Islamabad: History

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Islamabad’s heritage

Cover Story: Nature’s riches

Who loves not the shady trees, The smell of flowers, the sound of brooks, The song of birds, and the hum of bees, Murmuring in green and fragrant nooks, The voice of children in the spring? Along the field-paths wandering?

— T. Millar

Islamabad, the capital of Pakistan, established on a site on the Potohar plateau in October 1961, has a long history dating back to pre-historic times. The river Soan (Golden) runs along its eastern side. On its northern and western sides spread out the hills of Margallah (‘Mar-i-Qila’, translated into Persian as ‘Margala’ or ‘serpent’s fort’) and Taxila (Takshasila, meaning ‘hill capital of the serpent king Taksha’) — the oldest capital of the region, which the Aryans called Gandhara. When Taxila on the western side of the hill was the capital, Islamabad on the eastern side was the suburb; now with Islamabad the capital, Taxila is the suburb.

The Taxila region was part of the vibrant culture of Gandhara, in which the pursuit of knowledge flourished at the ancient University of Taxila. This co-existed with the prosperous trade along the route that linked Central Asia with the Indo-Gangetic plain. Through trade the Gandharans became acquainted with the arts and crafts of people of both east and the west. They evolved their individual style by synthesising all of them, thus contributing to the evolution of Gandhara art and civilisation.

Margallah reflects events of the past. These are echoed in materials excavated in Islamabad, which present us with the continuous story of the people who lived here, as they came in contact with others, and as they assimilated and integrated various trends into a cultural pattern which we call Gandharan today. At the centre of the story lies the historic city of Taxila-heir to the past glory of Gandhara and focal centre for humanity coming from East and West.

Interpretation of the pre-historic records of the Old Stone age has been assisted by the find of the oldest stone tool, dating back 2.2 million years, on an old terrace of the Soan near a place called Rawat. This discovery has superseded the record of the African Stone age period; thus, Islamabad has become the oldest living place in the world. The region bears evidence of the following historical periods: Early, Middle and Late Paleolithic ages; Neolithic age; Gandhara Grave Culture and Painted Grey Ware Culture, as well as Achaemenian, Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim, Gakkhar, Sikh and British periods...

At almost 47 years, Islamabad is a young city in a region in need of more urban centres. Cities present opportunities for employment, for healthcare, for communal organisation and for education. Islamabad is one of the few cities in a region where organised urbanisation is a must to meet the basic needs of the majority of the population...

Living in Islamabad for the past 32 years, I have seen the best of nature; shady trees, the sound of brooks, the song of birds, the humming of bees and the murmuring in the green, fragrant nooks of this beautiful city. It has been a pleasure growing up in one of the most beautiful cities in this part of the world; its natural beauty is what we in Islamabad have always relished. All year round we witness a riot of colours, starting from the yellow of jasmine flowers in February, the pink, mauve and white blossom of Kachnaar in April, and the deep blue mauve of Jacaranda in May along with the crimson of Flame of the Forest. June and July are filled with the streaming gold of Amaltas while monsoon brings out the brightest shades of green in the trees as the clouds play hide and seek over the lush Margallah Hills. Autumn has its own special hues of red, orange brown in the leaves of Shisham and Chinaar. Vermillion flowers of Poinsettia and their evergreen leaves give colour to dull grey winter days. This is a city of varied and beautiful trees.

All credit goes to the Capital Development Authority (CDA) for planting most of the trees we see in Islamabad. Except for the folly of aerial seeding an alien species, Paper Mulberry, the pioneers have done a great job. The stately row of Pipal trees along one of the oldest roads, the Khayaban-i-Suhrawardy past Aabpara market is a splendid sight. Even a new sector of F-11 has rows upon rows of Amaltas and Jacaranda trees. One is grateful to the hardworking maalis (gardeners) for the tender loving care that has given us this visual treat.

Trees are not only the identity of Islamabad; they are its heritage too. We have inherited a number of Banyan (ficus indica) and Pipal (ficus religiosa) trees. Both of these species are a variation of fig trees and among the eight or so species of trees considered sacred in the subcontinent. Some magnificent ancient wild Mango trees are also part of the heritage. While the new trees planted after Islamabad was built can be replaced, the grand old Banyans and Pipals are irreplaceable. It takes centuries for a Banyan or Pipal to mature, thus the destruction of these trees is the loss of centuries of history.

Islamabad is evolving and in the past few years the ‘development process’ has accelerated considerably. Over 20,000 trees have been felled as part of this process; the result has been a huge loss of natural beauty. Thanks to my digital camera, I have been able to preserve some of this through a picture record of old trees. It was in the process of looking for these trees in the greenest nooks that I found the captivating mystical and historical side of Islamabad.

Islamabad has long been known as a ‘dead city’ by those who do not live here. While the new city of Islamabad has been struggling to develop its own culture, the land it is situated on has always had a soul, a history, culture and traditions. Unfortunately, this heritage had either been lost altogether in the ‘development process’, or else is in an appalling condition. The city is struggling to find its soul.

The city’s planners have so far been insensitive towards conserving the past for tourists or those of us interested in what this place looked like before Islamabad was built. In the developed sectors of the city, the bulldozers and cranes have wiped out all traces of history or heritage. Many a Banyan tree has been razed to the ground, knowing that in civilised countries old trees are part of the national heritage. It is only in the undeveloped sectors of Islamabad that one still finds clumps of indigenous trees.

However, there are a few instances where old trees have been spared for example, the Banyan near the officer’s mess in Pakistan Airforce Colony in E-9, Banyan near Ali Medical Center in F-8 and the one in front of the Nursing school of Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences in G-8.

Islamabad was built in 1961 according to a master plan made by the Greek town planner C.A. Doxiadus. He belonged to Athens where the ancient ruins of the Acropolis, over 2000 years old, are proudly displayed for tourists to enjoy. However, while making the master plan, it seems that the protection of heritage was not a priority for the planners, local or international. If Doxiadus had marked heritage sites as special areas, it would have helped. As a result, the few priceless heritage sites left in this area suffer from neglect and their potential as a cultural tourist attraction has not been fully recognised.

The Field Survey Report on the Palaeolithic Sites in the Rawalpindi District, published in 1968 by the department of Archaeology, mentions only five rock shelters in this region. Alas, none was declared protected under the Antiquities Act of 1975, nor have any steps been taken to protect them since.

Dr Dani, through his research, has always reminded us of the millennium-rich history of Islamabad. Unfortunately, the CDA, Federal Archaeology Department and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism have so far failed to preserve the places Dr Dani has identified. Most of the sites here should have been protected under the 1975 Antiquities Act.

Archaeologist Dr M. Salim of the Taxila Institute of Asian Civilisations (TIAC), Quid-i-Azam University, Islamabad warned us in 1989 about the destruction of Islamabad’s rich cultural heritage.

Recently various housing schemes have accelerated the process of destruction of these ancient sites by levelling and construction. Once the new buildings are erected, nothing can be done. We hope that various government and non-government agencies would come forward to help save ancient Islamabad from the bulldozers.

In the same article, Dr M. Salim mentions Palaeolithic (a period that lasted from two million to ten thousand years ago, of or relating to the old and new Stone age) caves at Jori Rajgan in the Margallah Hills. The nearby FECTO cement factory was set up in the mid ’80s during President Zia ul Haq’s regime. Unfortunately, the constant blasting of the factory in the Margallah Hills continues to cause irreparable damage to these caves and research work carried out by the TIAC research team is hampered.

In 1977, Dr M. Salim discovered Dhok Gangaal, a Painted Grey Ware (PGW) site near Chaklala, outside Islamabad. It remained unexplored until March 1989 when Dr M. Salim and F.B. Lyon collected PGW pottery from one of the mounds. The period between late Gandhara Grave Culture (circa 1600 BC and flourishes in Gandhara circa 1500 BC to 500 BC) and the Buddhist period is less well known. However, the investigation of the site of Dhok Gangaal provides some information about this period.

The site is one and a half kilometers from Chaklala and 5 kilometres from Faizabad. A mound on the main airport road, is known to many residents of Islamabad and Rawalpindi as it boasts the large inscriptions in English and Urdu — Faith, Unity and Discipline — the famous words spoken by Quaid-i-Azam, M. Ali Jinnah, at the time of Pakistan’s independence. In the same article, Dr. M. Salim urges the preservation of this important site for education, research and cultural tourism purposes but recently a large portrait of Quaid-i-Azam has been erected on the top of the mound.

More than a decade later, like Dr M. Salim, many plead for the protection and preservation of the historical assets of Islamabad as part of the development process; otherwise, Islamabad will lose all traces of its Potohar heritage.

I have always been interested in knowing more about the people who lived in the small villages before Islamabad was built. To this end, I have photographed the villagers. I have met in Saidpur and other villages and have recorded some of the rich traditions and culture of these people of the Potohar plateau. They will be leaving their ancestral homes very soon, just like many before them, uprooted and relocated as part of the ‘development process’. I have taken most of these photographs during picnics with my children, which were meant to show them the beautiful historical aspect of their city.

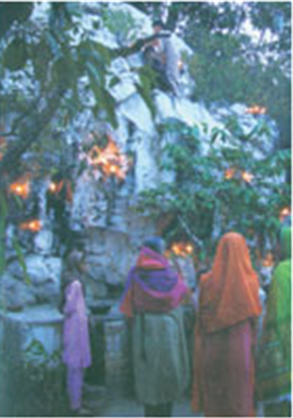

Wherever we went, we found that at the heart of each site are old Banyan or Pipal trees. We found Banyans at Sufi saints’ shrines, and Pipal trees growing near Hindu temples. Revolving around these trees are old traditions and practices, reminding us of the Potohar plateau’s spiritual heritage. Every Thursday in Islamabad, people who find solace in centuries old traditions, light diyaas or cheragh (oil-lamps), burn incense and hang coloured flags around old trees.

It was under the Pipal tree near the town of Gaya, Bihar, in India that Buddha achieved the great enlightenment. Buddhism, according to archaeologist Walter A. Fairservis Jr., in his book Roots of Ancient India, seems to be a protest against and a direction out of a complex way of urban life in which ambition, social inequality, civil strife, hunger, disease, temptation, superstition, riches, poverty and the like prevail. Buddha’s discovery was made under a Pipal tree. In the green valleys of the Margallah Hills, there are a number of remains of Buddhist monasteries. Pipal and Banyan trees mark these spots.

Trees had a special significance for the Sufi saints of the Potohar plateau as well. This region is home to Islamic mysticism and the Margallah Hills are dotted with Sufi shrines. Some orders of Sufi saints recommend retreating to the solitude of nature, which is what saints like Barri Imam did. He spent 24 years of his life in the forests of Hazara, remembering Allah. The spiritual legacy of such saints echoes in the old Banyans of Islamabad.

Ancient seals derived from Indus Valley Civilisation reveal that the Harappans worshipped Pipal trees. According to anthropologist Dr Jurgen Wasim Frembgen, the symbol of the ‘tree of life’ has had significance since antiquity. It is an extremely important symbol and is reflected in hearts throughout the Near East and South Asia.

While the new trees planted after the birth of Islamabad by the CDA, non-governmental organisations and citizens’ groups are indeed a joy, the old trees are a reminder of a time of respect for other religions, traditions and, most of all, respect for Mother nature. Many of us in Islamabad long for the time when this land was one of religious plurality and tolerance. Through these photographs, I want to share with the readers the natural beauty and the heritage sites of Islamabad that I have cherished and enjoyed for all these years. Through them, I hope that citizens and the city’s fathers will be inspired to take steps to protect and preserve them.

Islamabad History

Capital Development Authority, Islamabad

The capital city of Pakistan, Islamabad is located in the northwest of the country on Potohar Plateau. This area has been significant in history for being a part of the crossroads of the Rawalpindi and the North West Frontier Province. The city was built in 1960 to replace Karachi as the Pakistani capital, which it has been since 1963. Due to Islamabad's proximity to Rawalpindi, they are considered sister cities.

Compared to other cities of the country, Islamabad is a clean, spacious and quiet city with lots of greeneries. The site of the city has a history going back to the earliest human habitations in Asia. This area has seen the first settlement of Aryans from Central Asia, ancient caravans passing from Central Asia, and the massive armies of Tamerlane and Alexander.

To the north of the city you will find the Margalla Hills. Hot summers, monsoon rains and cold winters with sparse snowfall in the hills almost summarize the climate of this area. Islamabad also has a rich wildlife ranging from wild boars to leopards.

After the formation of Pakistan in 1947, it was felt that a new and permanent Capital City had to be built to reflect the diversity of the Pakistani nation. It was considered pertinent to locate the new capital where it could be isolated from the business and commercial activity of the Karachi, and yet is easily accessible from the remotest corner of the country. A commission was accordingly set in motion in 1958, entrusted with the task of selecting a suitable site for the new capital with a particular emphasis on location, climate, logistics and defense requirements, aesthetics, and scenic and natural beauty.

After extensive research, feasibility studies and a thorough review of various sites, the commission recommended the area North East of the historic garrison city of Rawalpindi. After the final decision of the National Cabinet, it was put into practice. A Greek firm, Doxiadis Associates devised a master plan based on a grid system, with its north facing the Margallah Hills. The long-term plan was that Islamabad would eventually encompass Rawalpindi entirely, stretching to the West of the historic Grand Trunk road.

Islamabad nestles against the backdrop of the Margallah Hills at the northern end of Potohar Plateau. Its climate is healthy, pollution free, plentiful in water resources and lush green. It is a modern and carefully planned city with wide roads and avenues, elegant public buildings and well-organized bazaars, markets, and shopping centers. The city is divided into eight basic zones: Administrative, diplomatic enclave, residential areas, educational sectors, industrial sectors, commercial areas, and rural and green areas.

The metropolis of Islamabad today is the pulsating beat of Pakistan, resonating with the energy and strength of a growing, developing nation. It is a city, which symbolizes the hopes and dreams of a young and dynamic nation and espouses the values and codes of the generation that has brought it thus far. It is a city that welcomes and promotes modern ides, but at the same time recognizes and cherishes its traditional values and rich history.

Islamabad: Ojhri Camp disaster, 1988 (history)

20 years on, Ojhri Camp truth remains locked up

By Amir Wasim

ISLAMABAD, April 9: Twenty years have passed but the images of destruction caused by the Ojhri Camp disaster are still fresh in the minds of many residents of Rawalpindi and Islamabad.

Over 100 men, women and children were killed and many times more were wounded by the missiles and projectiles which exploded mysteriously and rained death and destruction on the twin cities on this day in 1988.

Physical scars of the tragedy may have healed but the nation is unaware till this day what, and who, caused that disaster and why. An investigation was conducted into the disaster but, like in the case of all other probes into national tragedies, its report was not made public.

The then prime minister Mohammad Khan Junejo appointed two committees, one military and the other parliamentary, to probe the military disaster. His action so infuriated military dictator Gen Ziaul Haq that he dismissed his handpicked prime minister on May 29, 1988 - the main charge being that he failed to implement Islam in the country.

While the parliamentary committee, headed by old politician Aslam Khattak, went out with the Junejo government, the military committee under Gen Imranullah Khan submitted its report before the government’s dismissal.

Subsequent governments of prime ministers Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif which followed Gen Zia’s fiery death in a mysterious plane crash on August 17, 1988, also kept Gen Imranullah Khan’s findings under covers.

Some opposition members called for making it public during the last five years of Gen Pervez Musharraf’s military rule but the PML-Q government took the position that it would not be “in the larger national interest”.

Neither political observers expect the PPP and the PML-N doing so even when they have been swept into power again by the people and run a coalition government.

Interestingly, when contacted, leaders of both the parties agreed that the Ojhri Camp inquiry report should be made public but refused to commit to do so.

Junejo’s defence minister Rana Naeem Ahmed had told Dawn in an interview last year that he had received the report but said it did not fix responsibility on any one and declared the huge disaster an accident.

Even then the ISI seized it in a raid on his office the day after the Junejo government was dismissed, he claimed.

“They returned all my belongings, except the briefcase that contained the report,” he said, disclosing that the report was inconclusive and focused just on the causes of the blast.

It was a bright and sunny morning on April 10, 1988, when the citizens of Islamabad and Rawalpindi were startled by huge explosions and swishing sounds as if fireworks were going off.

Thousands of missiles and projectiles soon started raining down on the two cities the Ojhri Ammunition Depot, situated in the densely-populated Faizabad area, blew up.

Officially the death toll was 30, but independent estimates put the figure much higher. Prominent among those killed was a federal minister Khaqan Abbasi whose car was hit by a flying missile while he was on his way to Murree, his hometown.

His son accompanying him was hit in the head. He went into deep coma and died some two years ago after remaining on artificial respiration for 17 years.

The Ojhri Camp was used as an ammunition depot to forward US-supplied arms to Afghan Mujahideen fighting against the Soviet forces in Afghanistan. There were reports that a Pentagon team was about to arrive to take audit of the stocks of the weapons and that allegedly the camp was blown up deliberately to cover up pilferage from the stocks.

Some reports said that Ojhri Camp had about 30,000 rockets, millions of rounds of ammunition, vast number of mines, anti-aircraft Stinger missiles, anti-tank missiles, multiple-barrel rocket launchers and mortars worth $100 million in store at the time of blasts that destroyed all records and most of the weapons thus making it impossible for anyone to check the stocks.

Prime minister Junejo had promised to the National Assembly that the inquiry report would be made public and the guilty would be punished but was sacked by Gen Zia.

Senior members of the PPP and the PML-N admit that their governments in the past made no serious effort to make the report public.

A PPP member however claimed that the second Benazir Bhutto government did attempt to do that but failed due to resistance from the “concerned quarters”. There are some elements in the Charter of Democracy, signed by the PPP and the PML-N, which could be pursued to make such reports public, he said.

Naming the roads of Islamabad

What’s in a name? A road to fame!

ISLAMABAD has undergone major transformation in the last few years with the construction of a new road network that has, to a large extent, changed the capital’s landscape.

As well as ease the traffic blues, these carpeted avenues have added to the glitter of what is decidedly, the best planned city in Pakistan and one of the world’s most picturesque capitals.

More recently, two avenues have linked up the entire capital, one of them running directly into twin Rawalpindi as well.

However, not everyone is happy about the christening of the Ninth Avenue. It has been named after former foreign minister Agha Shahi. No-one knows for sure what criteria was employed to make a national recall for Shahi.

Questions have been raised if the honour bestowed on Shahi was not for mere longevity of service. Some have defended Shahi’s term as a bright period for the usually staid Foreign Office and others, who agreed that imposing his name was a questionable move.

The mandarins of the Capital Development Authority (CDA) have never really made an effort to enlighten the denizens of Islamabad on how they determine which road, street, flyover, underpass or a roundabout is named after whom and why.

Perhaps, it is just the nature of the beast: In Islamabad, secrecy is the standard operating procedure, which leads to a deliberate state of inertia to offset any criticism.

In countries, which espouse the virtues of open debate as well as accountability, public avenues cannot be named on whim or personal like. It would make sense for a representative council or committee of citizens to have a say in these matters.

If the CDA’s idea was to name the avenue strictly after a foreign minister, there were certainly candidates more deserving than the long serving Shahi even amongst those still living.

However, presuming that we usually take to honouring people only posthumously, there was and still is a strong case for more illustrious names.

For instance, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto dwarfs most of them even purely as a foreign minister — one of the most distinguished foreign ministers Pakistan has had.

Both times in his stint as foreign minister from 1963-1966 and then 1971-1977 (during which time, as President and then PM, he retained the Foreign Ministry before eventually appointing Aziz Ahmed), Bhutto emerged as the architect of a truly independent foreign policy, which, in the first instance, led to his falling out with military ruler Ayub Khan.

Space constraints do not permit to recount his achievements as even foreign minister but since he overgrew that role to become a giant leader, he deserves a trite more than just naming an avenue after him in the city of bureaucrats.

Therefore, two well-rounded candidates emerge: Sir Muhammad Zafrullah Khan, the country’s first foreign minister, and Aziz Ahmed (not to be confused with the last Pakistani envoy to New Delhi).

Both served with distinction well before they were given the highest office in the Foreign Ministry. But a comparison would perhaps, be unfair, given the knighted Zafrullah’s highly distinguished career and role as author of the newborn state’s foreign policy.

Picked by the Father of the Nation, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Zafrullah had already made his presence felt by forcefully arguing the case of Muslims in 1947 before the Radcliffe Boundary Commission — at Mr Jinnah’s instance. In October of the same year, he represented Pakistan at the UN General Assembly and advocated the Muslim world’s stand on the Palestinian issue.

He showed his mettle in the seven years he remained the custodian of foreign policy with a flourish for even international issues that raised Pakistan’s profile.

Zafrullah’s efforts materialised into the UN resolutions on Kashmir, which are the basis of the Pakistan’s case and grievance.

Later, he became the first Asian president of the International Court of Justice in The Hague. He also served briefly as the President of the UN General Assembly.

Aziz Ahmed, on the other hand, is credited with building strong ties with the US that characterized the Eisenhower and Kennedy Administrations of the Sixties. He gained prominence following the 1965 war with India and his vocal opposition to the Tashkent Declaration. Called out of retirement by Bhutto, he later played a key role in negotiating the famous Simla Agreement.

Among others, Liaquat Ali Khan (more renowned as the first prime minister), Feroze Khan Noon (post-Independence), Gohar Ayub (N-blasts) and Khurshid Kasuri (post 9/11) also served as FMs at turning points in our history but not necessarily, with any discerning acclaim.

In a nutshell, Sir Zafrullah and Aziz Ahmed had better credentials for riding the Ninth Avenue.

The writer is News Editor at Dawn News. He may be contacted at kaamyabi@gmail.com