Jogi

This article was written in 1916 when conditions were different. Even in Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

From The Tribes And Castes Of The Central Provinces Of India

By R. V. Russell

Of The Indian Civil Service

Superintendent Of Ethnography, Central Provinces

Assisted By Rai Bahadur Hira Lal, Extra Assistant Commissioner

Macmillan And Co., Limited, London, 1916.

NOTE 1: The 'Central Provinces' have since been renamed Madhya Pradesh.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from the original book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to their correct place.

Contents |

Jogi

Jogi, Yogi

The well-known order of religious mendi- r . The cants and devotees of Siva. The Jogi or Yogi, properly so ^a called, is a follower of the Yoga system of philosophy founded by Patanjali, the main characteristics of which are a belief in the power of man over nature by means of austerities and the occult influences of the will. The idea is that one who has obtained complete control over himself, and entirely subdued all fleshly desires, acquires such potency of mind and will that he can influence the forces of nature at his pleasure.

The Yoga philosophy has indeed so much sub- stratum of truth that a man who has complete control of himself has the strongest will, and hence the most power to influence others, and an exaggerated idea of this power is no doubt fostered by the display of mesmeric control and similar phenomena. The fact that the influence which can be exerted over other human beings through their minds in no way extends to the physical phenomena of inanimate nature is obvious to us, but was by no means so to the uneducated

tion of the senses or

Hindus, who have no clear conceptions of the terms mental and physical, animate and inanimate, nor of the ideas con- noted by them. To them all nature was animate, and all its phenomena the results of the actions of sentient beings, and hence it was not difficult for them to suppose that men could influence the proceedings of such beings. And it is a matter of common knowledge that savage peoples believe their magicians to be capable of producing rain and fine weather, and even of controlling the course of the sun.

1 The Hindu sacred books indeed contain numerous instances of ascetics who by their austerities acquired such powers as to compel the highest gods themselves to obedience. Abstrac- The term Yoga is held to mean unity or communion with God, and the Yogi by virtue of his painful discipline auto- and mental and physical exercises considered himself divine. hypnotism. „ ^& acj ept acquires the knowledge of everything past and future, remote or hidden ; he divines the thoughts of others, gains the strength of an elephant, the courage of a lion, and the swiftness of the wind ; flies into the air, floats in the water, and dives into the earth, contemplates all worlds at one glance and performs many strange things.

" 2 The following excellent instance of the pretensions of the Yogis is given by Professor Oman : 3 " Wolff went also with Mr. Wilson to see one of the celebrated Yogis who was lying in the sun in the street, the nails of whose hands were grown into his cheeks and a bird's nest upon his head. Wolff asked him, ' How can one obtain the knowledge of God?' He replied, 'Do not ask me questions; you may look at me, for I am God.'

"It is certainly not easy at the present day," Professor Oman states,4 " for the western mind to enter into the spirit of the so-called Yoga philosophy ; but the student of religious opinions is aware that in the early centuries of our era the Gnostics, Manichaeans and Neo-Platonists derived their peculiar tenets and practices from the Yoga-vidya of India, and that at a later date the Sufi philosophy of Persia drew its most remarkable ideas from the same source. 5 The 1 This has been fully demonstrated 3 Quoting from Dr. George Smith's by Sir J. G. Frazer in The Golden Life of Dr. Wilson, p. 74. Bough. J i Ibidem, pp. 13-15. 2 Colebrooke's Essays. 6 Weber's Indian Literature, p. 239.

great historian of the Roman Empire refers to the subject in the following passage

- " The Fakirs of India and the monks

of the Oriental Church, were alike persuaded that in total abstraction of the faculties of the mind and body, the pure spirit may ascend to the enjoyment and vision of the Deity. The opinion and practice of the monasteries of Mount Athos will be best represented in the words of an abbot, who flourished in the eleventh century : ' When thou art alone in thy cell,' says the ascetic teacher, ' Shut thy door, and seat thyself in a corner, raise thy mind above all things vain and transitory, recline thy beard and chin on thy breast, turn thine eyes and thy thoughts towards the middle of the belly, the region of the navel, and search the place of the heart, the seat of the soul.

At first all will be dark and comfortless ; but if you persevere day and night, you will feel an ineffable joy ; and no sooner has the soul discovered the place of the heart, than it is involved in a mystic and ethereal light.' This light, the production of a distempered fancy, the creature of an empty stomach and an empty brain, was adored by the Quietists as the pure and perfect essence of God Himself." 1 " Without entering into unnecessary details, many of which are simply disgusting, I shall quote, as samples, a few of the rules of practice required to be followed by the would-be Yogi in order to induce a state of Samadhi— hypnotism or trance—which is the condition or state in which the Yogi is to enjoy the promised privileges of Yoga.

The extracts are from a treatise on the Yoga philosophy by Assistant Surgeon Nobin Chander Pal." J " Place the left foot upon the right thigh, and the right foot upon the left thigh ; hold with the right hand the right great toe and with the left hand the left great toe (the hands coming from behind the back and crossing each other) ; rest the chin on the interclavicular space, and fix the sight on the tip of the nose. " Inspire through the left nostril, fill the stomach with the inspired air by the act of deglutition, suspend the 1 Gibbon's Decline and Fall of'the Roman Empire, chap, lxiii. 2 Republished in the Theosophist.

breath, and expire through the right nostril. Next inspire through the right nostril, swallow the inspired air, suspend the breath, and finally expire through the left nostril. " Be seated in a tranquil posture, and fix your sight on the tip of the nose for the space of ten minutes. " Close the cars with the middle fingers, incline the head a little to the right side and listen with each ear attentively to the sound produced by the other ear, for the space of ten minutes. " Pronounce inaudibly twelve thousand times the mystic syllable Om, and meditate upon it daily after deep inspira- tions. " After a few forcible inspirations swallow the tongue, and thereby suspend the breath and deglutate the saliva for two hours.

" Listen to the sounds within the right ear abstractedly

for two hours, with the left ear.

"Repeat the mystic syllable Om 20,736,000 times in silence and meditate upon it. " Suspend the respiratory movements for the period of twelve days, and you will be in a state of Samadhi." Another account of a similar procedure is given by Buchanan : 1 " Those who pretend to be eminent saints

perform the ceremony called Yoga, described in the Tantras.

In the accomplishment of this, by shutting what are called

the nine passages (dwdra, lit. doors) of the body, the votary

is supposed to distribute the breath into the different parts

of the body, and thus to obtain the beatific vision of various gods.

It is only persons who abstain from the indulgence of concupiscence that can pretend to perform this ceremony, which during the whole time that the breath can be held in the proper place excites an ecstasy equal to whatever woman can bestow on man." 3. Breath- It is clear that the effect of some of the above practices g" t ^rough is designed to produce a state of mind resembling the nostril. hypnotic trance. The Yogis attach much importance to the effect of breathing through one or the other nostril, and this 1 Eastern India, ii. p. 756.

is also the case with Hindus generally, as various rules con- cerning it are prescribed for the daily prayers of Brfihmans. To have both nostrils free and be breathing through them at the same time is not good, and one should not begin any business in this condition. If one is breathing only through the right nostril and the left is closed, the condition is pro- pitious for the following actions : To eat and drink, as diges- tion will be quick ; to fight ; to bathe ; to study and read

- to ride on a horse ; to work at one's livelihood.

A sick man should take medicine when he is breathing through his right nostril. To be breathing only through the left nostril is propitious for the following undertakings : To lay the foundations of a house and to take up residence in a new house ; to put on new clothes ; to sow seed ; to do service or found a village ; to make any purchase. The Jogis prac- tise the art of breathing in this manner by stopping up their right and left nostril alternately with cotton-wool and breath- ing only through the other.

If a man comes to a Brahman to ask him whether some business or undertaking will succeed, the Brahman breathes through his nostrils on to his hand ; if the breath comes through the right nostril the omen is favourable and the answer yes ; if through the left nostril the omen is unfavourable and the answer no. The following account of the austerities of the Jogis 4. Sdf- during the Mughal period is given by Bernier : ' " Among the vast number and endless variety of Fakirs or Dervishes, and holy men or Gentile hypocrites of the Indies, many live in a sort of convent, governed by superiors, where vows of chastity, poverty, and submission are made. So strange is the life led by these votaries that I doubt whether my description of it will be credited. I allude particularly to the people called 'Jogis,' a name which signifies 'United to God.' Numbers are seen day and night, seated or lying on ashes, entirely naked ; frequently under the large trees near talabs or tanks of water, or in the galleries round the Deuras or idol temples. Some have hair hanging down to the calf of the leg, twisted and entangled into knots, like the coats of our shaggy dogs. I have seen several who hold one, and some who hold both arms perpetually lifted above the head, 1 Travels in the Mughal Empire, Constable's edilion, p. 316. torture of the Jogis.

the nails of their hands being twisted and longer than half my little finger, with which I measured them. Their arms are as small and thin as the arms of persons who die in a decline, because in so forced and unnatural a position they receive not sufficient nourishment, nor can they be lowered so as to supply the mouth with food, the muscles having become contracted, and the articulations dry and stiff. Novices wait upon these fanatics and pay them the utmost respect, as persons endowed with extraordinary sanctity. No fury in the infernal regions can be conceived more horrible than the Jogis, with their naked and black skin, long hair, spindle arms, long twisted nails, and fixed in the posture which I have mentioned.

" I have often met, generally in the territory of some Raja, bands of these naked Fakirs, hideous to behold. Some have their arms lifted up in the manner just described ; the frightful hair of others either hung loosely or was tied and twisted round their heads ; some carried a club like the Hercules, others had a dry and rough tiger-skin thrown over their shoulders.

In this trim I have seen them shamelessly walk stark naked through a large town, men, women, and girls looking at them without any more emotion than may be created when a hermit passes through our streets. Females would often bring them alms with much devotion, doubtless believing that they were holy personages, more chaste and discreet than other men. " Several of these Fakirs undertake long pilgrimages not only naked but laden with heavy iron chains, such as are put about the legs of elephants.

I have seen others who, in con- sequence of a particular vow, stood upright during seven or eight days without once sitting or lying down, and without any other support than might be afforded by leaning forward against a cord for a few hours in the night ; their legs in the meantime were swollen to the size of their thighs. Others, again, I have observed standing steadily, whole hours together, upon their hands, the head down and the feet in the air. I might proceed to enumerate various other posi- tions in which these unhappy men place their body, many of them so difficult and painful that they could not be imitated by our tumblers ; and all this, let it be recollected,

is performed from an assumed feeling of piety, of which there is not so much as the shadow in any part of the Indies." The forest ascetics were credited with prophetic powers, 5. Resort and were resorted to by Hindu princes to obtain omens and ^^.^ ' oracles on the brink of any important undertaking. This custom is noticed by Colonel Tod in the following passage describing the foundation of Jodhpur : x " Like the Druids of the cells, the vana-perist Jogis, from the glades of the forest {yanct) or recess in the rocks (gopha), issue their oracles to those whom chance or design may conduct to their solitary dwellings.

It is not surprising that the mandates of such beings prove compulsory on the superstitious Rajput ; we do not mean those squalid ascetics who wander about India and are objects disgusting to the eye, but the genuine Jogi, he who, as the term imports, mortifies the flesh, till the wants of humanity are restricted merely to what suffices to unite matter with spirit, who had studied and comprehended the mystic works and pored over the systems of philosophy, until the full influence of Maia (illusion) has perhaps un- settled his understanding ; or whom the rules of his sect have condemned to penance and solitude ; a penance so severe that we remain astonished at the perversity of reason which can submit to it.

We have seen one of these objects, self- condemned never to lie down during forty years, and there remained but three to complete the term. He had travelled much, was intelligent and learned, but, far from having contracted the moroseness of the recluse, there was a benignity of mien and a suavity and simplicity of manner in him quite enchanting. He talked of his penance with no vainglory and of its approaching term without any sensation. The resting position of this Druid (vana-perisC) was by means of a rope suspended from the bough of a tree in the manner of a swing, having a cross-bar, on which he reclined. The first years of this penance, he says, were dreadfully painful ; swollen limbs affected him to that degree that he expected death, but this impression had long since worn off. To these, the Druids of India, the prince and the chieftain would resort for instruction. Such was the ascetic who re-

commended Joda to erect his castle of Jodhpur on the ' Hill of Strife' (Jodaglr), a projecting elevation of the same range on which Mundore was placed, and about four miles south of it." 6. Divisions About i 5,ooo Jogis were returned from the Central Pro- of the vinces in 191 I. They are said to be divided into twelve Panths or orders, each of which venerates one of the twelve disciples of Gorakhnath.

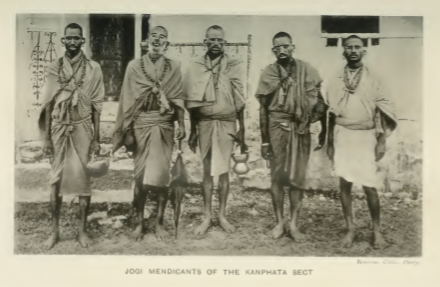

But, as a rule, they do not know the names of the Panths. Their main divisions are the Kanphata and Aughar Jogis. The Kanphatas,1 as the name denotes, pierce their ears and wear in them large rings {inuudra), generally of wood, stone or glass ; the ears of a novice are pierced by the Guru, who gets a fee of Rs. 1-4. The earring must thereafter always be worn, and should it be broken must be replaced temporarily by a model in cloth before food is taken. If after the ring has been inserted the ear tears apart, they say that the man has become useless, and in former times he was buried alive. Now he is put out of caste, and no tomb is erected over him when he dies.

It is said that a man cannot become a Kanphata all at once, but must first serve an apprenticeship of twelve years as an Aughar, and then if his Guru is satisfied he will be initiated as a Kanphata. The elect among the Kanphatas are known as Darshani. These do not go about begging, but remain in the forest in a cave or other abode, and the other Jogis go there and pay their respects ; this is called darshan, the term used for visiting a temple and worshipping the idol. These men only have cooked food when their disciples bring it to them, otherwise they live on fruits and roots. The Aughars do not pierce their ears, but have a string of black sheep's wool round the neck to which is suspended a wooden whistle called nadh ; this is blown morning and evening and before meals.

2 The names of the Kanphatas end in Nath and those of the Aughars in Das. 7. Hair When a novice is initiated all the hair of his head is clothes shaved, including the scalp-lock. If the Ganges is at hand the Guru throws the hair into the Ganges, giving a great feast to celebrate the occasion ; otherwise he keeps the hair in his wallet until he and his disciple reach the Ganges and 1 Maclagan, /.c p. 115. 2 Ibidem, I.e.

then throws it into the river and gives the feast. After this the Jogi lets all his hair grow until he comes to some great shrine, when he shaves it off clean and gives it as an offering to the god. The Jogis wear clothes coloured with red ochre like the Jangams, Sanniasis and all the Sivite orders. The reddish colour perhaps symbolises blood and may denote that the wearers still sacrifice flesh and consume it.

The Vaish- navite orders usually wear white clothes, and hence the Jogis call themselves Lai Padris (red priests), and they call the Vaishnava mendicants Sita Padris, apparently because Sita is the consort of Rama, the incarnation of Vishnu. When a Jogi is initiated the Guru gives him a single bead of rudraksha wood which he wears on a string round his neck. He is not branded, but afterwards, if he visits the temple of Dwarka in Gujarat, he is branded with the mark of the conch-shell on the arm ; or if he goes on pilgrimage to the shrine of Badri-Narayan in the Himalayas he is branded on the chest. Copper bangles are brought from Badri-Narayan and iron ones from the shrine of Kedarnath.

A necklace of small white stones, like juari-seeds, is obtained from the temple of Hinglaj in the territories of the Jam of Lasbela in Beluchistan. During his twelve years' period as a Brahmachari or acolyte, a Jogi will make either one or three parikramas of the Nerbudda ; that is, he walks from the mouth at Broach to the source at Amarkantak on one side of the river and back again on the other side, the journey usually occupying about three years.

During each journey he lets his hair grow and at the end of it makes an offering of all except the choti or scalp-lock to the river. Even as a full Jogi he still retains the scalp- lock, and this is not finally shaved off until he turns into a Sanniasi or forest recluse. Other Jogis, however, do not merely keep the scalp-lock but let their hair grow, plaiting it with ropes of black wool over their heads into what is called the jata, that is an imitation of Siva's matted locks. 1 The Jogis are buried sitting cross-legged with the face 8. Burial, to the north in a tomb which has a recess like those of Muhammadans. A gourd full of milk and some bread in a wallet, a crutch and one or two earthen vessels are placed in

the grave for the sustenance of the soul.

Salt is put on the body and a ball of wheat-flour is laid on the breast of the corpse and then deposited on the top of the grave. 9 . The Jogis worship Siva, and their principal festival is Festivals. ^e Shivratri, when they stay awake all night and sing songs in honour of Gorakhnath, the founder of their order. On the Nag-Panchmi day they venerate the cobra and they take about snakes and exhibit them. 10. Caste A large proportion of the Jogis have now developed j Ub ". into a caste, and these marry and have families. They are divisions. J J divided into subcastes according to the different professions they have adopted. Thus the Barwa or Garpagari Jogis ward off hailstorms from the standing crops ; the Manihari are pedlars and travel about to bazars selling various small articles ; the Rltha Bikanath prepare and sell soap-nut for washing clothes ; the Patbina make hempen thread and gunny - bags for carrying grain on bullocks ; and the Ladaimar hunt jackals and sell and eat their flesh.

These Jogis rank as a low Hindu caste of the menial group. No good Hindu caste will take food or water from them, while they will accept cooked food from members of any caste of respectable position, as Kurmis, Kunbis or Malis. A person belonging to any such caste can also be admitted into the Jogi community.

Their social customs resemble those of the cultivating castes of the locality. They permit widow- marriage and divorce and employ Brahmans for their cere- monies, with the exception of the Kanphatas, who have priests of their own order. 11. Beg- Begging is the traditional occupation of the Jogis, but glng ' they have now adopted many others. The Kanphatas beg and sell a woollen string amulet (ganda), which is put round the necks of children to protect them from the evil eye. They beg only from Hindus and use the cry ' Alakh,' ' The invisible one.'

l The Nandia Jogis lead about with them a deformed ox, an animal with five legs or some other mal- formation. He is decorated with ochre-coloured rags and cowrie shells. They call him Nandi or the bull on which Mahadeo rides, and receive gifts of grain from pious Hindus, half of which they put into their wallet and give the other

1 Crooke's Tribes and Castes, ait. Kanphata.

ii OTHER OCCUPATIONS—SWINDLING PRACTICES 253

half to the animal. They usually carry on a more profitable business than other classes of beggars. The ox is trained to give a blessing to the benevolent by shaking its head and raising its leg when its master receives a gift.1

Some of the Jogis of this class carry about with them a brush of peacock's feathers which they wave over the heads of children afflicted with the evil eye or of sick persons, muttering texts. This performance is known as jharna (sweeping), and is the commonest method of casting out evil spirits. Many Jogis have also adopted secular occupations, as 12. other has already been seen. Of these the principal are the °jo C n u s pa' Manihari Jogis or pedlars, who retail small hand-mirrors, spangles, dyeing-powders, coral beads and imitation jewellery, pens, pencils, and other small articles of stationery. They also bring pearls and coral from Bombay and sell them in the villages.

The Garpagaris, who protect the crops from hailstorms, have now become a distinct caste and are the subject of a separate article. Others make a living by juggling and conjuring, and in Saugor some Jogis perform the three-card trick in the village markets, employing a con- federate who advises customers to pick out the wrong card. They also play the English game of Sandown, which is known as ' Animur,' from the practice of calling out ' Any more ' as a warning to backers to place their money on the board before beginning to turn the fish. These people also deal in ornaments of base metal and 13. Swind- practise other swindles. One of their tricks is to drop a p"fctices ring or ornament of counterfeit gold on the road. Then they watch until a stranger picks it up and one of them goes up to him and says,

" I saw you pick up that gold ring, it belongs to so-and-so, but if you will make it worth my while I will say nothing about it." The finder is thus often deluded into giving him some hush-money and the Jogis decamp with this, having incurred no risk in connection with the spurious metal. They also pretend to be able to con- vert silver and other metals into gold.

They ingratiate themselves with the women, sometimes of a number of households in one village or town, giving at first small quan- tities of gold in exchange for silver, and binding them to 1 Crooke's Tribes and Castes, art. Jogi.

secrecy.

Then each is told to give them all the ornaments which she desires to be converted on the same night, and having collected as much as possible from their dupes the Jogis make off before morning. A very favourite device some years back was to personate some missing member of a family who had gone on a pilgrimage. Up to within a comparatively recent period a large proportion of the pilgrims who set out annually from all over India to visit the famous shrines at Benares, Jagannath and other places perished by the way from privation or disease, or were robbed and mur- dered, and never heard of again by their families.

Many households in every town and village were thus in the position of having an absent member of whose fate they were uncertain. Taking advantage of this, and having obtained all the information he could pick up among the neighbours, the Jogi would suddenly appear in the character of the returned wanderer, and was often successful in keeping up the imposture for years. 1

and there are various sayings about him: 2 Jogi Jogi laren, khopron ka dam, or ' When Jogis fight skulls are smashed,' that is, the skulls which some of them use as begging-cups, not their own skulls, and with the implication that they have nothing else to break ; Jogijitgatjani nahhi, kapre range, to kya hua, ' If the Jogi does not know his magic, what is the use of his dyeing his clothes ? ' Jogi ka larka kfielega, to sdnp se, or, ' If a snake-charmer's son plays, he plays with a snake.' 1 Sleeman, Report on the Badkaks, Temple and Fallon's Hindustani Pro- PP- 332, 333- verbs. 2 These proverbs are taken from

This singular race, found all over Eastern Bengal, is more numerous in Tipperah and Noakhally than Dacca, being everywhere reviled by the Hindus, without any satisfactory reason. The only grounds given by natives for abusing and ill-treating Jogis are that the starch of boiled rice (Mar) is used by them in weaving, while the Tanti use parched rice starch (Kai), and that they bury their dead.

In Bengal three different varieties of Jogi are met with, namely�

Jogi, Bengali weavers, Jat Jogi, Hindustani snake charmers, Sannyasi Jogi, religious mendicants.

Jogi, or Yogi, literally means one who practices the Jog, i.e. religious abstraction, or in a lower sense a pretender to superhuman faculties, while the designation is popularly given to any naked Hindu devotee.

In the census returns, the Jogi and Patwa are classified as one and the same, but in Dacca, the latter is always the name of a Muhammadan trade. The weaver Jogi caste in Bengal is computed to include 426,543 individuals, 306,847, or 71 per cent. of the whole number, being distributed throughout the nine eastern districts. Like many outcast races, the Jogi has been driven into the outlying tracts of the province, and at the present day are massed in Silhet (82,038), Tipperah (66,812), Mymensingh (39,644), Noakhally (33,038), and Chittagong (32,314). In Dacca they only muster 16,410 persons.

Until the last few years the Bengali Jogis were all weavers, but now the cloth (Dhoti and Gamcha) manufactured by them is gradually being displaced by English piece goods, and the Jogi finds it difficult to earn a livelihood by weaving. A few who took to agriculture being outcasted, formed a new subdivision, called Halwah Jogis. In Tipperah the burning of lime has been adopted as an occupation by some, but they, too, have been excommunicated. Others, again, take service under Government, as work as goldsmiths. Recently a shudder ran through the Hindu community when a Jogi was elevated to the bench, but many have already outlived this prejudice, and, except among the upper strata of society, no objections are now raised. The Jogi has peculiar difficulties in having his children educated, as no other boy will live with his son, who is consequently obliged to hire lodgings for himself, and engage servants of his own. The race, however, is ambitious, and recognises the value of education, but being poor, the higher branches of learning are beyond their reach.

The Jogi uses a much more cumbrous loom than either the Tanti or Julaha, but employs the same comb, or "Shanah," while his shuttle, "Nail,"1 is peculiar to himself. The women are as expert weavers as the men, the preparation of the warp being exclusively done by them.

Jogis are a contented people, laughing at the prejudices of their neighbours. When they enter the house of any of the clean castes, a very rare occurrence, all cooked food, and any drinking water in the room, are regarded as polluted, and thrown away, but, strange to say, the Sudra barber and washerman work for them. The Jogi, too, is intolerant, eating food cooked by a Srotriya Brahman, but not that prepared by any Patit, or caste, Brahman, or by a Sudra, however pure. The Sannyasi Jogi eats with the weaving Jogi, but a Bairagi will only touch food given by the Adhikari. Furthermore, the Ekadasi Jogi will eat with the Sannyasi if he is a Brahman observing the Sraddha on the eleventh day.

In the burial of their dead all Jogis observe the same ceremonies. The grave (Samadhi, or Ahsan), dug in any vacant spot, is circular, about eight feet deep, and at the bottom a niche is cut for the reception of the corpse. The body, after being washed with water from seven earthen jars, is wrapped in new cloth, the lips being touched with fire to distinguish the funeral from that of a Muhammadan. A necklace made of the Tulasi plant is placed around the neck, and in the right hand a rosary (Japa). The right forearm, with the thumb inverted, is placed across the chest, while the left, with the thumb in a similar position, rests on the lap, the legs being crossed as in statues of Buddha. Over the left shoulder is hung a cloth bag with four strings, in which four cowries are put. The body being lowered into the grave, and placed in the niche with the face towards the north-east, the grave is filled in, and the relatives deposit on the top an earthen platter with balls of rice (Pinda), plantains, sugar, Ghi, and betel-nuts, as well as a "Huqqa" with its "Chilam" (bowl), a small quantity of tobacco, and a charcoal ball. Finally, from three to seven cowries are scattered on the ground as compensation to "Visa-mati" for the piece of earth occupied by the corpse. Women are interred in the exact same way as men.

The bag with its four cowries, and the position of the body are noteworthy. With the cowries the spirit pays the Charon who ferries it across the Vaitarani river, the Hindu Styx; while the body is made to face the north-east because in that corner of the world lies Kailasa, the Paradise of Siv.

1 Sanskrit Nala, a tube, a shuttle.

The one title common to all the Jogi tribe is Nath, or lord.

The majority worship Mahadeo, or Siv, but a few Vaishnavas are found among them.

Although all Jogis observe the funeral ceremonies just mentioned, they have separated into two great divisions, the Masya, the more numerous in Dacca, who perform the Sraddha thirty days (Masa) after death; and the Ekadasi, who celebrate it after eleven (Ekadasan) days. The former abound in the southern parts of Bikrampur, Tipperah, and Noakhally, the latter in the north of Bikrampur, and throughout the Dacca district generally. No intermarriages take place between them, and each refuses to taste food cooked by the other, although they drink from each other's water vesssels.

1.Masya Jogis

They are the more interesting of the two, having adhered more strictly to the customs of their ancestors than the Ekadasi The following account of their origin is given: In the Vrihad Yogini Tantra, their chief religious work, it is written that to Mahadeo were born eight passionless beings (Siddhas), who practised asceticisms, and passed their lives in religious abstraction. Their arrogance and pride, however, offended Mahadeo, who assuming his illusive power, created eight female energies, or Yoginis, and sent them to tempt the Siddhas. It was soon apparent that their virtue was not so impregnable as they boasted, and the issue of their amours were the ancestors of the modern Masya Jogis.

Another account is that a Sannyasi Avadhuta, or scholar, of Benares, who was an incarnation of Siv, had two sons, the elder by a Brahman woman, becoming the progenitor of the Ekadasi Jogis, the younger by a Vaisya woman of the Masya; but it is probable that this legend has been invented to account for the fact that the two divisions perform the obsequial rites at different dates.

The Masya Jogis have no Brahmans who minister to them, but a spiritual leader, Adhikari, elected by the Purohits, is invested with a cord, and styled Brahman. In Tipperah and Noakhally the cord is still worn, but in Dacca of late years it has been discarded. The Adhikari of the Masya Jogis in Dacca is Mathura Ramana, of Bidgaon, in Bikrampur, a very illiterate man, who can with difficulty read and write Bengali. The post has been hereditary in his family for eight generations, and nowadays it is only in default of heirs that an election is held. It is a curious circumstance that the Adhikari bestows the Mantra on the Brahmans of the Ekadasi, and occasionally on Sannyasi Jogis, although neither acknowledge any subjection to him. The Adhikari has no religious duties to perform, as each household employs a Purohit to minister at its religious ceremonies. The Purohit is always a Jogi, inducted by the Adhikari, and subordinate to him. He is often a relative, or marries a daughter of his master. The Adhikari, again, has his Purohit, without whose ministration neither he nor any member of his family can marry or be buried.

The great festival of tthe Masya Jogis is the Sivaratri, held on the fourteenth of the waning moon in Magh (January-February); but they observe many of the other Hindu festivals, such as the Janmashtami, and offer sacrifices beneath the "Bat" tree to the village goddess, Siddhesvari.

In all religious services they use a twig of the Udumbara, or Jagya dumur (Ficus glomerata), and regard with special reverence the Tulasi, Bat, Pipal, and "Tamala" (Diospyrus cordifolia).

They have Sthans, or residencies, at Brindaban, Mathura, and Gokula, but their chief places of pilgrimage are Benares, Gaya, and Sitakhund in Chittagong.

2.Ekadasi Jogis== They possess a Sanskrit work called Vriddha Satatapiya, in which the Muni Satatapa relates how the divine Rishi Narada was informed by Brahma that near Kasi resided many Brahman and Vaisya widows, living by the manufacture of thread, who had given birth to sons and daughters the offspring of Avadhutas, or pupils of Nathas, or ascetics. The Rishi was further directed to proceed to Kasi, and, in consultation with the Avadhutas, to decide what the caste of these children should be. After much deliberation it was determined that the offspring of the Avadhutas and Brahman widows should belong to the Siva gotra; while the issue of the Vaisya widows should form a class called Nath, the former like the Brahmans being impure for eleven days, the latter like the Vaisya for thirty days. Both classes were required to read six Vedas, to worship their Matris, or female ancestors, at weddings to perform, each household for itself, the Nandi Sraddha in the name of their forefathers, and to wear the sacred cord.

It was farther enacted that the dead should be buried, the lips of the corpse being touched with fire by the son or grandson. It is from these Brahman widows that the modern Ekadasi Jogis claim to be descended, and being of that lineage, mourn for only eleven days, although they have never assumed the Brahmanical cord.

The Ekadasi have Brahmans of their own, called "Varna-Sarman," and addressed as Mahatama, who trace their origin from the issue of a Srotriya Brahman and a Jogi woman. In Bikrampur alone it is estimated there are at least a hundred of these Jogi Brahmans.

The majority of this division of Jogis are worshippers of Krishna, but a few who follow the Sakta ritual are to be met with. The Gosains of Nityananda admit Jogis into their communion, but those of Advayananda will not.

All Jogis in Eastern Bengal regard the family of Dalal Bazar, in the Noakhally district, as the head of their race, and very proud they are of the distinction which was conferred on that house. In the middle of last century Brijo Ballabh Rai, a Jogi, was Dalal, or broker, his brother Radha Ballabh Rai being Jachandar, or appraiser, of the English factory of Char Pata, on the Meghna. The son of the former developed the trade in Baftah cloth to so great an extent that the Company in 1765 bestowed on him the title and rank of a rajah, presenting him at the same time with a Lakhiraj, or rent free, estate. His grandson still enjoys the property, being respected not only by the Jogis throughout Eastern Bengal, but by all who know him and his family.

The mourning dress of the Jogis is a cotton garment called "Jala Kaccha," literally netted end, manufactured by them, and identical with that worn by other Hindus between the death of a relative and the Sraddha. In a corner of this raiment the Jogi ties a piece of iron, suspending it over his shoulder. On the eleventh day, when the funeral obsequies are about to be performed, the barber, cutting off the iron, gives it to the wearer, who throws it into water, then bathes, offers the Pinda to the manes of the deceased, and returns home.

The Jogi Brahmans are, with few exceptions, illiterate, but a few gain a livelihood as Pathaks, or readers of the epic poems. Jogis are the Mahants of the Kapila Muni shrine in the Sunderbuns, and officiate at the Varuni festival in Phalgun.1

All Jogis believe that good spirits are at death absorbed into the Deity, while the bad reappear on earth in the form of some unclean animal; but women, however exemplary they may have been in this world, are not cheered by any assurance of a future state, it being believed that death is for them annihilation.

Who, then, are the Jogis? Buchanan thought it probable that they were either the priesthood of the country during the reign of the dynasty to which Gopi-Chandra2 belonged, or Sudras dedicated to a religious life, but degraded by the great Saiva reformer Sankara Acharya,1 and that they came with the Pal Rajas from western India. In Rangpur he found the Jogis living by singing an interminable cyclic song in honour of Gopi-Chandra. This is all the information collected by that shrewd and trustworthy observer, and since the beginning of the century no fresh facts have been added.

After repeated interviews with the Adhikari and Jogi Brahmans their history is still uncertain. A tradition, however, survives in Bikrampur, that their ancestors were Brahmans, who, forgetting the Gayatri, or sacred verses, were degraded.

1 "J.A.S. of Bengal," vol. xxxis, 238.

2 Ibid., vol iii, 534.