Jammu & Kashmir: Social issues

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Language

2019/ Keeping Kashmiri alive

Shobita Dhar, August 11, 2019: The Times of India

From: Shobita Dhar, August 11, 2019: The Times of India

From: Shobita Dhar, August 11, 2019: The Times of India

From: Shobita Dhar, August 11, 2019: The Times of India

Author and anthropologist Onaiza Drabu grew up in Srinagar but never learnt to speak or write in her mother tongue as she was encouraged to learn English because it would help her make a career. However, she felt a void. “I remember at school one of our teachers told us that the definition of a literate person is one who can read and write in her mother tongue, and this hit hard. I could barely speak mine,” recalls Drabu, 29. She resolved to learn more about Kashmiri language and literature. To record all that she learnt, she started The Lipton Chai, a beautifully illustrated blog that explains Kashmiri idioms, abuses and untranslatable words. For example, ‘kaek’, describes someone who incessantly argues, questions, nitpicks and criticises. This year, she published a book for children —Okus Bokus: A to Z for Kashmiri Children — which showcases the Kashmiri way of life through stories woven around a grandmom (naen) and her two little grandkids.

Drabu is one of several young Kashmiris who are trying to keep their language alive. Since it doesn’t have a script, it is best learnt at home from parents and elders. However, years of conflict in the region have resulted in migration of Kashmiris (first Pandits and later even Muslims) to other parts of India and the world. As a result, younger generations of Kashmiris who grew up outside the Valley, mostly speak Hindi and English. In their homes away from home, local breads like ‘girda’ (a fermented, hard bread) have been replaced by the parathas, pizzas and paninis. And Lipton chai (the name by which Kashmiris refer to brewed Darjeeling and Assam varieties) has pushed the salty noon chai and kahwa off the table.

Pragnya Wakhlu, a singer and songwriter, says that every time she visits Srinagar, fewer and fewer people are speaking it. While she grew up in Pune, her grandparents still live near the Dal Lake. She left her IT job in the US to turn fulltime musician so that she could take Kashmiri language and music to more people. The title track of her album, Kahwa Speaks, tells the story of how a cup of fragrant kahwa is prepared in Kashmiri with almonds, saffron and cardamom and then switches to English to explain how life is also a beautiful brew, and like kahwa, made of different identities. “It was important for me to shift the perspective on Kashmir from just conflict and violence to its culture, and help displaced people reconnect with Kashmir and its language,” says Wakhlu, who released the video last year.

Drabu says her book reflects on aspects of Kashmiri culture that fascinated her the most. “These bits of history and culture, often intangible, are mostly lived and, therefore, slowly losing relevance. I have tried to capture the A to Z of being Kashmiri by bringing in aspects of food, flora and fauna, as well as folklore,” she says.

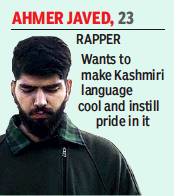

For 23-year-old rapper Ahmer Javed, writing songs in Kashmiri and English is a way to tell people about what’s happening on ground zero. Due to the mobile shutdown, TOI couldn’t speak with Javed, who had flown Delhi to Srinagar to be with this family after the Article 370 news broke. Before boarding his flight, he texted some lines of verse to his friends. “Humare haq mein toh kabhi kuch tha hi hani/ khoon behta hai humara, ye manate khushi/ itni nafrat hai humse par pyaari hai zameen/ Kashmiri na dikhne chahiye inne kahi… (We never had any rights/they celebrate when we bleed/they hate us but love our land/ Kashmiris shouldn’t be visible to them…).

Javed’s debut album, Little Kid, Big Dreams, was released last year by Delhibased Azadi Records. In an interview to Platform magazine, Javed had said, “In Kashmir, especially schools, they teach you to either talk in Hindi or English, we have lost the essence of Kashmiri language. I wanted to show how even rapping in Kashmiri is cool and make everyone feel proud of it and not kill our mother tongue.”

For singer-songwriter Aabha Hanjura, one way to ensure that the language lives on is to reinvent it. Last month she released her new music album, Roshewalla whose first song, Rosh’ e wala myaane dilbaro… is a peppy take on a classic Kashmiri love song that’s played and sung at every marriage and celebration. Her first hit, ‘Hokus bokus…’, released in 2017, did a similar pop makeover of a popular Kashmiri children’s rhyme and became an online hit with 2.9 million views on YouTube. “I have tried to take the language forward in a form that’s easily understood by the younger generation,” says Hanjura, 31, who grew up in Jammu after her family got displaced from Srinagar in the early 90s due to militancy. “I may or may not be in Kashmir but it will always live in my music,” she says.

Marriage

Dr. Kavita Suri , Where are J&K’s eligible bachelors!!! "Daily Excelsior" 18/4/2017

Amid the escalated violence in Jammu and Kashmir in the past few days, there is yet another cause of concern of late. Well, nothing to do with the traditional security issues but something which is non-traditional having a potential to break down our social systems completely. The women of our state are getting married later than women elsewhere in the country, says a latest report released by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, entitled “Women and Men in India-2016”. The report quoting Sample Registration System (SRS) data 2014 says that while the mean age of women at the time of marriage in 21 major Indian states was 22.3 years in 2014, in Jammu and Kashmir it was 25.2 years. Our average age at which women in the state are marrying is nearly 3 years more than the mean age of marriage in India, and a year-and-a-half more than in Kerala – the state with the next highest mean marriage age for women.

While the girls from Jammu and Kashmir are the eldest ones to marry in the entire country, Jharkhand marries its girls at a young age and thus tops the list of those states where daughters are married off very early. Women’s mean age at marriage at all India level was 22.3 years and the same in rural and urban areas are 21.8 years and 23.2 years respectively.

The data shows that the marriage age for girls in J&K was 24.3 in the year 2012, 24.1 in 2013 and 24.9 in 2014 in the rural areas of the state. In the urban centres, the marriage age for girls for 2012 was 26.2, 25.8 in 2013 and 25.8 in 2015. The combined mean age for marriage of girls in J&K is 24.6 for the year 2012, 24.4 in 2013 and 25.2 for 2014. No data is available for 2010 and 2011.

For our state of Jammu and Kashmir, this is not the new phenomenon. The reports that the late marriages especially that of the girls were becoming very common in the valley, started emerging as early as the year 2000 and were often linked to conflict, poverty, killing of the young boys of marriageable age.

The well known late sociologist of Kashmir University Prof Bashir Dabla with whom I used to interact a lot in KU Campus, had researched that the marriage age of boys in Kashmir had risen to 31 years and 27 in females. This he had found out, was clearly linked with the socio-economic and educational-political developments in Jammu and Kashmir which had greatly been impacted by the protracted conflict in Kashmir. This indeed was a matter of concern.

The protracted armed conflict in Kashmir was often linked to this phenomenon. In these past 27 years of armed conflict in valley, not only the boys belonging to affluent families moved out of the valley for better avenues but those who were left behind, were caught in the conflict. Many of them were lured by the call for Azadi and crossed over to the other side for Jihad; thousands got killed, hundreds disappeared and those who were left behind were the ones most sought after for marriages, thus what we witnessed was a higher demand for dowry.

On the other hand, the girls who were left to fend for themselves with their widowed mothers were vulnerable, had to quit their studies and thus could neither get educated nor get a job. This was quite visible during my own field research in Kashmir valley first as a journalist and then as a peace scholar in 2005 when I got a fellowship by Women in Security, Conflict Management and Peace (WISCOMP), an initiative by the Dalai Lama Foundation on the theme “Impact of violence on girls’ education in Kashmir valley’. The related field research made me witness these harsh realities on ground myself.

The teenage girls had no security, no education, no adequate livelihoods, their mothers were surviving solely on Zakat or some help from some charity organizations. And many of them were of marriageable age but there were no takers as they were poor. The teenage uneducated girls in rural Kashmir were helping their mothers with household chores and taking care of their younger siblings.

Almost 12 years have gone by since my Study but the situation is still very bad. It is the matter of grave concern that a big chunk of our female population could not marry on time. Conflict situations not only aggravated acute poverty, dowry demands also got increased, education became a dream for the girls and unemployment also became common. Strangely, another phenomenon was witnessed in city centres; those girls who got educated and even got jobs, waited for the right matches which never came. Thus, they had to ‘compromise’ and marry those boys who had less qualification or even no match to their families or even their own earnings.

Though armed conflict, unemployment and education are attributed to be few of the reasons for the late marriages in the state, the extravaganza in the marriages, dowry system, etc have contributed to the same in a big way. Thankfully, the state government has finally woken up to the fact that this is creating social issues and thus the ban on marriage extravaganza has come into place from Ist April this year.

The issue has other moral, ethical, cultural and social serious implications. The sociologists in Kashmir had already been advocating that the issue of late marriages has the potential to damage the social fabric of the society and in the course of one such discussions, Prof Dabla referred to the issue like immoral activities and prostitution in the state as an “inferno”. Much before the surfacing of sex scam in Kashmir valley in 2006, he had told me that this ‘inferno” is going to engulf the entire region. Indeed, it did. The entire issue rocked the valley for a pretty long time and dominated political scene too. Late marriages do alter social fabric with pre-marital and extra-marital affairs creeping into the society. Late marriage and sexual promiscuity cannot be avoided in a conflict situation. Besides, the psychological aspect of late marriage is also very alarming including depression, increase in suicide rate, emerging immoral activities. Then, the children born to late married couples have higher chances of carrying congenital diseases or birth defects.

What is needed is a strong collective response from all the stakeholders to deal with the issue seriously and sincerely. The Jammu and Kashmir State Women Commission, under its chairperson Ms Nayeema Mahjoor has already started a massive campaign in the entire state regarding women’s issues which are otherwise brushed aside as non-issues without even considering the fact that society is at the brink of social degradation. Besides, the SCW is also working on a proposal of constituting a competent religious authority that will have the authority to decide on martial disputes like marriage/ remarriage, separation and right of women to divorce etc. Whatever the methods and processes, we need to act quick if we have to restore the fabric of our society.

(The author is Director and head, Department of Lifelong Learning, University of Jammu and Member, J&K State Commission for Women)