as compared to, say, a decade ago.”

Sodhi, however, said the seasonal variation in the north would still be wider as compared to other regions. "If the ratio of consumption is 1:5 between the peak seasonal months of winter and peak summer in the north, in other regions the same would be 1:2," Sodhi said.

With around 850 stores, Baskin Robbins is the second largest QSR brand in India. Amul, the largest ice cream player, recently said it plans to roll out 100 ice cream parlours in the country, offering premium ice cream flavours.

At an industry level, ice cream is growing at about 17%, said Khattar, with Baskin Robbins growing at a faster pace than the industry. The prime drivers of growth, he said, are the Gen-Z.

"Earlier, ice cream was a relatively reward-driven category. That behaviour is changing now. People like to celebrate their little joys with ice cream. Today, there are multiple occasions for people to consume ice cream, whether it's while binge-watching movies or going out with friends to the multiplex or any other reason.

Occasionally, you see consumption going up. On women's day this year, we suddenly saw a surge in sales," said Khattar.

A closer look at data for women's day revealed that most of the increase was limited to metro cities and to select products like celebration ice cream cakes. Mumbai led the charts with over a 50% increase from the corresponding similar day sales a week earlier. Cities like Bangalore and Delhi did well too. Kolkata was conspicuously behind at 25% growth.