Jōgi

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

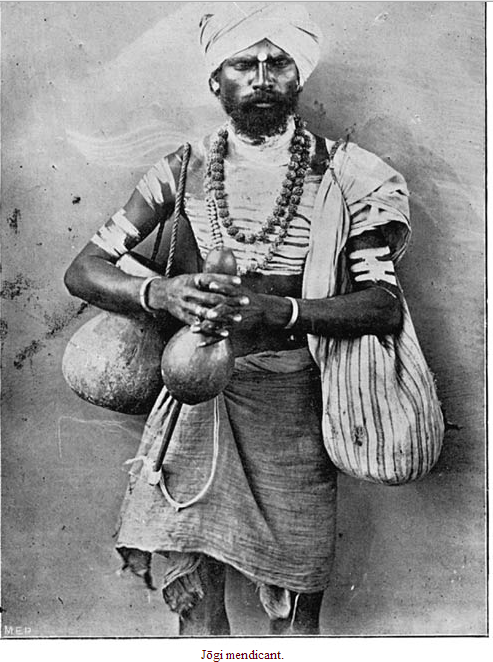

Jōgi

The Jōgis, who are a caste of Telugu mendicants, are summed up by Mr. H. A. Stuart as being “like the Dāsaris, itinerant jugglers and beggars. They are divided into those who sell beads, and those who keep pigs. They are dexterous snake-charmers, and pretend to a profound knowledge of charms and medicine. They are very filthy in their habits. They have no restrictions regarding food, may eat in the house of any Sūdra, and allow widows to live in concubinage, only exacting a small money penalty, and prohibiting her from washing herself with turmeric-water.” In addition to begging and pig-breeding, the Jōgis are employed in the cultivation of land, in the destruction of pariah dogs, scavenging, robbery and dacoity. Some of the women, called Killekyāta, are professional tattooers. The Jōgis wander about the country, taking with them (sometimes on donkeys) the materials for their rude huts. The packs of the donkeys are, Mr. F. S. Mullaly informs us, “used as receptacles for storing cloths obtained in predatory excursions. Jōgis encamp on the outskirts of villages, usually on a plain or dry bed of a tank. Their huts or gudisays are made of palmyra leaves (or sedge) plaited with five strands forming an arch.” The huts are completely open in front.

In the Tamil country, the Jōgis are called Dhoddiyan or Tottiyan (q.v.), and those who are employed as scavengers are known as Koravas or Oddans. The scavengers do not mix with the rest of the community. Some Jōgis assert that they have to live by begging in consequence of a curse brought on them by Parvati, concerning whose breasts one of their ancestors made some indiscreet remarks. They consider themselves superior to Mālas and Mādigas, but an Oddan (navvy caste) will not eat in the house of a Jōgi. They are said to eat crocodiles, field rats, and cats. There is a tradition that a Jōgi bridegroom, before tying the bottu (marriage badge) on his bride’s neck, had to tie it by means of a string dyed with turmeric round the neck of a female cat. People sometimes object to the catching of cats by Jōgis for food, as the detachment of a single hair from the body of a cat is considered a heinous offence. To overcome the objection, the Jōgi says that he wants the animal for a marriage ceremony. On one occasion, I saw a Mādiga carrying home a bag full of kittens, which, he said, he was going to eat.

The Jōgi mendicants go about, clad in a dirty loin-cloth (often red in colour) and a strip of cloth over the shoulders, with cobras, pythons, or rat snakes in baskets, and carrying a bag slung over the shoulder. The contents of one of these bags, which was examined, were fruits of Mimusops hexandra and flower-spikes of Lippia nodiflora (used for medicine), a snake-charming reed instrument, a piece of cuttle-fish shell, porcupine quills (sold to goldsmiths for brushes), a cocoanut shell containing a powder, narrikombu (spurious jackals’ horns) such as are also manufactured by Kuruvikārans, and two pieces of wood supposed to be an antidote for snake-poisoning. The women go about the streets, decorated with bangles and necklaces of beads, sharks’ vertebræ, and cowry shells, bawling out “Subbamma, Lachchamma,” etc., and will not move on till alms are given to them. They carry a capacious gourd, which serves as a convenient receptacle for stolen articles. Like other Telugu castes, the Jōgis have exogamous septs or intipēru, of which the following are examples:—

• Vagiti, court-yard.

• Uluvala, horse-gram.

• Jalli, tassels of palmyra leaves put round the necks of bulls.

• Vavati (relationship).

• Gundra, round.

• Bindhollu, brass water-pot.

• Cheruku, sugar-cane.

• Chappadi, insipid.

• Boda Dāsiri, bald-headed mendicant.

• Gudi, temple.

At the Mysore census, 1901, Killekyāta, Helava, Jangaliga, and Pākanāti were returned as being Jōgis. A few individuals returned gōtras, such as Vrishabha, Kāverimatha, and Khedrumakula. At the Madras census, Siddaru, and Pāmula (snake) were returned as sub-castes. Pāmula is applied as a synonym for Jōgi, inasmuch as snake-charming is one of their occupations.

The women of the caste are said to be depraved, and prostitution is common. As a proof of chastity, the ordeal of drinking a potful of cow-dung water or chilly-water has to be undergone. If a man, proved guilty of adultery, pleads inability to pay the fine, he has to walk a furlong with a mill-stone on his head. At the betrothal ceremony, a small sum of money and a pig are given to the bride’s party. The pig is killed, and a feast held, with much consumption of liquor. Some of the features of the marriage ceremony are worthy of notice. The kankanams, or threads which are tied by the maternal uncles to the wrists of the bride and bridegroom, are made of human hair, and to them are attached leaves of Alangium lamarckii and Strychnos Nux-vomica. When the bridegroom and his party proceed to the bride’s hut for the ceremony of tying the bottu (marriage badge), they are stopped by a rope or bamboo screen, which is held by the relations of the bride and others. After a short struggle, money is paid to the men who hold the rope or screen, and the ceremonial is proceeded with. The rope is called vallepu thadu or relationship rope, and is made to imply legitimate connection. The bottu, consisting of a string of black beads, is tied round the bride’s neck, the bride and bridegroom sometimes sitting on a pestle and mortar. Rice is thrown over them, and they are carried on the shoulders of their maternal uncles beneath the marriage pandal (booth). As with the Oddēs and Upparavas, there is a saying that a Jōgi widow may mount the marriage dais (i.e., remarry) seven times.

When a girl reaches puberty, she is put in a hut made by her brother or husband, which is thatched with twigs of Eugenia Jambolana, margosa (Melia Azadirachta), mango (Mangifera Indica), and Vitex Negundo. On the last day of the pollution ceremony the girl’s clothes and the hut are burnt.

The dead are always buried. The corpse is carried to the burial-place, wrapped up in a cloth. Before it is lowered into the grave, all present throw rice over the eyes, and a man of a different sept to the deceased places four annas in the mouth. Within the grave the head is turned on one side, and a cavity scooped out, in which various articles of food are placed. Though the body is not burnt, fire is carried to the grave by the son. Among the Jalli-vallu, a chicken and small quantity of salt are placed in the armpit of the corpse. On the karmāndhiram, or day of the final death ceremonies, cooked rice, vegetables, fruit, and arrack are offered to the deceased. A cloth is spread near the grave, and the son, and other agnates, place food thereon, while naming, one after the other, their deceased ancestors. The food is eaten by Jōgis of septs other than the Jalli-vallu, who throw it into water. If septs other than the Jalli were to do this, they would be fined. Those assembled proceed to a tank or river, and make an effigy in mud, by the side of which an earthen lamp is placed. After the offering of cooked rice, etc., the lamp and effigy are thrown into the water. A man who is celebrating his wife’s death-rites then has his waist-thread cut by another widower while bathing. The Jōgis worship Peddavādu, Malalamma, Gangamma, Ayyavāru, Rudramma, and Madura Vīrudu.

Some women wear, in addition to the marriage bottu, a special bottu in honour of one of their gods. This is placed before the god and worn by the eldest female of a family, passing on at her death to the next eldest.

As regards the criminal propensities of the Jōgis, Mr. Mullaly writes as follows. “On an excursion being agreed upon by members of a Joghi gang, others of the fraternity encamped in the vicinity are consulted. In some isolated spot a nīm tree (Melia Azadirachta) is chosen as a meeting place.

Here the preliminaries are settled, and their god Perumal is invoked. They set out in bands of from twelve to fifteen, armed with stout bamboo sticks. Scantily clad, and with their heads muffled up, they await the arrival of the carts passing their place of hiding. In twos and threes they attack the carts, which are usually driven off the road, and not unfrequently upset, and the travellers are made to give all they possess. The property is then given to the headman of the gang for safe-keeping, and he secretes it in the vicinity of his hut, and sets about the disposal of it. Their receivers are to be found among the ‘respectable’ oil-mongers of 11 villages in the vicinity of their encampments, while property not disposed of locally is taken to Madras. Readmission to caste after conviction, when imprisonment is involved, is an easy matter. A feed and drink at the expense of the ‘unfortunate,’ generally defrayed from the share of property which is kept by his more fortunate kinsfolk, are all that is necessary, except the ceremony common to other classes of having the tongue slightly burnt by a piece of hot gold. This is always performed by the Jangam (headman) of the gang. The boys of the class are employed by their elders in stealing grain stored at kalams (threshing-floors), and, as opportunity offers, by slitting grain bags loaded in carts.” Jōgi.—A sub-division of Kudubi.