Jharia

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents[hide] |

Jharia

Coal-field in Manbhum District, Bengal. See Manbhum.

Jharia

(From People of India/ National Series Volume VIII. Readers who wish to share additional information/ photographs may please send them as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.)

Synonyms: Mehra [Madhya Pradesh and/or Chhattisgarh] Groups/subgroups: Amodha, Dahia, Deharia, Mahobia [ Madhya Pradesh and/or Chhattisgarh] Titles: Choudhury [Madhya Pradesh and/or Chhattisgarh] Surnames: Jharia [Madhya Pradesh and/or Chhattisgarh] Exogamous units/clans: Chandel, Chandhury, Gohia, Nag (cobra), Nagbanshi, Padya, Sagar, Suryabanshi [Madhya Pradesh and/or Chhattisgarh]

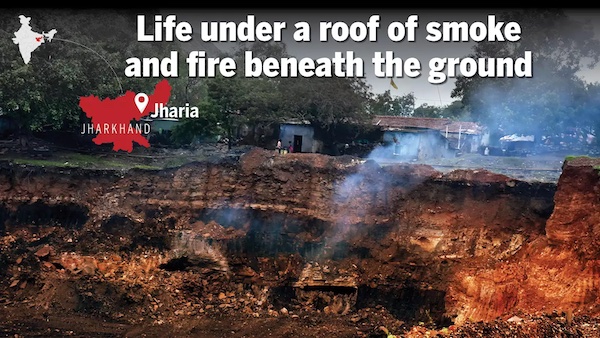

Underground fires

As in 2019

ASRP Mukesh ,Photos by Mahadeo Sen, September 19, 2019: The Times of India

From: ASRP Mukesh ,Photos by Mahadeo Sen, September 19, 2019: The Times of India

In June 2017, teenager Rahim Khan and his father Bablu Khan, aged 40, opened their front door only to be sucked into a gaping sinkhole right outside, caused by the underground fire raging beneath, in a place called Phulbaribag, deep inside India’s largest coalfield in Jharia.

Just about a fortnight ago, a little past midnight, in village Liloripathra, just 4 km from Phulbaribag, Meena Devi and her family – her husband and a teenage son — were shaken awake by a deafening thud. She immediately knew a piece of land had caved in somewhere close. She managed to scurry off her cot along with the two before a part of her roof collapsed on it due to the shaking ground.

Accidents and untimely deaths are not uncommon in the 70-odd villages across the 208 sq km area, about the size of Kolkata, in the heart of India’s coal industry. Jharia’s underground fires that have been burning the coal beneath for more than a hundred years were first detected in 1916 and the Khas Jharia mines were the first to collapse in 1930. Experts believe the fires spread faster after the 1934 Indo-Nepal earthquake. In 2009, the Centre approved a Jharia Masterplan designed in 2004 for the rehabilitation and resettlement of the people who lived around the burning mines by 2021. Little has moved though the deadline is barely 24 months away and there are over a lakh families to be resettled. The Supreme Court on July 16 this year appointed advocate Gaurav Agrawal as amicus curiae in the case. The Amicus curiae submitted his report on rehabilitation of residents in Jharia's burning coalfields on August 31. The report finds the masterplan of 2004 wanting on several aspects. It raises concerns over inadequate compensation amounts and availability of land for the rehabilitation, and squarely places the onus of securing alternative livelihood on governments at the Centre and state.

The dwellers at the Jharia mines are caught between an uncertain future and hellfire. But nothing about Meena Devi (42) gives away the fact she is lucky to be alive. Her clean saree, tidy hair and calm demeanour do not reflect the apocalyptic landscape in which she lives. She is just grateful nobody died that day. The family rebuilt their two-room mud hut within days and life went on. “Such incidents aren’t new to us…We shifted to a place nearby for a couple of days and returned when the house was repaired,” says Meena, burning the coal stocks, which they scavenged from an open cast mine site. Liloripathra is on the edge of a 700-feet deep open-pit coal mine. Shrouded in dust, it is being consumed by the underground fires. On a rainy day, thick smoke engulfs the area. When the skies clear, large columns of underground fires become visible as smoke billows from beneath.

While government had rolled out Jharia Masterplan in 2009 to rehabilitate and resettle people from the fire-affected zones, the Khan father-son duo’s death in 2017 forced district administration and Bharat Coking Coal Limited (BCCL), a subsidiary of Coal India, which owns these mines, to move the three dozen families from Phulbaribag to another place. They were eventually settled at quarters allotted in Jharia Vihar in Belgaria, a township constructed by Jharia Rehabilitation Development Authority (JRDA) 10km away. Two years on, many of these families are back in Phulbaribag, living in makeshift houses. “We’d rather die here than live in Belgaria,” says Bablu’s maternal aunt Tajo Khatoon (70). “They allotted a one-room quarter for our family of 20. If not of congestion, we would have died of starvation as we had no work.” The family has given out the quarter on rent and have no plans to return. The exposure to underground fires and the smoke have led to degradation of soil, air and water. Several locals complain of persistent coughs, headaches and pain in the chest. Respiratory diseases like tuberculosis and bronchitis are common here. People suffer every day, but refuse to move out. Like hundreds in this area, Khatoon’s neighbour Sakina Begum suffers from lung disease and respiratory illnesses, but she will never go back to Belgaria. “Our livelihoods are here. We work as domestic helps and daily wagers. I ended up spending Rs 30 a day travelling to and from Belgaria. What would I save and how would feed my family?” asks Begum. Her husband, Md Mustafa Ansari (65), said they were allotted a quarter on the fourth floor. “I can’t climb that many stairs as I too suffer from respiratory problems. I don’t mind dying here, but I’ll not go anywhere unless proper arrangements are made,” he says.

In some villages, like Morhiband, where people are keen to be shifted out, they are waiting to hear from the authorities. Sitting in a makeshift shelter near the debris of his house that collapsed last year, Ramesh Bhuiyan says, “A few officials had come to the village for a survey two weeks ago, but they could not tell us when we would get our house.” Staring at the smoke billowing out of the fissures on the ground, Bhuiyan adds, “I will go as soon as I get a house. Who really wants to die a slow, painful death,” he says.

There are few options available for locals looking for a better life and activists say utmost urgency is needed to save the people from the ticking time bomb.

“We are heading towards a massive manmade human tragedy. Entire Jharia will be wiped out as neither BCCL nor JRDA are serious about their jobs,” says Ashok Agarwal, president of Jharia Coalfields Bachchao Samiti, which moved a PIL in late 1990s, to prevent BCCL from outsourcing its mining activities. “BCCL’s primary objective is to maximise the amount of coal they extract, irrespective of its impact on the population,” he says. In 2004, JRDA was established and the Jharia Masterplan was prepared later that year. As per the plan, 24,000 encroachers (households) and 29,444 legal title holders (LTH) would have to be rehabilitated. With the passage of time, the numbers have increased manifold. JRDA’s rough estimate now suggests that 1,41,946 families -- including 69,000 LTH -- have to be rehabilitated. “Barely 2,600 non-LTH families have been shifted since 2009 while LTHs have not been touched. The survey has just begun,” Agarwal says. Social activist and Jharia resident Pinaki Roy says “The masterplan does not talk of rehabilitation of those living as tenants in this area. Where will someone living here for 20 years go? Moreover, whatever they (JRDA) are offering in Belgaria isn’t rehabilitation or resettlement. They just want people to leave without basic life support,” he says.

JRDA rehabilitation and resettlement in-charge Azfer Hasnain agrees that the progress has been tardy, but maintains that efforts to pace up the work started a year ago on. According to JRDA, of the 595 identified sites for rehabilitation, survey to identify households is complete in 573 areas while it is yet to begin in 11 sites. “These 11 sites are under the jurisdiction of West Bengal (Burdwan district). We contacted the Bengal authorities many times, but there was no response. We recently got in touch with them again,” Hasnain says. “So far we have rehabilitated 3,500 non-LTH households and another 18,000 houses are under various phases of construction to move the others,” he adds. Hasnain however accepts that there are challenges ahead. “Non-LTH households are returning to the fire-affected zones for some reason or another. We need to devise a monitoring mechanism to prevent that. Meanwhile, LTH folks are not accepting our rehabilitation package as we are only offering twice the land’s value. A decision has to be taken at the Centre to resolve these issues. As far as livelihood for those rehabilitated, deliberations are on to sort out the issues,” he says.

A fire rages under their home

2004

Jharia Rehabilitation Development Authority (JRDA) established. The masterplan was prepared later that year — 24,000 ‘encroachers’ (households) and 29,444 legal title holders (LTH) were to be rehabilitated

2009

The Centre approved the masterplan allocating Rs 7,112.11cr to rehabilitate & resettle people from fire-affected zones in 10 years, excluding two years of pre-rehabilitation works. The deadline was fixed for 2021

2019

With time, numbers have increased. JRDA’s estimates suggest 1,41,946, including 69,000 title holders, to be rehabilitated

As the 2021 deadline nears, progress remains tardy

On July 9, Supreme Court prioritised the case pending before it since 1997. On July 16, it appointed an amicus curie, asking him to submit a ground report in four weeks

As per current official data, fires rage beneath the ground at 67 different locations. No one is aware about the intensity of the underground fires below the Earth