Infant mortality: India

Please also see the Indpaedia page Infant mortality: South Asia . All reports that mention even one South Asian country in addition to India are archived on the page Infant mortality: South Asia .

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Causes, factors

1990-2017: Malnutrition remains risk factor for 68% child deaths

Sushmi Dey , Sep 19, 2019: The Times of India

From: Sushmi Dey , Sep 19, 2019: The Times of India

Malnutrition continues to be the leading risk factor for deaths in children under five years of age across India causing 68% of mortality in the category, even as the death rate due to malnutrition has dropped by two-third during 1990-2017, according to estimates released by Indian Council of Medical Research.

Data shows malnutrition is also the leading risk factor for health loss in persons of all ages, accounting for 17% of the total DALYs (disability adjusted life years). The DALY rate attributable to malnutrition in children varies sevenfold between states and is highest in Rajasthan, UP, Bihar and Assam, followed by MP, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Nagaland and Tripura.

Among malnutrition indicators, low birth weight is the biggest contributor to child deaths in India, followed by child growth failure which includes stunting, underweight and wasting. The prevalence of low birth weight was 21% in India in 2017, ranging from 9% in Mizoram to 24% in UP.

The findings also highlight rapidly increasing prevalence of child overweight. This annual rate of increase in child overweight between 1990 and 2017 was pegged at 5% in India, which varied from 7.2% in MP to 2.5% in Mizoram. In 2017, the prevalence of such children was 12%. The estimates, part of the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2017, were also published in the Lancet Child & Adolescent Health on Wednesday. The study was conducted by the India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative — a joint initiative of the ICMR, Public Health Foundation of India, and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation in collaboration with health ministry.

Study claims ‘Mortality from severe malnutrition just 1.2%’ (2018?)

Rema Nagarajan, Oct 17, 2019: The Times of India

Mortality from severe acute malnutrition (SAM) might be just 1.2%, much lower than the 10-20% estimated by the World Health Organisation based on older studies largely done in Africa, a study of two tribal districts in Jharkhand and Odisha has found. The findings strengthen the case for prioritising prevention through known health, nutrition, and multisectoral interventions in the first 1,000 days of life and raise doubts on a strategy based on combatting SAM through ready to use therapeutic food (RUTF).

The study done in two poor, rural tribal districts of Jharkhand and Odisha with high levels of child undernutrition included over 2,600 6-month old children and tracked them for 18 months.

The study authors suggested that one of the reasons for low mortality among the SAM-affected children could be because the children studied were six months old while the heaviest toll on children was in the first six months of life, before treatment with RUTF became relevant. In the trial area, 64% of all infant deaths occurred in the first month of life and 86% in the first six months.

This is in keeping with the overall trend in India, where neonatal deaths constitute 58% of under-5 child deaths and neonatal deaths are mostly caused by pre-maturity or low birth weight, noted the study. Pre-maturity and low birth weight reflect chronic undernutrition over generations inflicted by poverty.

One of the authors, Dr HPS Sachdev, told TOI that there were multiple attempts to portray SAM as an acute emergency situation and to show that afflicted children will either die or never recover unless “magic therapeutic food” (RUTF or peanut butter composed food) is provided. “We have busted this myth through two published studies, including the current one, that clearly show that even without any programme for communitybased management of acute malnutrition, mortality in SAM is very low (1.2%-2.7%) over six months to one-year period, and that spontaneous recovery occurs in a substantial proportion,” said Dr Sachdev, adding that current Indian evidence indicated that “the scare-mongering and hysteria” around SAM was unwarranted. “I may be having an extreme paranoid view, but the repeated advocacy for RUTF convinces me of attempts at commercialisation of development misery rather than saving of starving kids,” said Dr Sachdev.

Dr Sachdev pointed out that after 32 weeks of starting RUTF, the recovery rates in the current study without any community-based management were broadly comparable to the rates seen in an earlier trial, which found augmented homemade food as good as RUTF. He explained that there was also the cost argument against a scaled-up use of RUTF as ball park figures suggest the budget needed for it would be equivalent to the entire POSHAN (the government’s nutrition scheme) budget.

Dr Sachdev said while helping severely undernourished children was an imperative, regional home-based food, nutrition counselling, care for illnesses and preventive actions including safe water and sanitation should be a greater priority than focusing on product-based solutions. Prevention Can Work — a recent intervention combining crèches, participatory meetings with women’s groups and home visits — reduced wasting, underweight, and stunting among children under 3 in Jharkhand and Odisha.

Low birthweight, infections

Low birthweight emerges big killer, September 29, 2017: The Times of India

From: Low birthweight emerges big killer, September 29, 2017: The Times of India

See graphic: Mortality rates for newborns by cause of death, 2000-15

Along With Premature Births, It Caused 55% Of Neonatal Deaths In 2015: Lancet

Low birthweight and pre mature births, the top cause of death for new born babies in India, has steadily risen from 12.3 per 1,000 live births in 2000 to 14.3 by 2015. With other major causes of neonatal mortality falling significantly , low birthweight and prematurity accounted for about 55% of all neonatal deaths in 2015 compared to around a quarter in 2000, according to a Lancet study .

Back-of the envelope cal culations show that if the rate of mortality due to babies being born too small or too early had remained the same in 2015 as in 2000, about half a lakh fewer babies would have died that year.

Poor nutrition of mothers, under-age motherhood and inadequate pre-natal care are the major causes for underweight or premature ba bies. Three causes -prematurity or low birthweight, neonatal infections, and birth asphyxia or trauma -accounted for more than three-quarters of neonatal deaths in 2000. Of these, neo natal infections and birth asphyxia or trauma fell dramatically over the next 15 years in both rural and urban areas, rich and poor states.

However, prematurity or low birthweight mortality rates rose in rural areas from 13·2 per 1,000 livebirths in 2000 to 17 in 2015 and in poorer states from 11·3 to 17·8. They fell in urban areas and richer states, but that wasn't enough to offset the damage.

In a clear indication of the effect of maternal malnutrition, the study found that most of the increase in prematurity or low birthweight deaths was happening in babies born at full term but with low birthweight and not in premature babies.

The study was based on data gathered as a part of the ongoing Million Death Study (MDS), in which the Registrar General of India's surveyors do verbal autopsies of the deaths that occurred after the previous census round. A verbal autopsy involves surveyors asking detailed questions on the circumstances in which a death took place.Trained physicians then study these autopsies and assign cause of death. The MDS captured 94,309 child deaths (52,252 neonatal deaths and 42,057 deaths at ages 159 months) from 2001to 2013.

The study observed marked variation in the trends in mortality rates from prematurity or low birthweight, with increases in the rates in Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Bihar, Punjab, and Haryana, but declines in Odisha, Assam and most of the richer states. The study revealed that annual mortality rate declines were faster in under-five children than among newborns.Child mortality rates in India have substantially reduced since 2000, with the steepest decline in 2010-15.

Chances of survival in 1st year

In urban vs. rural areas

2009, 2019

Rema Nagarajan, Oct 31, 2021: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, Oct 31, 2021: The Times of India

Children born in urban India continue to have a much higher chance of surviving the first year than those born in rural India. The latest data on infant mortality rate (IMR) for 2019 released by the census office indicates the poor quality of maternal and child health services in rural areas as well as limited access to these.

The IMR of urban India is 20 (20 babies below one year dying out of every 1,000 babies born) compared to 34 in rural areas, showing a stagnation in the efforts to bridge the rural-urban divide. If anything, the gap has widened marginally in the five years to 2019.

While all states have narrowed the gap in IMR between rural and urban areas, the difference continues to be alarmingly high in Assam, and MP, where rural areas account for 86% and 72% of the total population respectively Odisha, Rajasthan and Gujarat have shown the most remarkable improvement in bridging the gap in IMR between rural and urban areas.

Rural Odisha had the second highest IMR of 68 in the country in 2009 while its urban IMR was 46. It steadily brought down the gap to a single digit and by 2019, the rural and urban IMR were 39 and 30 respectively. Similarly, Gujarat too has significantly reduced the gap in survival of infants between urban and rural areas in the last decade. In 2009, the rural and urban IMRs were 55 and 33 respectively, which narrowed to 29 and 18 by 2019.

The gap between rural and urban IMR (65 and 35) was the highest in Rajasthan in 2009, and its rural IMR was among the highest in India. It has not only brought down rural IMR, it has also narrowed the gap between rural and urban areas (38 and 25) by 2019, a significant improvement from where it had started.

Rural MP continued to have the highest IMR in the country in 2009 (72), 2014 (57) and 2019 (50). Though an IMR of 57 in 2014 was a huge improvement over 72 in 2009, by 2019 the pace of improvement had slowed down as rural IMR came down to just 50 in 2019. Moreover, the ruralurban gap remained the second highest after Assam, which also showed little progress in bridging the gap.

Several states have reduced the rural-urban gap in infant survival to single digits. The gap remains in double digits and almost unchanged between 2014 and 2019 in UP, where 78% of the population lives in rural areas.

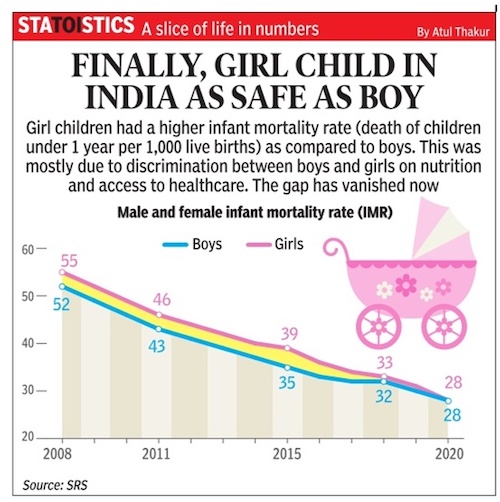

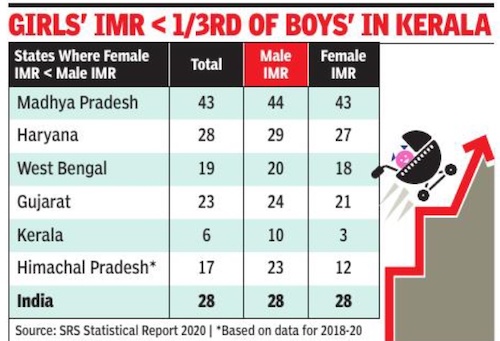

Male and female infant mortality rate

2008-2020

From: August 23, 2024: The Times of India

See graphic:

'Male and female infant mortality rate in India, 2008-2020

Status, year-wise

1961- 2012, Infant Mortality Rates for States & UTs – Male, Female & Total (1961, 2006, 2008, 2011 and 2012)

From: December 22, 2014: The Planning Commission

See graphic:

Infant Mortality Rates for States & UTs – Male, Female & Total (1961, 2006, 2008, 2011 and 2012)

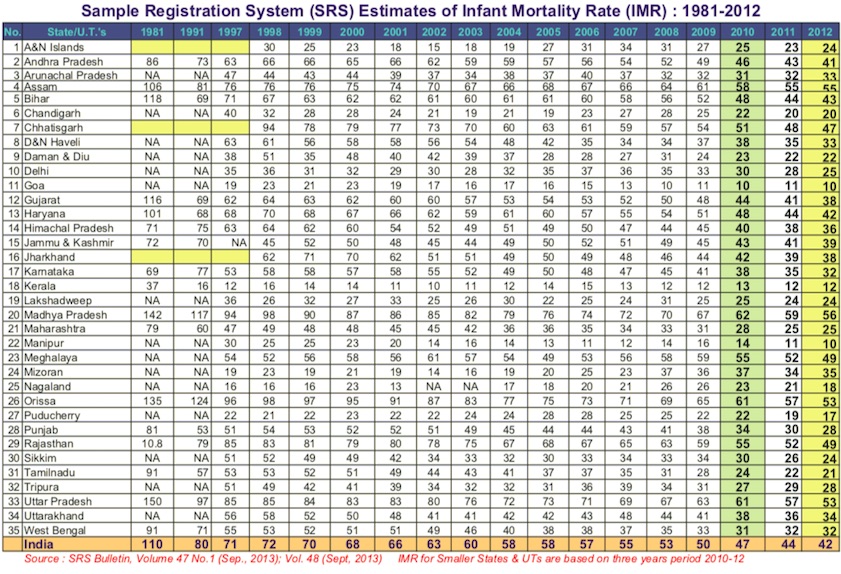

1981-2012: Sample Registration System (SRS) Estimates of Infant Mortality Rate (IMR)

From: December 22, 2014: The Planning Commission

See graphic:

Sample Registration System (SRS) Estimates of Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) : 1981-2012

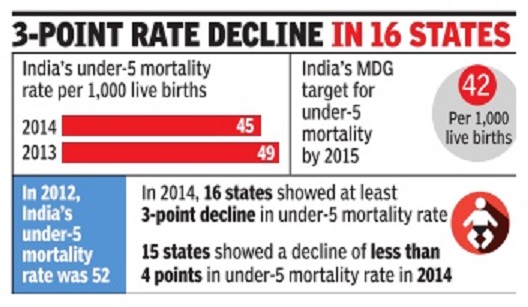

1990-2010, 5% annual decline

Fewer children dying in India

Nearly 5% Annual Decline In Under-5 Mortality, Finds Study

Kounteya Sinha

New Delhi: Nearly 20 fewer children per 1,000 live births are dying in India now, before reaching 28 days of life, than they did two decades ago. As far as post-neonatal deaths are concerned, India is now losing 15 fewer lives per 1,000 live births than it did in 1990. Among children aged 1-4 years, nearly 30 fewer children are dying now than 20 years back.

According to a new study published in medical journal ‘Lancet’ child deaths worldwide are falling faster than earlier thought. Scientists predicted that about 7.7 million children under 5 would die in 2010, down from nearly 12 million in 1990. The deaths this year would include 3.1 million neonatals, 2.3 million post-neonatals and 2.3 million deaths of children aged between 1 and 4.

According to new research by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington, under-5 mortality has reduced by 35% since 1990. The global decline during the past 20 years is 2.1% per year for overall under-5 mortality and for neonatal mortality, 2.3% for post-neonatal mortality and 2.2% for mortality in children aged between 1 and 4.

India is recording a nearly 4-5% annual decline in under-5 mortality. “We’re quite a bit further ahead than we thought,” said Christopher Murray, one of the paper’s authors and director of IHME.

Murray and colleagues assessed information from 187 countries from 1970 to 2009. They found that child deaths dropped by about 2% every year, lower than the 4.4% needed to reach the UN’s target of reducing child deaths by two-thirds by 2015.

The study said 31 developing countries were on track to meet the Millennium Development Goal by reducing child deaths by 66% between 1990 and 2015.In 1990, 12 countries had an under-5 mortality rate of more than 200 deaths per 1,000 live births. Today, no country has an under-5 mortality rate that high, according to IHME estimates.

Compared to India, Pakistan too hasn’t done a bad job. Against a neonatal rate of 54.8 per 1,000 births in 1990, it now stands at 42.7.

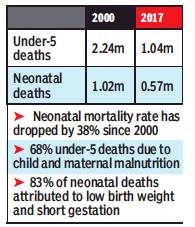

2000>2017: Under-5 mortality rate halved

Under-5 mortality rate halved from 2000 to ’17, May 13, 2020: The Times of India

From: Under-5 mortality rate halved from 2000 to ’17, May 13, 2020: The Times of India

Two scientific papers on child survival published by the India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative depicted a significant decline — 49% — in the under-5 mortality rate (U5MR) between 2000 and 2017, but it pointed out inequality between states and wide variations between districts.

While there is a variation of 5-6 fold in the rates between states, there is also a variation of 8-11 fold between districts, noted the report published in the Lancet. The initiative is driven by the Indian Council of Medical Research and the Public Health Foundation of India, among others. The findings show there were 1.04 million under-5 deaths in 2017, down from 2.24 million deaths in 2000.

Most under-5 deaths in UP, Bihar comes second

Neonatal deaths in India have gone down from 1.02 million deaths in 2000 to 0.57 million deaths in 2017. Neonatal mortality rate (NMR) has dropped by 38% in India since 2000. Sixty-eight per cent of under-5 deaths in India are attributed to child and maternal malnutrition, whereas 83% of the neonatal deaths to low birth weight and short gestation. The highest number of under-5 deaths in 2017 were in UP (312,800, which included 165,800 neonatal deaths) and Bihar (141,500, including 75,300 neonatal deaths).

U5MR and NMR were lower with the increasing level of development of the states. In 2017, there was a 5.7-fold variation in U5MR ranging from 10 per 1,000 live births in the more developed state of Kerala to 60 in lessdeveloped UP, and a 4.5-fold variation for NMR ranging from 7 per 1,000 live births in Kerala to 32 in UP.

“The research paper has shown that India has made positive strides in protecting the lives of newborns over the last two decades,” Niti Aayog member V K Paul said.

2004-11, best/worst Infant Mortality Rate, state-wise

See graphic: Indian states with the best/ worst infant mortality rate, 2004-12

2005-22

July 12, 2023: The Times of India

New Delhi: People in India who are multi-dimensionally poor and deprived under the nutrition indicator declined from 44% in 2005-06 to 12% in 2019/21 and child mortality declined from 4% to 1. 5%, according to the latest Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI). Those who are poor and deprived of cooking fuel declined from 53% to 14% and those deprived of sanitation was declined from 50% to 11. 3%. In the drinking water, those deprived fell from 16% to 3%; lack of access to electricity came down from 29%to 2% and housing from 44% to 14%.

“India saw a remarkable reduction in poverty. Large numbers of people were lifted out of poverty in China (201014, 69 million) and Indonesia (2012-17, 8 million),” the UNDP said in a statement.

The report noted that deprivation in all indicators declined in India, and the poorest states and groups, including children and people in disadvantaged caste groups, had the fastest absolute progress.

The latest update of the global MPI with estimates for 110 countries was released on Tuesday by the United Nations Development Programme and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) at University of Oxford.

According to the report 1. 1 billion out of 6. 1 billion people (just over 18%) live in acute multi-dimensional poverty across 110 countries. Sub-Saharan Africa (534 million) and South Asia (389 million) are home to approximately five out of every six poor people. Children under 18 years old account for half of MPI-poor people (566 million).

2011, Delhi and the other metros

Goal missed, city infant mortality capital

Even Large States Like TN And Maharashtra Score Higher

INSIGHT GROUP The Times of India 2013/09/01

New Delhi: The bad news is that Delhi has the highest infant mortality rate (IMR) among all the metros and at the current sluggish pace at which the figure is being reduced the capital would achieve its goal of reaching an IMR of 15 only in 2030. The good news is that the utilization of public health facilities is over 60%, much higher than in most states.

From an IMR—a measure of how many die within the first year for every 1,000 live births—of 33 in 2004-09, Delhi has progressed at a crawl to touch the current IMR of 28. The Delhi Human Development Report (DHDR) 2013 pointed out that much larger states like Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu had achieved IMRs of 25 and 22 respectively despite having substantial rural populations, higher levels of poverty and a less intensive network of public health infrastructure. In the Delhi Development Goals set in 2006, the target was to achieve an IMR of 15 by 2015.

Segregating infant deaths shows that most happen in the early neonatal period (up to seven days after birth). The decline in postneonatal (28 days to one year) deaths, has been cut by 62%, compared to declines in neonatal (less than one year) and early neonatal deaths of 35% and 26% respectively. The major reasons for this scenario have been identified as inadequate neonatal care in health facilities and the significant proportion of deliveries still happening at home-—about 20%—which kept women out of the coverage of essential maternal health services. The report argued for urgent efforts to ensure improved coverage of maternal and child health services in Delhi.

Yet, the Perception Survey carried out for the DHDR revealed that across different socio-economic groups a large chunk used the public health system, the proportion varying fro6-21m over 75% in low income groups to 45% in high income groups.

2011-14: highest in the 8 poorest states

8 states report 71% of total infant deaths

Subodh.Varma@timesgroup.com

The Times of India Aug 19 2014

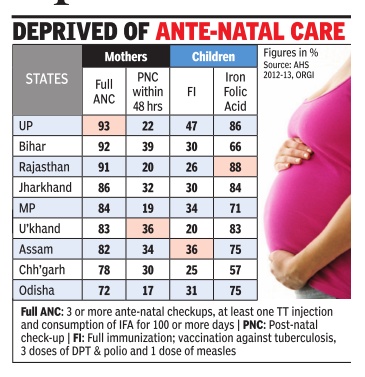

Have you ever wondered why infant mortality rate (IMR) and maternal mortality rate (MMR) are going down so slowly in India?

Part of the answer can be found in a recent survey report put out by the Census office. The eight most-poor states surveyed are home to half the country's population. And, it is in these states that 71% of infant deaths, 72% of deaths of children under-five years, and 62% of maternal deaths take place.

The key reasons for MMR include not getting proper treatment and child-birth related complications. More than three quarters of pregnant women in these states don't undergo full ante-natal checkup (ANC). They are sup posed to get at least one checkup every three months (three in all), one tetanus injection and iron supplement for at least 100 days. In UP, Bihar and Rajasthan over 90% the women don't get full ANC.

A very large proportion of mothers don't get examined within 48 hours of delivery . In Odisha, this proportion is low at 17% but in Bihar it has touched 40% mark. On both these counts, there has been some improvement in all states since 2011 when a baseline survey was done. But, at this rate it will take years to bring it to acceptable levels.

The reason for children's vulnerability to diseases and death is revealed by two key statistics. From one third to nearly half the infants aged 12 to 23 months don't get fully immunized. In UP 47% infants re main unvaccinated, in Assam 36%. This is despite a huge immunization programme conducted by the government.Full immunization includes TB, DPT, polio and measles.

Iron supplementation is a necessity because nearly half the new borns in our country suffer from anemia, as do their mothers. Again, three quarters or more children reported not receiving IFA tablets in the last six months, except Bihar where 66% did not get them.The numbers are staggering: in four states over 80% children were not getting the life giving supplement.

The states covered in the survey are: UP , Bihar, Rajasthan, MP , Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha, Uttarakhand and Assam.

2006-2012: the state-wise position

UP, MP, Assam fail to stem infant mortality Himanshi DhawanThe Times of India Dec 01 2014

New Delhi

Disparity In States Performances Despite Funding

A decade after India committed to a national health policy to provide improved access to healthcare, there is growing inequality in infant health across India. Tamil Nadu, Delhi and Maharashtra have improved on their already superior health outcomes while poorer performing states like Uttar Pradesh, Assam and Madhya Pradesh have slid, a study has found.

Lowering of infant mortality rate is a priority of the National Rural Health Mission and part of the UN millennium development goals that India has committed to. In India, IMR has declined from 57 per 1,000 live births in 2006 to 42 per 1,000 live births in 2012.

Think tank Swaniti Initiative's analysis of state-level IMR data from 2006-2012 suggests that despite huge infusion of funds in NRHM, there is growing national disparity in infant health. None of the poorly performing states were able to achieve a rate of decline close to what the best performing states have achieved. The interstate inequity grew between 2006 and 2012, despite NRHM providing additional funding to such states. Out of the seven states with the lowest IMR in 2006, four achieved a de crease of 29% or more.

According to Swaniti “Infant mortality is impacted by access to nutritional food and sanitation. Improving healthcare is insufficient to address the structural causes of high infant mortality .“

2007, 2012, 2017: improvement, but behind Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal

Rema Nagarajan, June 1, 2019: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, June 1, 2019: The Times of India

India’s infant mortality rate dips, but worries remain

It Still Fares Worse Than Lanka, Bangladesh & Nepal

India’s infant mortality rate (IMR) has fallen from 42 in 2012 to 33 in 2017. However, the pace of change appears to have slowed down when compared to the five years before 2012, when it fell from 55 to 42. Given that India’s IMR is even today worse than those of South Asian neighbours Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Nepal, the slowdown is worrying.

IMR or the number of babies below one year dying out of every 1,000 born alive — considered an important marker of a country’s health system — has been falling steadily for most regions of the world. The global average IMR is 29 and that for low and middle income countries, the category that India belongs to, is 34. The IMR for the European region is 8, the same as Sri Lanka. In South Asia, India has also been overtaken by Bhutan, Bangladesh and Nepal with IMRs of 28, 29 and 30 respectively.

Data from the sample registration system (SRS) just released shows that while the rural IMR reduced marginally from the previous year, urban IMR remained the same for India as a whole. In Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Punjab and Uttarakhand, there was in fact a marginal increase in IMR in urban areas from 2016 with the highest increase in urban Gujarat and Karnataka going from 19 to 22 in both states. In the case of urban Gujarat, the IMR for females went up from 19 to 23, higher than the increase for males.

Madhya Pradesh and Assam had the worst IMR of 47 and 44 respectively, while Kerala and Tamil Nadu recorded the lowest IMR of 10 and 16 respectively. If smaller states and UTs are included, the lowest IMR was recorded in Nagaland and Goa — 7 and 9 respectively. Among states with the highest IMR in 2012, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh showed the biggest improvement with IMR falling for both from 53 to 41 between 2012 and 2017. However, among all states, J&K showed the biggest improvement with its IMR dropping from 39 to 23.

With IMR falling to 33, India is in the company of countries like Tajikistan (33), Botswana (34), Rwanda (32) and South Africa (32). China’s IMR is 9.

In the neighbourhood, the only countries doing worse than India were Pakistan and Myanmar which had IMRs of 66 and 43 respectively.

2013> 2018: a decline

Ambika Pandit, June 30, 2020: The Times of India

From: Ambika Pandit, June 30, 2020: The Times of India

The latest data released by the Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India shows that infant mortality rate in the country has come down to 32 in 2018 from 40 in 2013, a decline of eight points over the last five years and an annual average decline of about 1.6 points. Despite the decline, one in every 31 infants at the national level, one in every 28 infants in rural areas and one in every 43 infants in urban areas still die within one year of life.

Madhya Pradesh paints a worrisome picture with the highest IMR at 48 and Kerala has the lowest IMR of 7. The Sample Registration System — Statistical Report 2018 — also shows that the sex ratio at birth (SRB) has gone up by three points to 899 girls per 1,000 boys in 2016-18 (three years average) from 896 in 2015-2017.

Chhattisgarh has reported the highest SRB (958), while Uttarakhand has the lowest (840). At the national level, the SRB is 900 girls per 1,000 boys in rural areas and 897 in the urban areas.

Chhattisgarh records highest sex ratio at birth in rural areas

In rural areas, the highest and the lowest sex ratio at birth are in the states of Chhattisgarh (976) and Haryana (840), respectively. The SRB in urban areas varies from 968 in Madhya Pradesh to 810 in Uttarakhand. The data on infant mortality rate shows the decline in rural IMR has been to the tune of eight points (44 in 2013 to 36 in 2018) against a decline of four points in urban IMR (27 in 2013 to 23 in 2018). The under five mortality rate (U5MR) has shown a decline of one point over 2018 (36 in 2018 against 37 in 2017). There has been a decline of two points in female U5MR during the period, while the male U5MR has remained the same.

The Sample Registration System is the largest demographic survey in the country mandated to provide annual estimates of fertility as well as mortality indicators at the state and national level. The report contains data the year 2018 for India and bigger States/UTs. The estimates are segregated by residence and also by gender.

The report shows that total fertility rate declined from 5.2 to 4.5 during 1971 to 1981 and from 3.6 to 2.2 during 1991 to 2018. The TFR in rural areas declined from 5.4 to 2.4 from 1971 to 2018.

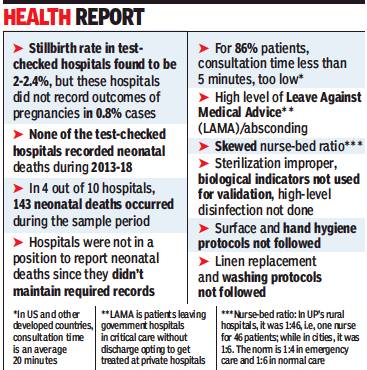

2013-18: UP hospitals under-reported infant deaths

Pradeep Thakur, Nov 23, 2019: The Times of India

From: Pradeep Thakur, Nov 23, 2019: The Times of India

In a presentation made to PM Narendra Modi, the comptroller and auditor general (CAG) said that their recent audit of hospitals in UP reveals infant mortality is under reported — stillbirth data is skewed while neonatal deaths are not recorded by district hospitals at all.

CAG’s findings could raise questions on infant mortality statistics as the auditor further said hospitals surveyed don’t have vital emergency medicines and steroid injections to handle premature deliveries. He said rural areas hospitals have huge shortfall of nurses while there was no protocol followed on hygiene and linen replacements.

A CAG verification of records on total number of deliveries and live births in 10 hospitals revealed that the stillbirths were 2.2% as against the average still- birth rate of 1.63% claimed by UP as per 100 pregnancy outcomes in the state. 0.8% of pregnancy outcomes were not recorded by these hospitals. The audit reportobserved that “in none of the test-checked hospitals, cases of neonatal deaths were recorded” in prescribed Labour Room Register during 2013-18, the period of the sample study.

Source: CAG

2014: Marked improvement in most states

The Times of India, Jun 15 2016

Subodh Varma

Bihar, Gujarat, Rajasthan lag in curbing infant deaths

The steady decline in infant deaths in Indian states appears to be faltering in some while progressing well in others, according to fresh data for 2014 released by the Census office based on an annual sample survey .

Some of the more back ward states like Assam, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh did well in bringing down infant deaths, but Gujarat, MP, Odisha, Rajasthan and Uttarakhand showed an alarming slowdown. Infant mortality is a key measure of people's health and the health delivery system's efficacy . Most such deaths occur in the absence of well-equipped delivery rooms and doctors or when mother and child are weak. Oddly, for the first time, information for all the states has not been released in the annual Sample Registration System (SRS) Bulletin. Out of the 36 states and union territories, information for only 23 has been put out.

Left out are all southern states and some others like Maharashtra and West Bengal. Rohit Bharadwaj, Deputy Registrar General, told TOI that data for all states is yet to come in, ascribing the delay to preoccupation with a baseline survey released recently .

This latest SRS Bulletin for 2014 was due in December 2015 but has been released six months late.

Parsing the rural-urban and male-female data confirms that there is something going wrong in many states. For instance, Rajasthan and Bihar show an increase in infant mortality in rural areas, while Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh show no change over the previous year.

Gujarat, Jharkhand and Rajasthan show a worrying increase in female infant mortality in rural areas.

In urban areas, Bihar and Gujarat show increase in infant death rates, while female infant deaths increased in UP. This reflects the growing share of population which cannot afford access to otherwise plenti ful healthcare facilities in India's cities and towns.

Among the smaller states, infant mortality has increased in Manipur. In Meghalaya, female infant mortality has increased.Nagaland, Sikkim and Tripura show healthy declines in infant death rates.

The predominantly urban union territory of Chandigarh has shown an increase in infant deaths, driven by a rise in female infant mortality. Delhi, also largely urban, has shown a decline.

An all-India picture will emerge only after the system data for other states is released, which Bharadwaj assured would happen in the coming weeks.

2015-16: Decline in Infant Mortality Rate

The Times of India, January 21, 2016

Sharp decline in maternal, child mortality rate

The overall health status of Indians has improved substantially with a sharp decline in key indica ors like maternal and child mortality , fertility rate and malnutrition over the past decade, according to the fourth national family health survey (NFHS-4) 2015-16, which called upon the government o focus more on equity .

As per the findings of the survey , the immunisation coverage has also increased significantly across the country .

Results for the first phase of the fourth survey , covering 13 states and two union erritories, showed these states recorded an infant mortality rate (IMR) of less than 51 deaths per 1,000 live births, with Andaman recording the lowest of 10 deaths and Madhya Pradesh recording 51.

The current national MR is 37. Most states fared dramatically well as compared to the results of the previous survey (2005-06). However, despite the remarkable improvement, some states like Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Meghalaya continue to project a grim picture, though the status in these states has shown marginal improvement as compared to the previous survey .

For instance, though nutrition rates among children have improved in almost all the 13 states and two union territories, stunting continues to be a major concern in Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Meghalaya where over 40% children are stunted.

Anaemia also continues to be a major concern impacting the health of both women and children. In Meghalaya, the number of anaemic women in productive age has increased from from 46.2% during NFHS-3 to 56.2% in NFHS-4. In Haryana, the percentage of anaemic women has gone up from 56.1% to 62.7%, whereas in Goa, it has gone up from 38.2% to 48.3%.Madhya Pradesh has witnesses a marginal decline from 74% to 68.9%.

Data showed institutional deliveries witnessed a marked improvement with more than nine in ten recent births taking place in health care facilities in Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Andhra Pradesh, Goa, Karnataka, Puducherry , Sikkim, Tamil Nadu, and Telangana. In Bihar, institutional deliveries rose from 19.9% in 2005-06 to 63.8 % in 2014-15.

Similarly , institutional deliveries rose from 35.7% to 80.5% in Haryana and 26.2% to 80.8% in Madhya Pradesh.

Though immunisation coverage varied widely among states, at least six out of 10 children received full immunization in 12 of the 15 states and union territories.

2016: the best and worst states

See graphic.

Low and High Mortality rates, state-wise in India and a comparison with the world

2018: The state-wise picture

July 2, 2020: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, 1 in 5 deaths in MP is a child under 5, just 2% in Kerala, July 2, 2020: The Times of India

Deaths in the 0-4 year age group account for a shocking 20% of total deaths or one in every five in Madhya Pradesh. In contrast, deaths in this age group account for just 2% or one in 50 of total deaths in Kerala, reports Rema Nagarajan.

This was revealed in the Sample Registration System 2018 report released recently by the Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India.

A high proportion of deaths in the 0-4 age group is not unique to Madhya Pradesh and is the case among states with poor development indices.

These include Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Bihar in that order with about one in six deaths is in the 0-4 age group.

Child death rate low in TN, Punjab, HP & Maha

Kerala Has The Lowest Rate Of 10

Such a high proportion of deaths in the 0-4 age group is clearly because of the high under-five mortality rate (the probability of dying before 5 years of age for every 1,000 newborns) in these states. Madhya Pradesh has the highest under-five mortality rate of 56 and Kerala has the lowest of 10.

Other than Kerala, the proportion of deaths in the 0-4 age group is low in Tamil Nadu, Punjab, Himachal Pradesh and Maharashtra in that order. Again, these states also have relatively low under-five mortality rates. In India as a whole and in most states, the deaths in the 0-4 age group constitute a higher proportion of total deaths in rural than in urban areas, except in a few states such as Uttarakhand and Punjab, where the proportion is higher in urban areas.

In some states, the difference in the proportion of deaths in the 0-4 age group between rural and urban areas is huge. The biggest gap is in Assam, where 0-4 age group deaths are 6% of total deaths in urban areas and 16.5% in rural Assam. Similarly, in MP, the proportion is just 13.4% in urban areas and 22% in rural areas. This gap could be an indication of poor health facilities in rural areas compared to the urban centres of a state. Gujarat and Rajasthan are two other states where the gap in proportion between rural and urban areas is greater than the gap at the all-India level.

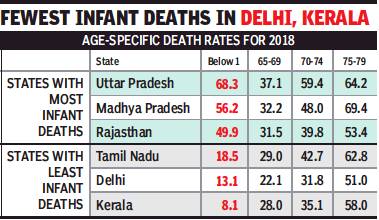

The best and worst states

From: Rema Nagarajan, In UP & rural Guj, it’s harder for a baby to survive than a 75-year-old, July 6, 2020: The Times of India

Who is more likely to die — an infant less than one year old or someone in their late seventies? This may seem like a no-brainer, but in Uttar Pradesh or rural Gujarat, the infant is more likely to die than a 75-79-year-old person.

This shocking reality emerges from data in the recently released SRS 2018 report. The data also shows that in most of India’s big states, the death rate among those less than a year old is higher than those aged 65-69. This is correlated to high infant mortality rate (IMR), which India has been struggling to bring down. Thus, in Kerala and nine other states, the death rate of infants is lower than for any age group above 65 years. Most of these states are also those with the lowest IMR.

The death rate for infants aged less than a year in UP is 68.3, higher than the 64.2 for the 75-79 age group.

In rural Gujarat, the death rate for infants at 52 was significantly higher than 45.9 for the 75-79 age group.

Infant death rate low in Kerala, Delhi and 3 other states

Age-specific crude death rate in a year is the total number of deaths in a particular age group in that year for every thousand of the population in that age group. IMR is the ratio of the number of deaths of children under one year to the total number of live births in that year. While the values of crude death rate of children under one year and IMR are close, they do not correspond exactly.

Kerala, Delhi, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab and West Bengal, in that order, have the lowest IMR and have lowest crude death rate of infants under one year. But J&K, which has a low IMR of 22, is among the states where crude death rate of those under one year (29.4) is more than death rate in 65-69 age group (22.3). MP has highest IMR of 48, but is below UP when it comes to crude death rate in the below-oneyear age group though UP’s IMR is lower at 42.

“High IMR is due to a mix of medical and socioeconomic reasons. So many states continue to have a relatively high IMR even after their health services improve because the socioeconomic reasons continue to contribute to the death of infants. But a lot of preventable mortality in this age group is definitely due to inadequate health services,” explained Dr N Devadasan, former director of the Institute of Public Health. There is an obvious gender skew too, with two factors contributing to it — higher IMR among girls than boys and lower death rates among older women than men. As a result, there are states besides UP and Gujarat where an infant girl is more likely to die than a 75-79-year-old woman, particularly in rural areas. For instance, in rural Madhya Pradesh, girls in the below-one-year age group have a crude death rate of 57.6 compared to 29.7 and 44.8 for women in the 65-69 or 70-74-year age groups. In many states, first year of life is more dangerous than its twilight.

2009, 2014, 2019

Rema Nagarajan, Oct 26, 2021: The Times of India

From: Oct 26, 2021: The Times of India

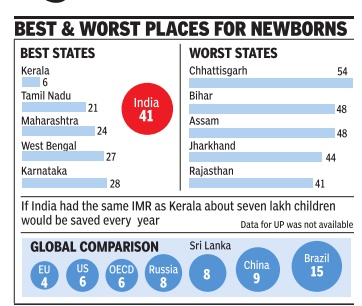

India’s infant mortality rate has dropped to 30, but the decline has slowed down in the last five years in most states, just released data from the sample registration system (SRS) shows. It also reveals the enormous differences between states with Kerala having an IMR equal to the US and Madhya Pradesh faring worse than even Yemen or Sudan. Worryingly, it is the worst-off states in which the slowdown in improvement is most marked, Bihar being an exception.

India’s IMR — defined as the number of babies less than a year old who die for every thousand live births — improved in the decade between 2009 and 2019 from 50 to 30, but is still worse than Bangladesh’s and Nepal’s, both at 26, though better than Pakistan’s (56).

All states have shown improvement in IMR from the year before. However, after showing remarkable improvement of 11 points from 50 to 39 from 2009 till 2014, it has slowed down in the last five years. Among larger states showing accelerating improvement are Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir and West Bengal. In the case of Kerala, after stagnating at an IMR of 12 from 2011 till 2015, it improved to 6 in the last five years, a level that matches that of the US.

States that saw the greatest slowing down in improvement of their IMR are Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. From double digit improvement between 2009 to 2014, the pace of improvement in these states slowed down to single digit. The improvement in IMR does tend to slow down as it gets lower, but most of these states are at a level where this would not apply.

After Kerala, Delhi has the lowest IMR of 11 followed by Tamil Nadu (15) among the larger states. Globally, the lowest IMR of 2 has been recorded in Finland, Norway, Iceland, Singapore and Japan. India’s IMR for 2019 is about a quarter of what it was in 1971 (129). IMR is widely accepted as a crude indicator of the overall health scenario of a country.

2019, 2021

Rema Nagarajan, April 6, 2022: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, April 6, 2022: The Times of India

Almost one in five deaths in Madhya Pradesh and over a sixth in Uttar Pradesh are of children aged 0-4. In contrast, this age group accounts for just one in sixty deaths in Kerala. The national average is about one in nine. The huge difference is accounted for by two factors. One, states like Madhya Pradesh (9. 1%) or UP (8. 2%) have a larger proportion of their population in the 0-4 age bracket than Kerala (6. 5% or Tamil Nadu (6%). Also, MP or UP have much higher death rates for the 0-4 age group than Kerala or Tamil Nadu — 13. 7 and 14. 3 versus 1. 8 and 3. 8.

The combined effect of a younger population and higher death rates in the really young means they account for a larger proportion of deaths. As a result, the SRS (Sample Registration System) Statistical Report of 2019 released recently showed that a larger proportion of children below four years were dying than elderly in 60-69, 70-79 or 80 and above age groups in Madhya Pradesh. It was similar in Uttar Pradesh, though marginally better.

In MP, for instance, the 0-4 age group constituted 18. 9% of all deaths, a higher proportion than either those in their sixties (17. 8%), seventies (17. 8%) or eighty plus (15. 1%). Almost the same is true for UP, with 0-4 accounting for 18%, those in their sixties for 18. 2%, the seventies for 18. 8% and the eighty plus for 15. 4%.

In almost every state the chances of survival of children who survive the first year of life improves vastly as infant mortality or the death of children below one year accounted for over 80% of deaths in the 0-4 age group. In some states like Jammu and Kashmir, Assam and Chhattisgarh, infant deaths are 90% or more of deaths in this age group. Infant deaths were just 75% of child deaths only in Kerala, where deaths of babies below one year was brought down to just 1. 2 per thousand population.

The greatest improvement since 2011 was in Bihar where infant deaths came down from being a quarter of the deaths across all age groups to 17% by 2019. In comparison, Madhya Pradesh brought down the share of 0-4 deaths from 24. 4% to 19% and Uttar Pradesh from 25% to 18%. Like Bihar, Assam also showed significant improvement bringing down the share of 0-4 deaths from 22% to 14% over the same period.

Among states with already comparatively low child mortality, Jammu and Kashmir showed the greatest improvement with child deaths as a proportion of total deaths coming down from 14. 4% in 2011 to just 6. 9% in 2019 followed by Delhi, where it came down from 13% to just 5. 8%.

2020

Rema Nagarajan, Oct 4, 2022: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, Oct 4, 2022: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, Oct 4, 2022: The Times of India

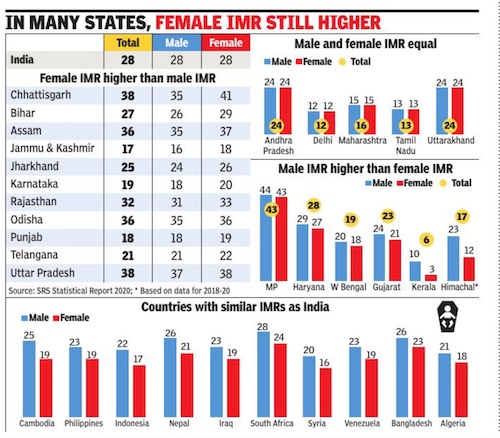

India, which had the ignominious reputation of being the only country in the world where a larger proportion of girls below the age of one died than boys, finally saw its male and female infant mortality rate (IMR) equalise in 2020, at 28. In 16 states, IMR remained higher for female babies, but the gap had reduced since 2011.

Infant mortality rate is the number of infant deaths for every 1,000 live births.

In rural India, though the gap had reduced, female IMR remained marginally higher than male IMR. However, in urban India, where the gap between male and female IMR was higher in 2011, the female IMR fell below that of males by 2020.

In 2011, all states had higher IMR for female babies than male, except Uttarakhand, where the two rates were equal. But the SRS Statistical Report 2020 showed that in five states and the national capital territory, IMR was the same for babygirls and boys and in eight states, IMR for females was lower.

Chhattisgarh had the highest gap in 2020, with a male IMR of 35 compared to female IMR of 41. Though its overall IMR fell from 48 to 38, it is one of the few stated where the gap increased in 2020 over 2011.

Almost same male, female IMR only in India

Other states which saw a marginal increase in the gap included Bihar, Assam and Karnataka. In all states, the rural IMR was higher than in urban areas. But the gap between male and female IMR was greater in urban areas in many statesincluding Himachal Pradesh, Gujarat, Punjab, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Maharashtra and Haryana in 2011. By 2020, this trend was reversed in most of these states. UN data for 2020 shows that among countries where the IMR was above 20, India was the only one where male and female IMR were almost the same. In every other case, male IMR was higher than female IMR by at least 2 years. The only other countries where the gap between male and female IMRs was one or less were those where infant mortality has been reduced to single-digit levels.

2023

From: Sep 20, 2025: The Times of India

See graphic:

Indian states with the highest and lowest infant mortality, 2023

Status, region-wise

Delhi

2005-15: Delhi—neo-natal deaths double

The Times of India, Aug 04 2016

Neonatal deaths double in a decade, infants also at risk Advances in medical technology and health infrastructure in the city seem to have done little to save children from dying. The latest birth and death registration data shows that the number of neonatal deaths -children dying within 29 days -has nearly doubled in the last 10 years from 3,183 in 2005 to 5,908 in 2015.

The number of infant deaths (children who die before turning a year old) in the capital has also gone up from 4,182 to 8,695 over the last decade. This data was released in the annual report prepared by the directorate of economics and statistics of Delhi government on registration of births and deaths in 2015.

The data shows infant deaths were caused by hypoxia, birth asphyxia and other respiratory conditions (20.34%) followed by septicaemia (11.36%). Slow fetal growth, fetal mal nutrition and immaturity was the third-most common cause of infant deaths (7.26%).

“Infant deaths are 6.98% of the total registered deaths in Delhi, which is slightly higher than 6.67% recorded during the preceding year. Of these infant deaths, 8,612 were institutional and 83 non-institutional. The infant mortality rate per thousand live births in 2015 is 23.25%, which are higher in comparison to preceding year,“ said officials.

Public health officials have are shocked at the neonatal and infant mortality rate. “The government is celebrating the increase in institutional births, but there is no focus on improving infrastructure and managing shortage of staff in hospitals.Often, patients are referred to bigger hospitals at the last minute due to lack of equipment or expertise at the smaller centres,“ said a doctor.

Maternity centres and some government-run health institutions, experts said, lack facilities for caesarean-section delivery . “There are cases of women delivering in ambulances every day . This is because there is no trust in local maternity centres and patients travel long distance at the last minute for delivery ,“ said a public health expert. He also blamed poor nutrition of mothers for the high infant mortality rate.

Doctors said that public sector hospitals are overburdened and the private sector is unaffordable for most people. “The cost of ICU care for a newborn in most big hospitals is Rs 10,000-30,000. The government should add newborn care facilities in peripheral hospitals,“ a senior doctor said.

Social activists working for the rights of women and the girl child point towards the need for focussed measures to build awareness against sex determination tests and crackdown on ultrasound clinics offering such facilities illegally .

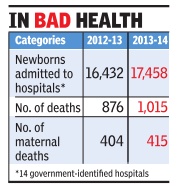

2013-14: IMR highest ever, Delhi

More infants died within month of birth last year

December 17, 2014

The number of children dying in Delhi within 29 days of their birth has gone up in the past one year -from 876 in 2012-13 to 1,015 in 2013-14.Latest statistics released by Delhi government show maternal mortality , an indicator of public health system, has witnessed a sharp increase during the same period. According to government data, total 2,30,961 deliveries (1,96,109 at public hospitals and 34,852 at private hospitals) were conducted in 2013-14. Data on neonatal deaths only includes 17,458 newborns admitted to the Sick Neonatal Care Unit (SNCU) at 14 government hospitals.

Experts say many neonatal deaths are still not reported. “The increase in number of such deaths should be seen in correlation with the total number of births. Also, we still have hundreds of newborn deaths being categorized under the still birth category,“ said T Sunderaraman, a public health expert. He added that poor infrastructure and human resources at SNCUs is also to blame.

“Neonatal ICU is a highly specialized service. It requires state-of-the-art infrastructure, which is completely missing from facilities run by Delhi government and municipal corporations,“ said Sunderaraman.

Experts say premature births contribute the highest to neonatal deaths. Infection is the second leading cause, followed by asphyxia (shortness of breath) and diarrhoea.

Data also shows an increase in the number of children between 1-3 years being detected with protein energy malnutrition and low weight.

There is bad news for the government on family planning front too. Except for Insertion of Intrauterine Contraceptive Device (IUCD), the usage of all other contraceptive methods has witnessed a significant decline in the last one year. This includes condoms, oral pills and sterilization of both men and women.

2014-15: IMR on a rise in Delhi

The Times of India, Jul 09 2015

Durgesh Nandan Jha

One in every 45 kids born here dies before first b'day

Infant mortality rate (IMR) is one of the key health indicators of a state, but Delhi, despite being the hub of high-end medical services in India, continues to fare poorly on it compared with larger states like Kerala.

The Economic Survey Report 2014-15 shows that 22 out of every 1,000 children born in Delhi in 2013 (the latest available data) died within a year of birth.That's one in 45 children. In Kerala, the IMR was less than 12 per 1,000 births, or one in 83.

The number of children dying within 29 days of birth in Delhi--called neonatal mortality rate (NMR) --was 15 per 1,000 births in 2013. Experts said conditions arising in the period immediately before and after birth cause the maximum infant deaths, followed by hypoxia, birth asphyxia and other respiratory conditions.

“The government is promoting institutional childbirth but the infrastructure required for these remains poor. Many women go to private nursing homes for de livery where there is no facility for giving emergency care to the newborn if a situation arises,“ said Dr Ajay Gambhir, president of National Neonatology Forum.He said the number of nurses is also not adequate.

In the year 2001, Delhi's IMR was 24 per 1,000 births.It reduced to 13 per 1,000 in 2004 and 2005 but has been on the rise ever since. Delhi's NMR was 14 per 1,000 in 2001 and reduced to 9 per 1,000 in 2004 before increasing again.

Dr Sidharth Ramji, who heads the neonatology unit at Lok Nayak Hospital, said public sector hospitals are overburdened and the private sector is unaffordable for most people. “The cost of ICU care for a newborn in most big hospitals is Rs 10,000-30,000 which the poor and lower-middle classes cannot afford. The government should add newborn care facilities in peripheral hospitals to take the burden off bigger hospitals,“ he said.

Dr Ramji added that none of the CATS ambulances run by the state have incubators which are a must to transport critically-ill newborns. Experts also stressed on the need to reduce infection in children's wards and improving the nursing facilities so that attendants are not allowed in the emergency areas.

Kerala

2015-16: Kerala at OECD level

Indian Rate 7 Times Worse Than Best State

Kerala's infant mortality rate (IMR) -the num ber of children under the age of 1 who die for every 1,000 born -has been brought down to 6, a level equal to that of the US and the average for developed nations, according to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) of 2015-16. To put it in perspective, if India, with a current IMR of 41 could get it down to 6, around seven lakh children would be saved each year.

Kerala had been strugg ling over the past decade to bring down the IMR to a single digit from 12 where it has been stuck since 2009, according to the Sample Registration Survey (SRS) conducted by the office of the registrar of census. In the last NFHS done in 2005-06, Kerala's IMR was 15. An IMR of 6 is lower than that of countries like Russia (8), China (9), Sri Lanka (8) and Brazil (15).

Kerala continues to be way ahead of other Indian states on this measure, the closest big state to it being Ta mil Nadu with an IMR of 21.

Paediatricians and public health experts in Kerala, however, are more sceptical than overjoyed at the new numbers. While many are willing to believe that the IMR has dipped below 10 in recent years, a dramatic fall to six is something they are skeptical about. With the falling number of births, they wonder if the number of infants in the overall NFHS sample for Kerala was adequate to measure IMR accurately.

Over 60% of infant mortality is neonatal mortality (death within the first 28 days of birth). Most of these deaths are due to prematurity, low birth weight and asphyxia at birth.“There has been a focus on IMR as part of the millennium development goals, which gained momentum in the last seven to eight years even though the goals were launched in 2000. In our own hospital, we have seen neonatal mortality fall by half,“ says Dr Mohandas Nair, additional professor in paediatrics in Kozhikode Medical College. Several Sick Newborn Care Units and New Born Stabilisation Units have been set up in public hospitals in the state with central government funds. The Navjaat Sishu Suraksha Karyakram of the central government has helped train nurses in all government hospitals and even private hospitals in basic newborn care and resuscitation.

Dr Nair feels these efforts could have led to a steady decline to a single digit, most probably around 8 or 9 rather than a sudden fall from 12 to 6.

Dr V Ramankutty, a paediatrician and public health professor of Achutha Menon Centre, in Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology, says it would have been better if the NFHS had indicated a range for the value that accounts for any sample size error. “I am not saying that the IMR of 6 is impossible or wrong. If the range of IMR is 5-7 or 4-8, that would be very good, but if it is 2-12, that's nothing to be happy about. To bring down IMR from such a low level of 12, high technology capital intensive interventions are needed. I don't think that kind of investment in newborn care has happened in Kerala,“ explained Dr Ramankutty .

Better than the USA, 2025: The success story

Rema Nagarajan, Sep 14, 2025: The Times of India

The latest Sample Registration System (SRS) report has highlighted a striking milestone for Kerala — the state had achieved an infant mortality rate (IMR) of 5, a figure lower than even the US (5.6). This achievement is all the more remarkable because for over two decades, between 1995 and 2015, Kerala’s IMR stubbornly refused to fall below 12-15. Breaking free of that stagnation took persistence, innovation, and a rare partnership between the state govt and the paediatrician community.

Infant mortality rate refers to the number of infant deaths under one year of age per 1,000 live births. Even at an IMR of 12, Kerala was well ahead of the rest of the country. However, while India’s IMR fell from roughly 75 to 37 in the same two decades, showing remarkable progress, Kerala’s IMR barely budged. This made the state govt take a hard look at what was holding Kerala back.

The contrast became sharper because maternal mortality had steadily declined. Kerala’s maternal mortality ratio (MMR) fell from 150 in the mid1990s to 61 in 2011-13. In the latest report, its MMR is 30. Rajeev Sadanandan, who was then with the department of health and family welfare in Kerala, credits this success to a confidential review of maternal deaths started by Kerala Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (KFOG) in 2002. “They used to publish a fabulous report every three years called ‘Why Our Mothers Die’. Every maternal death review was seen as a learning exercise and not a fault-finding exercise. This provided a very clear evidence-based template to reduce maternal deaths,” explains Sadanandan.

LIKE MOTHER, LIKE CHILD

When Sadanandan returned to the health department in 2011, he urged the Kerala branch of the Indian Academy of Paediatrics (IAP) to adopt a similar approach for infant mortality. According to the then president of IAP’s Kerala branch, Dr Sachidananda Kamath, the association decided to take up the challenge of bringing down Kerala’s IMR to single digits. “With the help of the National Rural Health Mission and Kerala govt, IAP reviewed infant deaths in four districts,” says Dr Kamath. “We found that prematurity and congenital anomalies together accounted for more than 60% of infant deaths. We suggested interventions such as increasing the level of care and tackling deaths from heart diseases. Boosting neonatal care improved the survival of 28-week-old babies and even newborns weighing 900 gm were able to live.” However, congenital anomalies, which accounted for almost 30% of infant deaths, were more challenging to tackle as they required access to highly skilled surgeons, medical infrastructure and financial resources. “We decided to focus on congenital heart diseases, which is a significant proportion of congenital anomalies in infants,” says Sadanandan, who served as the health secretary for 11 years.

With leadership provided by paediatric cardiologist Dr Raman Krishna Kumar and foetal cardiologist Dr Balu Vaidyanathan in Amritha Hospital, Kochi, the govt launched Hridyam, the first ever population-level programme to address congenital heart diseases in a low-middle-income country. Its web-based application launched in 2017 serves as a registry where any physician in Kerala could add the name of a suspected case of congenital heart disease. Once listed, a paediatric cardiologist would review the online record within 24 hours and classify the case according to urgency. In case there was insufficient information, the cardiologist could direct the District Early Intervention Center at the local level to get further tests done. Patient registrations have risen steadily since launch.

“A lot of deaths happen even before the child reaches the hospital or gets a diagnosis. Hridyam sought to minimise this attrition by ensuring timely screening and referral. Since this involved screening babies, the collateral benefit of screening was that other conditions such as respiratory conditions got picked up. Pulse oximeter screening within 24-48 hours of birth could identify babies who were sick or who could die. This way, we were able to save a lot of babies,” says Dr Krishna Kumar. For this to work, hundreds of paediatricians, obstetricians and sonographers had to be trained to enhance their diagnostic skills. Private and public paediatric cardiac programmes that could be referral centres were identified and empanelled, even as the public sector capacity in three institutions was expanded.

Neonatal transport networks were also strengthened, but risks during transit remained. This is where foetal echocardiography came in. “Kerala’s newborn registry study showed that many babies died before reaching a centre to get surgery. A mother’s womb is the safest transport for a baby. So, the answer was to do foetal echo diagnosis during the mid-trimester scan, which is mandatory for all pregnancies. If a critical heart defect is suspected, the mother is referred to a person trained in foetal echocardiography. If that confirms a critical defect, the mother can be referred to a high-end centre for delivery so that the baby can be taken for emergency surgery soon after birth. It significantly improves the chances of survival,” explains Dr Vaidyanathan. These measures, combined with Kerala’s robust primary healthcare and female literacy, helped cut IMR to 5.

AUDIT MODEL

Death audits also played a pivotal role. But since neither doctors nor hospitals like to do them, how did the medical community adopt it? Dr VP Paily, one of the founders of KFOG, says confidentiality was key, with neither the identity of the patient nor that of the doctor or hospital revealed to assessors. “We only studied the circumstances of the death, the treatment given and whether it was preventable. There were some doubts initially, but once we gained the trust of the obstetricians, it was fine. This was important because 70% of births in Kerala happen in the private sector,” said Dr Paily. The govt, meanwhile, was happy to get robust data without spending any money. This model is now seen as a cornerstone of Kerala’s health gains.

Still, experts warn of challenges ahead. Former IAP national president Dr Kamath notes that while Kerala is ahead of the US, there are several developed countries that have done better. Italy, Singapore, Japan, Korea, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Slovenia, Estonia and the Czech Republic have the lowest IMR of 2. “Within Kerala, there are pockets where the IMR is much higher than 5. We need special strategies for tribal and vulnerable populations. We need to find out why prematurity is high in Kerala. We must take care of adolescent girls — our future mothers — and focus on their nutrition, exercise and the rise of non-communicable diseases among them. We need a good strategy to bring it down further.” Others caution against over-celebration. “All this about Kerala’s IMR being lower than the US is a bit misleading,” says Sadanandan. “SRS is at best an estimate, unlike the US which has an excellent statistical system. What matters is that we’ve managed to sustain single-digit IMR.”

Jharkhand

Jharkhand: Reduction in neonatal mortality

How Jharkhand’s mothers stopped their babies dying

…and why the authoritative medical journal, Lancet, has praised a unique project

B Sridhar

Chakradharpur (West Singbhum): Kusnopur is a hamlet in the area and it is a transformed place. As are some other villages in this mineral-rich district. Indkata, Dengsorgi and Landupoda are also in the grip of a quiet — and happy — revolution. Fewer newborn babies are dying. How has this happened?

Through an extraordinary training project for local tribal women. Prasanta Tripathy runs the NGO Ekjut, which facilitated the training. He says “there is a 45% reduction in neonatal mortality rate as well as a change in practices related to childrearing. Besides, there is a 57% reduction in postnatal depression.”

It’s been a hard slog — for the NGO and its volunteers, and the tribal women. Aantri Koda, 28, of Balundi village, was one of the early trainees. She recounts how hard it was: “When I joined the NGO for training, my husband asked me to concentrate on household chores rather than become a neta. However, my sister in law persuaded him to let me join, citing her own suffering during pregnancy.”

There was resistance from village elders too. Mother-of-two Kulsum Sundi, 33, recalls the gram pradhan opposing volunteers who wanted to assist her when she was pregnant. “He said that they are polluting the culture of our village by carrying semi-naked pictures of pregnant women.”

Nitima Lamay of Ekjut says lack of awareness caused the initial resistance. “Gradually, the senior members of the village started co-operating.” Tripathy says they stress on “participation, learning and action — the ingredients in the making of an empowered mother and healthy baby.”

The NGO started with 20 women in three villages around Chakradharpur six years ago. By now, it has 20,000 trained women, spread across more than a thousand villages in nine districts of Jharkhand and Orissa.

Sumitra Gagrai, Ekjut group coordinator, says the core of the revolution was the community spirit unleashed, when trained female volunteers fanned out across remote villages “to encourage adolescent girls and married women to find practical solutions for good health during the pre and post pregnancy period.”

It was a success and praised as such by ‘The Lancet’, the authoritative British medical journal.

Madhya Pradesh

Rahul Noronha , Little Tragedies “India Today” 22/8/2016

See graphic

Maharashtra

2023

Malathy Iyer, Mohammed Akhef & Sumitra Debroy , Oct 5, 2023: The Times of India

MUMBAI: Roughly 40 children under the age of one die in Maharashtra every day. About two-thirds of those who die are less than a month old.

Consider Nanded, where 24 deaths occurred in a 24-hour period in Shankarrao Chavan Hospital. Of them, 12 were newborns between one and three days old. Six of the newborns had respiratory distress. "It needs to be assessed if manual ambu bags (manual resuscitators) were available in the hospital or senior staff trained in using them were around, said a doctor.

In the Government Medical College on Ghati Road, in Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar, where 18 deaths occurred in a 24-hour period ending Tuesday, two were pre-term babies just a few days old.

Pre-term births big cause

A state health official said, "We have seen an improvement in the last few years. And most of the causes such as congenital abnormality cannot be controlled. The leading causes of neonatal death are prematurity, low birth weight and respiratory distress.

However, a doctor from a hospital in erstwhile Aurangabad said premature births have increased of late. "The main reason for preterm deliveries is maternal nutrition deficiency, which results from lack of awareness. While macro nutrients are consumed, many pregnant women miss out on micro nutrients such as iron, zinc that are equally important and responsible for a child's growth in the mother's womb," said GMCH's associate prof and neonatal section in-charge Amol Joshi.

Noted health activist and paediatrician Dr Abhay Bang, who has been working to tackle infant mortality in Gadchiroli, said two factors contribute to majority of the deaths: neonatal sepsis and preterm births. Interestingly, his research in 39 villages of Gadchiroli revealed significant improvement in incidence of neonatal sepsis, dropping from 16% to 2%. However, the rate of preterm births is unchanged.

More hospital births, more NICU stay

Dr Bang has a different take on the entire issue. He said the sudden surge in deaths could be linked to one significant factor - the rise in hospital deliveries, primarily driven by initiatives like the Janani Suraksha Yojana.

Even in the most remote areas, more mothers are opting for institutional deliveries, leading to a higher number of infants needing specialized care in paediatric and neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). And despite substantial increase in hospital deliveries, government has failed to proportionally increase the healthcare workforce and infrastructure. "While the percentage of women delivering in hospitals has surged from 40% to 80%, healthcare facilities have remained largely unchanged. This disparity is a likely factor contributing to the sudden upswing in infant mortality rates," according to Dr Bang. Furthermore, the majority of government PICUs and NICUs suffer from overcrowding, inadequate staffing, and hygiene deficiencies. Dr Bang emphasizes that neonates, in particular, are highly vulnerable and account for a significant portion of these unfortunate deaths.

Late referrals

Doctors said late referrals are also a reason for higher deaths. "State hospitals are literally the dumping ground where private sector hospitals send a patient who is critical, said an official from department of medical education that runs medical colleges.

Milind Mhaiskar, additional chief secretary of the public health department said in most cases, late referrals of critical cases are proving to be a key reason. "As patients reach late, doctors have little time to activate the full scale of lifesaving measures," he said. Dr Rajendra Saoji, who heads the pediatric surgery department of GMCH Nagpur, said, "Children from the periphery often arrive at these hospitals in a critical condition, many are referred by local private hospitals in a serious state. As government hospitals, we are committed to providing care to all patients and do our utmost to save them. Unfortunately, neonatal care facilities are limited in the region, compounding the challenges we face.’'

Health economist Dr Ravi Duggal said the main reason for higher deaths among neonates are inadequate number of NICUs and trained staff. "Health has low priority as it's not a political issue, resulting in barely 4% of the budget being allocated to it, he added.

(Inputs from Chaitanya Deshpande, Nagpur)

Manipur

2017/ Manipur has lowest Infant mortality rate

HIGHLIGHTS

According to the health ministry report, Manipur’s IMR stands at nine deaths per 1000 live births

According to official records, the state saw a massive decrease in cases of TB, malaria and leprosy

It is hard to believe that the state, mostly in the news for reports of armed conflicts, has been achieving the country's lowest infant mortality rate (IMR) consecutively for the last three years — standing tall amidst other conventionally well-equipped states. According to the health ministry report, Manipur's IMR stands at nine deaths per 1000 live births. The national IMR, according to the latest available data, is 43 deaths per 1000 births. The figure in neighbouring Assam is 62. The key mantras behind the state's success in this regard, according to officials, are better medical facilities, proper and effective immunization, dedicated doctors and health workers, high health consciousness, a tremendous increase in institutional deliveries and women empowerment.

"We have been bagging awards for having the lowest infant mortality rate for three consecutive years from the central health ministry," Manipur family welfare director K Rajo Singh said. "The society in general and pregnant women and their families in particular are very health conscious. Pregnant women never miss the antenatal health checkup in all trimesters," he said. He also spoke on the role of the Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) in spreading health awareness among local communities. Saying there are 4009 such local women health workers who are trained regularly, Rajo said these women facilitate tests before pregnancy, institutional deliveries and proper childcare. Centrally sponsored schemes like the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSK) and Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakaram (JSSK) and standing laws like the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Technique (PC & PNDT) Act and Rules also share the credit in bringing the IMR down, Rajo said.

State family welfare joint director Th Arunkumar said the PN & PNDT Act and Rules was fully implemented in the state in 2003 with setting up of different implementing bodies like the state supervisory board, state advisory committee and the state appropriate authority. 115 ultrasound machines have so far been registered under this programme in both government and private hospitals, he said. "The other aspect is that indigenous people of the state are genetically strong," said Arunkumar.

According to social activists, women in the state possess a natural instinct of taking care of themselves during pregnancy in terms of food intake and daily chores. According to the state health department's official record, the state saw a massive decrease in cases of TB, malaria and leprosy. There have also been an increase in the number of health units, doctors, nurses, number of beds in both government and private hospitals and the health plan budget in the state.

Uttarakhand

2017/ 38 deaths per thousand births

Shivani Azad, October 8, 2017: The Times of India

According to the findings of the Sample Registration System (SRS), an annual survey conducted by the Union ministry of health, Uttarakhand's infant mortality rate (IMR) now stands at 38 deaths per thousand births, which is an increase of 4 points over last year.

This means that more infants are dying in the state than ever before. What is perhaps most shocking about the findings which were released late last month is that among the nine Empowered Action Group (EAG) states -Bihar, Assam, MP, UP, Uttarakhand, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha and Rajasthan(which have been clubbed together since they have the highest infant mortality rates in the country), Uttarakhand is the lone state which has not shown any improvement.

While Madhya Pradesh has im proved its infant mortalities from 50 to 47 this year, UP has reduced deaths from 46 to 43. Similarly , Assam has brought down infant fatalities from 47 to 44, Odisha from 46 to 44, Rajasthan from 43 to 41and Chhattisgarh from 41 to 39. Bihar and Jharkhand, too, have shown an improvement by bringing down deaths from 42 to 38 and 35 to 31 respectively .

Uttarakhand has seen infant mortalities rise from 34 during the last SRS survey to 38 in 2017.

The state had registered a similar IMR of 38 in 2010 but had been showing improvement in its parameters over the years. Dr DS Rawat, former officiating director general in the health department who is also a paediatrician attributed the rise in IMR to “lack of dedication on the part of doctors in the state.“ “The doctors deployed in high priority districts aren't taking up the responsibility of stabilising the IMR of the districts in their charge with as much concern and care as they should.Illiteracy in districts like Haridwar which has the worst IMR of 64 as per the recent survey is leading to more infant deaths.“

Uttar Pradesh

2016, Gorakhpur 18th worst in the world

`62 Of 1,000 Kids Die Soon After Birth’

If Gorakhpur were a country , it would have been among 20 nations with the highest infant mortality rate (IMR) in the world.

Data from health department shows 62 out of 1,000 children born in Gorakhpur die before turning one.Against this, 48 out of 1,000 die in UP and 40 out of 1,000 in India. But if compared to the global scale using data from the CIA's (Central Intelligence Agency , US) records, infant mortality rate of Gorakhpur is as high as of 20 countries with the highest IMR. “With an IMR of 62, Gorakhpur with 44.5-lakh population would be number 18, replacing the Republic of Gambia in West Africa, with a population of 19.18 lakh,“ said health activist Bobby Ramakant.

With IMR of 62.90 and 64.60, Zambia and South Sudan give competition to Gorakhpur. Topping the CIA list is Afganistan with an IMR of 112. Mali with 100, Somalia with 96, Central African Republic with 88 and Guinea Bissau with 87 follow on the subsequent ranks.

Gorakhpur's under-5 mortality is worse than the national and state average. While India's under-5 mortality rate is 50, against UP's rate of 62, Gorakhpur's fairs badly with 76. Health commentator Aarti Dhar said, “The high IMR is because of factors like malnutrition, incomplete immunisation, open defecation and unsafe drinking water.“

Citing the fourth national family health survey figures, she said over 35% kids in Gorakhpur are underweight, while 42% are stunted. The district also lags on the immunisation front--one in three kids don't complete the mandatory immunisation cycle.Only 35% households have toilets which suggests high rate of open defecation, resulting in 25% kids in the district suf fering from diarrhoea.

Paediatricians said malnutrition and incomplete immunisation make children vulnerable towards diseases like encephalitis. “Malnourished children have lower resistance to infection and are more likely to die from common childhood ailments like diarrhoeal diseases and respiratory infections,“ said professor Shally Awasthi, faculty member King George's Medical University .

Doctors at BRD Medical College, requesting anonymity, said 70% encephalitis-hit kids were malnourished.

2019

Rema nagarajan, March 22, 2023: The Times of India

From: Rema nagarajan, March 22, 2023: The Times of India