Kāppiliyan

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Kāppiliyan

The Kāppiliyans, or Karumpuraththāls, as they are sometimes called, are Canarese-speaking farmers, who are found chiefly in Madura and Tinnevelly. It is noted, in the Manual of the Madura district, that “a few of the original Poligars were Canarese; and it is to be presumed that the Kāppiliyans immigrated under their auspices. They are a decent and respectable class of farmers. Their most common agnomen is Koundan (or Kavandan).” Some Kāppiliyans say that they came south six or seven generations ago, along with the Urumikkārans, from the banks of the Tungabhadra river, because the Tottiyans tried to ravish their women. According to another tradition, similar to that current among the Tottiyans, “the caste was oppressed by the Musalmans of the north, fled across the Tungabhadra, and was saved by two pongu (Pongamia glabra) trees bridging an unfordable stream, which blocked their escape. They travelled, says the legend, through Mysore to Conjeeveram, thence to Coimbatore, and thence to the Madura district. The stay at Conjeeveram is always emphasised, and is supported by the fact that the caste has shrines dedicated to Kānchi Varadarāja Perumāl.”

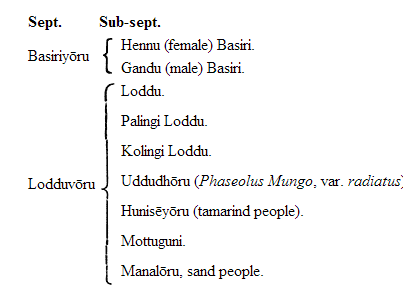

The Kāppiliyans are one of the nine Kambalam castes, who are so called because, at their caste council meetings, a kambli (blanket) is spread, on which is placed a kalasam (brass vessel) filled with water, and decorated with flowers. Its mouth is closed by mango leaves and a cocoanut. According to the Gazetteer of the Madura district, they are “split into two endogamous sub-divisions, namely the Dharmakattu, so called because, out of charity, they allow widows to marry one more husband, and the Mūnukattu, who permit a woman to have three husbands in succession.” They are also said to recognise, among themselves, four sub-divisions, Vokkiliyan (cultivator), Mūru Balayanōru (three bangle people), Bottu Kattōru (bottu tying people), Vokkulothōru, to the last of which the following notes mainly refer. They have a large number of exogamous septs, which are further divided into exogamous sub-septs, of which the following are examples:—

One exogamous sept is called Ānē (elephant), and as names of sub-septs, named after animate or inanimate objects, I may mention Hatti (hamlet), Aranē (lizard) and Puli (tiger). The affairs of the caste are regulated by a headman called Gauda, assisted by the Saundari. In some places, the assistance of a Pallan or Maravan called Jādipillai, is sought.

Marriage is, as a rule, adult, and the common emblem of married life—the tāli or bottu—is dispensed with. On the first day of the marriage ceremonies, the bride and bridegroom are conducted, towards evening, to the houses of their maternal uncles. There the nalagu ceremony, or smearing the body with Phaseolus Mungo, sandal and turmeric paste, is performed, and the uncles place toe-rings on the feet of the contracting couple. On the following day, the bride’s price is paid, and betel is distributed, in the presence of a Kummara, Urumikkāran, and washerman, to the villagers in a special order of precedence. On the third day, the bridegroom goes in procession to the house of the bride, and their fingers are linked together by the maternal uncle or uncles. For this reason, the day is called Kai Kudukāhodina, or hand-locking day.

It is noted, in the Gazetteer of the Madura district, that “the binding portions of the marriage ceremony are the donning by the bride of a turmeric-coloured cloth sent her by bridegroom, and of black glass bangles (unmarried girls may only wear bangles made of lac), and the linking of the couple’s little fingers. A man’s right to marry his paternal aunt’s daughter is so rigorously insisted upon that, as among the Tottiyans, ill-assorted matches are common. A woman, whose husband is too young to fulfil the duties of his position, is allowed to consort with his near relations, and the children so begotten are treated as his. [It is said that a woman does not suffer in reputation, if she cohabits with her brothers-in-law.] Adultery outside the caste is punished by expulsion, and, to show that the woman is thenceforward as good as dead, funeral ceremonies are solemnly performed to some trinket of hers, and this is afterwards burnt.”

At the first menstrual period, a girl remains under pollution for thirteen days, in a corner of the house or outside it in the village common land (mandai). If she remains within, her maternal uncle makes a screen, and, if outside, a temporary hut, and, in return for his services, receives a hearty meal. On the thirteenth day the girl bathes in a tank (pond), and, as she enters the house, has to pass over a pestle and a cake. Near the entrance, some food is placed, which a dog is allowed to eat. While so doing, it receives a severe beating. The more noise it makes, the better is the omen for a large family of children. If the poor brute does not howl, it is supposed that the girl will bear no children. A cotton thread, dyed with turmeric, is tied round her neck by a married woman, and, if she herself is married, she puts on glass bangles. The hut is burnt down and the pots she used are broken to atoms. The caste deities are said to be Lakkamma and Vīra Lakkamma, but they also worship other deities, such as Chenrāya, Thimmappa, and Siranga Perumal. Certain septs seem to have particular deities, whom they worship. Thus Thimmarāya is reverenced by the Dasiriyōru, and Malamma by the Hattiyōru.

The dead are as a rule cremated, but children, those who have died of cholera, and pregnant women, are buried. In the case of the last, the child is, before burial, removed from the mother’s body. The funeral ceremonies are carried out very much on the lines of those of the Tottiyans. Fire is carried to the burning ground by a Chakkiliyan. On the last day of the death ceremonies (karmāndiram) cooked food, fruits of Solanum xanthocarpum, and leaves of Leucas aspera are placed on a tray, by the side of which a bit of a culm of Saccharum arundinaceum, with leaves of Cynodon Dactylon twined round it, is deposited. The tray is taken to a stream, on the bank of which an effigy is made, to which the various articles are offered. A small quantity thereof is placed on arka (Calotropis gigantea) leaves, to be eaten by crows. On the return journey to the house, three men, the brother-in-law or father-in-law of the deceased, and two sapindas (agnates) stand in a row at a certain spot. A cloth is stretched before them as a screen, over which they place their right hands. These a washerman touches thrice with Cynodon leaves dipped in milk, cow’s urine, and turmeric water. The washerman then washes the hands with water. All the agnates place new turbans on their heads, and go back in procession to the village, accompanied by a Urimikkāran and washerman, who must be present throughout the ceremony.

For the following note on the Kāppiliyans of the Kambam valley, in the Madura district, I am indebted to Mr. C. Hayavadana Rao. According to a tradition which is current among them, they migrated from their original home in search of new grazing ground for their cattle. The herd, which they brought with them, still lives in its descendants in the valley, which are small, active animals, well known for their trotting powers. It is about a hundred and fifty strong, and is called dēvaru āvu in Canarese, and thambirān mādu in Tamil, both meaning the sacred herd. The cows are never milked, and their calves, when they grow up, are not used for any purpose, except breeding. When the cattle die, they are buried deep in the ground, and not handed over to Chakkiliyans (leather-workers). One of the bulls goes by the name of pattada āvu, or the king bull. It is selected from the herd by a quaint ceremonial.

On an auspicious day, the castemen assemble, and offer incense, camphor, cocoanuts, plantains, and betel to the herd. Meanwhile, a bundle of sugar-cane is placed in front thereof, and the spectators eagerly watch to see which of the bulls will reach it first. The animal which does so is caught hold of, daubed with turmeric, and decorated with flowers, and installed as the king bull. It is styled Nanda Gōpāla, or Venugōpālaswāmi, after Krishna, the divine cattle-grazer, and is an object of adoration by the caste. To meet the expenses of the ceremony, which amount to about two hundred rupees, a subscription is raised among them. The king bull has a special attendant, or driver, whose duties are to graze and worship it. He belongs to the Māragala section of the Endār sub-division of the caste. When he dies, a successor is appointed in the following manner. Before the assembled castemen, pūja (worship) is offered to the sacred herd, and a young boy, “upon whom the god comes,” points out a man from among the Māragalas, who becomes the next driver.

He enjoys the inams, and is the custodian of the jewels presented to the king bull in former days, and of the copper plates, whereon grants made in its name are engraved. As many as nine of these copper grants were entrusted to the keeping of a youthful driver, about sixteen years old, in 1905. Most of them record grants from unknown kings. One Ponnum Pāndyan, a king of Gudalūr, is recorded as having made grants of land, and other presents to the bull. Others record gifts of land from Ballāla Rāya and Rāma Rāyar. Only the names of the years are recorded. None of the plates contain the saka dates. Before the annual migration of the herd to the hills during the summer, a ceremony is carried out, to determine whether the king bull is in favour of its going. Two plates, one containing milk, and the other sugar, are placed before the herd. Unless, or until the bull has come up to them, and gone back, the migration does not take place. The driver, or some one deputed to represent him, goes with the herd, which is accompanied by most of the cattle of the neighbouring villages. The driver is said to carry a pot of fresh-drawn milk within a kāvadi (shrine).

On the day on which the return journey to the valley is commenced, the pot is opened, and the milk is said to be found in a hardened state. A slice thereof is cut off, and given to each person who accompanied the herd to the hills. It is believed that the milk would not remain in good condition, if the sacred herd had been in any way injuriously affected during its sojourn there. The sacred herd is recruited by certain calves dedicated as members thereof by people of other castes in the neighbourhood of the valley. These calves, born on the 1st of the month Thai (January-February), are dedicated to the god Nandagōpāla, and are known as sanni pasuvu. They are branded on the legs or buttocks, and their ears are slightly torn. They are not used for ploughing or milking, and cannot be sold. They are added to the sacred herd, but the male calves are kept distinct from the male calves thereof. Many miracles are attributed to the successive king bulls. During the fight between the Tottiyans and Kāppiliyans at Dindigul, a king bull left on the rock the permanent imprint of its hoof, which is still believed to be visible. At a subsequent quarrel between the same castes, at Dombachēri, a king bull made the sun turn back in its course, and the shadow is still pointed under a tamarind tree beneath which arbitration took place.

For the assistance rendered by the bull on this occasion, the Māragalas will not use the wood of the tamarind tree, or of the vēla tree, to which the bull was tied, either for fuel or for house-building. The Kāppiliyans have recently (1906) raised Rs. 11,000 by taxing all members of the caste in the Periyakulam tāluk for three years, and have spent this sum in building roomy masonry quarters at Kambam for the sacred herd. Their chief grievance at present is that the same grazing fees are levied on their animals as on mere ordinary cattle, which, they urge, is equivalent to treating gods as equals of men. In the settlement of caste affairs, oaths are taken within the enclosure for the sacred herd.

“Local tradition at Kambam (where a large proportion of the people are Kāppiliyans) says that the Anuppans, another Canarese caste, were in great strength here in olden days, and that quarrels arose between the two bodies, in the course of which the chief of the Kāppiliyans, Rāmachcha Kavundan, was killed. With his dying breath he cursed the Anuppans, and thenceforth they never prospered, and now not one of them is left in the town. A fig tree to the east of the village is shown as marking the place where Rāmachcha’s body was burned; near it is the tank, the Rāmachchankulam; and under the bank of this is his math, where his ashes were deposited.”