Indian cinema: posters

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Foreign posters of Indian films

Jahan Bakshi’s collection

Mohua Das, January 31, 2021: The Times of India

From: Mohua Das, January 31, 2021: The Times of India

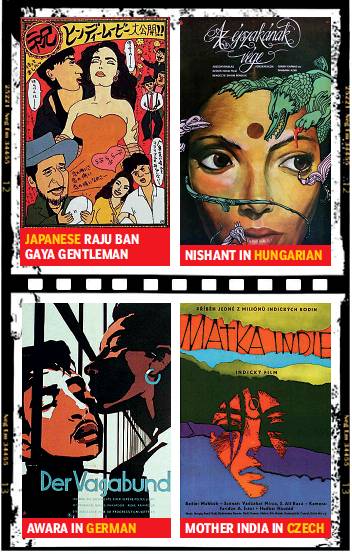

It seems, time travel to an alternate universe may in fact be possible. Only that the time machine isn’t a spinning wheel that disappears in a puff of smoke but comes in the shape of Indian film posters where a Govinda potboiler Gareebon ka Dost inhabits the world of Russian avant-garde, Raj Kapoor’s Jagte Raho finds expression in East German reductive art and Raju Ban Gaya Gentleman is a Japanese manga artist’s muse.

When Jahan Bakshi, a movie art curator in Mumbai, stumbled upon old Czech and British quad posters for Satyajit Ray films with neo-futurist fonts and colourful surrealism, he knew he was onto something special. His curiosity led him down a rabbit hole — of familiar yet outlandish — doppelgangers of Indian movie visuals from across the globe that revealed a fascinating yet undocumented history of how different countries reimagined Indian films.

“Looking for foreign posters of Indian films started as research for an article but soon became an obsession. It was a revelation to see what Indian films look like when seen through a foreign prism,” says Bakshi who has unearthed around 150-odd foreign origin Indian posters and acquired around 50 physical copies from places spanning Russia, Latvia, Bulgaria and East Europe to France, Germany, the UK, US, Japan, China, Thailand and Egypt. “They’re unique both aesthetically and conceptually... like watching an act of translation via a poster image. It was also eyeopening to see just how much Indian cinema had travelled globally in the past.”

If movie posters were the only way to lure audiences into the theatre before trailers came into vogue, marketing Indian films in other countries involved an ingenious sleight of an artist’s hand to adapt them to local aesthetics and culture. Compelling examples from the last seven decades include painterly posters such as Bimal Roy’s 1953 film Do Bigha Zamin where Italian artist Ercole Brini reimagines the canvas of a broken wooden fence and silhouette of a farmer family in watercolours. Hungarian post war artist Herpai Zoltan’s reinterpretation of Shyam Benegal’s Ankur, a 1974 film about the country’s caste system features a hand painted red rose infested with worms instead of a pensive Shabana Azmi.

Recast, often dramatically, to resonate in the local market, these foreign posters blend local language, sexual allure, religion, violence and intellectualism. If some are reminiscent of the myths and legends of that land — for instance, the Russian poster for 1990 action thriller Khoon Bhari Maang borders on a folktale with the magnified head of an alligator occupying centrestage against an intense pink background and the Hungarian reincarnation of Benegal’s Nishant has little dragons wrapped around Azmi’s face — many are visual time capsules indicative of the prevailing politics and censorship in the country.

“The socialist theme of films like Awara and Do Bigha Zamin resonated with audiences in the Soviet Union and across the Eastern Bloc countries. After Mithun Chakraborty became a breakout star in Russia with Disco Dancer, a lot of masala potboilers from the 80s and 90s were released in Russia and visuals of their posters are a sight to behold — symbolic, esoteric and very avantgarde,” says Bakshi.

More recently, Chinese posters for Andhadhun — a massive success collecting over $35 million at the box office in China — took on a darker shade with black and white overtones and a braille piano in the foreground as opposed to the popping colours and quirky vibe of the Indian version.

“Interesting patterns emerge from posters of other countries, too. The US posters tend to be text heavy with emphasis on captions and pull-quotes. Posters from Europe and Central Asia are surprisingly flamboyant, eccentric and at times exoticize Indian-ness. Japanese posters are bizarrely unpredictable varying from subtle to whimsical, gonzo to pulpy,” observes Bakshi who scours popular poster sites like New York’s Posteritati Gallery to obscure ones in Germany, Czech Republic and Japan in his rescue mission though the pandemic did delay some of his packages.

But he is fortunate to have found an ally — the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The 30-year-old who had started ‘Posterphilia’ — a hobby project of posting his favourite movie posters on social media two years ago — drew the attention of Anne Coco, the head of graphic arts collections at the Oscars library, last September. “She approached me, asking if I could help build their collection of Indian film posters which was quite scant,” recounts Bakshi, who over the past few months of sourcing Indian film posters for the Academy, pitched the idea of “also” exploring their foreign counterparts.

“Since then I’ve helped them acquire a bunch of Ray, Raj Kapoor and V Shantaram posters of foreign origin and hope we can build it up further,” he says with his fingers crossed. “Old movie posters are cultural artefacts and I want to reclaim this aspect of Indian film history,” he signs off.