Irulas of the Nīlgiris

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Irulas of the Nīlgiris

In the Kotagiri bazaar, which is an excellent hunting-ground for the anthropologist, may be seen gathered together on market-day Kotas, Badagas, Kanarese, Irulas, Kurumbas, and an occasional Toda from the Kodanād mand. A tribal photograph was taken there, with the result that a deputation subsequently waited on me with a petition to the effect that “We, the undersigned, beg to submit that your honour made photos of us, and has paid us nothing. We, therefore, beg you to do this common act of justice.” The deputation was made happy with a pourboire.

In my hunt after Irulas, which ended in an attack of malarial fever, it was necessary to invoke the assistance and proverbial hospitality of various planters. On one occasion news reached me that a gang of Irulas, collected for my benefit under a promise of substantial remuneration, had arrived at a planter’s bungalow, whither I proceeded. The party included a man who had been “wanted” for some time in connection with the shooting of an elephant on forbidden ground. He, suspecting me of base designs, refused to be measured, on the plea that he was afraid the height-measuring standard was the gallows. Nor would he let me take his photograph, fearing (though he had never heard of Bertillonage) lest it should be used for the purpose of criminal identification. Unhappily a mischievous rumour had been circulated that I had in my train a wizard Kurumba, who would bewitch the Irulas, in order that I might abduct them (for what purpose was not stated).

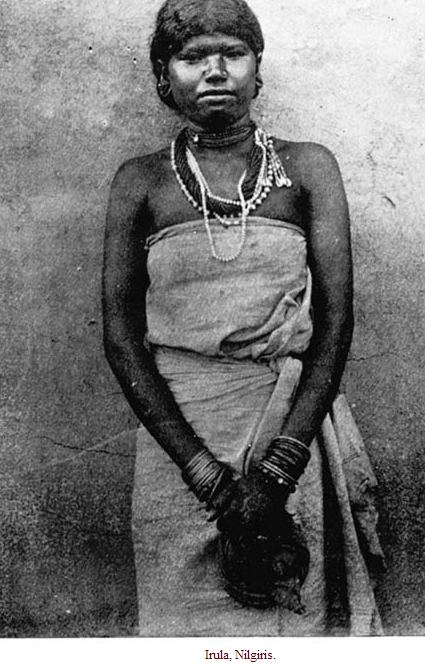

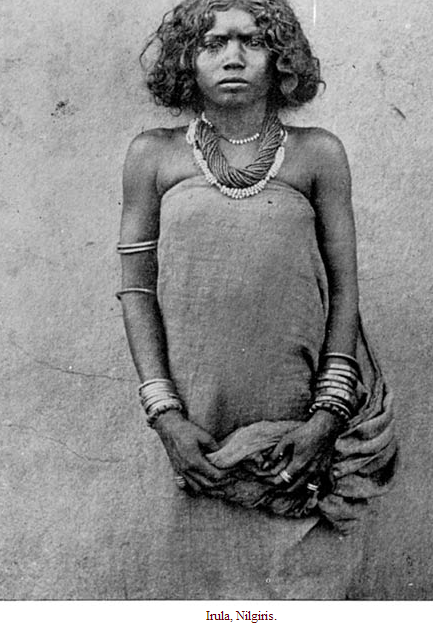

As the Badagas are the fairest, so the Irulas are the darkest-skinned of the Nīlgiri tribes, on some of whom, as has been said, charcoal would leave a white mark. The name Irula, in fact, means darkness or blackness (irul), whether in reference to the dark jungles in which the Irulas, who have not become domesticated by working as contractors or coolies on planters’ estates, dwell, or to the darkness of their skin, is doubtful. Though the typical Irula is dark-skinned and platyrhine, I have noted some who, as the result of contact metamorphosis, possessed skins of markedly paler hue, and leptorhine noses.

The language of the Irulas is a corrupt form of Tamil. In their religion they are worshippers of Vishnu under the name of Rangasvāmi, to whom they do pūja worship) at their own rude shrines, or at the Hindu temple at Karaimadai, where Brāhman priests officiate. “An Irula pūjāri,” Breeks writes, “lives near the Irula temples, and rings a bell when he performs pūja to the gods. He wears the Vishnu mark on his forehead. His office is hereditary, and he is remunerated by offerings of fruit and milk from Irula worshippers. Each Irula village pays about two annas to the pūjāri about May or June. They say that there is a temple at Kallampalla in the Sattiyamangalam tāluk, north of Rangasvāmi’s peak. This is a Siva temple, at which sheep are sacrificed. The pūjāri wears the Siva mark. They don’t know the difference between Siva and Vishnu. At Kallampalla temple is a thatched building, containing a stone called Māriamma, the well-known goddess of small-pox, worshipped in this capacity by the Irulas. A sheep is led to this temple, and those who offer the sacrifice sprinkle water over it, and cut its throat. The pūjāri sits by, but takes no part in the ceremony. The body is cut up, and distributed among the Irulas present, including the pūjāri.”

In connection with the shrine on Rangasvāmi peak, the following note is recorded in the Gazetteer of the Nīlgiris. “It is the most sacred hill on all the plateau. Hindu legend says that the god Rangasvāmi used to live at Karaimadai on the plains between Mettupālaiyam and Coimbatore, but quarrelled with his wife, and so came and lived here alone. In proof of the story, two footprints on the rock not far from Arakōd village below the peak are pointed out. This, however, is probably an invention designed to save the hill folk the toilsome journey to Rangasvāmi’s car festival at Karaimadai, which used once to be considered incumbent upon them. In some places, the Badagas and Kotas have gone even further, and established Rangasvāmi Bettus of their own, handy for their own particular villages.

On the real Rangasvāmi peak are two rude walled enclosures sacred to the god Ranga and his consort, and within these are votive offerings (chiefly iron lamps and the notched sticks used as weighing machines), and two stones to represent the deities. The hereditary pūjāri is an Irula, and, on the day fixed by the Badagas for the annual feast, he arrives from his hamlet near Nandipuram, bathes in a pool below the summit, and marches to the top shouting ‘Govinda! Govinda!’ The cry is taken up with wild enthusiasm by all those present, and the whole crowd, which includes Badagas, Irulas, and Kurumbas, surrounds the enclosures, while the Irula priest invokes the deities by blowing his conch and beating his drum, and pours oblations over, and decorates with flowers, the two stones which represent them. That night, two stone basins on the summit are filled with ghee and lighted, and the glare is visible for miles around. The ceremonies close with prayers for good rain and fruitfulness among the flocks and herds, a wild dance by the Irula, and the boiling (called pongal, the same word as pongal the Tamil agricultural feast) of much rice in milk. About a mile from Arakōd is an overhanging rock called the kodai-kal or umbrella stone, under which is found a whitish clay. This clay is used by the Irulas for making the Vaishnava marks on their foreheads at this festival.”

The following account of an Irula temple festival is given by Harkness. “The hair of the men, as well as of the women and children, was bound up in a fantastic manner with wreaths of plaited straw. Their necks, ears, and ankles were decorated with ornaments formed of the same material, and they carried little dried gourds, in which nuts or small stones had been inserted. They rattled them as they moved, and, with the rustling of their rural ornaments, gave a sort of rhythm to their motion. The dance was performed in front of a little thatched shed, which, we learnt, was their temple. When it was concluded, they commenced a sacrifice to their deity, or rather deities, of a he-goat and three cocks. This was done by cutting the throats of the victims, and throwing them down at the feet of the idol, the whole assembly at the same time prostrating themselves. Within the temple there was a winnow, or fan, which they called Mahri—evidently the emblem of Ceres; and at a short distance, in front of the former, and some paces in advance one of the other, were two rude stones, which they call, the one Moshani, the other Konadi Mari, but which are subordinate to the fan occupying the interior of the temple.”

A village near a coffee estate, which I inspected, was, at the time of my visit, in the possession of pariah dogs and nude children, the elder children and adults being away at work. The village was protected against nocturnal feline and other feral marauders by a rude fence, and consisted of rows of single-storied huts, with verandah in front, made of split bamboo and thatched, detached huts, an abundance of fowl-houses, and cucurbitaceous plants twining up rough stages. Surrounding the village were a dense grove of plantain trees, castor-oil bushes, and cattle pens.

When not engaged at work on estates or in the forest, the Irulas cultivate, for their own consumption, rāgi (Eleusine Coracana), sāmai (Panicum miliare), tenai Setaria italica), tovarai (Cajanus indicus), maize, plantains, etc. They also cultivate limes, oranges, jak fruit (Artocarpus integrifolia), etc. They, like the Kotas, will not attend to cultivation on Saturday or Monday. At the season of sowing, Badagas bring cocoanuts, plantains, milk and ghī (clarified butter), and give them to the Irulas, who, after offering them before their deity, return them to the Badagas. “The Irulas,” a recent writer observes, “generally possess a small plot of ground near their villages, which they assiduously cultivate with grain, although they depend more upon the wages earned by working on estates. Some of them are splendid cattle-men, that is, in looking after the cattle possessed by some enterprising planter, who would add the sale of dairy produce to the nowadays pitiable profit of coffee planting. The Irula women are as useful as the men in weeding, and all estate work. In fact, planters find both men and women far more industrious and reliable than the Tamil coolies.”

“By the sale of the produce of the forests,” Harkness writes, “such as honey and bees wax, or the fruit of their gardens, the Irulas are enabled to buy grain for their immediate sustenance, and for seed. But, as they never pay any attention to the land after it is sown, or indeed to its preparation further than by partially clearing it of the jungle, and turning it up with the hoe; or, what is more common, scratching it into furrows with a stick, and scattering the grain indiscriminately, their crops are, of course, stunted and meagre. When the corn is ripe, if at any distance from the village, the family to whom the patch or field belongs will remove to it, and, constructing temporary dwellings, remain there so long as the grain lasts. Each morning they pluck as much as they think they may require for the use of that day, kindle a fire upon the nearest large stone or fragment of rock, and, when it is well heated, brush away the embers, and scatter the grain upon it, which, soon becoming parched and dry, is readily reduced to meal, which is made into cakes. The stone is now heated a second time, and the cakes are put on it to bake. Or, where they have met with a stone which has a little concavity, they will, after heating it, fill the hollow with water, and, with the meal, form a sort of porridge. In this way the whole family, their friends, and neighbours, will live till the grain has been consumed. The whole period is one of merry-making. They celebrate Mahri, and invite all who may be passing by to join in the festivities. These families will, in return, be invited to live on the fields of their neighbours. Many of them live for the remainder of the year on a kind of yam, which grows wild, and is called Erula root. To the use of this they accustom their children from infancy.”

Some Irulas now work for the Forest Department, which allows them to live on the borders of the forest, granting them sites free, and other concessions. Among the minor forest produce, which they collect, are myrabolams, bees-wax, honey, vembadam bark (Ventilago Madraspatana), avaram bark (Cassia auriculata), deer’s horns, tamarinds, gum, soapnuts, and sheekoy (Acacia concinna). The forests have been divided into blocks, and a certain place within each block has been selected for the forest depot. To this place the collecting agents—mostly Shōlagars and Irulas—bring the produce, and then it is sorted, and paid for by special supervisors. The collection of honey is a dangerous occupation. A man, with a torch in his hand, and a number of bamboo tubes suspended from his shoulders, descends by means of ropes or creepers to the vicinity of the comb. The sight of the torch drives away the bees, and he proceeds to fill the bamboos with the comb, and then ascends to the top of the rock.

The Irulas will not (so they say) eat the flesh of buffaloes or cattle, but will eat sheep and goat, field-rats, fowls, deer, pig (which they shoot), hares (which they snare with skilfully made nets), jungle-fowl, pigeons, and quail (which they knock over with stones).

They informed Mr. Harkness that, “they have no marriage contract, the sexes cohabiting almost indiscriminately; the option of remaining in union, or of separating, resting principally with the female. Some among them, the favourites of fortune, who can afford to spend four or five rupees on festivities, will celebrate their union by giving a feast to all their friends and neighbours; and, inviting the Kurumbars to attend with their pipe and tabor, spend the night in dance and merriment. This, however, is a rare occurrence.” The marriage ceremony, as described to me, is a very simple affair. A feast is held, at which a sheep is killed, and the guests make a present of a few annas to the bridegroom, who ties up the money in a cloth, and, going to the bride’s hut, conducts her to her future home. Widows are permitted to marry again.

When an Irula dies, two Kurumbas come to the village, and one shaves the head of the other. The shorn man is fed, and presented with a cloth, which he wraps round his head. This quaint ceremonial is supposed, in some way, to bring good luck to the departed. Outside the house of the deceased, in which the corpse is kept till the time of the funeral, men and women dance to the music of the Irula band. The dead are buried in a sitting posture, with the legs crossed tailorwise. Each village has its own burial-ground. A circular pit is dug, from the lower end of which a chamber is excavated, in which the corpse, clad in its own clothes, jewelry, and a new cloth, is placed with a lamp and grain. The pit is then filled in, and the position of the grave marked by a stone. On the third day a sheep is said to be killed, and a feast held. The following description of an annual ceremony was given to me. A lamp and oil are purchased, and rice is cooked in the village. They are then taken to the shrine at the burial-ground, offered up on stones, on which some of the oil is poured, and pūja is done. At the shrine, a pūjāri, with three white marks on the forehead, officiates. Like the Badaga Dēvadāri, the Irula pūjāri at times becomes inspired by the god. Writing concerning the Kurumbas and Irulas, Mr. Walhouse says that “after every death among them, they bring a long water-worn stone (devva kotta kallu), and put it into one of the old cromlechs sprinkled over the Nilgiri plateau. Some of the larger of these have been found piled up to the cap-stone with such pebbles, which must have been the work of generations. Occasionally, too, the tribes mentioned make small cromlechs for burial purposes, and place the long water-worn pebbles in them.”

The following sub-divisions of the tribe have been described to me:—Poongkaru, Kudagar (people of Coorg), Kalkatti (those who tie stone), Vellaka, Devāla, and Koppilingam. Of these, the first five are considered to be in the relation of brothers, so far as marriage is concerned, and do not intermarry. Members of these five classes must marry into the Koppilingam sub-division. At the census, 1901, Kasuva or Kasuba was returned as a sub-caste. The word means workmen, in allusion to the abandonment of jungle life in favour of working on planters’ estates, and elsewhere.

It is recorded by Harkness that “during the winter, or while they are wandering about the forests in search of food, driven by hunger, the families or parties separate from one another. On these occasions the women and young children are often left alone, and the mother, having no longer any nourishment for her infant, anticipates its final misery by burying it alive. The account here given was in every instance corroborated, and in such a manner as to leave no doubt in our minds of its correctness.”

The following notes are abstracted from my case-book.

Man, æt. 30. Sometimes works on a coffee estate. At present engaged in the cultivation of grains, pumpkins, jak-fruit, and plantains. Goes to the bazaar at Mettupalaiyam to buy rice, salt, chillies, oil, etc. Acquires agricultural implements from Kotas, to whom he pays annual tribute in grains or money. Wears brass earrings obtained from Kotas in exchange for vegetables and fruit. Wears turban and plain loin-cloth, wrapped round body and reaching below the knees. Bag containing tobacco and betel slung over shoulder. Skin very dark.

Woman, æt. 30. Hair curly, tied in a bunch behind round a black cotton swab. Wears a plain waist-cloth, and print body-cloth worn square across breasts and reaching below the knees. Tattooed on forehead. A mass of glass bead necklaces. Gold ornament in left [382]nostril. Brass ornament in lobe of each ear. Eight brass bangles on right wrist; two brass and six glass bangles on left wrist. Five brass rings on right first finger; four brass and one tin ring on right forefinger.

Woman, æt. 25. Red cadjan (palm leaf) roll in dilated lobes of ears. Brass and glass bead ornament in helix of right ear. Brass ornament in left nostril. A number of bead necklets, one with young cowry shells pendent, another consisting of a heavy roll of black beads. The latter is very characteristic of Irula female adornment. One steel bangle, eight brass bangles, and one chank-shell bangle on right wrist; three lead, six glass bangles, and one glass bead bangle on left wrist. One steel and one brass ring on left little finger.

Woman, æt. 35. Wears loin-cloth only. Breasts fully exposed. Cap of Badaga pattern on head. Girl, æt. 8. Lobe of each ear being dilated by a number of wooden sticks like matches. Average stature 159.8 cm.; nasal index 85 (max. 100).