Jodhpur State , 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Jodhpur State

Physical aspects

Marwar). — The largest State in Rajputana, having an area of 34,963 square miles, or more than one- fourth of the total area of the Agency. It lies between 24 degree 37' and 2 7 degree 42' N. and 70 degree 6' and 75 degree 22' E. It is bounded on the north by Blkaner ; on the north-west by Jaisalmer ; on the west by Sind ; on the south-west by the Rann of Cutch ; on the south by Palanpur and Sirohi ; on the south-east by Udaipur ; on the east by Ajmer-Merwara and Kishangarh ; and on the north-east by Jaipur.

The country, as

its name Marwar (= 'region of death') implies,

is sterile, sandy, and inhospitable. There are some aspects

comparatively fertile lands in the north-east, east,

and south-east in the neighbourhood of the Aravalli Hills ; but,

generally speaking, it is a dreary waste covered with sandhills, rising

sometimes to a height of 300 or 400 feet, and the desolation becomes

more absolute and marked as one proceeds westwards. The northern

and north-western portion is a mere desert, known as the thai, in

which, it has been said, there are more spears than spear-grass heads,

and blades of steel grow better than blades of corn.

The country here

resembles an undulating sea of sand ; an occasional oasis is met with,

but water is exceedingly scarce and often 200 to 300 feet below the sur-

face. The Aravalli Hills form the entire eastern boundary of the

State, the highest peak within Jodhpur limits being in the south-east

(3,607 feet above the sea). Several small offshoots of the Anivallis

lie in the south, notably the Sunda hills (Jaswantpura), where a height

of 3,252 feet is attained, the Chappan-ka-pahar near Siwana (3,199

feet), and the Roja hills at Jalor (2,408 feet). Scattered over the State

are numerous isolated hills, varying in height from 1,000 to 2,000 feet.

The only important river is the Luni. Its chief tributaries are the Lllri, the Raipur Luni, the Guhiya, the Bandi, the Sukri, and the Jawai on the left bank, and the Jojri on the right. The principal lake is the famous salt lake at Sambhar. Two other depressions of the same kind exist at Dldwana and Pachbhadra. There are a few /Mis or marshes, notably one near Bhatki in the south-west, which covers an area of 40 or 50 square miles in the rainy season, and the bed of which, when dry, yields good crops of wheat and gram.

A large part of the State is covered by sand-dunes of the transverse type, that is, with their longer axes at right angles to the prevailing wind. Isolated hills of solid rock are scattered over the plain. The oldest rocks found are schists of the Aravalli system, and upon them rests unconformably a great series of ancient subaerial rhyolites with subordinate bands of conglomerate, the Mallam series. These cover a large area in the west and extend to the capital. Coarse-grained granites of two varieties, one containing no mica and the other both hornblende and mica, are associated with the rhyolites. Near the capital, sandstones of Vindhyan age rest unconformably upon the rhyolites. Some beds of conglomerate, showing traces of glacial action, have been found at Pokaran and are referred to the T&lcher period. Sandstones and conglomerates with traces of fossil leaves occur at Barmer, and are probably of Jurassic age. The famous marble quarries of Makrana are situated in Jodhpur territory, the marble being found among the crystalline Aravalli schists.

The eastern and some of the southern districts are well wooded with natural forests, the most important indigenous timber-tree being the babul (Acacia arabka) the leaves and pods of which are used as fodder in the hot season, while the bark is a valuable tanning and dyeing agent.

Among other trees may be mentioned the tnahua (Bassia

latifolia) valuable for its timber and flowers; the anwal (Cassia

auriculala), the bark of which is largely used in tanning ; the dhak or

palds (Butea frondosa), the dhao (Anogeissus pendula) the gular (Ficus

glomeratd)) the siris (Albizzia Lebbck), and the khair (Acacia Catechu).

Throughout the plains the kheira (Prosopis spicigera) the rohra (Tecoma

Undulate ), and the nltn (Melia Azadirachtd) are common, and the

tamarind and the bar (Ficus bengaiensis) are fairly so.

The papal (Ficus

religious ),a sacred tree, is found in almost every village. The principal

fruit trees are the pomegranate (Punica Granatutn), the Jodhpur variety

of which is celebrated for its delicate flavour, and the nlmbu or lime-

tree. In the desert the chief trees are two species of the ber (Zizyphus

Jujuba and Z. nummularia), which flourish even in years of scanty

rainfall, and furnish the main fodder and fruit-supply of this part of the

country ; and the kkejra, which is not less important, as its leaves and

shoots provide the inhabitants with vegetables (besides being eaten by

camels, goats, and cattle), its pods are consumed as fruits, its wood is

used for roofs, carts, and agricultural implements or as fuel, and its

fresh bark is, in years of famine, stripped off and ground with grain to

give the meagre meal a more substantial bulk.

The fauna is varied. Lions are now extinct, the last four having been shot near Jaswantpura about 1872, and the wild ass (Equus hemionus) is seldom, if ever, seen. Tiger, sambar (Cervus unicolor), and black bears are found in the Aravallis and the Jaswantpura and Jalor hills, but in yearly decreasing numbers. Wild hog are fairly numerous in the same localities, but are scarcer than they used to be in the low hills adjacent to the capital.

Leopards and hyenas are

generally plentiful, and nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus) are found in

some of the northern and eastern districts. Indian gazelle abound

in the plains, as also do antelope, save in the actual desert; but the

chiial (Cervus axis) is seen only on the slopes of the Aravallis in

the south-east. Wolves are numerous in the west, and wild dogs are

occasionally met with in the forests. In addition to the usual small

game, there are several species of sand-grouse (including the imperial),

and two of bustard, namely, the great Indian (Eupodotis edwardsi)

and the houbara (Houbara macqueent).

The climate is dry, even in the monsoon period, and characterized by extreme variations of temperature during the cold season. The hot months are fairly healthy, but the heat is intense ; scorching winds prevail with great violence in April, May, and June, and sand-storms are of frequent occurrence. The climate is often pleasant towards the end of July and in August and September ; but a second hot season is not uncommon in October and the first half of November.

In the

cold season (November 15 to about March 15) the mean daily range

is sometimes as much as 30 , and malarial and other fevers prevail.

An observatory was opened at Jodhpur city in October, 1896, and the

average daily mean temperature for the nine years ending 1905 has

been nearly 81° (varying from 62-7° in January to 94-2° in May).

The mean daily range is about 25 (16'6° in August and 30-5° in

November). The highest temperature recorded since the observatory

was established has been 121 on June 10, 1897, and the lowest 28

on January 29, 1905.

The country is situated outside the regular course of both the south- west and north-east monsoons, and the rainfall is consequently scanty and irregular. Moreover, even in ordinary years, it varies considerably in different districts, and is so erratic and fitful that it is a common saying among the village folk that 'sometimes only one horn of the cow lies within the rainy zone and the other without.'

The annual

rainfall for the whole State averages about 13 inches, nearly all received

in July, August, and September. The fall varies from less than

7 inches at Sheo in the west to about 13 inches at the capital, and

nearly i8£ inches at Jaswantpura (in the south) and Bali in the south-

east. The heaviest fall recorded in any one year was over 55^ inches

at Sanchor (in the south-west) in 1893, whereas in 1899 two of the

western districts (Sheo and Sankra) received but 0-14 inch each.

History

The Maharaja of Jodhpur is the head of the Rathor clan of Rajputs, and claims descent from Rama, the deified king of Ajodhya. The original name of the clan was Rashtra (' protector '), and subsequently eulogistic suffixes and prefixes were attached, such as Rashtrakuta (kuta = ' highest ') or Maharashtra (maha = ' great '), &c. The clan is mentioned in some of Asoka's edicts as rulers of the Deccan, but their earliest known king is Abhimanyu of the fifth or sixth century a.d., from which time onward their history is increasingly clear.

For nearly four centuries preceding

a.d. 973 the Rashtrakutas gave nineteen kings to the Deccan ; but in

the year last mentioned they were driven out by the Chalukyas (Solanki

Rajputs) and sought shelter in Kanauj, where a branch of their family

is said to have formed a settlement early in the ninth century. Here,

after living in comparative obscurity for about twenty-five years, they

dispossessed their protecting kinsmen and founded a new dynasty

known by the name of Gaharwar.

There were seven kings of this

dynasty (though the first two are said to have never actually ruled over

Kanauj), and the last was Jai Chand, who in 1194 was defeated by

Muhammad Ghori, and, while attempting to escape, was drowned in

the Ganges. The nearer kinsmen of Jai Chand, unwilling to submit

to the conqueror, sought in the scrub and desert of Rajputana a second

line of defence against the advancing wave of Muhammadan conquest.

Siahjf, the grandson (or, according to some, the nephew) o( Jai Chand,

with about 200 followers, ‘ the wreck of his vassalage’ accomplished

the pilgrimage to Dwarka, and is next found conquering Kher

(in Mallani) and the neighbouring tract from the Gohel Rajputs, and

planting the standard of the Rathors amidst the sandhills of the Luni

in 1 2 12.

About the same time a community of Brahmans held the

city and extensive lands of Pali, and, being greatly harassed by Mers,

Bhils, and Mints, invoked the aid of Siahjl in dispersing them. This

he readily accomplished ; and, when subsequently invited to settle in

the place as its protector, celebrated the next Holl festival by putting

to death the leading men, and in this way adding the district to his

conquests. The foundation of the State now called Jodhpur thus

dates from about 1 2 1 2 ; but this was not the first appearance of the

Rathors in Marwar, for, as the article on Bali shows, five of this clan

ruled at Hathundi in the south east in the tenth century.

In Siahjfs

time, however, the greater part of the country was held by Parihar,

Gohel, Chauhan, or Paramara Rajputs. The nine immediate successors

of Siahjl were engaged in perpetual broils with the people among

whom they had settled, and in 1381 the tenth, Rao Chonda, accom-

plished what they had been unable to do. He took Mandor from the

Parihtr chief, and made his possession secure by marrying the latter's

daughter. This place was the Rathor capital for the next seventy-eight

years, and formed a convenient base for adventures farther afield,

which resulted in the annexation of Nagaur and other places before

the Rao's death about 1409. His son and successor, Ran Mai, who

was a brother-in-law of Rana Lakha, appears to have spent most

of his time at Chitor, where he interfered in Mewar politics and was

assassinated in an attempt to usurp the throne of the infant Rana

Kumbha.

The next chief was Rao Jodha, who, after annexing Sojat

in 1455, laid the foundation of Jodhpur city in 1459 and transferred

thither the seat of government. He had fourteen (or, according to

some authorities, seventeen) sons, of whom the eldest, Satal, succeeded

him about 1488, but was killed three years later in a battle with the

SubahdSr of Ajmer, while the sixth was Blka, the founder of the

Blkaner State. Satal was followed by his brother Suja, remembered

as the 'cavalier prince,' who in 15 16 met his death in a fight with the

Pathans at the Pipar fair while rescuing 140 Rathor maidens who were

being carried off. Rao Ganga (1516-32) sent his clansmen to fight

under the standard of Mewar against the Mughal emperor, Babar, and

on the fatal field of Khanua (1527) his grandson Rai Mai and several

other Rathors of note were slain.

Rao Maldeo (1532-69) was styled by Firishta 'the most powerful prince in Hindustan'; he conquered and annexed numerous districts and strongholds, and, in his time, Marwar undoubtedly reached its zenith of power, territory, and independence. When the emperor Humayun was driven from the throne by Sher Shah, he sought in vain the protection of Maldeo ; but the latter derived no advantage from this inhospitality, for Sher Shah in 1544 led an army of 80,000 men against him.

In the engagements that ensued the Afghan was very nearly beaten, and his position was becoming daily more critical, till at last he had recourse to a stratagem which secured for him so narrow and barren a victory that he was forced to declare that he had ( nearly lost the empire of India for a handful of bajra’ — an allusion to the poverty of the soil of Marwar as unfitted to produce richer grain. Subsequently Akbar invaded the country and, after an obstinate and sanguinary defence, captured the forts of Merta and Nagaur.

To

appease him, Maldeo sent his second son to him with gifts; but the

emperor was so dissatisfied with the disdainful bearing of the desert

chief, who refused personally to attend his court, that he besieged

Jodhpur, forced the Rao to pay homage in the person of his eldest son,

Udai Singh, and even presented to the Bikaner chief, a scion of the

Jodhpur house, a formal grant for the State of Jodhpur together with

the leadership of the clan. Rao Maldeo died shortly afterwards ; and

then commenced a civil strife between his two sons, Udai Singh and

Chandra Sen, ending in favour of the latter, who, though the younger,

was the choice of both his father and the nobles. He, however, ruled

for only a few years, and was succeeded (about 1581) by his brother,

who, by giving his sister, Jodh Bai, in marriage to Akbar, and his

daughter Man Bai to the prince Salim (Jahanglr), recovered all the

former possessions of his house, except Ajmer, and obtained several

rich districts in Malwa and the title of Raja.

The next two chiefs,

Sur Singh (1595-16 20) and Gaj Singh (1620-38), served with great

distinction in several battles in Gujarat and the Deccan. The brilliant

exploits of the former gained for him the title of Sawai Raja, while

the latter, besides being viceroy of the Deccan, was styled Dalbhanjan

(or ' destroyer of the army ') and Dalthambhan (or ‘ leader of the host ').

Jaswant Singh (1638-78) was the first ruler of Marwar to receive the

title of Maharaja. His career was a remarkable one. In 1658 he was

appointed viceroy of Malwa, and received the command of the army

dispatched against Aurangzeb and Murad, who were then in rebellion

against their father.

Being over-confident of victory and anxious to

triumph over two princes in one day, he delayed his attack until they

had joined forces, and in the end suffered a severe defeat at Fatehabad

near Ujjain. Aurangzeb subsequently sent assurances of pardon to

Jaswant Singh, and summoned him to join the army then being

collected against Shuja. The summons was obeyed, but as soon as the

battle commenced he wheeled about, cut to pieces Aurangzeb's rear-

guard, plundered his camp, and marched with the spoils to Jodhpur.

Later on he served as viceroy of Gujarat and the Deccan, and finally in

1678, in order to get rid of him, Aurangzeb appointed him to lead an

army against the Afghans. He died in the same year at Jamrud, and

was succeeded by his posthumous son, Ajit Singh, during whose infancy

Aurangzeb invaded Marwar, sacked Jodhpur and all the large towns,

destroyed the temples and commanded the conversion of the Rathor

race to Islam.

This cruel policy cemented into one bond of union all who cherished either patriotism or religion, and in the wars that ensued the emperor gained little of either honour or advantage. On Aurang- zeb's death in 1707 Ajlt Singh proceeded to Jodhpur, slaughtered or dispersed the imperial garrison, and recovered his capital. In the fol- lowing year he became a party to the triple alliance with Udaipur and Jaipur to throw off the Muhammadan yoke. One of the conditions of this alliance was that the chiefs of Jodhpur and Jaipur should regain the privilege of marrying with the Udaipur family, which they had forfeited by contracting matrimonial alliances with the Mughal emperors, on the understanding that the offspring of Udaipur princesses should suc- ceed to the State in preference to all other children. The allies fought a successful battle at Sambhar in 1709, and a year or so later forced Bahadur Shah to make peace.

When the Saiyid brothers — 'the Warwicks of the East’ — were in power, they called upon Ajlt Singh to mark his subservience to the Delhi court in the customary manner by sending a contingent headed by his heir to serve. This he declined to do, so his capital was in- vested, his eldest son (Abhai Singh) was taken to Delhi as a hostage, and he was compelled, among other things, to give his daughter in mar- riage to Farrukhsiyar and himself repair to the imperial court. For a few years Ajlt Singh was mixed up in all the intrigues that occurred ; but on the murder of Farrukhsiyar in 17 19, he refused his sanction to the nefarious schemes of the Saiyids, and in 1720 returned to. his capital, leaving Abhai Singh behind.

In 172 1 Ajlt Singh seized Ajmer, where he coined money in his own name, but had to surrender the place to Muhammad Shah two years later. In the meantime, Abhai Singh had been persuaded that the only mode of arresting the ruin of the Jodhpur State and of hastening his own elevation was the murder of his father ; and in 1724 he induced his brother, Bakht Singh, to commit this foul crime. Abhai Singh ruled for about twenty-six years, and in 1731 rendered great service to Muhammad Shah by capturing Ahmadabad and suppressing the rebellion of Sarbuland Khan.

On his death in 1750 his son Ram Singh succeeded, but was soon ousted by his uncle, Bakht Singh, the parricide, and forced to flee to Ujjain, where he found Jai Appa Sindhia and concerted measures for the invasion of his country. In the meantime Bakht Singh had met his death, by means, it is said, of a poisoned robe given him by his aunt or niece, the wife of the Jaipur chief ; and his son, Bijai Singh, was ruling at Jodhpur. The MarSthas assisted Ram Singh to gain a victory over his cousin at Merta about 1756 ; but they shortly afterwards abandoned him, and wrested from Bijai Singh the fort and district of Ajmer and the promise of a fixed triennial tribute.

After this, Mirwar enjoyed several

years of peace, until the rapid strides made by the Marathas towards

universal rapine, if not conquest, compelled the principal Rajput States

(Mewar, Jodhpur, and Jaipur) once more to form a union for the

defence of their political existence. In the battle of Tonga (1787)

Sindhia was routed, and compelled to abandon not only the field but

all his conquests (including Ajmer) for a time.

He soon returned, how-

ever; and in 1790 his army under De Boigne defeated the Rajputs in

the murderous engagements at Patan (in June) and Merta (in Septem-

ber). In the result, he imposed on Jodhpur a fine of 60 lakhs, and

recovered Ajmer, which was thus lost for ever to the Rathors. Bijai

Singh died about 1793, and was succeeded by his grandson, Bhlm

Singh, who ruled for ten years.

At the commencement of the Maratha War in 1803 Man Singh was chief of Jodhpur, and negotiated first with the British and subsequently with Holkar. Troubles then came quickly upon Jodhpur, owing to in- ternal disputes regarding the succession of Dhonkal Singh, a supposed posthumous son of Bhim Singh, and a disastrous war with Jaipur for the hand of the daughter of the Maharana of Udaipur.

The freebooter

Amir Khan espoused first the cause of Jaipur and then that of Jodhpur,

terrified Man Singh into abdication and pretended insanity, assumed

the management of the State itself for two years, and ended by plunder-

ing the treasury and leaving the country with its resources completely

exhausted. On Amir Khan's withdrawal in 181 7, Chhatar Singh, the

only son of Man Singh, assumed the regency, and with him the British

Government commenced negotiations at the outbreak of the Pindari

War. A treaty was concluded in January, 1 818, by which the State

was taken under protection and agreed (1) to pay an annual tribute of

Rs. 1,08,000 (reduced in 1847 to Rs. 98,000, in consideration of the

cession of the fort and district of Umarkot), and (2) to furnish, when

required, a contingent of 1,500 horse (an obligation converted in 1835

to an annual payment of Rs. 1,15,000 — see the article on Erinpura).

Chhatar Singh died shortly after the conclusion of the treaty, whereupon

his father, Man Singh, threw off the mask of insanity and resumed the

administration.

Within a few months he put to death or imprisoned

most of the nobles who, during his assumed imbecility, had shown any

unfriendly feeling towards him ; and many of the others fled from

his tyranny and appealed for aid to the British, with the result that in

1824 the Maharaja was obliged to restore the confiscated estates of

some of them. In 1827 the nobles again rebelled, and putting the pre-

tender, Dhonkal Singh, at their head, prepared to invade Jodhpur from

Jaipur territory. Lastly, in 1839, the misgovernment of Man Singh and

the consequent disaffection and insurrection in the State reached such

a pitch that the British Government was compelled to interfere.

A

force was marched to Jodhpur, of which it held military occupation for

five months, when Man Singh executed an engagement to ensure future

good government. He died in 1843, leaving no son ; and by the choice

of his widows and the nobles and officials of the State, confirmed by

Government, Takht Singh, chief of Ahmadnagar, became Maharaja of

Jodhpur, the claims revived by Dhonkal Singh being set aside. The

Maharaja did good service during the Mutiny, but the affairs of Marwar

fell into the utmost confusion owing to his misrule, and the Government

of India had to interfere in 1868.

In 1870 he leased to Government

the Jodhpur share of the Sambhar Lake, together with the salt marts of

Nawa and Gudha. Takht Singh died in 1873, when he was succeeded

by his eldest son, Jaswant Singh. The new administration was dis-

tinguished by the vigour and success with which dacoities and crimes of

violence (formerly very numerous) were suppressed, by pushing on the

construction of railways and irrigation works, improving the customs

tariff, introducing a regular revenue settlement, &c. In fact, in every

department a wise and progressive policy was pursued. No chief could

have better upheld the character of his house for unswerving loyalty to

Government, and the two fine regiments of Imperial Service cavalry

raised by him are among the evidences of this honourable feeling.

He

was created a G.C.S.I. in 1875, and subsequently his salute (ordinarily

17 guns) was raised first to 19, and next to 21 guns. He died in 1895,

leaving a strong and sound administration to his only son, Sardar Singh,

who was born in 1880, and is the present Maharaja. He was invested

with powers in 1898, the administration during his minority having been

carried on by his uncle, Maharaj Pratap Singh (now the Maharaja of

Idar), assisted by a Council. The chief events of His Highness's rule

have been : the employment of a regiment of his Imperial Service

Lancers on the north-west frontier in 1897-8 and in China in 1 900-1 ;

the extension of the railway to the Sind border and thence to Hyder-

abad ; the great famine of 1899-1900 ; the conversion of the local into

British currency in 1900 ; and his visit to Europe in 1901. Maharaja

Sardar Singh was a member of the Imperial Cadet Corps from January,

1902, to August, 1903.

The State is rich in antiquarian remains ; the most interesting are de- scribed in the articles on Bali, Bhinmal, Didwana, Jalor, Mandor, Nadol, Nagaur, Pali, Ranapur, and Sadri.

Population

Excluding the 21 villages situated in the British District of Merwara, which, under an arrangement made in 1885, are administered by the Government of India, but over which the Jodhpur Darbar still retains other rights, there were, in 1901,. 4,057 towns and villages in the State, the town of Sambhar being under the joint jurisdiction of the Jodhpur and Jaipur Darbars. The popu- lation at each of the three enumerations was: (1881) i,757,68i, (1891) 2,528,178, and (1901) 1,935,565.

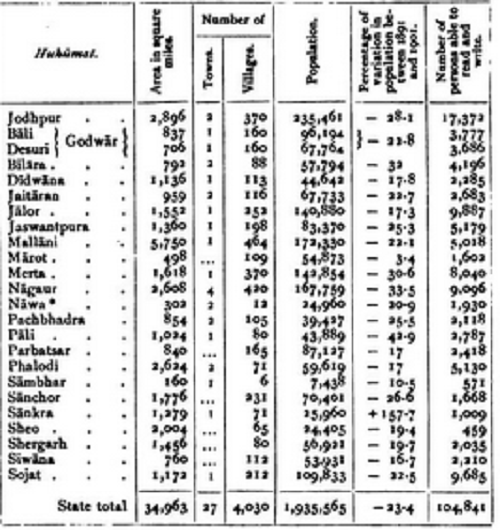

The territory in 1901 was divided into 24 districts or hukumats (since reduced to 23), and contained one city, Jodhpur (population, 79,109), the capital of the State and a munici- pality, and 26 towns. The principal towns are Phalodi (population, 13,924) and Nagaur (13,377) in the north, Pali (12,673) and Sojat (11,107) in the east, and Kuchawan (10,749) in the north-east. The following table gives the chief statistics of population in 1901 : —

- Amalgamated with Sambhar in 1903-3.

The large decrease in the population since 1891 was due to a series of bad seasons culminating in the great famine of 1899- 1900, and also to heavy mortality from cholera and fever at the end of the decade. The enormous increase in the population of the Sankra district is ascribed mainly to the immigration of Bhati Rajputs and others from Jaisalmer, while the small decreases in the Marot and Sambhar districts (both in the north-east) seem to show that the famine was less severely felt there.

Of the total population, 1,606,046, or nearly 83 per cent,

are Hindus; 149,419, or nearly 8 per cent, Musalmans; 137,393, or

7 per cent., Jains ; and 42,235, or over 2 per cent, Animists. Among

the Hindus there are some Dadupanthis (a sect described in the article

on Naraina in the Jaipur State, which is their head-quarters), but their

number was not recorded at the last Census. In addition to the two

subdivisions of the sect mentioned in that article, there is a third which

is said to be peculiar to Jodhpur and is called Gharbari.

Its members

marry and are consequently not recognized in Jaipur as true Dadu-

panthis. Another sect of Hindus deserving of notice is that of the

Bishnois, who number over 37,000, and derive their name from their

creed of twenty-nine (bis+nau) articles. The Bishnois are all Jats by

tribe, and are strict vegetarians, teetotallers, and non-smokers; they

bury their dead sometimes in a sitting posture and almost always at the

threshold of the house or in the adjoining cattle-shed, take neither food

nor water from any other caste, and have their own special priests. The

language mainly spoken throughout the State is Marwarf, the most

important of the four main groups of Rajasthanl.

Among castes and tribes the Jats come first, numbering 220,000, or over 1 1 per cent of the total They are robust and hard-working and the best cultivators in the State, famed for their diligence in improving the land. Next come the Brahmans (192,000, or nearly 10 per cent). The principal divisions are the Srlmalis, the Sanchoras, the Pushkarnas, the Nandwana Borahs, the Chenniyats, the Purohits, and the Paliwals. They are mostly cultivators, but some are priests or money-lenders or in service.

The third most numerous caste is that of the Rajputs

(181,000, or over 9 per cent). They consider any pursuit other than

that of arms or government as derogatory to their dignity, and are con-

sequently indifferent cultivators. The principal Rajput clan is that of

the ruling family, namely Rathor, comprising more than 100 septs, the

chief of which are Mertia, Jodha, Udawat, Champawat, Kampawat,

Karnot, Jaitawat, and Karamsot After the Rajputs come the Mahajans

(171,000, or nearly 9 per cent.). They belong mostly to the Oswal,

Mahesri, Porwal, SaraogI, and Agarwal subdivisions, and are traders

and bankers, some having agencies in the remotest parts of India, while

a few are in State service.

The only other caste exceeding 100,000 is

that of the Balais, or Bhambis (142,000, or over 7 per cent). They

are among the very lowest castes, and are workers in leather, village

drudges, and to a small extent agriculturists. Those who remove the

carcases of dead animals from villages or towns are called Dheds.

Other fairly numerous castes are the Rebans (67,000), breeders of

camels, sheep, and goats; the Malis (55,000), market-gardeners and

agriculturists ; the Chakars or Golas (55,000), the illegitimate offspring

of Rajputs, on whom they attend as hereditary servants ; and lastly the

Kumhars (51,000), potters, brick-burners, village menials, and, to a

small extent, cultivators.

Taking the population as a whole, more than

58 per cent live by the land and about another 3 per cent are partially

agriculturists. Nearly 5 per cent, are engaged in the cotton industry

or as tailors, &c. ; more than 4 per cent, are stock-breeders and dealers,

while commerce and general labour employ over 3 per cent. each.

Christians number 224, of whom in are natives. The United Free Church of Scotland Mission has had a branch at Jodhpur city since 1885.

Agriculture

As already remarked, Jodhpur is, speaking generally, a sandy tract, improving gradually from a mere desert in the west to comparatively fertile lands along the eastern border. The chief natural soils are mattiyali, bhuri ,retli, and magra or tharra. The first is a clayey loam of three kinds, namely kali (black), rati (red), and plli (yellowish), and covers about 18 per cent, of the cultivated area. It does not need frequent manuring, but being stiff requires a good deal of labour; it produces wheat, gram, and cotton, and can be tilled for many years in succession. The second is the most prevalent soil (occupying over 58 per cent, of the cultivated area) and requires but moderate rains.

It has less clay than mattiyali and is brown in colour ; it is easily amenable to the plough, requires manure, and is generally tilled for three or four years and then left fallow for a similar period. The third class of soil (retli) is fine-grained and sandy without any clay, and forms about 19 per cent of the culti- vated area. When found in a depression, it is called dehri, and, as it retains the drainage of the adjacent high-lying land, yields good crops olbajra saidjowdr; but when on hillocks or mounds, it is called Aora, and the sand being coarse-grained, it is a very poor soil requiring frequent rest. Magra is a hard soil containing a considerable quantity of stones and pebbles ; it is found generally near the slopes of hills, and occupies about 4 per cent, of the cultivated area.

The agricultural

methods employed are of the simplest description. For the autumn

crops, ploughing operations begin with the first fall of sufficient rain

(not less than one inch), and the land is ploughed once, twice, or three

times, according to the stiffness of the soil. Either, a camel or a pair

of bullocks is yoked to each plough, but sometimes donkeys or buffaloes

are used. More trouble is taken with the cultivation of the spring

crops. The land is ploughed from five to seven times, is harrowed and

levelled, and more attention is paid to weeding.

In a considerable portion of the State there is practically only one harvest, the khaftf^ or, as it is called here, sawnu ; and the principal crops are bdjra,jowar, motk, til % maize, and cotton. The cultivation of rabiy or unalu crops, such as wheat, barley, gram, and mustard seed, is confined to the fertile portion enclosed within the branches of the Luni river, to the favoured districts along the eastern frontier, and to such other parts as possess wells.

Agricultural statistics are available for

only a portion of the khalsa area (i.e. land paying revenue direct to the

State), measuring nearly 4,320 square miles. Of this area, 1,012 square

miles (or more than 23 per cent.) were cultivated in 1903-4; and the

following were the areas in square miles under the principal crops :

bajra, 430 ,jawar, 151 ; wheat, 81 ; til, 66 ; barley, 23 ; and cotton, 11.

Of the total cultivated area above mentioned, 150 square miles (or

nearly 15 per cent.) were irrigated in 1903-4: namely, m from wells,

12 from canals and tanks, and 27 from other sources. There are, in

khdlsa territory, 22 tanks, the most important of which are the Jaswant

Sagar and Sardar Samand, called after the late and the present chief

respectively. Irrigation is mainly from wells, of which there are 7,355

in the khdlsa area.

The water is raised sometimes by means of the

Persian wheel, and sometimes in leathern buckets. A masonry well

costs from Rs. 300 to Rs. 1,000, and a kachchd well, which will last

many years, from Rs. 150 to Rs. 300. Shallow wells are dug yearly

along the banks of rivers at a cost of Rs. 10 to Rs. 20 each, and the

water is lifted by a contrivance called chdnch y which consists of a

horizontal wooden beam balanced on a vertical post with a heavy

weight at one end and a small leathern bucket or earthen jar at the

other.

The main wealth of the desert land consists of the vast herds of camels, cattle, and sheep which roam over its sandy wastes and thrive admirably in the dry climate. The best riding camels of MarwSr breed come from Sheo in the west and are known as Rama Thalia ; they are said to cover 80 or even 100 miles in a night. Mallani, Phalodi, Shergarh, and Sankra also supply good riding camels, the price of which ranges from Rs. 150 to Rs. 300. The bullocks of Nagaur are famous throughout India; a good pair will sometimes fetch over Rs. 300, but the average price is Rs. 150.

The districts of Sanchor

and Mallani are remarkable for their breed of milch cows and horses.

The latter are noted for their hardiness and ease of pace. The principal

horse and cattle fairs are held at Parbatsar in September and at Tilwara

(near Balatra) in March-

Forests cover an area of about 355 square miles, mostly in the east

and south-east They are managed by a department which was organ-

ized in 1888. There are three zones of vegetation. On the higher

slopes are found sd/ar (Boswellia thurifera), gol ( Odina Wodier),

karayia (Sterculia urens)and golia dhao (Anogeissus latifolia). On

the lower hills and slopes the principal trees are the dhao (Anogeissus

pendula) and sd/ar ; while hugging the valleys and at the foot of the

slopes are dhdk (Butea frondosa,)ber (Zizyphus Jujubd), khair (Acacia

Catechu), dhdman (Gmvia pilosa), &c.

The forests are entirely closed

to camels, sheep, and goats, but cattle are admitted except during the

rains. Right-holders obtain forest produce free or at reduced rates,

and in years of scarcity the forests are thrown open to the public for

grazing, grass-cutting, and the collection of fruits, flowers, &c. The

forest revenue in 1904-5 was about Rs. 31,000, and the expenditure

Rs. 20,000.

The principal mineral found in the State is salt. Its manufacture is

practically a monopoly of the British Government, and is carried on

extensively at the Sambhar Lake, and at Didwana and Pachbhadra.

Marble is mostly obtained from Makrana near the Sambhar Lake,

but an inferior variety is met with at various points in the Aravalli

Hills, chiefly at Sonana near Desuri in the south-east The average

yearly out-turn is about 1,000 tons, and the royalty paid to the Darbar

ranges from Rs. 16,000 to Rs. 20,000. Sandstone is plentiful in many

parts, but varies greatly in texture and in colour. It is quarried in

slabs and blocks, large and small, takes a fine polish, and is very suit-

able for carving and lattice-work, The yearly out-turn is about 6,000

tons. Among minerals of minor importance may be mentioned gypsum,

used as cement throughout the country, and found chiefly near Nagaur;

and fuller's earth, existing in beds 5 to 8 feet below the surface in the

Phalodi district and near Banner, which is largely used as a hair-wash.

Trade and communication

The manufactures are not remarkable from a commercial point of view. Weaving is an important branch of the ordinary village industry, but nothing beyond coarse cotton and woollen cloths is attempted- Parts of the Jodhpur and Godwar dis- tricts are locally famous for their dyeing and printing of cotton fabrics. Turbans for men and scarves for women, dyed and prepared with much labour, together with embroidered silk knotted thread for wearing on the turban, are peculiar to the State. Other manufactures include brass and iron utensils at Jodhpur and Nagaur, ivory-work at Pali and Merta, lacquer-work at Jodhpur, Nagaur, and Bagri (in the Sojat district), marble toys, &c, at Makrana, felt rugs in the Mallani and Merta districts, saddles and bridles at Sojat, and camel- trappings and millstones at Banner. The Darbar has its own ice and aerated water factory, and there are five wool and cotton-presses belong- ing to private individuals.

The chief exports are salt, animals, hides, bones, wool, cotton, oil- seeds, marble, sandstone, and millstones; while the chief imports include wheat, barley, maize, gram, rice, sugar, opium, dry fruits, metals, oil, tobacco, timber, and piece-goods. It is estimated that 80 per cent of the exports and imports are carried by the railway, and the rest by camels, carts, and donkeys, chiefly the former.

The Rajputana-Malwa Railway traverses the south-eastern part of the State, and this section was opened for traffic in 1879-80 ; its length in Jodhpur territory is about 114 miles, and there are 16 stations. A branch of this railway from Sambhar to Kuchawan Road (in the north-east), opened about the same time, has a length of 15 miles with two stations (excluding Sambhar). The State has also a railway of its own, constructed gradually between 1881 and 1900, which forms part of the system known as the Jodhpur-Blkaner Railway.

This line runs

north-west from Marwar Junction, on the Rajputana-Malwa Railway,

to Luni junction, and thence (1) to the western border of the State in

the direction of Hyderabad in Sind, and (2) north to Jodhpur city.

From the latter it runs north-east past Merta Road to Kuchawan Road,

where it again joins the Rajputana-Malwa Railway, and from Merta

Road it runs north-west to Blkaner and Bhatinda. The section within

Jodhpur limits has a length of 455 miles, and the total capital outlay

to the end of 1904 was nearly 122 lakhs. The mean percentage of

net earnings on capital outlay from the commencement of operations

to the end of 1904 has heen 7-90, with a minimum of 3-92 and

a maximum of 11-40. In 1904 the gross working expenses were

7-3 lakhs and the net receipts 9-6 lakhs, yielding a profit of 7-86 per

cent, on the capital outlay.

The total length of metalled roads is about 47 miles and of un- metalled roads 108 miles. All are maintained by the State. The metalled roads are almost entirely in or near the capital, while the principal unmetalled communication is a portion of the old Agra- Ahmadabad road. It was constructed between 1869 and 1875, was originally metalled, and cost nearly 5 lakhs, to which the British Government contributed Rs. 84,000. It runs from near Beawar to Erinpura, and, having been superseded by the railway, is now main- tained merely as a fair-weather communication.

The Darbar adopted Imperial postal unity in 1885-6; and there are now nearly 100 British post offices and five telegraph offices in the State, in addition to the telegraph offices at the numerous railway stations.

The country falls within the area of constant drought, and is liable to frequent famines or years of scarcity. A local proverb tells one to expect ' one lean year in three, one famine year in eight'; and it has proved very true, for since 1792 the State has been visited by seventeen famines. Of those prior to 1868, few details are on record, but the year 1812-13 is described as having been a most calamitous one. The crops failed completely; food-stuffs sold at 3 seers for the rupee, and in places could not be purchased at any price; and the mortality among human beings was appalling. The famine of 1868-9 was one of the severest on record.

There was a little rain in June and July,

1868, but none subsequently in that year; the grain-crops failed and

forage was so scarce in some places that, while wheat was selling at

6, the price of grass was 5 ½ seers per rupee. The import duty on

grain was abolished, and food was distributed at various places by some

of the Ranis, Thakurs, and wealthy inhabitants ; but the Darbar,

beyond placing a lakh of rupees at the disposal of the Public Works

department, did nothing. The highest recorded price of wheat was

3 ½ seers per rupee at Jodhpur city, but even here and at Pali (the two

principal marts) no grain was to be had for days together. Cholera

broke out in 1869 and was followed by a severe type of fever, and it

was estimated that from these causes and from starvation the State

lost one-third of its population.

The mortality among cattle was put at 85 per cent. The next great famine was in 1877-8. The rainfall was only 4 ½ inches ; the kharif crops yielded one-fourth and the rabi one-fifth of the normal out-turn, and there was a severe grass famine. Large numbers emigrated to Gujarat and Malwa with their cattle, and the Darbar arranged to bring the majority back at the public expense, but it was estimated that 20,000 persons and 80,000 head of cattle were lost. This bad season is said to have cost the State about 10 lakhs. The year 189 1-2 was one of triple famine (grain, water, and fodder), the distress being most acute in the western districts. About 200,000 persons emigrated with 662,000 cattle, and only 63 per cent, of the former and 58 percent, of the latter are said to have returned. The Darbar opened numerous relief works and poorhouses ; the railway proved a great boon, and there was much private charity. Direct expenditure exceeded 5 ½ lakhs, while remissions and suspensions of land revenue amounted respectively to about 2-8 and i-6 lakhs.

A

succession of bad seasons, commencing from 1895-6, culminated in

the terrible famine of 1899-1900. At the capital less than half an

inch of rain fell in 1899, chiefly in June, while in two of the western

districts the total fall was only one-seventh of an inch. Emigration

with cattle began in August, but it was long before the people realized

that Malwa, where salvation is usually to be found, was equally

afflicted by drought. Some thousands were brought back by railway

to relief works in Jodhpur at the expense of the Darbar, and thousands

more toiled back by road, after losing their cattle and selling all their

household possessions. Relief works and poorhouses were started on

an extensive scale in the autumn of 1899 and kept open till September,

1900. During this period nearly 30 million units were relieved.

The

total cost to the Darbar exceeded 29 lakhs, and in addition nearly

9 ½ lakhs of land revenue, or about 90 per cent, of the demand, was

remitted. A virulent type of malarial fever which, as in 1869, immedi-

ately followed the famine, claimed many victims. There was no

fodder-crop worthy of the name throughout the State, and for some

time grass was nearly as dear as grain. The mortality among the cattle

was estimated at nearly a million and a half. Since then, the State suf-

fered from scarcity in 1902 in the western districts, and again in 1905.

Administration

For administrative purposes, Jodhpur is divided into twenty-three districts or hukumats (each under an officer called hakim). In Mallani, however, there is, in consequence of its peculiar tenure, size, and recent restoration to the Darbar, an official termed Superintendent, while the north-eastern districts have also a Superintendent to dispose of border cases under the extradition agreement entered into with the Jaipur and Bikaner Darbars.

The State is ordinarily governed by the Maharaja, assisted by the Mahakma khas (a special department consisting of two members) and a consultative Council ; but, during the absence of His Highness, first with the Imperial Cadet Corps and next at Pachmarhl in search of health, the administration has, since 1902, been carried on by the Mahakma khas under the general supervision and control of the Resident.

For the guidance of its judiciary the State has its own codes and laws, which follow generally the similar enactments of British India. There are now 41 Darbar courts and 44 jagirdars courts possessing various powers.

The normal revenue of the State is between 55 and 56 lakhs, and the expenditure about 36 lakhs. The chief sources of revenue are : salt, including treaty payments, royalty, &c, about 16 lakhs; customs, 10 to n lakhs; land (including irrigation), 8 to 9 lakhs; railway, about 8 lakhs (net) ; and tribute from jagfrddrs and succession fees, &c, about 3^ lakhs. The main items of expenditure are : army (including police), about 7f lakhs ; civil establishment, 4 lakhs ; public works (ordinary), 3 to 4 lakhs ; palace and household, about 3 lakhs ; and tribute (including payment for the Erinpura Regiment), nearly i\ lakhs. During the last few years the expenditure has purposely been kept low, in order to extricate the State from its indebtedness ; but now that the financial outlook is brighter, an increased expenditure under various items, such as police, public works, and education, may be expected.

The State had formerly its own silver coinage, one issue being known as Bijai shahi and another as Iktisanda. The Iktlsanda rupee was worth from 10 to 12 British annas, while the value of the Bijai shahi was generally much the same as, and sometimes greater than, that of the British rupee. After 1893 exchange fluctuated greatly till, in 1899, i22f Bijai shahi rupees exchanged for 100 British. The Darbar thereupon resolved to convert its local coins, and the British silver currency has been made the sole legal tender in the State. In 1900 more than 10,000,000 rupees were recoined at the Calcutta mint.

Of the 4,030 villages in the State only 690 are khalsa, or under the direct management of the Darbar, and they occupy about one-seventh of the entire area of the State. The rest of the land is held by jagfr- ddrs, dhumids, and indmdars, or by Brahmans, Charans, or religious and charitable institutions on the sdsan or dohli tenure, or in lieu of pay pasaila )or for maintenance (Jivka), &c, &c. The ordinary jagirdars pay a yearly military cess, supposed to be 8 per cent, of the gross rental value (rekh) of their estates, and have to supply one horse- man for every Rs. 1,000 of rekh.

In the smaller estates they supply

one foot-soldier for every Rs. 500, or one camel sowar for every

Rs. 750. In some cases the jagfrdar, instead of supplying horsemen,

&c, makes a cash payment according to a scale fixed by the Darbar.

Jdgirddrs have also to pay hukmndma or fee on succession, namely

75 per cent, of the annual rental value of their estates ; but, in the case

of a son or grandson succeeding, no cess is levied or service demanded

for that year, while if a more distant relative succeeds the service alone

is excused. The Thakurs of Mallani, holding prior to the Rathor

conquest, pay a fixed sum (faujbat) yearly and have no further

obligations. The bhumias have to perform certain services, such as

protecting their villages, escorting treasure, and guarding officials when

on tour, and some pay a quit-rent called bhum-bdb ; provided these

conditions are satisfied, and they conduct themselves peaceably, their

lands are not resumed.

Inam is a rent-free grant for services rendered ;

it lapses on the failure of lineal descendants of the original grantee,

and is sometimes granted for a single life only. Sdsam and dohli lands

are granted in charity on conditions similar to indm t and cannot be

sold. Jivka is a grant to the younger sons of the chief or of a Th&kur.

After three generations the holder has to pay cess and succession fee,

and supply militia like the ordinary jdgfrddr, and on failure of lineal

descendants of the original grantee the land reverts to the family

of the donor. In the khdlsa area the proprietary right rests with the

Darbar, which deals directly with the ryots. The latter may be

bdpidars ,possessing occupancy rights and paying at favoured rates,

or gair-bdpiddrs, tenants-at-will.

Formerly the land revenue was paid almost entirely in kind. The most prevalent system was that known as lata or batat, by which the produce was collected near the village and duly measured or weighed. The share taken by the Darbar varied from one-fifth to one-half in the case of ' dry,' and from one-sixth to one-third in the case of ' wet ' crops. This mode still prevails in some of the alienated villages, but in the khdlsa area a system of cash rents has been in force since 1894. The first and only regular settlement was made between 1894 and 1896 in 566 of the khdlsa villages (originally for a period of ten years). It is on the ryotwdri system.

The village area is divided into (1) secure,

i.e. irrigated from wells or tanks, where the yearly out-turn varies but

slightly, and remissions of revenue are necessary only in years of dire

famine ; and (2) insecure, or solely dependent on the rainfall. In the

former portion the assessment is fixed, and in the latter it fluctuates

in proportion to the out-turn of the year. The basis of the assessment

was the old batai collections together with certain cesses, and the

gross yield was calculated from the results of crop experiments made

at the time, supplemented by local inquiries. The rates per acre of

wet' land range from Rs. 2-5-6 to Rs. 10 (average, Rs. 2-10-6), while

those for ' dry ' land range from 1 ½ to 12 ½ annas (average, 4 ½ annas).

The State maintains two regiments of Imperial Service Lancers (normal strength 605 per regiment), and a local force consisting of about 600 cavalry (including camel sowars) and 2,400 infantry. The artillery numbers 254 of all ranks, and there are 121 guns of various kinds, of which 75 (namely, 45 field and 30 fort) are said to be service- able. In addition, the irregular militia supplied by the jagirdars mustered 2,019 m I 904-5 : namely, 1,785 mounted men and 234 infantry. The Imperial Service regiments were raised between 1889 and 1893, and are called the Sardar Risala, after the present chief. Their cost in 1904-5, when they were considerably below strength, was about 3-2 lakhs.

The first regiment formed part of the reserve brigade

of the Tlrhh Field Force in 1897-8, and two detachments did well on

convoy duty ; the same regiment was on active service in China in

1 900- 1, was largely represented in the expedition to the Laushan hill

and Chinausai, and was permitted to bear on its colours and appoint-

ments the honorary distinction 'China, 1900.' There are no canton-

ments in the State, but the Darbar contributes a sum of 1-2 lakhs yearly

towards the cost of the 43rd (Erinpura) Regiment (see Erinpura).

Police duties have hitherto been performed by the local force above mentioned; but since August, 1905, a regular police force under an Inspector-General, numbering about 1,500 of all ranks and estimated to cost about 2 ½ lakhs a year, has been formed. In addition, a small force is employed on the Jodhpur-Blkaner Railway.

Besides the Central jail at the capital, there are subsidiary jails at the head-quarters of the several districts, in which persons sentenced to three months' imprisonment or less are confined, and lock-ups for under-trial prisoners at each thdna or police-station.

In the literacy of its population Jodhpur stands second among the twenty States and chiefships of Rajputana, with 5,4 per cent. (10 males and o,3 females) able to read and write. Excluding numerous indi- genous schools, such as Hindu posdls and Musalman maktabs, 4 private institutions maintained by certain castes but aided by the Darbtr, and a Mission girls' school, there were, in 1905, 33 educational institutions kept up by the State, one of which was for girls. The number on the rolls was nearly 2,300 (more than 50 per cent, being Mahajans and Br&hmans, and 1 2 per cent. Musalmans), and the daily average attend- ance during 1904-5 was about 1,740. The most notable institutions are at the capital : namely, the Arts college, the high school, and the Sanskrit school. Save at the small railway school at Merta Road, where a monthly fee of 2 or 4 annas per pupil is taken, education is free throughout the State, and the expenditure exceeds Rs. 44,000 a year.

There are 24 hospitals and 8 dispensaries in the State, which have accommodation for 342 in-patients. In 1904 more than 178,000 cases, including nearly 3,000 in-patients, were treated, and about 7,700 opera- tions were performed. The State expenditure on medical institutions, including allowances to the Residency Surgeon, is approximately Rs. 70,000 yearly.

Vaccination was started about 1866, is compulsory throughout the State, and not unpopular. A staff of 2 superintendents and 22 vacci- nators is maintained, and in 1904-5 they successfully vaccinated 61,000 persons, or nearly 32 per 1,000 of the population.

[C. K. M. Walter, Gazetteer of Marwar and Mallani (1887) ; Rajput- ana Gazetteer •, vol. ii (1879, under revision); Sukhdeo Parshad, The Rathors, their Origin and Growth (Allahabad, 1896); Report on Famine Relief Operations in Marwar during 1896-7 and during 1 899-1900; Report on the Census of Marwar in 1891, vols, i and ii (189 1-4) ; A. Adams, The Western Rajput ana States (1899) ; also Administration Reports of the Marwar State (annually from 1884-5).]