Jain: South India

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Contents |

Jain

Few,” Mr. T. A. Gopinatha Rao writes, “even among educated persons, are aware of the existence of Jainas and Jaina centres in Southern India. The Madras Presidency discloses vestiges of Jaina dominion almost everywhere, and on many a roadside a stone Tīrthankara, standing or sitting cross-legged, is a common enough sight. The present day interpretations of these images are the same all over the Presidency. If the images are two, one represents a debtor and the other a creditor, both having met on the road, and waiting to get their accounts settled and cleared. If it is only one image, it represents a debtor paying penalty for not having squared up his accounts with his creditor.” It is recorded, in the Madras Census Report, 1891, that “out of a total of 25,716 Jains, as many as 22,273 have returned both caste and sub-division as Jain. The remainder have returned 22 sub-divisions, of which some, such as Digambara and Swetambara, are sectarian rather than caste divisions, but others like Marvādi, Osval, Vellālan, etc., are distinct castes. And the returns also show that some Jains have returned well-known castes as their main castes, for we have Jain Brāhmans, Kshatriyas, Gaudas, Vellālas, etc. The Jain Bants, however, have all returned Jain as their main caste.” At the Madras census, 1901, 27,431 Jains were returned. Though they are found in nearly every district of the Madras Presidency, they occur in the largest number in the following:—

South Canara 9,582

North Arcot 8,128

South Arcot 5,896

At the Mysore census, 1901, 13,578 Jains were returned. It is recorded in the report that “the Digambaras and Swetambaras are the two main divisions of the Jain faith. The root of the word Digambara means space clad or sky clad, i.e., nude, while Swetambara means clad in white. The Swetambaras are found more in Northern India, and are represented but by a small number in Mysore. The Digambaras are said to live absolutely separated from society, and from all worldly ties. These are generally engaged in trade, selling mostly brass and copper vessels, and are scattered all over the country, the largest number of them being found in Shimoga, Mysore, and Hassan districts. Srāvana Belagola, in the Hassan district, is a chief seat of the Jains of the province.

Tīrthankaras are the priests of the Jain religion, and are also known as Pitambaras. The Jain Yatis or clergy here belong to the Digambara sect, and cover themselves with a yellow robe, and hence the name Pithambara.” The Dāsa Banajigas of Mysore style themselves Jaina Kshatriya Rāmānujas.

In connection with the terms Digambara and Swetambara, it is noted by Bühler that “Digambara, that is those whose robe is the atmosphere, owe their name to the circumstance that they regard absolute nudity as the indispensable sign of holiness, though the advance of civilization has compelled them to depart from the practice of their theory. The Swetambara, that is they who are clothed in white, do not claim this doctrine, but hold it as possible that the holy ones who clothe themselves may also attain the highest goal. They allow, however, that the founder of the Jaina religion and his first disciples disdained to wear clothes.”

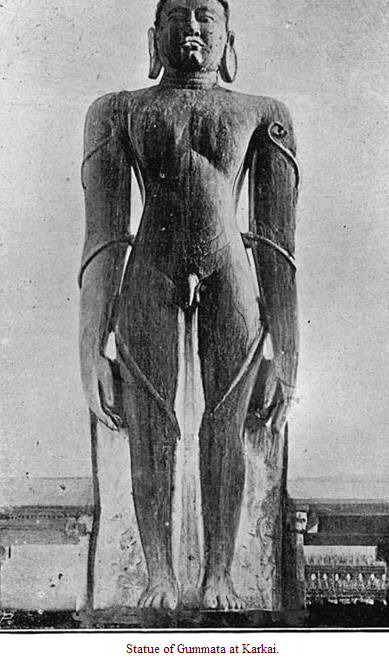

The most important Jain settlement in Southern India at the present day is at Srāvana Belagola in Mysore, where the Jains are employed in the manufacture of metal vessels for domestic use. The town is situated at the base of two hills, on the summit of one of which, the Indra Betta, is the colossal statue of Gomatēsvara, Gummatta, or Gomata Rāya,3 concerning which Mr. L. Rice writes as follows. “The image is nude, and stands erect, facing the north. The figure has no support above the thighs. Up to that point it is represented as surrounded by ant-hills, from which emerge serpents. A climbing plant twines itself round both legs and both arms, terminating at the upper part of the arm in a cluster of fruit or berries. The pedestal on which the feet stand is carved to represent an open lotus. The hair is in spiral ringlets, flat to the head, as usual in Jain images, and the lobe of the ears lengthened down with a large rectangular hole. The extreme height of the figure may be stated at 57 feet, though higher estimates have been given—60 feet 3 inches by Sir Arthur Wellesley (afterwards Duke of Wellington), and 70 feet 3 inches by Buchanan.” Of this figure, Fergusson writes5 that nothing grander or more imposing exists anywhere out of Egypt, and even there no known statue surpasses it in height, though, it must be confessed, they do excel it in the perfection of art they exhibit.”

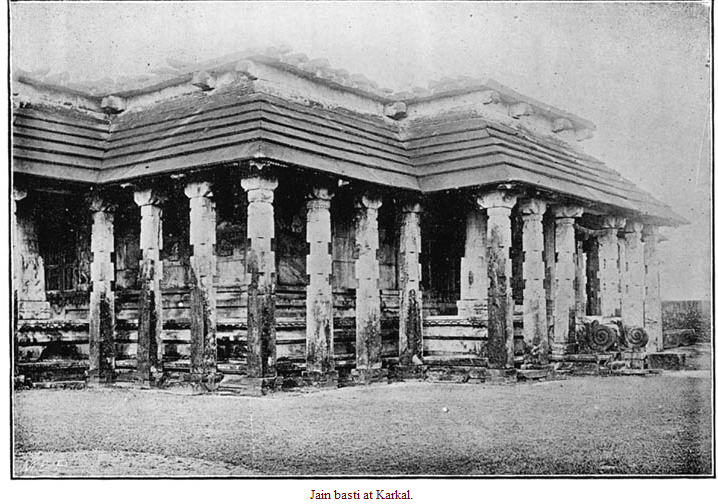

Other colossal statues of Gummata are situated on the summit of hills outside the towns of Karkal and Vēnūr or Yēnūr in South Canara. Concerning the former, Dr. E. Hultzsch writes as follows. “It is a monolith consisting of the figure itself, of a slab against which it leans, and which reaches up to the wrists, and of a round pedestal which is sunk into a thousand-petalled lotus flower. The legs and arms of the figure are entwined with vines (drâkshâ). On both sides of the feet, a number of snakes are cut out of the slab against which the image leans. Two inscriptions on the sides of the same slab state that this image of Bāhubalin or Gummata Jinapati was set up by a chief named Vîra-Pândya, the son of Bhairava, in A.D. 1431–32. An inscription of the same chief is engraved on a graceful stone pillar in front of the outer gateway. This pillar bears a seated figure of Brahmadêva, a chief of Pattipombuchcha, the modern Humcha in Mysore, who, like Vîra-Pândya, belonged to the family of Jinadatta, built the Chaturmukha basti in A.D. 1586–87.

As its name (chaturmukha, the four-faced) implies, this temple has four doors, each of which opens on three black stone figures of the three Tīrthankaras Ari, Malli, and Munisuvrata. Each of the figures has a golden aureole over the head.” According to a legend recorded by Mr. M. J. Walhouse, the Karkal statue, when finished, was raised on to a train of twenty iron carts furnished with steel wheels, on each of which ten thousand propitiatory cocoanuts were broken and covered with an infinity of cotton. It was then drawn by legions of worshippers up an inclined plane to the platform on the hill-top where it now stands.

The legend of Kalkuda, who is said to have made the colossal statue at “Belgula,” is narrated at length by Mr. A. C. Burnell. Told briefly, the story is as follows. Kalkuda made a Gummata two cubits higher than at Bēlūr. Bairanasuda, King of Karkal, sent for him to work in his kingdom. He made the Gummatasāmi. Although five thousand people were collected together, they were not able to raise the statue. Kalkuda put his left hand under it, and raised it, and set it upright on a base. He then said to the king “Give me my pay, and the present that you have to give to me. It is twelve years since I left my house, and came here.” But the king said “I will not let Kalkuda, who has worked in my kingdom, work in another country,” and cut off his left hand and right leg. Kalkuda then went to Timmanājila, king of Yēnūr, and made a Gummata two cubits higher than that at Karkal.

In connection with the figure at Srāvana Belagola, Fergusson suggests that the hill had a mass or tor standing on its summit, which the Jains fashioned into a statue.

The high priest of the Jain basti at Karkal in 1907 gave as his name Lalitha Kirthi Bhattaraka Pattacharya Variya Jiyaswāmigalu. His full-dress consisted of a red and gold-embroidered Benares body-cloth, red and gold turban, and, as a badge of office, a brush of peacock’s feathers mounted in a gold handle, carried in his hand. On ordinary occasions, he carried a similar brush mounted in a silver handle. The abhishēkam ceremony is performed at Karkal at intervals of many years. A scaffold is erected, and over the colossal statue are poured water, milk, flowers, cocoanuts, sugar, jaggery, sugar-candy, gold and silver flowers, fried rice, beans, gram, sandal paste, nine kinds of precious stones, etc.

Concerning the statue at Yēnūr, Mr. Walhouse writes that “it is lower than the Kârkala statue (41½ feet), apparently by three or four feet. It resembles its brother colossi in all essential particulars, but has the special peculiarity of the cheeks being dimpled with a deep grave smile. The salient characteristics of all these colossi are the broad square shoulders, and the thickness and remarkable length of the arms, the tips of the fingers, like Rob Roy’s, nearly reaching the knees. [One of Sir Thomas Munro’s good qualities was that, like Rāma, his arms reached to his knees or, in other words, he possessed the quality of an Ājanubāhu, which is the heritage of kings, or those who have blue blood in them.] Like the others, this statue has the lotus enwreathing the legs and arms, or, as Dr. Burnell suggests, it may be jungle creepers, typical of wrapt meditation. [There is a legend that Bāhubalin was so absorbed in meditation in a forest that climbing plants grew over him.] A triple-headed cobra rises up under each hand, and there are others lower down.”

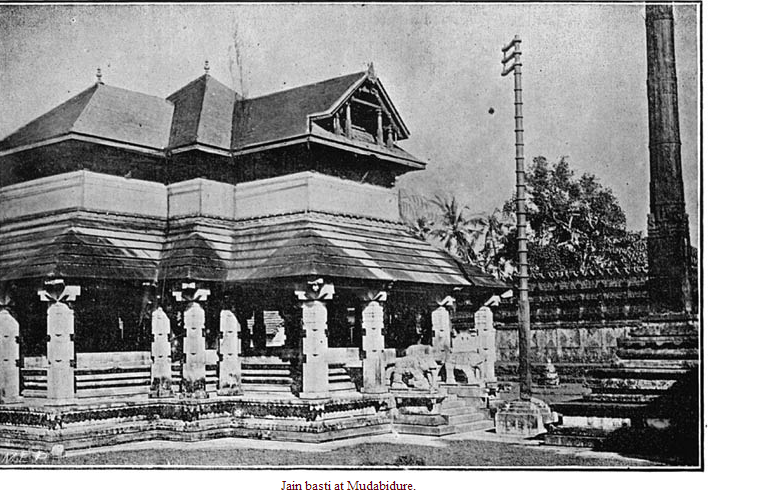

“The village of Mūdabidure in the South Canara district,” Dr. Hultzsch writes, “is the seat of a Jaina high priest, who bears the title Chârukirti-Panditâchârya-Svâmin. He resides in a matha, which is known to contain a large library of Jaina manuscripts. There are no less than sixteen Jaina temples (basti) at Mûdabidure. Several of them are elaborate buildings with massive stone roofs, and are surrounded by laterite enclosures. A special feature of this style of architecture is a lofty monolithic column called mânastambha, which is set up in front of seven of the bastis. In two of them a flagstaff (dhvajastambha), which consists of wood covered with copper, is placed between the mânastambha and the shrine. Six of them are called Settarabasti, and accordingly must have been built by Jaina merchants (Setti).

The sixteen bastis are dedicated to the following Tîrthankaras:—Chandranatha or Chandraprabha, Nêminâtha, Pârsvanâtha, Âdinâtha, Mallinâtha, Padmaprabha, Anantanâtha, Vardhamâna, and Sântinâtha. In two of these bastis are separate shrines dedicated to all the Tîrthankaras, and in another basti the shrines of two Yakshīs. The largest and finest is the Hosabasti, i.e., the new temple, which is dedicated to Chandranâtha, and was built in A.D. 1429–30. It possesses a double enclosure, a very high mânastambha, and a sculptured gateway. The uppermost storey of the temple consists of wood-work. The temple is composed of the shrine (garbagriha), and three rooms in front of it, viz., the Tîrthakaramandapa, the Gaddigemandapa, and the Chitramandapa. In front of the last-mentioned mandapa is a separate building called Bhairâdêvimandapa, which was built in A.D. 1451–52. Round its base runs a band of sculptures, among which the figure of a giraffe deserves to be noted.

The idol in the dark innermost shrine is said to consist of five metals (pancha-lôha), among which silver predominates. The basti next in importance is the Gurugalabasti, where two ancient talipot (srîtâlam) copies of the Jaina Siddhânta are preserved in a box with three locks, the keys of which are in charge of three different persons. The minor bastis contain three rooms, viz., the Garbhagriha, the Tîrthakaramandapa, and the Namaskâramandapa. One of the sights of Mûdabidire is the ruined palace of the Chautar, a local chief who follows the Jaina creed, and is in receipt of a pension from the Government. The principal objects of interest at the palace are a few nicely-carved wooden pillars. Two of them bear representations of the pancha-nârîturaga, i.e., the horse composed of five women, and the nava-nârî-kunjara, i.e., the elephant composed of nine women. These are fantastic animals, which are formed by the bodies of a number of shepherdesses for the amusement of their Lord Krishna.

The Jains are divided into two classes, viz., priests (indra) and laymen (srivaka). The former consider themselves as Brâhmanas by caste. All the Jainas wear the sacred thread. The priests dine with the laymen, but do not intermarry with them. The former practice the makkalasantâna, i.e., the inheritance through sons, and the latter aliya-santâna, i.e., the inheritance through nephews. The Jainas are careful to avoid pollution from contact with outcastes, who have to get out of their way in the road, as I noticed myself. A Jaina marriage procession, which I saw passing, was accompanied by Hindu dancing-girls. Near the western end of the street in which most of the Jainas live, a curious spectacle presents itself. From a number of high trees, thousands of flying foxes (fruit-bat, Pteropus medius) are suspended. They have evidently selected the spot as a residence, because they are aware that the Jainas, in pursuance of one of the chief tenets of their religion, do not harm any animals. Following the same street further west, the Jaina burial-ground is approached. It contains a large ruined tank with laterite steps, and a number of tombs of wealthy Jain merchants. These tombs are pyramidal structures of several storeys, and are surmounted by a water-pot (kalasa) of stone. Four of the tombs bear short epitaphs. The Jainas cremate their dead, placing the corpse on a stone in order to avoid taking the life of any stray insect during the process.”

In their ceremonials, e.g., marriage rites, the Jains of South Canara closely follow the Bants. They are worshippers of bhūthas (devils), and, in some houses, a room called padōli is set apart, in which the bhūtha is kept. When they make vows, animals are not killed, but they offer metal images of fowls, goats, or pigs.

Of the Jains of the North Arcot district, Mr. H. A. Stuart writes that “more than half of them are found in the Wandiwash taluk, and the rest in Arcot and Pōlūr. Their existence in this neighbourhood is accounted for by the fact that a Jain dynasty reigned for many years in Conjeeveram. They must at one time have been very numerous, as their temples and sculptures are found in very many places, from which they themselves have now disappeared. They have most of the Brāhman ceremonies, and wear the sacred thread, but look down upon Brāhmans as degenerate followers of an originally pure faith. For this reason they object generally to accepting ghee (clarified butter) or jaggery (crude sugar), etc., from any but those of their own caste. They are defiled by entering a Pariah village, and have to purify themselves by bathing and assuming a new thread. The usual caste affix is Nainar, but a few, generally strangers from other districts, are called Rao, Chetti, Dās, or Mudaliyar.

At Pillapālaiyam, a suburb of Conjeeveram in the Chingleput district, is a Jain temple of considerable artistic beauty. It is noted by Sir M. E. Grant Duff that this is “left unfinished, as it would seem, by the original builders, and adapted later to the Shivite worship. Now it is abandoned by all its worshippers, but on its front stands the census number 9–A—emblematic of the new order of things.”

Concerning the Jains of the South Arcot district, Mr. W. Francis writes that “there is no doubt that in ancient days the Jain faith was powerful in this district. The Periya Purānam says that there was once a Jain monastery and college at Pātaliputra, the old name for the modern Tirupāpuliyūr, and remains of Jain images and sculptures are comparatively common in the district. The influence of the religion doubtless waned in consequence of the great Saivite revival, which took place in the early centuries of the present era, and the Periya Purānam gives a story in connection therewith, which is of local interest. It says that the Saivite poet-saint Appar was at one time a student in the Jain college at Pātaliputra, but was converted to Saivism in consequence of the prayers of his sister, who was a devotee of the deity in the temple at Tiruvādi near Panruti.

The local king was a Jain, and was at first enraged with Appar for his fervent support of his new faith. But eventually he was himself induced by Appar to become a Saivite, and he then turned the Pāliputra monastery into a temple to Siva, and ordered the extirpation of all Jains. Later on there was a Jain revival, but this in its turn was followed by another persecution of the adherents of that faith. The following story connected with this latter occurs in one of the Mackenzie Manuscripts, and is supported by existing tradition. In 1478 A.D., the ruler of Gingee was one Venkatāmpēttaī, Venkatapati, who belonged to the comparatively low caste of the Kavarais. He asked the local Brāhmans to give him one of their daughters to wife. They said that, if the Jains would do so, they would follow suit. Venkatapati told the Jains of this answer, and asked for one of their girls as a bride.

They took counsel among themselves how they might avoid the disgrace of connecting themselves by marriage with a man of such a caste, and at last pretended to agree to the king’s proposal, and said that the daughter of a certain prominent Jain would be given him. On the day fixed for the marriage, Venkatapati went in state to the girl’s house for the ceremony, but found it deserted and empty, except for a bitch tied to one of the posts of the verandah. Furious at the insult, he issued orders to behead all Jains. Some of the faith were accordingly decapitated, others fled, others again were forced to practice their rites secretly, and yet others became Saivites to escape death. Not long afterwards, some of the king’s officers saw a Jain named Vīrasēnāchārya performing the rites peculiar to his faith in a well in Vēlūr near Tindivanam, and hauled him before their master. The latter, however, had just had a child born to him, was in a good temper, and let the accused go free; and Vīrasēnāchārya, sobered by his narrow escape from death, resolved to become an ascetic, went to Srāvana Belgola, and there studied the holy books of the Jain religion. Meanwhile another Jain of the Gingee country, Gāngayya Udaiyār of Tāyanūr in the Tindivanam taluk, had fled to the protection of the Zamindar of Udaiyārpālaiyam in Trichinopoly, who befriended him and gave him some land.

Thus assured of protection, he went to Srāvana Belgola, fetched back Vīrasēnāchārya, and with him made a tour through the Gingee country, to call upon the Jains who remained there to return to their ancient faith. These people had mostly become Saivites, taken off their sacred threads and put holy ashes on their foreheads, and the name Nīrpūsi Vellālas, or the Vellālas who put on holy ash, is still retained. The mission was successful, and Jainism revived. Vīrasēnāchārya eventually died at Vēlūr, and there, it is said, is kept in a temple a metal image of Parsvanātha, one of the twenty-four Tīrthankaras, which he brought from Srāvana Belgola. The descendants of Gāngayya Udaiyār still live in Tāyanūr, and, in memory of the services of their ancestor to the Jain cause, they are given the first betel and leaf on festive occasions, and have a leading voice in the election of the high-priest at Sittāmūr in the Tindivanam taluk. This high-priest, who is called Mahādhipati, is elected by representatives from the chief Jain villages.

These are, in Tindivanam taluk, Sittāmūr itself, Vīranāmūr, Vilukkam, Peramāndūr, Alagrāmam, and the Vēlūr and Tāyanūr already mentioned. The high-priest has supreme authority over all Jains south of Madras, but not over those in Mysore or South Canara, with whom the South Arcot community have no relations. He travels round in a palanquin with a suite of followers to the chief centres—his expenses being paid by the communities he visits—settles caste disputes, and fines, and excommunicates the erring. His control over his people is still very real, and is in strong contrast to the waning authority of many of the Hindu gurus. The Jain community now holds a high position in Tindivanam taluk, and includes wealthy traders and some of quite the most intelligent agriculturists there.

The men use the title of Nayinār or Udaiyār, but their relations in Kumbakōnam and elsewhere in that direction sometimes call themselves Chetti or Mudaliyār. The women are great hands at weaving mats from the leaves of the date-palm. The men, except that they wear the thread, and paint on their foreheads a sect-mark which is like the ordinary Vaishnavite mark, but square instead of semi-circular at the bottom, and having a dot instead of a red streak in the middle, in general appearance resemble Vellālas. They are usually clean shaved. The women dress like Vellālas, and wear the same kind of tāli (marriage emblem) and other jewellery.

The South Arcot Jains all belong to the Digambara sect, and the images in their temples of the twenty-four Tīrthankaras are accordingly without clothing. These temples, the chief of which are those at Tirunirankonrai and Sittāmūr, are not markedly different in external appearance from Hindu shrines, but within these are images of some of the Tīrthankaras, made of stone or of painted clay, instead of representations of the Hindu deities. The Jain rites of public worship much resemble those of the Brāhmans. There is the same bathing of the god with sacred oblations, sandal, and so on; the same lighting and waving of lamps, and burning of camphor; and the same breaking of cocoanuts, playing of music, and reciting of sacred verses. These ceremonies are performed by members of the Archaka or priest class. The daily private worship in the houses is done by the laymen themselves before a small image of one of the Tīrthankaras, and daily ceremonies resembling those of the Brāhmans, such as the pronouncing of the sacred mantram at daybreak, and the recital of forms of prayer thrice daily, are observed.

The Jains believe in the doctrine of re-births, and hold that the end of all is Nirvāna. They keep the Sivarātri and Dīpāvali feasts, but say that they do so, not for the reasons which lead Hindus to revere these dates, but because on them the first and the last of the twenty-four Tīrthankaras attained beatitude. Similarly they observe Pongal and the Ayudha pūja day. They adhere closely to the injunctions of their faith prohibiting the taking of life, and, to guard themselves from unwittingly infringing them, they do not eat or drink at night lest they might thereby destroy small insects which had got unseen into their food. For the same reason, they filter through a cloth all milk or water which they use, eat only curds, ghee and oil which they have made themselves with due precautions against the taking of insect life, or known to have been similarly made by other Jains, and even avoid the use of shell chunam (lime).

The Vēdakkārans (shikāri or hunting caste) trade on these scruples by catching small birds, bringing them to Jain houses, and demanding money to spare their lives. The Jains have four sub-divisions, namely, the ordinary laymen, and three priestly classes. Of the latter, the most numerous are the Archakas (or Vādyārs). They do the worship in the temples. An ordinary layman cannot become an Archaka; it is a class apart. An Archaka can, however, rise to the next higher of the priestly classes, and become what is called an Annam or Annuvriti, a kind of monk who is allowed to marry, but has to live according to certain special rules of conduct. These Annams can again rise to the highest of the three classes, and become Nirvānis or Munis, monks who lead a celibate life apart from the world. There is also a sisterhood of nuns, called Aryānganais, who are sometimes maidens, and sometimes women who have left their husbands, but must in either case take a vow of chastity. The monks shave their heads, and dress in red; the nuns similarly shave, but wear white. Both of them carry as marks of their condition a brass vessel and a bunch of peacock’s feathers, with which latter they sweep clean any place on which they sit down, lest any insect should be there. To both classes the other Jains make namaskāram (respectful salutation) when they meet them, and both are maintained at the cost of the rest of the community.

The laymen among the Jains will not intermarry, though they will dine with the Archakas, and these latter consequently have the greatest trouble in procuring brides for their sons, and often pay Rs. 200 or Rs. 300 to secure a suitable match. Otherwise there are no marriage sub-divisions among the community, all Jains south of Madras freely intermarrying. Marriage takes place either before or after puberty. Widows are not allowed to remarry, but are not required to shave their heads until they are middle-aged. The dead are burnt, and the death pollution lasts for twelve days, after which period purification is performed, and the parties must go to the temple. Jains will not eat with Hindus. Their domestic ceremonies, such as those of birth, marriage, death and so on resemble generally those of the Brāhmans. A curious difference is that, though the girls never wear the thread, they are taught the thread-wearing mantram, amid all the ceremonies usual in the case of boys, when they are about eight years old.”

It is recorded, in the report on Epigraphy, 1906–1907, that at Eyil in the South Arcot district the Jains asked the Collector for permission to use the stones of the Siva temple for repairing their own. The Collector called upon the Hindus to put the Siva temple in order within a year, on pain of its being treated as an escheat. Near the town of Madura is a large isolated mass of naked rock, which is known as Ānaimalai (elephant hill). “The Madura Sthala Purāna says it is a petrified elephant. The Jains of Conjeeveram, says this chronicle, tried to convert the Saivite people of Madura to the Jain faith. Finding the task difficult, they had recourse to magic. They dug a great pit ten miles long, performed a sacrifice thereon, and thus caused a huge elephant to arise from it. This beast they sent against Madura. It advanced towards the town, shaking the whole earth at every step, with the Jains marching close behind it. But the Pāndya king invoked the aid of Siva, and the god arose and slew the elephant with his arrow at the spot where it now lies petrified.”

In connection with the long barren rock near Madura called Nāgamalai (snake hill), “local legends declare that it is the remains of a huge serpent, brought into existence by the magic arts of the Jains, which was only prevented by the grace of Siva from devouring the fervently Saivite city it so nearly approaches.” Two miles south of Madura is a small hill of rock named Pasumalai. “The name means cow hill, and the legend in the Madura Sthala Purāna says that the Jains, being defeated in their attempt to destroy Madura by means of the serpent which was turned into the Nāgamalai, resorted to more magic, and evolved a demon in the form of an enormous cow. They selected this particular shape for their demon, because they thought that no one would dare kill so sacred an animal. Siva, however, directed the bull which is his vehicle to increase vastly in size, and go to meet the cow. The cow, seeing him, died of love, and was turned into this hill.”

On the wall of the mantapam of the golden lotus tank (pōthāmaraī) of the Mīnakshi temple at Madura is a series of frescoes illustrating the persecution of the Jains. For the following account thereof, I am indebted to Mr. K. V. Subramania Aiyar. Srī Gnāna Sammandha Swāmi, who was an avatar or incarnation of Subramaniya, the son of Siva, was the foremost of the sixty-three canonised saints of the Saivaite religion, and a famous champion thereof. He was sent into the world by Siva to put down the growing prevalence of the Jaina heresy, and to re-establish the Saivite faith in Southern India. He entered on the execution of his earthly mission at the age of three, when he was suckled with the milk of spirituality by Parvati, Siva’s consort.

He manifested himself first at the holy place Shiyali in the present Tanjore district to a Brāhman devotee named Sivapathābja Hirthaya and his wife, who were afterwards reputed to be his parents. During the next thirteen years, he composed about sixteen thousand thēvaram (psalms) in praise of the presiding deity at the various temples which he visited, and performed miracles. Wherever he went, he preached the Saiva philosophy, and made converts. At this time, a certain Koon (hunch-back) Pāndyan was ruling over the Madura country, where, as elsewhere, Jainism had asserted its influence, and he and all his subjects had become converts to the new faith. The queen and the prime-minister, however, were secret adherents to the cult of Siva, whose temple was deserted and closed. They secretly invited Srī Gnāna Sammandha to the capital, in the hope that he might help in extirpating the followers of the obnoxious Jain religion. He accordingly arrived with thousands of followers, and took up his abode in a mutt or monastery on the north side of the Vaigai river. When the Jain priests, who were eight thousand in number, found this out, they set fire to his residence with a view to destroying him. His disciples, however, extinguished the flames.

The saint, resenting the complicity of the king in the plot, willed that the fire should turn on him, and burn him in the form of a virulent fever. All the endeavours of the Jain priests to cure him with medicines and incantations failed. The queen and the prime-minister impressed on the royal patient the virtues of the Saiva saint, and procured his admission into the palace. When Sammandha Swāmi offered to cure the king by simply throwing sacred ashes on him, the Jain priests who were present contended that they must still be given a chance. So it was mutually agreed between them that each party should undertake to cure half the body of the patient. The half allotted to Sammandha was at once cured, while the fever raged with redoubled severity in the other half. The king accordingly requested Sammandha to treat the rest of his body, and ordered the Jaina priests to withdraw from his presence. The touch of Sammandha’s hand, when rubbing the sacred ashes over him, cured not only the fever, but also the hunched back.

The king now looked so graceful that he was thenceforward called Sundara (beautiful) Pāndyan. He was re-converted to Saivism, the doors of the Siva temple were re-opened, and the worship of Siva therein was restored. The Jain priests, not satisfied with their discomfiture, offered to establish the merits of their religion in other ways. They suggested that each party should throw the cadjan (palm-leaf) books containing the doctrines of their respective religions into a big fire, and that the party whose books were burnt to ashes should be considered defeated. The saint acceding to the proposal, the books were thrown into the fire, with the result that those flung by Sammandha were uninjured, while no trace of the Jain books remained. Still not satisfied, the Jains proposed that the religious books of both parties should be cast into the flooded Vaigai river, and that the party whose books travelled against the current should be regarded as victorious. The Jains promised Sammandha that, if they failed in this trial, they would become his slaves, and serve him in any manner he pleased.

But Sammandha replied: “We have already got sixteen thousand disciples to serve us. You have profaned the name of the supreme Siva, and committed sacrilege by your aversion to the use of his emblems, such as sacred ashes and beads. So your punishment should be commensurate with your vile deeds.” Confident of success, the Jains offered to be impaled on stakes if they lost. The trial took place, and the books of the Saivites travelled up stream. Sammandha then gave the Jains a chance of escape by embracing the Saiva faith, to which some of them became converts. The number thereof was so great that the available supply of sacred ashes was exhausted. Such of the Jains as remained unconverted were impaled on stakes resembling a sūla or trident. It may be noted that, in the Mahābhārata, Rishi Māndaviar is said to have been impaled on a stake on a false charge of theft.

And Rāmanūja, the Guru of the Vaishnavites, is also said to have impaled heretics on stakes in the Mysore province. The events recorded in the narrative of Sammandha and the Jains are gone through at five of the twelve annual festivals at the Madura temple. On these occasions, which are known as impaling festival days, an image representing a Jain impaled on a stake is carried in procession. According to a tradition the villages of Mēla Kīlavu and Kīl Kīlavu near Sōlavandān are so named because the stakes (kīlavu) planted for the destruction of the Jains in the time of Tirugnāna extended so far from the town of Madura.

For details of the literature relating to the Jains, I would refer the reader to A. Guérinot’s ‘Essai de Bibliographie Jaina,’ Annales du Musée Guimet, Paris, 1906.

Jain Vaisya

The name assumed by a small colony of “Banians,” who have settled in Native Cochin. They are said to frequent the kalli (stone) pagoda in the Kannuthnād tāluk of North Travancore, and believe that he who proceeds thither a sufficiently large number of times obtains salvation. Of recent years, a figure of Brahma is said to have sprung up of itself on the top of the rock, on which the pagoda is situated.

History

Devdutt Pattanaik, January 12, 2023: The Times of India

While Vedic culture based on fire rituals consolidated itself in the upper Gangetic plains, in regions we now know as Delhi (Hastinapur), Mathura (Vraja), Ayodhya (Kosala) and Varanasi (Kashi), the more monastic orders of Buddhism and Jainism, collectively known as Shramana, originated in the lower Gangetic plains of Magadha.

Buddha’s enlightenment happened at Gaya, Bihar. Shikharji mountain in Jharkhand is linked to the final release (moksha) of 21 Jinas, who revealed the Jain way in this era. One of them Muni Suvrat lived at the time of Ram, who is a hero even in Jain chronicles.

Buddhism spread across India and beyond, to China, Southeast and Central Asia. Jainism did not follow the same trajectory. It went southwards to Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, and westwards towards Gujarat, but its northern reach was restricted to Hastinapur and Mathura; it did not significantly spread to Gandhara and Kashmir, though the first Jina, Rishabha, is connected with Mount Kailasa, through the mysterious site of Ashtapada.

The wandering monks

We do have stories of naked, wandering ascetics — probably Jain monks — known to the Greeks as gymnosophists, who travelled to Persia and Greece with Alexander’s army. It is said that the army was amazed at the detachment of these ascetics who were willing to fast to death and self-immolate themselves when they felt their work on earth was done. Other than this we do not hear stories of Jains travelling outside of what we call ‘Jambudvipa’ or ‘Bharatavarsha’.

The term ‘Jambudvipa’ is first used to describe India in the Ashokan edicts erected in 3rd century BCE. The Mauryan king was a patron of Buddhism, but his grandfather Chandragupta Maurya, and his grandson Samprapti are identified as Jains in Jain legends. Chandragupta fasted to death in Karnataka region in keeping with extreme Jain monastic practices while Samprati is said to have encouraged Jain monks to travel south to Tamillakam, just as Ashoka sent Buddhist monks to Sri Lanka, The word ‘Bharatavarsha’ to describe India comes from the Hathigumpha inscription in Kalinga (Odisha) of King Kharavela in the 1st Century CE. Kharavela spoke of reclaiming a Jain image from Magadha. He excavated 117 caves for the Jain ascetics to rest.

The Kharavela inscriptions show how Jainism spread south from Bihar towards Kalinga, an important trading port. This makes sense, since most Jains were from the mercantile community. Tamil texts such as Thirukkural dated to 4th century CE make a strong case for vegetarianism and against animal sacrifice, suggesting Jain influence. Tamil works like Jivakachintamani are indicative of the Jain influence, where the main hero, Jivaka, after living a life of sensual, sexual, and violent escapades, becomes a Jain ascetic.

At Madurai is the Samanar (Shramana) hills with caves and images of the Jina where Jain monks rested during the rainy season when travel was forbidden. Sadly, with the rise of Theistic Hinduism in the form of Alvars and Nayamnars, who were passionate devotees of Vishnu and Shiva, we find rising (and rather violent) opposition to Jains around 6th century CE.

During a great famine in Mauryan times, many Jains migrated to the Karnataka region. Jain influence peaked at the time of the Chalukyas and Rashtrakuta kings like Amoghavarsha, around the 7th century. The Rashtrakuta king Indra IV even fasted to death, like Chandragupta of yore. These kings celebrated Jain values by building magnificent basadis (temples) and pillars to the glory of Jina, especially in southern Karnataka. Here in the 10th century was carved the magnificent statue of Baahubali at Shravanabelagola.

But around the 11th century, Jains faced opposition from the saranas, passionate devotees of Shiva, who inspired the later Veerashaiva and Lingayat community. There are stories of Jain temples being claimed by Shiva worshippers. There is the story of one Shiva worshipper challenging Jain monks to emulate his feat of cutting his head and replacing it. The Jains, losing popularity and patronage, chose retreat.

The expansion

Besides its southern spread, Jainism also travelled from Bihar along the tributaries of Ganga and the Narmada northwards and westwards. The earliest Jain images, including the earliest image of Saraswati, comes from a Jain site in Mathura that is 2,000 years old. It is amongst the earliest sculptures of India.

There are suggestions that originally even Jains built stupas like the Buddhists — the stupa-like structure was meant to showcase the act of samavasarana, when the Jina before his release shares his knowledge with the world. He faces all directions and all creatures surround him in concentric circles and are able to understand his words in their own language.

However, Jains stopped building stupas and chose to build temples and pillars and icons instead when, as per legend, Kanishka, the Kushan king, who ruled much of North India 1900 years ago confused a Jain site for a Buddhist site.

The most vibrant Jain community from the 5th century onwards is found in the Gujarat and Rajasthan region, which were major centres of trade with the Middle East. This was the region where Jain ideas were finally put down in writing in Vallabhi 1,500 years ago under the reign of the Maitraka Kings. Besides Bihar, it is in Gujarat and Rajasthan we find the sacred mountains of Jainism — Shatrunjaya or Palitana, Abu, and Girnar.

Girnar is linked to Neminatha, the 22nd Tirthankara, who is a cousin of Krishna. The story goes that Neminarha became an ascetic after he saw animals tied to be slaughtered for his wedding feast. Horrified by this he renounced all sensual and worldly pleasures and retreated to Mount Girnar. Shatrunjaya is where Adinatha gave his first sermon and is linked with the release of the Pandavas who also adopted Jainism as per Jain lore.

This Gujarat and Rajasthan region became the centre of Jain practices due to the rule of Kumarapala Chaulukya, who as per Jain lore converted to Jainism later in his life and banned animal slaughter. There is a Jain story that dealt with the anxiety of having a Jain non-violent king.

In thrall of kings

Kumarapala's kingdom was threatened by a nearby kingdom who were perched to attack, taking advantage of his conversion to Jainism, and thus his practice of non-violence. Anxious, Kumarapala was told by a Jain ascetic that on a given day the rival will die without Kumarapala having to raise his sword.

True to the prophecy, when the rival king was sleeping on his elephant, his gold chain got caught in the branch of a tree, and he was strangled to death! Since Jains strictly followed the Indian practice of not crossing the sea, for fear of pollution, it was only in the 20th century that the Jains moved across the sea to foreign lands and made a mark for themselves in countries like the USA and Japan which now have Jain temples.

Jains have always tried to mingle with the local population since they follow a policy of pluralism (anekantavada). However, in recent times, some have been rather over-aggressive in opposition to butcher communities, in the name of non-violence (ahimsa), which has led to accusations of Islamophobia.

Perhaps now with its peaceful protests against turning Jain pilgrim spots into tourist trails, many young Jains are realising the perils of being too enamoured by aggressive ambitious politicians. Not everyone is Kumarapala and Amoghavarsha or Chandragupta Maurya. Many kings have no qualms about attacking even non-violent ascetics, in the name of religion, in their quest for power.

2014-15: Diksha reaches record numbers

The Times of India, Oct 19 2015

Record number of Jains chose diksha in 2015

Hemali Chhapia-Shah & Bhavika Jain

When the `plastic king' rode on a specially designed `ship' and tossed packets containing gold coins and keys of brand new cars into the crowd in a Ahmedabad ground on May 31, he lived up to his moniker. It was a fitting farewell to the material world for 58-year-old Delhi billionaire Bhanwarlal Doshi. When he took the vow of diksha, the Jain monk Bhavyaratna Vijay Maharajsaheb was born. The business tycoon renounced his multicrore company , his family, his house and all the comforts of the world, even his footwear, before embarking on a journey to live the life of a monk. Come February and nine other high-flying profession als, including doctors, advocates and engineers, will heed to the highest calling of their heart and sign up for monkhood under Namramu niji Maharajsaheb.From August 2014 to August 2015, the Jain community saw the largest count of people taking the vow of diksha or complete renunciation.

When Rupali Jain scored 89% in her class 10 exams, teachers counselled her to take up science and study medicine. Little did they know that she would decide to take diksha.Her friends were surprised, as she was fond of watching films, and like any teenager, used to spent a lot of time in front of the mirror dolling up. “It was like she heard a voice rom inside of her and decided to respond to it,“ said a close relative.

Today, the number of monks from the community stands at 16,000. In 1986, there were 9,426 monks and their numbers rose by a mere 836 over the next decade. This, despite the fact that there are about 1,200 deaths among Jain monks each year.

Equally remarkable is the preponderance of women--three times more than the number of men--taking diksha. Of the 16,008 Jain monks currently living in temples and upashreyas (rooms where monks live and are usually situated close to temples), 12,066 are sadhvis; another 3,942 are maharajsahebs.