Indore State , 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Indore State

{Indur). — Native State in the Central India Agency, under the Resident at Indore, lying between 21° 22' and 26° 3' N. and 74° 30' and 78° 51' E., with an area of 9,500 square miles, including the isolated pargana of Nandwas or Nandwai (area 36 square miles), which lies geographically in Rajputana. It is bounded on the north by Gwalior State ; on the east by the States of Dewas and Dhar and the Nimar District of the Central Provinces ; on the south by the Khandesh District of the Bombay Presidency ; and on the west by the States of BarwanT and Dhar. The State takes its name from its capital, originally the small village of Indreshwar or Indore, which was first raised to a place of importance in the eighteenth century, and after 18 1 8 became the permanent seat of the Holkar family.

Physical aspects

The State is formed of several detached tracts, of which the largest and most compact lies south of the Narbada river. These tracts may be conveniently divided into two main sections, which correspond to the natural divisions of the aspects plateau and the hilly tract. The plateau section comprises the portion which lies in Malwa proper, and is included in the Rampura-Bhanpura, Mehidpur, and Indore districts. The country in this section, except for the range lying north of Rampura and some scattered hills in the Mehidpur district and Petlawad par- gana, is typical of Malwa generally. The hilly tract, which comprises the Nimar and Nemawar districts, lies partly on and partly south of the great Vindhyan scarp, the Nimar district including also a portion of the Satpura range. The plateau section has an area of 4,320 square miles, the hilly tract an area of 5,143 square miles. Besides these two sections, the small isolated /^r^a;w of Alampur in Bundelkhand, with an area of 37 square miles, owes its existence solely to the presence in it of the cenotaph of Malhar Rao Holkar. The great Vindhyan range, which almost bisects the State, determines its watershed. All the streams north of this barrier flow towards the Jumna-Ganges doab, the chief stream being the Chambal, with its tributaries, the Sipra and lesser and greater Kali Sind. To the south of the Vindhyas lies the Narbada river, with its numerous tributaries.

Very little is known concerning the geology of the territories that By Mr. E. Vredenburg, tieological Survey of India. constitute Holkar's dominions. The principal rock in Malwfi is Deccan trap, weathering superficially into the black soil to which the region owes its great fertility. Near Rampura, east of Nimach, Vin- dhyan rocks of both upper and lower series are exposed, in addition to the Deccan trap. The districts south of the Narbada, largely occupied by the northern spurs of the Satpura Hills, consist principally of Deccan trap. North of the Narbada, the denudation of the Deccan trap has proceeded far enough to bring into view an interesting sequence of the underlying rocks, including gneiss, Bijawars, and Lametas. Gneiss occupies a large portion of the Nemawar district, being overlaid, north of Chandgarh, by Bijawar and Vindhyan strata. Between Katkuf and the Kanar river and at other places near Barwaha, peculiar fault breccias occur either within the Bijawar outcrop, or separating the Bijawars from the Vindhyans. The matrix of the breccia is usually siliceous, but often contains a large admixture of hematite. Strata belonging to the Lameta or infra-trappean group cover a large area around Katkiit. They are mostly sandstones underlaid by conglomer- ates. Round Katkut the Lameta beds are unfossiliferous and probably of fresh-water origin ; but north of Barwaha, at the Ghatia quarries, the conglomerate underlying the sandstone contains marine fossils identical with those found in the cretaceous limestones east of Bagh known as the Bagh beds. The exposure at the Ghatia quarry marks the eastern- most limit reached by the sea in which the Bagh beds were deposited.

The Lameta group contains excellent building stones. The sand- stone quarries at Ghatia north of Barwaha, and those situated on the banks of the Kanar river, east of Katkut, have supplied a great deal of the material used for constructing the Holkar State Railway. One of the limestones is a rock made up of fragments of marine organisms resembling corals, known for that reason as coralline limestone. It constitutes a stone of great beauty, which has been largely used in the ancient buildings of Mandu, for which it was obtained from the old quarries near Chirakhan. This locality has been famous geologi- cally since 1856, owing to the discovery there by Colonel Keatinge of the Cretaceous fossils which settled the age of the Bagh beds.

The low rocky hills of northern Indore often bear a stunted jungle containing Biitea frondosa, Acacia arabica, A. Catechu, and A. leiicophloea, and many shrubs, such as species of Greivia, Ztzyphus, Capparis, Carissa, and Tamarix. In places where the forest is taller, the leading species are Botnbax maiabaricuni, Sterculia urens, Ano- geissus latifolia and A. pendula, Dichrostachys, Frosopis, and species of Cordia. Farther south are tracts with principally salai {Boswellia serrata) and a thin scrub jungle of Fliieggea, Phyllanihus, A/itidesiiia, and similar shrubs. Still farther south occur typical forests of the Central Indian highland class, with icak, sd; (Ten/ii'/ia/ia tomentosa'), tendu (^Diospyros tomentosa), black-wood {Da/hergia latiffllia), tinis {Ougeinia dalbergioides), anjan {Hardwickia binata), and similar species.

All the ordinary wild animals are met with, including tigers, leopards, bears, hyenas, sdjubar, chltal, and antelope. Bison {Bos gaurus and wild buffalo [Bubahis ami) were formerly plentiful in the Satpura region, but are now almost, if not quite, extinct. In the Mughal period elephants were caught in the Bijagarh and Satwas forests. Small game is plentiful throughout the State.

The climate in Malwa is temperate ; the temperature varies in the hot season from 46° to 110° and in the cold season from 40° to go°. In the districts south of the Vindhyan scarp, however, much higher temperatures are met with, while the cold season is of short duration. The annual rainfall on the plateau area averages 30 inches, and in the hilly tract 40 inches.

History

The Holkars belong to the Dhangar or shepherd caste. Their ancestors are said to have migrated southwards to the Deccan from the region round Muttra, and to have settled at the village of Hal or Hoi on the Nira river, 40 miles from Poona, whence they take their family name. Malhar Rao Holkar, the founder of the house of Indore, was born in 1694, being the only son of Khandoji, a simple peasant. On the death of his father, he and his mother went to live in Khandesh with NarayanjI, his mother's brother, a man of some property, who maintained a body of horse for his overlord Sardar Kadam Bande. Malhar Rao was enrolled in this body of horse, and at the same time married his uncle's daughter, Gautama Bai. His soldierly qualities rapidly brought him to the front, and attracted the notice of the Peshwa, who in 1724 took him into his service and gave him the command of 500 horse. Sardar Kadam was delighted at the young man's prowess, and permitted him to assume and fly at the head of his body of horse the banner of the Bande family, a triangular red and white striped flag, to this day the ensign of the Holkar house. In 1728 he received a grant of 12 districts in Malwa, increased to 82 in 1731.

Previous to this he had acquired land south of the Narbada, including the town of Maheshwar, which practically remained the capital of the Holkar dominions until 18 18, as Indore, acquired in 1733, did not become the real administrative capital until after the Treaty of Mandasor. Malhar Rao at this time possessed territory yielding an income of 74^ lakhs a year, the Peshwa honouring him with the title of Si/bahddr of Malwa. He was con- tinually employed in the Peshwa's conquests, against the Nizam (1738), the Portuguese at Bassein (1739), and the Rohillas (1751) ; and his influence and possessions increased rapidly. In 1761 came the disastrous battle of Panipat, which broke the Maratha power for a time. Thus Malhar Rao, from being the son of a small peasant, had become at sixty-seven the holder of vast territories stretching from the Deccan to the Ganges. After the flight from PanTpat, he proceeded to establish and consolidate his power in his possessions. Death, however, overtook him suddenly at Alampur on May 2, 1766. Malhar Rao was primarily a soldier, and in no way the equal of his contemporary Mahadji Sindhia as a politician ; but his courage was unsurpassed, and his disregard of money proverbial. He had one son, Khande Rao, who was killed in 1754. Khande Rao's son, Male Rao, was a boy of weak intellect. He was allowed to succeed, but soon showed by his excesses that he was unfit to rule, and died a raving madman in 1767. His mother, Ahalya Bai, refused to adopt an heir and personally assumed charge of the administration of the State. The Peshwa's uncle, Raghuba, who was then in Central India, wished to compel her to adopt ; but Mahadji Sindhia supported Ahalya Bai, and her position was at length recognized. She selected Tukoji Rao Holkar, a member of the same clan but not related to the ruling family, to bear titular honours and command her armies. He was a simple soldier, and served Ahalya Bai with unswerving loyalty until her death.

The administration of Ahalya Bai is still looked upon in Central India as that of a model ruler. Her toleration, justice, and careful management of all the departments of the State were soon shown in the increased prosperity of her dominions, and the peace which ruled throughout her days. Her charities, which extended all over India, and include buildings at Badrlnalh, Gaya, and Rameswaram, are pro- verbial. It was during her rule that the Holkar Darbar first employed regular battalions under Chevalier Dudrenec, Boyd, and others.

On the death of Ahalya Bai in 1795, Tukoji Rao succeeded. Mahadji Sindhia had died in 1794, and Tukoji, now seventy years of age, was looked up to as the leading Maratha chief. He followed in the steps of Ahalya Bai, and during his life the prosperity of the State continued. Politically, he acted as a check on the youthful and warlike Daulat Rao Sindhia, which went far to secure general tranquil- lity ; but he died in 1797, and confusion at once followed. Tukoji Rao left two legitimate sons, Kashi Rao and Malhar Rao ; and two illegitimate sons, Jaswant Rao and Vithoji. Kashi Rao was of weak intellect, and Malhar Rao had attempted to be recognized by Tukoji as successor. Failing to attain his desire, Malhar Rao threw himself on the protection of Nana Farnavis. Kashi Rao then appealed to Daulat Rao Sindhia, who at once seized this opportunity of becoming practically the manager of the Holkar estates, and Malhar Rao was attacked and killed. From this disaster, Jaswant Rao and Vithoji escaped.

The former, after a fugitive life spent partly as a prisoner at Nagpur and partly at Dhar, managed at length to raise a force and appeared as the champion of Khandc Rao, a posthumous son of Malhar Rao, being joined in 1798 by Anilr Khan (afterwards Nawab of Tonk). Kashi Rao's troops under Dudrenec were defeated at Kasrawad, whereupon Dudrenec transferred his allegiance and his battalions to Jaswant Rao, who entered the capital town of Maheshwar and seized the treasury there. Soon afterwards, however, he was defeated at Satwas by some of Sindhia's battalions and retired on Indore, but subsequently attacked Ujjain, extracting a large sum from its inhabitants. In October, 1801, Sarje Rao Ghatke, the notorious minister of Daulat Rao Sindhia, sacked Indore, practising every kind of atrocity on the inhabitants and razing the town to the ground.

Jaswant Rao, however, assisted by Amir Khan and his Pindaris, then proceeded to scour the country from the Jumna to the Nizam's terri- tories. By 1802 he had regained his prestige, and so increased his forces as to be able to attack the Peshwa at Poona. This defeat drove the Peshwa to sign the Treaty of Bassein with the British, and Jaswant Rao was forced to retire to Malwa. He held aloof during the war of 1803 against Sindhia, possibly in hopes of aggrandizing himself at that chiefs expense. But in 1804, after rejecting all offers of negotiation, he finally came into collision with the British forces. In the Mukan- dwara pass he gained a temporary success over Colonel Monson, but was defeated by Lord Lake at Dig (November, 1804). In December, 1805, he was driven to sign the Treaty of Rajpurghat on the banks of the Beas river, the first engagement entered into between the British Government and the house of Holkar.

By this treaty he ceded much land in Rajputana, but received back certain of his former possessions in the Deccan, while the country round Kunch in Bundelkhand was granted in jaglr to his daughter, Bhima Bai, who was married to (iovind Rao Bolia. Lord Cornwallis's policy of non-interference, however, gave him another chance ; the Rajputana districts were restored to him, and he proceeded to recoup his shattered fortunes by plundering the Rajput chiefs. In 1806 he poisoned Khande Rao and murdered Kashi Rao, and thus became in name, what he had long been in fact, the head of the house of Holkar. He began at this time to show signs of insanity, and died a raving lunatic at l>hanpura in iSii.

Jaswant Rao left no legitimate heirs; but before his death, Tulsi Bai, his concubine, a woman of remarkable beauty and superior education, had adopted his illegitimate son, Malhar Rao, who was j)laccd on the gaddi, Zalim Singh of Kotah coming to Bhanpura to pay the homage due from a feudatory to his suzerain. After Jaswant Rao's death the State rapidly became involved in difficulties. Revenue was collected at the sword's point indiscriminately from Sindhia's, the Ponwar's, or even Holkar's own territories. There was in fact no real administration, its place being taken by a mere wandering and predatory court, presided over by a woman whose profligate ways disgusted even her not too particular associates. Plot and anarchy were rife. Tulsi Bai was personally desirous of making terms with the British, but was seized and murdered by her troops, and things rapidly grew from bad to worse.

On the outbreak of the war in 1817 between the British and the Peshwa the Indore Darbar assumed a hostile attitude. The defeat, however, of the State forces by Sir Thomas Hislop's division at Mehidpur compelled Holkar to come to terms ; and on January 6, 1 81 8, he signed the Treaty of INIandasor, which still governs the relations existing between the State and the British Government. By this agreement Amir Khan was recognized as an independent chief, all claims on the Rajputana chiefs were abandoned, and all land held by Holkar south of the Narbada was given up, while the British Government undertook to keep up a field force sufficient to protect the territory from aggression and maintain its tranquillity (this force still being represented by the Mhow garrison), the State army was reduced to reasonable proportions, and a contingent force raised at the expense of the State to co-operate with the British when required. Ghafur Khan was recognized as Nawab of Jaora, independent of the Indore Darbar, and a Resident was appointed at Holkar's court.

The immense benefit conferred by this treaty soon became apparent. The State income in 1817 was scarcely 5 lakhs, and even that sum was only extorted by violence, representing rather the gains of a predatory horde than the revenue of an established State. The administration was taken over by Tantia Jogh, who by the time of his death in 1826 had raised the revenue to 27 lakhs, which, added to certain payments made by the British Government and tributary States, brought the total to 30 lakhs. After Tantia Jogh's death, however, things again fell into confusion. Malhar Rao was extravagant and weak, and easily led by favourites. Two insurrections broke out, one, of some importance, being led by HarT Rao Holkar, who, however, surrendered and was imprisoned at Maheshwar (18 19).

Malhar Rao died in 1833 at twenty-eight years of age, and was succeeded by Martand Rao, a boy adopted by the late chief's widow, Gautama Bai. Hari Rao, however, was released from the fort of Maheshwar by his supporters ; and as the adoption of Martand Rao had been made without the knowledge of the British Government, Hari Rao was formally installed by the Resident in April, 1834, Martand Rao receiving a pension. Raja Bhao Phansia, a confirmed drunkard, had been selected as minister and the administration soon fell into confusion, which was added to by the excessive weakness of the chief. Life and property were unsafe, while numerous intrigues were set on foot on behalf of Martand Rao. HarT Rao died in 1843, and was succeeded by Khande Rao, who was half imbecile and died within four months.

The claims of Martand Rao were now again urged, but the British Government declined to sanction his succession. It was then suggested by the Ma Sahiba Kesara Bai, a widow of Jaswant Rao, that the younger son of Bhao Holkar, uncle to Martand Rao, should be chosen, and the youth was installed in 1844 as Tukoji Rao Holkar II. The Regency Council which had held office under the late chief continued, but a close supervision was now maintained by the Resident, and numerous reforms were set on foot. In 1848 the young chief began to take a part in the administration. Kesara Bai, who had been respected by all classes and rendered great assistance to the British authorities, died in 1849. The chief then took a larger share in the government, and showed his aptitude for ruling so rapidly that full powers were granted to him in 1852. In the Mutiny of 1857, Holkar was unable to restrain his troops, who consisted of about 2,000 regular and 4,000 irregular infantry, 2,000 regular and 1,200 irregular cavalry, with 24 guns. The irregular force attacked the Residency, and the Agent to the Governor-General was obliged to retire to Sehore. Holkar personally gave every possible assistance to the authorities at Mhow ; he established regular postal communication, and at consider- able risk protected many Christians in his palace.

In order to make the Indore State more compact, various exchanges of territory were effected between 1861 and 1868, the districts of Satwas in Nemawar, of Barwaha, Dhargaon, Kasrawad, and Mandlesh- war in Nimar being exchanged for land held in the Deccan, the United Provinces, and elsewhere. In 1877, 360 square miles of territory in the Satpura region were transferred to Holkar as an act of grace and to commemorate the assumption by Her Majesty of the title of Empress of India. A postal convention was effected in 1878 and a salt convention in 1880.

In 1860 a sum of more than 3 lakhs was paid to Holkar as compensation for expenses incurred in raising a body of troo[)S in place of the Mehidpur Contingent, which had mutinied ; and in 1865 the contribution to the upkeep of the Mehidpur Contingent and Malwa I>hTl Corps was capitalized. Holkar receives Rs. 25,424 a year in compensation for the Patan district made over to Bundi in 1818, and Rs. 57,874 tribute from the Partabgarh State in Rajputana, both payments being made through The British Government. In 1864 he ceded all land required for railways throughout the State, and in 1869 contributed a crore of rupees towards the construction of the Khandwa-Indore branch of the Rajputana-Malwa Railway, known as the Holkar State Railway. 'I'ukoji Rao was made a G.C.S.I. in 1861 ; and at the Delhi assemblage on January i, 1877, he was made a Counsellor of the Empress and a CLE. He died in 1886 and was succeeded by his eldest son Sivaji Rao, born in 1859.

On his accession, the Maharaja abolished all transit dues in the State. He visited England in 1887 on the occasion of the Jubilee of the Queen-Empress Victoria, when he was made a (j. C.S.I. His administration, however, was not a success, and for the better super- ^•ision of so large a State a separate Resident at Indore was appointed in 1899. In 1902 the State coinage was replaced by British currency. In 1903 Sivajf Rao abdicated in favour of his son TukojT Rao III, the present chief, who is a minor, and is studying at the Mayo College at Ajmer. The ex-Maharaja lives in the palace at Barwaha, receiving an allowance of 4 lakhs a year. 'I'he chief bears the titles of His High- ness and Maharaja-dhiraj Raj Rajeshwar Sawai Bahadur, and receives a salute of 19 guns, or 21 guns within the limits of Indore territory.

Besides Dhamnar and Un, there are no places of known archaeo- logical importance in the State. Remains are, however, numerous throughout the Mahva district, being principally Jain and Hindu temples of the tenth to the thirteenth century : in some cases the temples have been built from the ruins of older buildings, as for example at Mori, Indok, Jharda, Makla, and many other places. In the Nimar and Nemawar districts a considerable number of Muham- madan remains are to be met with, while forts are found throughout the State, those at Hinglajgarh, Bijagarh, and Sendhwa being the most important.

Population

There have been three complete enumerations of the State, giving (t88i) 1,054,237, (1891) 1,099,990, and (1901) 850,690. The density in 1 90 1 was 90 persons per scjuare mile, rising in the plateau area to 112 persons, and droppmg m the hilly tract to 69. The population increased by 4 per cent, between 1881 and 1891, but fell by 23 per cent, in the next decade. The decrease is mainly due to the effect of bad seasons, notably the di.sastrous famine of 1899-1900, from which the State had not had time to recover when the latest enumeration was made. The main statistics of population and land revenue are given on the next page.

The chief towns are Indore Citv, Rampura, Kharcjon, Mahksh- WAR, Mehidi^ur, Barwaha, and Bhantura (excluding the British cantonment of Mhow and the civil station of Indore). There are also 3,368^ villages, with an average number (^f 252 inhabitants. Classified by religion, Hindus number 673,107, or 79 per cent.; Animists, 94,047, or 11 per cent. : Musalmans, 68,862, or 8 per cent. ; and Jains, 14,255, or 2 per cent. The principal languages are Mahvi and the allied Nimari and Rangri, spoken by 240,000 persons, or 28 ])er cent. ; and Hindi, spoken by 492,895, or 57 per cent.

The prevailing castes are Rrahmans, 71,000, or 8 per cent. ; Balais, 61,000, or 7 per cent.; Rajputs, 57,000, or 7 per cent.; Chamars, 33,000, or 4 per cent. ; and Gfijars, 28,000, or 3 per cent. About 40 per cent, of the population are supported by agriculture, 23 per cent, by general labour, 10 per cent, by State service, and 5 per cent, by mendicancy. Brahmans and Rajputs are the principal landholders, the cultivators being chiefly Rajputs, Giijars, Sondhias, Khatis, and Kunbis, and in the southern districts Bhilalas.

The Canadian Presbyterian Mission have their head-quarters in the Residency, and also carry on work in Indore city. In 1901 native Christians numbered 91.

Agriculture

The general agricultural conditions vary with the two natural divisions of the State. The plateau section shares in the conditions common to the fertile Malwa plateau, the soil in this region being mainly of the well-known black cotton variety, producing excellent crops of every kind, while the population is composed of industrious cultivators. In the Nimar and Xemawar districts the soil is less fertile, except actually in the Narbada valley, and the rainfall rather lower, while the Bhils, who form the majority of the population, are very indifferent cultivators. In both cases, the success or failure of the crops depends entirely on the rainfall. The classification of soils adopted by the cultivators them- selves is based on the appearance and quality of the soil, its proximity to a village, and its capability for bearing special kinds of crops. The main classes recognized are : miir or kd/i matti, the black cotton s(jil, of which there are several varieties; pili, a light yellow Sf)il; pdiuihar, a white soil, of loose texture ; antharpatha^ a black loamy soil with rock close below it ; and kharai^ a red-coloured stony soil. According to their position and crop-bearing qualities, soils are termed chauras, 'even'; dhalu, 'sloping'; chhapera, 'broken' soil; or rdkJiad, laiul close . to villages. Land bearing rice is called sdlgaita. Only the black soil yields a spring as well as an autumn crop. Manuring is not much resorted to, except in the case of special crops or on land close to villages, where manure is easily procurable. All irrigated land produces as a rule two crops.

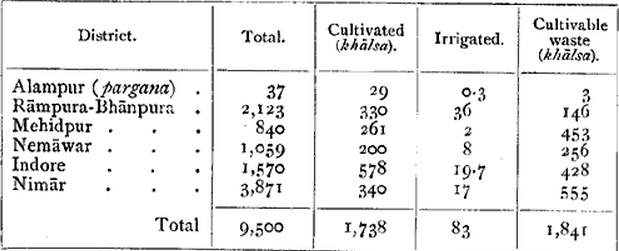

Of the total area of the State, 1,280 square miles, or 12 per cent., have been alienated in grants, leaving 8,220 square miles directly under the State. Of this, 1,738 square miles, or 21 per cent., were culti- vated in 1902-3; 3,000 square miles, or 36 per cent., were forest; 1,841 square miles, or 22 per cent., cultivable but not cultivated; and the rest waste.

The principal statistics of cultivation in 1902-3 are shown in the following table, in square miles : —

The chief autumn crops are, in square miles: cotton {220), Jowar (178), bdjra (93), maize (82), and tuar (38); the chief spring crops are gram (1,021), alsi (143), poppy (35). and wheat (34). The staple food-grains are maize, Jowar, bdjra, wheat, barley, gram, and tuar.

All attempts to introduce new varieties of seed have been hitherto unsuccessful. The State makes liberal allowances in both seed and cash to cultivators in villages managed directly by Darbar ofificers. The advances are repayable at harvest, interest at the rate of 1 2\ per cent, being charged. No interest is charged on cash advances for the purchase of bullocks. In the case of villages farmed out the farmer makes the advances, receiving one and a quarter or one and a half times the amount advanced.

There are two local breeds of cattle, the Malwi and Nimarl. Those of the Malwi breed are medium-sized, generally of a grey, silver-grey, or white colour, and are strong and active. The Nimari breed is much larger than the Malwi, and well adapted to heavy work. These cattle are usually of a broken red and white colour, more rarely all red with white spots. They are bought for military purposes.

Only 5 per cent, of the total cultivated area i.s irrigated, and irrigation is mainly confined to certain crops, such as poppy and sugar-cane, which can only be grown by means of artificial watering. The yellow

soil, which is met with in some quantity in the Rampura-Bhanpura and Ximar districts and in the Petlawad pargafia, requires watering for the production of good crops of all kinds, and irrigation is, therefore, much more common in these districts than elsewhere. Irrigation is usually done from wells by means of a lift. The construction of irrigation works was greatly encouraged by Maharaja Tukojl Rao Holkar II. The wells belong as a rule to private individuals, and tanks and dams to the State ; the latter were formerly under district officers, and have, through neglect, fallen into bad repair. A regular irrigation branch has now been started, and large sums have been sanctioned for the restora- tion of old irrigation works and the construction of new ones. The revenue paid by the cultivators depends on the crop-bearing power of the soil, the possibility of irrigation, and its proximity to a village, which facilitates manuring.

Forests

Forests cover approximately 3,000 square miles. Prior to 1903 they were roughly divided into ' major ' and ' minor ' jungles, controlled respectively by the State Forest department and the district officials. Contractors were permitted to collect forest produce, paying the requisite dues on leaving the forest. An experienced Forest officer has now been put in charge with a view to systematic management. Every facility is given in famine years for the grazing of cattle and collection of jungle produce. In 1902-3 the forest receipts were i-S lakhs, and the expenditure was Rs. 59,000. The forests lie in three belts. In the hilly region north of Rampura- Bhanpura sddad or sdj {Termifm/ia fomefitosa), dhaora {Anogeissi/s laiifolia), lendya {Lagers/roemia parviflora), khair {^Acacia Catechii), and tendu {Diospyros tomentosa) prevail ; on the main line of the Vindhyas north of the Narbada, and also in the country south of that river, including the heavy forest area of the Satpuras, teak, anjan {Hardivickia binata), and salai {Bostvellia serratd) occur.

No mineral deposits of any commercial value are known in the State, although hematite exists in large quantities at Barwaha and was formerly worked. Building stone of good quality is obtained in a few places, the quarries at Ghatia and Katkut being the most important.

Trade and Communication

The manufactures of the State are of little importance, but the cotton fabrics produced at Mahkshwar are well-known. A cotton mill has been in existence in Indore city since 1870, producing coarse cloth, chiefly for local use. The mill was coJmii^ic^a"fons. originally worked by the State, but since 1903 has been leased to a contractor, who also rents the ginning factory and press attached. About 500 hands are employed, wages ranging from 2 to 6 annas a day. A State workshop under the Public Works department was opened in 1905, which undertakes casting and forging, carriage-building, and other work.

A considerable trade is carried on in grain, hemp fibres, cotton, and opium, which are exported to Bombay. The principal imports are European hardware, machinery, piece-goods, kerosene oil, European stores, and wines. The chief trade centres are Indore, Mhow, Barwaha, Sanawad, and Tarana.

The Indore State is traversed by the Khandwa-Ajmer branch of the Rajputana-Mahva Railway. The section from Indore to Khandwa through Mhow cantonment is known as the Holkar State Railway, the Darbar having granted a loan of one crore for its construction. The line crosses the Narbada at the foot of the Vindhyan scarp by a bridge of fourteen spans of 200 feet each. The Ratlam-Godhra branch of the Bombay, Baroda, and Central India Railway passes through the Petlawad fargcwa, and the Bhopal-Ujjain Railway through the Mehidpur district, with a station at Tarana Road. The Nagda-Baran-Muttra line, now under construction, will pass through the ]\Iehidpur and Rampura- Bhanpura districts.

The chief metalled roads are the Agra-Bombay road, of which 80 miles lie in the State ; the Indore-Simrol-Khandwa road, with 50 miles ; and the Mhow-Nimach road, 12 miles in length, all of which are maintained by the British Government. Many new roads are now under construction, by which the territory will be considerably opened out.

A State postal system was first started in 1873 by Sir T. Madhava Rao, when minister to Maharaja TukojT Rao II, and three issues of stamps have been made. In 1878 a convention was made with the British Post Office, by which a mutual exchange of correspondence was arranged. There are also twelve British post offices in the State, through which 157,156 articles paid and unpaid were sent in 1903-4, the total cash receipts being Rs. 72,000.

Famine

The most serious general famine since the formation of the State was that of 1 899- T 900, which visited Malwa with special severity. The distress was enhanced by a succession of bad years,

in which the rainfall had been (1895) 29 inches, (1896) 26 inches, (1897) 30 inches, (1898) 39 inches, and (1899) 10 inches ; and by the inability of the people to cope with a calamity of which they had had no previous experience. Only 37 per cent, of the land revenue demand was realized in 1 899-1900, while prices rose for a time to 100 and even 300 per cent, above the average during the previous five years. Strenuous efforts were made to relieve distress, 15 lakhs being expended from State funds and 3 lakhs from charitable grants, in addition to various works opened as relief works. The disastrous effects were only too apparent in the Census of 1901, while the large number of deserted houses, still to be seen in every village, show even more forcibly the severity of the calamity. The number of

persons who came on relief for one day was 572,317, or more than half

the total population.

Administration

The State is divided for administrative purposes into five zilas or districts — Indore, Mehidpur, Rampura-Bhanpura, Nemawar, and NiMAR — besides the isolated parm}m of Alampur, which is separately managed. Each zila is in charge of a Sfibah, who is the revenue ofificer for his charge and a magistrate of the first class. Subdivisions of the zilas, called pafgatias, are in charge of a/nlns, who are subordinate magistrates and revenue officers and act under the orders of the Subah.

The chief being a minor, the ultimate administrative control is at present vested in the Resident, who is assisted by a minister and a Council of Regency of ten members, who hold office for three years. The minister is the chief executive officer. A special judicial committee of three members deals with appeals and judicial matters, while separate members individually control the judicial, revenue, settlement, finance, and other administrative departments.

The judicial system consists of the Sadr or High (Jourt, presided over by the chief justice with a joint judge, and district and sessions courts subordinate to it. The Sadr Court has power to pass any legal sentence, but the confirmation of the Resident and Council is required for sentences involving death or imprisonment for more than fourteen years. Its original jurisdiction is unlimited ; appeals from It lie to the judicial committee and Council, while all appeals from subordinate courts lie to it. When not a minor, the chief has full powers of life and death over his subjects. Sessions courts can impose sentences of imprisonment up to seven years. The district courts can try cases up to Rs. 1,000 in value. The British codes, and many other Acts modified to suit local requirements, are used in the State. In 1904 the courts disposed of 7,700 original criminal cases and 331 appeals, and 10,763 civil cases and 565 appeals, the value of property in dispute being 1-3 lakhs. The judicial establishment costs about 1-3 lakhs per annum.

The State has a normal revenue of 54 lakhs, of which 38 lakhs are derived from land, 2-7 lakhs from customs, 3-2 lakhs from excise, 1-8 lakhs from forests, and 10 lakhs from interest on (lovernment securities. The chief heads of expenditure are : general adminis- tration (14-6 lakhs), chief's establishment (ii-S lakhs), army (9-7 lakiis), public works (5-8 lakhs), police (3-6 lakhs), law and justice (i-6 lakhs), education (Rs. 82,000), sayar or customs (Rs. 71,000), medical and forests (Rs. 59,900 each).

The State is the sole proprietor of the soil, the cultivators having only the right to occupy as long as they continue to pay the revenue assessed. In a few special cases mortgage and alienation are permissible. Villages may be classed in two groups : k/ia/sa, or those managed directly by the State ; and ijdra, or flirmed villages. Leases of the latter are usually given for five years, the farmer being responsible for the whole of the revenue, less 12^ per cent, commission, of which 2-| per cent, is allowed for working expenses and 10 per cent, as actual profit.

Until 1865 whole pargafias were granted to farmers, a general rate being assessed of Rs. 8 per acre for irrigated and R. i for unirrigated land. In that year a rough survey was completed, on which a fifteen years' settlement was made, the demand being 38 lakhs. A fresh assessment was made in 1881 ; but excessive rates and mismanage- ment rendered it abortive, only about 45 lakhs being realized annually out of a demand of 65 lakhs. The cultivators despaired of paying off their debts and commenced to leave their homes, while the village bankers refused to advance money. For the best black cotton soil, capable of bearing two crops a year, the rates at present range from Rs. 6 to Rs. 56 per acre. Ordinary irrigated land pays from Rs. 3 to Rs. 8 an acre, the average being about Rs. 4, and unirrigated land from a few annas to R. r. In 1900 a detailed survey was com- menced, and a regular settlement was begun in 1904. In that year 38 lakhs were collected out of a demand of 45 lakhs. A consider- able proportion is derived from the high rates paid for land bearing poppy.

Opium is subject to numerous duties. The crude article, called chJk, brought into Indore city for manufacture into opium, pays a tax of Rs. 16 per fnaund. The manufactured article, again, is liable to a complicated series of no less than twenty-four impositions, of which fourteen are connected with satta transactions or bargain-gambling carried on during its sale. The total amount of the impositions, including an export tax of Rs. 13-8-0 on each chest (140 lb.) exported to Bombay, amounts to Rs. 50 per chest. About Rs. 30,000 a year is derived from the registration and control of the saiia transactions. In 1902-3, 4,767 chests of opium were exported, and the total income from duties was about i'8 lakhs.

Salt which has paid the tax in British India is imported for local consumption duty free, under the engagement of 1883, by which the Indore State receives from the British Government Rs. 61,875 per annum in lieu of duties formerly levied.

The excise administration is as yet very imperfect. The out-still and farming systems of British India are followed in different tracts. Liquor is chiefly made from the flowers of the mahud {Bossta latifoHa), which grows plentifully in the State. In 1902-3 the total receipts on account of country liquor were 1-4 lakhs, giving an incidence of r anna 10 pies per head of population.

The State coinage until 1903 consisted of various local issues, including the Hali rupee coined in Indore city. The British rupee became legal tender in June, 1902.

Municipalities are being gradually constituted throughout the State. Besides Indore city, there are now municipalities at fourteen places, the chief of which are Barwaha, Mehidpur, and Tarana.

A State Engineer was appointed in the time of Maharaja Tukojl Rao II, but no regular Public Works department was organized until 1903, It now includes seven divisions, five for district work and two for the city, each division being in charge of a divisional engineer. The department is carrying out a great number of works, including 250 miles of metalled and 40 of unmetalled roads, besides numerous buildings.

The foundation of the Holkar State army was laid in 1792, when Ahalya Bai, following the example of MahadjT Sindhia, engaged the services of Chevalier Dudrenec, a French adventurer, known to natives as Huzilr Beg, to raise four regular battalions. Though these battalions were defeated at Lakheri in 1793 by De Boigne, their excellent fighting qualities led to the raising of six fresh battalions, which two years after took part in the battle of Kardla (1795). In 181 7 Malhar Rao's army consisted of 10,000 infantry, 15,000 horse, and 100 field guns, besides Pindaris and other irregulars ; but the forces were largely reduced under the Treaty of Mandasor (181 8). In 1887 Holkar raised a regi- ment of Imperial Service cavalry, which in 1902 was converted into a transport corps with a cavalry escort. The State army at present consists of 210 artillerymen with 18 serviceable guns, 800 cavalry, and 748 infantry. The transport corps is composed of 200 carts, with 300 ponies and an escort of 200 cavalry.

The policing of the State was formerly carried out by a special force detached from the State army, which consisted of three regiments of irregular infentry, a body of 1,100 irregular horse, a mule battery, and a bullock battery. In 1902 a regular police force was organized, which now consists of an Inspector-General with the administrative staff and ro inspectors, 50 sub-inspectors, 2,135 constables and head constables, and 140 mounted police with i risdldar. The State is divided into seven police districts — Alampur, Rampura, Bhanpura, Mehidpur, Khar- gon, Indore, and Mandleshwar — each under a district inspector. The number of rural police or chaiikiddrs is based on the village area, at the ratio of one chauklddr to each village of 40 to 130 plouglis, two to one of 130 to 190, and six to one of over 260 ploughs.

There were no regular jails in the State before 1875, when Sir T. Madhava Rao built the Central jail in Indore city. In 1878 the manufacture of coarse cotton cloth and other articles was introduced. There are four district jails, one in each zila except Nemawar, the prisoners for this district being sent to the Nimar jail.

In 1 90 1, 5 per cent, of the people (9-4 males and 0-4 females) were able to read and write. The first definite attempt at encouraging education was made in 1843, during the time of Maharaja Harl Rao Holkar, who at the solicitation of the Resident, Sir Claude Wade, assigned a large State dhar??isa/a for a school, at the same time levying a small cess on opium chests passing through the city, the proceeds of which were devoted to its upkeep. Four branches were started, for teaching English, MarathT, Hindi, and Persian, and the institution continued to increase in importance. In 1891 the Holkar College was established, under a European principal. Two boarding-houses were also constructed, which are capable of accommodating 40 students. The College contains on an average 70 students, and is affiliated to the Allahabad University. Scholarships are granted by the State to selected students desirous of pursuing their studies at the Bombay Medical College or elsewhere. Vernacular education in villages was first undertaken in 1865, and 79 schools had been opened by 1868, including 3 for girls. In 1902-3 there were 88 schools for boys with 5,987 pupils, and 3 for girls with 182 pupils.

Till 1850 no steps had been taken by the State to provide medical relief for its subjects. In 1852 Tukojl Rao II, on receiving full powers, made a yearly grant of Rs. 500 to the Indore Charitable Hospital, the Resident at the same time undertaking to maintain a dispensary in Indore city. Soon after, 4 district dispensaries were opened. By 1891, one hospital and 14 dispen.saries had been established, and 34 native Vaidyas and Hakims were employed. There are now 23 district hospitals and dispensaries, and 39 native Vaidyas and Hakims, besides the Central Tukojl Rao Hospital and dispensaries in the city. The total number of cases treated in 1902-3 was 186,479, of which 37,819 were treated in the Tukojl Rao Hospital. A lunatic asylum is super- vised by the jail Superintendent.

Vaccination is carried on regularly, and 7,869 persons, or 9 per 1,000 of the population, were protected in 1902 3.