Jain: Deccan

Contents |

Jain

This article is an extract from THE CASTES AND TRIBES OF H. E. H. THE NIZAM'S DOMINIONS BY SYED SIRAJ UL HASSAN Of Merton College, Oxford, Trinity College, Dublin, and Middle Temple, London. One of the Judges of H. E. H. the Nizam's High Court of Judicature : Lately Director of Public Instruction. BOMBAY THE TlMES PRESS 1920 Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees |

Jain — a religious sect supposed to have been originally evolved from Buddhism and owing its elevation to the suppression of the latter faith. In later times it leaned towards Brah- manism, to which it conformed in its recognition of tjfe orthodox pantheon and its deference to the Vedas, to the rites derivable from them, to the institutions of caste and to the Brahmans as ministrant priests. This was rather a political move and probably saved the Jains from the persecution of the Brahmans, who successfully opposed and ultimately expelled the once potent faith of Buddhism from the country.

Origin and History

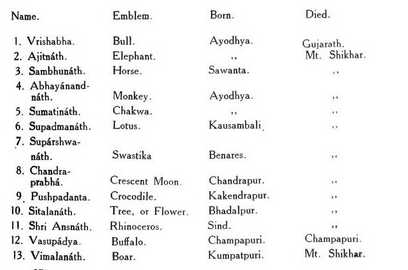

The origin of the Jain faith is involved in the obscurity which enshrouds all history of remote antiquity. It is said to have been founded by Rishabha Deva, the first of their Tirthankars, who is identified by some with the king Rishabha, mentioned in the BhdgWat Purdna ; but no direct evidence is adduced m corroboration of the statement. The influence of the faith as a popular religion may be traced to the sixth or seven centuries A. D. and continued till the twelfth, when it reached the zenith of its prosperity and included, among its votaries, some power- ful sovereigns of India, such as Kumarpal of Gujarath, Amogha Vaisha of Tandai Mandalam in Malabar, Kuna Pandya of Madura, Vishnu Vardhan of Mysore and King Vijala of Kalayani in Gulbarga. The noblest architectural monuments of the Jains, diffused throughout India, and the splendid temples sacred to their Tirthankars, belong to this period and bear overwhelming testimony to their influence during this time. The power of the Jains has since been on the decline and the sect scarcely numbers at the present day more than a million people.

The Jains are found in considerable numbers in Hyderabad Territory. They probably came into these Dominions from

Gujarath, Marwar and Southern India, where they were greatly patronised by the ruling dynasties ; but the date of their immigration cannot be ascertained.

Tenets

Vedas, reverence certain saints called Tirthankars who acquire, by practices of self-deniil and mortification, a station superior to that of gods and show extreme regard for animal life. The Vedas are admitted and quoted as an authority, but only so far as the doc- trines they ti^ch are conformable to Jain tenets. They admit the existence of twenty-four Tirthankars, or Jins, but confine their reverence to the last two, Parasnath and Mahavira or Vardhaman. The Jin is regarded as a veritable deity and is endowed with divine attributes. He is Jagat Prabhu (Lord of the World), Kshina Karma (free from bodily or ceremonial acts), Sarvadnya (omniscient), Adhish- wara (Supreme Lord), Devadhi Deva (God of Gods), Tirthankar (one who has frossed the worldly ocean), Kavali (the possessor of a spiritual nature), Arhat (entitled to the homage of gods and men), and Jina (the victor over all human passions and infirmities. The statues of the Jinas, usually of white or black marble, are enshrined in the temples of the sect.

According to the Jains, all existence is divisible into two heads — jioa (life), or the living and sentient principle, and ajioa (inertia), or the various modifications of inanimistic matter. These are imperish- able, though their forms and conditions may change. With them dharma is virtue and adharma is vice.

The Jains are divided into two leading branches • ' Digambaras ' or ' sky clad ' (naked), and ' Shwaitambaras ' or ' white robed.' At the present day the Digambaras do not go about naked, except at meal times, but wear coloured garments. The Shwaitambaras deck their images with jewels and clothes, while the Digambaras leave their images without clothes and ornaments. The Digambaras assert that women never attain Nirvana, but the Shwaitambaras admit the gentler sex to final annihilation. Two other sects have lately sprung up : the Dhundiyas, who affect rigorous adherence to the moral code, but disregard all forms of praise or prayer and ail modes of external worship, and the Tirapanthis, who deny the supremacy of a guru and present no perfumes, flowers or fruits to the images of the Tirthankars.

There are clerical as well as lay Jains, the Yati or Jati, ana the Shravaka, the former of whom lead a religious life and subsist on alms which the latter supply. The Yatis acknowledge obedience to the head of the matha (pasala) of which they are the members. They do not officiate as priests in the temples, the ceremonies being conducted by a Brahman trained for the purpose. They carry a broom, to sweep the ground before they tread upon it, and do not eat or drink in the dark, lest they should swallow an insect. Most of the Jatis act as physicians, and pretend to skill in palmistry and the black art. The secular Jains follow the usual professions of the Hindus. Some of them are engaged as merchants and bankers and form a very opulent portion of the community ; it is said that more than half of the mercantile wealth of India passes through the hands of the Jain laity. Although their objects of worship are the Tirthankars, they do not deny the existence of the Hindu gods, but pay their devotion to some of them. They visit a temple daily, where the image of amy of the last two ]ins is erected, walk round the image three times, make an offering of fruits and flowers and sing praises in honour of the saint.

The Jains have five great places of pilgrimage, to which large bands of pilgrims resort every year. These places are : Parasnath, near Calcutta, Mount Abu, the sanitarium of Rajputana, Chan- dragiri, in the Himalayas, Girnar, in Gujerath, and Satranjya in KathiawSr, the last being the most popular among them. The prin- cipal festivals of the Jains occur in the month of Bhadrapad, during which most of them fast and devote their time to reading reli- gious books in temples. The days of the birth and the death of the last two Ththankftrs are celebrated with great pomp.

Internal Structure

Although the sect had for its aim the abolition of the caste system, the Brahmanical influence has prevailed and the Jains are now broken up into numerous sub-castes, some of which are territorial and others occupational divisions. The follow- ing sub-divisions are met with in these Dominions : —

(1) Oswal. (10) Gujar.

(2) Agarwal. (11) Kambhoja.

(3) Porwal. (12) Bogar.

(4) Jaiswal. (13) Panchama.

(5) Srimali. (14) Chaturtha.

(6) Khandelwad. (15) Harad.

(7) Swahitwal. (16) Shri Srimali.

(8) Lad. (17) Shrawagi.

(9) Neve or Newad. Of these, the first ten appear to have come from the north and the rest from Southern India. They are all endogamous. Each of these divisions is further split up into eighty-four exogamous sections of the eponymous type, a list of which is appended to this article. These endogamous groups differ so widely from one another in their physical appearance, manner and usages, that a separate description of each in detail is necessary.

Oswals — are tall, handsome men and derive their name from an ancient village called Osian, the ruins of which are to be seen in the neighbourhood of Jodhpur. They are almost all Shwaitambar Jains, and were converted to the Jain faith by Jinadattasuri, the forty- fourth teacher from Mhavira. A legend, however, says that a Jain priest, named Ratna Prabhu Suri, visited the village (Osian) and begged for alms, but was given nothing. Raja Oppal Deva was reigning there and the enraged Yati caused the death of the Raja's son by snake-bite. On the pacification of the saint, the boy was restored to life, but the king had to give consent to the conversion of the whole village to the Jain faith. This event is said to have taken place on the 8th of the light half of Sravana Samvat 282.

Agarwals — a few have embraced Jainism and are not bigoted, for they intermarry freely with the Vaishnava Agarwals, the offspring being regarded as belonging to the religion of the father.

Porwals — are said to have embraced Jainism some seven hun- dred years ago. There are very few found in these Dominions.

ShraWagis — derive their name from the term ' Shrawak, or follower of the Jain religion, and trace their origin to Nemi Nath, a Yadu Bansi Raja of Dwarka. They are very strict in their reli- gious observances and carry the reverence for animal life to a ludicrous extent. They do not employ Brahmans for religious or ceremonial observances. They are Digambaras, do not eat food after sunset and light no lamp at night, because of the great regard they enter- tain for animal life. They are regarded as superior in rank to the Porwals.

Srimalis — are immigrants from Gujerath, where they were first converted to Jainism. They intermarry with the Oswals and do not differ from them in their religious views. Shri, Srimalis, Khandelwads, and Jaiswals — are found in very small numbers in the State.

All these classes have been fully described in the report on the Marwadi Banias. They are the bankers, traders, shop-keepers and money-lenders in the towns and villages of the Dominions and form the v^fealthiest portion of the community.

Swahitwah — are chiefly found in the Maratha Districts and have the appearance of Maratha Kunbis, from whom they were pro- bably originally recruited. They profess to belong to the Digamber sect of Jains and are strict in their religious observances. They are divided into two sub-castes (1) Swahitwal and (2) Setwal, based upon the jiifference of occupation. The latter weave bodice cloths and are cloth merchants, shop-keepers and money-lenders. The former are tailors. Unlike the orthodox Jains, they regulate their marriages, not by their traditionary eighty-four gotras, but by family surnames of the Maratha type. The surnames are : —

Lavhande.

Degaonker.

Swahitkar.

Burse.

Gajare.

Annadate.

Sonatakle.

Maisker.

Hudekar.

Wakale.

Ghante.

Ukhalker.

Baratker.

Kursale.

Bondare.

Pahinker.

Ghodke.

Chakote.

June.

Sangawar.

Bhagwati.

Kalyanker.

Ambekar.

Belavker.

Mallavker.

Panchwadker.

Satalker.

Alande.

Jogi.

Bhunde.

Kalak.

Dolas.

Intermarriages within the same section are avoided. A man may marry the daughter of his maternal uncle, paternal aunt or elder sister.

The Swahitwals marry their daughters as infants, and observe the standard marriage ceremony in vogue among the higher Maratha castes. The preliminary negotiations are conducted by the parents of the couple and, after they have been satisfactorily arranged, an auspicious day is fixed for the celebration of the wedding. A formal visit is paid by the bridegroom's people for the purpose of seemg the bride, and presenting her with clothes and jewels by way of betrothal or confirmation of the match. The bride's people also visit and inspect the bridegroom and present him with a turban. Marriage booths are erected at both houses and the bride and bridegroom, in their respective houses, are smeared with turmeric paste and oil, the bride after the bridegroom, the bride also receiving a part of the paste prepared for the bridegroom. DeOa Pratishtha (tJie installa- tion of the deity presiding over weddings) is performed at the temple of Parasnath, or Mahavir, when two brass jars, representing Parmeshti (the wedding deity), are placed before the jina, silk bracelets are tied on the wrists of the assembled guests, and round spots of sandal paste are made on their foreheads. On the distribution of pan- supari, the assembly breaks up. Next morning, the ceasecrated brass pots are taken in procession to the house and deposited before the family god,. On the wedding morn, the bridegroom starts in pro- cession on a bullock or a horse to the bride's house and halts, on the way, at Maruti's temple, where he is ceremonially accorded a fitting welcome by the bride's party, with presents of the nuptial dress. On arrival at the bride's door, the bride's father waters his mount and the bride s mother bedaubs his forehead with k.urikum (red powder) and offers him milk. Under the wedding pandai, the bridegroom stands facing the east, the bride being opposite to him, clothed in gay attire and decked in jewels which have been presented to her by the bridegroom. A silk cloth is interposed between them, auspicious stanzas are chanted by the priest, and at the end of each stanza turmeric-coloured rice is sprinkled by the assembly over the heads of the bridal couple. The curtain is removed, the couple are seated on the seats upon which they were formerly standing, and a fine cotton thread is wound around them thirteen times. The Kanyadan ceremony is next performed, two bracelets made of the encircling thread being fastened one on the bride's wrist and the other on that of the bridegroom. Their garments are knotted to- gether, the- bridegroom wears the sacred thread and manguhutra is tied around the bride's neck. These rites, from Antarpat to the wearing of manguhutra by the bride, form the essential portion of the ceremony. The ceremony concludes with a feast given to relatives and friends. Widows are allowed to marry and divorce is recognised. Both widows and divorced wives marry by inferior rites, in which the garments of the bridal couple are knotted together and a feast is furnished to the relatives. Polygamy is permitted and a man may have as many wives as "he can afford to maintain. A woman taken in adultery is expelled from the caste. In addition to the Ththankars, the Swahitwals worship the tutelary deity Padmakshi, whose temple is said to be* situated at Warangal. The Hindu gods are accorded due reverence. Brahmans are employed for religious and ceremonial observances. The Swahitwals burn their adult dead, the ashes being collected on the third day after death and thrown into a sacred stream. In pursuance of Jain injunctions, they do not perform the Sradha ceremony, but, contrary to them, they observe mourning for ten days. Their social position is high and all castes, from the Maratha Kunbis downwards, eat k^chi from their hands. They are vege- tarians and abstain from radishes, onions, garlic, assafoetida, clarified butter and liquor, in addition to flesh.

Bogar — the Bhopal Jain Kasars, bangle dealers and braziers, claim to have originally been Kshatriyas, but were doomed by their patron goddess Kalika to the low occupation of a k^sar (brazier). They are to be found in small numbers in the Carnatic and Maratha- wada Districts. They have five endogamous divisions: (1) Chaturtha Bogar, (2) Pancham Bogar, (3) Pancham Jain, (4) Harad and (5) Apastamb Harad, the members of which are said to interdine but not to intermarry. They profess to follow the standard exogamous system of the Jains given in the list at the conclusion of this article. But this seems to be nominal, and marriages are actually governed by exogamous sections, mostly of the territorial type. Those pre- valent among the Maratha Bogars are —

Halge. Vibhute.

Chilwant. Dahibhate.

Kathole. Kolape

Deware.

Warade.

Bede.

Dahatonde.

Helasker.

Aher.

Mene.

Husang.

Bhandare

Anuker.

Katie.

Bhujabale.

Satpute.

Chingare.

Vannere.

Mangulker.

Ghase.

Dabhe.

Kemker.

Adamane.

Tambat.

Pede.

Lokhande.

Bedare.

Some of these section names, such as Bhujabale, Dahibhate, Dahatonde and Admane, are titular in character. A man is prohi- bited from marrying outside the sub-caste, or inside the section, to which he belongs. He may marry the daughters of his maternal uncle, paternal aunt or elder sister. He may also marry two sisters.

Infant marriage is practised by the caste, the girls being married between the ages of two and twelve years. Polygamy is allowed, but is not practised on a large scale.

The Bogar marriage does not differ materially from that in vogue among the local Brahmans, Saptapadi, or seven circuits around the sacrificial fire, being deemed the binding portion of the ceremony. Widows are allowed to marry again, and divorce is permitted on the ground of the wife's unchastity, barrenness or ill- temper. Divorced wives re-marry by the same rites as widows.

The Bogars are Digambar Jains and confine their devotion to Parasnath, one of the Tirthanl^ars. Their favourite object of worship is Kalikadevi, called also Padmakshi, honoured on the fifteenth of Falgun (February) and on the third of the light of Asadha with offerings of sweetmeats and flowers. The gods of the Hindu pan- theon are also duly honoured. Brahmans are engaged at the marriage ceremony.

The dead are burned in a lying posture on a funeral fire made generally of cowdung cakes. Children dying prior to teething are buried. ,The ashes are collected on the third day after death and thrown into a pond or a river. Mourning is observed for ten days, and on the tenth day after death balls of flour or rice are offered for the benefit of the dead. On the twelfth and thirteenth days after death, the Sradha ceremony is performed and caste people are fed In this last rite the Bogars diverge from the general tenets of Jainism. The Bogars are vegetarians and rank socially below the Brahmans and above the agricultural castes of the locality. Previous to the marriage ceremony, the male members of the caste are invested with the sacred thread. Social disputes are referred for decision to a caste council, headed by a chief called mehetarya. There is a saying in <• Marathi regarding the origin of the caste — ' ' Panch Panchal Ani Sahawa Bhopal " which means that the goddess Kalika first created five Panchals, viz., Sonar, Lobar, Sutar, Tambatker and Silpi ; and then she created the sixth, the Bhopal caste.

Kambhoja — are chiefly to be found in Telingana, extending as far north as Benares and Nagpur. Traditions say that they came originally from Kambhoja Desh (the country of Kambhoja) which was sitifated in Southern India, but cannot be identified at the present day. The almost Dravidian features of the Kambhoja give support to their southern origin. These people were probably converted to the faith between the ninth and twelfth centuries, during which Jainism flourished in Southern India in its full vigour, having been introduced first in Malabar, by the king Amogha Varsha, early in the ninth century, and subsequently patronised by the princes of Conjevaram, Madura and Mysore. The Kambhojas are Jains of the Digambar sect, and strictly adhere to the doctrines and tenets of their religion.

As far as any information goes, the Kambhojas have no endogam- ous divisions. Their exogamous system is of the eponymous type, being based upon the eighty-four gotras into which all the Jains of India have been theoretically broken up. But the Kambhojas of Hingoli allege that their marriages are regulated by exogamous sections, which are a mixture of territorial, eponymous and titular names. Some of these are noticed below : —

Mukerwar. Somashet.

Kandi. Todal.

Kariwal. Arpal.

Waral . Tyaral .

Yambal. Madrap.

Mahajan. Mashta.

Yarmal. Marriages within the same section are avoided. Daughters of maternal uncles, paternal aunts and elder sisters may be married. Two sisters may be married to the same man.

Infant marriage is practised by the caste, the girl's age being between two and twelve years. A bride-price, which sometimes amounts to Rs. 400, is paid to the girl's parents.

After the bride has been selected, the parents of the bridegroom go to her house to see her and present her with clothes and jewels. The girl's parents also visit the bridegroom and make him presents. The marriage ceremony takes place in a wedding pandal, erected in front of the bride's house, and made of nine pillars representing the nine planets. The marriage shows very little divergence from the orthodox usage current among the higher castes of Hindus of the locality. Previous to the wedding, Padmawati, their tutelary goddess, and Parasnath, are invoked. Immediately after the Antarpat ritual, the bride and the bridegroom stand face to face, the bridegroom holding a pusti (mangalsutra) in his hand and the bride the sacred thread ; these they exchange after the priest has recited appropriate mantras. This rite is supposed to constitute the binding portion of the ceremony. On the 7th day after the wedding, the Naghali ceremony is performed, when 84 heaps of rice, repre- senting the 84 traditionary goiras of the sect, are arranged in a square in which the bride and bridegroom are made to sit by the officiating priest and to pronounce all the gob as.

Widows are not allowed to marry again, nor is divorce recognised. Polygamy is permitted, there being no limit to the number of wives a man may have.

A girl, on attaining puberty, is unclean for eleven days. During this time she is smeared daily with scented unguents, bathed in warm water and given nourishing food. On the eleventh day, she has to undergo purificatory rites. The Pvnyawachana ceremony is performed, ' after which the girl steps over a line of live coals and becomes ceremonially pure.

A woman after child birth is impure for twenty-one days. On the fifth day after birth, five pebbles are placed on the rim of the pit in which the umbilical cord was buried and around the pebbles are grouped, in heaps, cotton seeds, unhusked rice, wheat, millet and udid (a variety of kidney bean — Phaseolus Mungo). After these have been worshipped,, the midwife fills a pot with them, dances and sings a song, the refrain of which is, " May your baby live long and jump like a frog." On the twenty-first day after birth, the mother ^^oes out, worships the rim of a well, round which she walks three times, and returns home with a pot filled with water. On her return the child is placed in a cradle and named.

The Kambhojas are orthodox Jains, carefully observing all the rites of the sect, and worshipping the twenty-four Tirthankars, four- teen Ashtakas and fourteen Jalmals. A grand festival is held in honour of the divinities from the 4th to the 14th of the light half of Bhadrapad (September). They make pilgrimages to Samet Shikhara, situated near Calcutta. Bhattdrakas, or Jain priests, are engaged tot religious and ceremonial observances.

The dead are burned in a lying posture, with the head pointing to the south. The ashes ate collected on the third day after death and thrown into a sacred river. Moutning is observed fot thitteen days. No Sradha is petformed in honour of the deceased.

The Kambhojas are vegetarians and abstain fiom flesh and feimented drink. As they are believed to be outside the pale of the Hindu caste, their social status cannot be determined. They do not eat at night, nor do they kindle a light for fear that moths may be attracted by the flame and perish. They do not eat kachi from the hands of any Hindu caste. They ate shop-keepers, cloth merchants, and retail dealers.

Newad Jains— have a tradition that they came from Mewad into these Dominions. They call themselves Sawaji and have the title ' Sa ' attached to their names.

The Newads have no endogamous divisions, but their exogamous sections are numerous. A few of these ate

Dagoja. Dolchipure, ,

Phulade. Chandre.

Ikshwak. Khapre.

Rawul. Kare.

Gore.

Marriages are avoided within the same section. With regard to the prohibited relationship, which supplements the rule of exogamy, they are guided by the same laws as the other local castes.

A Newad girl is married as an infant, and a bride-price of Rs. 1 ,000 is paid to her parents. This enormous increase in the bride-price is due partly to the paucity of girls among th«Tn and partly to the fact that they are debarred from intermarriages with the parent stock, from which they have long been isolated. The ceremony takes place at the bridegroom's house and extends over ten days. On the first day, Parasnath, Saraswati and other household gods are invoked to protect the couple from harm or evil during the ceremony. Offerings of wheaten cakes and milk are made to the deities and the caste people of the neighbourhood are feasted in their honour. The bride's party, on their arrival at the bridegroom's village, are accom- modated at the latter's house. After all the ceremonies previous to the wedding, such as Deca\arya, Haldi and Airani Kundalu, have been performed and all preliminary arrangements have been com- pleted, the bridegroom, dressed in yellow, with a red turban on his head, is paraded on horseback through the streets. On arrival at the entrance door of his house, the door is shut, the bridegroom s party standing outside and the bride's party standing inside the house. Then follows a curious dialogue between them. The bride makes enquiries regarding the bridegroom's whereabouts, his religion and his ways of living, to which the bridegroom responds. Q, — What is your religion? What saints do you adore? Who is

your guru'^ What religious book guides you? How many times a day do you offer prayers ? Upon whom do you bestow your affections?

A. — Sandhata is my religion, and 1 honour Arhanta (saints).

Nighranta is my gum, and i have studied a million reli- gious books. I offer prayers to God three times a day, and the whole world is the object of my love.

Q. — Lord of men ! will you please give me information regarding

your parents, your country and your ways of living ?

A. — Beautiful damsel ! Hindusthana is my home and Sa is my

name. Mounted on a noble charger and armed with a sword

I roam like a Kshatriya warrior of the Moda clan. O ! maiden of charming teeth and the graceful form of the swan, adorn yourself in your choicest jewels, wear around your neck a garland of pearls drawn from the head of an elephant, and be prepared for the wedding.

The dialogue ends and the door opens. The bridegroom is conducted to the wedding booth, and is made to stand before the bride. After he has been invested with the sacred thread, antarpat is held between them, and the pair are wedded by the Jain priest reciting benedictory mantras. The Kankan-bandhan and Kanydddn ceremonies follow, after which the bridegroom ties the mangakutra (a string of black beads) round the bride's neck. This last ritiual forms the binding portion of the ceremony, after which the marriage becomes irrevocable.

The Newads are Jains of the Digambar sect, Parasnath and Padmavati are their favourite objects of worship, to whom, every Friday, they offer wheaten cakes and milk, which the devotees subsequently consume.

A girl, on attaining puberty, is said to be ceremonially impure for sixteen days. On the 16th day, the Garbhadan ceremony (puri- fication of the womb) is performed, and the girl is allowed to cohabit with her husband.

All Jains have a firm belief in magic and charms, and they pacify evil spirits, ghosts and witches, in the same way as other Hindu castes do.

The dead are burnt in a lying posture, with the head pointing to the south. The corpse is washed, dressed in dry clothes, and borne to the cremation ground on a bier of galer wood (Ficus glomerata), the bearers uttering the word 'Arhan,' all the way. The dead body is placed on a funeral pyre of cowdung cakes and the chief mourner. walking three times round it, sets fire to the pile. The ashes are collected on the third day after death and thrown into the nearest river or lank. No Sradha is celebrated, but the adult dead are mourned for 10 days, if they are agnates, and for three days if cognates.

The Maratha Kunbis and the lower classes eat k.achi from the hands of the members of this caste ; they may, therefore, be ranked above the Kunbis, and below the Brahmans, but, being outside the pale of Brahmanism, as stated above, their rank in the Hindu social system cannot be definitely stated. They abstain from flesh, wine, garlic and onions. In matters of food they observe all the restrictions imposed upon Jains in general. •:

The Newads are generally rich traders and deal chiefly in silver and gold.

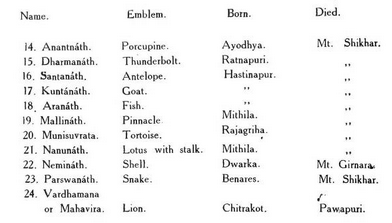

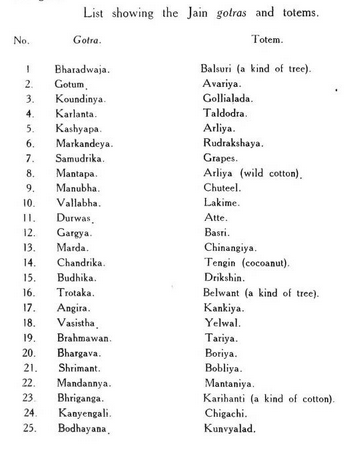

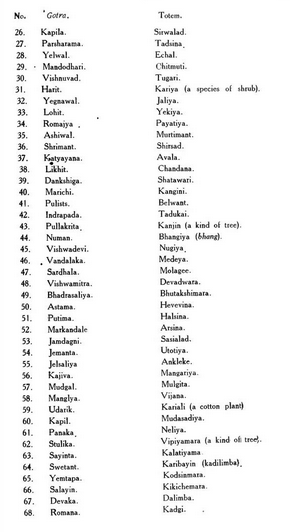

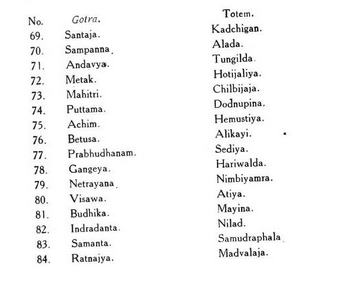

List showing the Jain gotras and totems.