Kallan

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Kallan

Of the Kallans of the Madura district in the early part of the last century, an excellent account was written by Mr. T. Turnbull (1817), from which the following extract has been taken. “The Cullaries are said to be in general a brave people, expert in the use of the lance and in throwing the curved stick called vullaree taddee. This weapon is invariably in use among the generality of this tribe; it is about 30 inches in curvature. The word Cullar is used to express a thief of any caste, sect or country, but it will be necessary to trace their progress to that characteristic distinction by which this race is designated both a thief, and an inhabitant of a certain Naud, which was not altogether exempted from paying tribute to the sovereign of Madura.

This race appears to have become hereditary occupiers, and appropriated to themselves various Nauds in different parts of the southern countries; in each of these territories they have a chief among them, whose orders and directions they all must obey. They still possess one common character, and in general are such thieves that the name is very justly applied to them, for they seldom allow any merchandize to pass through their hands without extorting something from the owners, if they do not rob them altogether, and in fact travellers, pilgrims, and Brāhmans are attacked and stript of everything they possess, and they even make no scruple to kill any caste of people, save only the latter. In case a Brāhman happens to be killed in their attempt to plunder, when the fact is made known to the chief, severe corporal punishment is inflicted on the criminals and fines levied, besides exclusion from society for a period of six months. The Maloor Vellaloor Serrugoody Nauds are denominated the Keelnaud, whose inhabitants of the Cullar race are designated by the appellation of Amblacaurs.

“The women are inflexibly vindictive and furious on the least injury, even on suspicion, which prompts them to the most violent revenge without any regard to consequences. A horrible custom exists among the females of the Colleries when a quarrel or dissension arises between them. The insulted woman brings her child to the house of the aggressor, and kills it at her door to avenge herself. Although her vengeance is attended with the most cruel barbarity, she immediately thereafter proceeds to a neighbouring village with all her goods, etc. In this attempt she is opposed by her neighbours, which gives rise to clamour and outrage. The complaint is then carried to the head Amblacaur, who lays it before the elders of the village, and solicits their interference to terminate the quarrel.

In the course of this investigation, if the husband finds that sufficient evidence has been brought against his wife, that she had given cause for provocation and aggression, then he proceeds unobserved by the assembly to his house, and brings one of his children, and, in the presence of witness, kills his child at the door of the woman who had first killed her child at his. By this mode of proceeding he considers that he has saved himself much trouble and expense, which would otherwise have devolved on him. This circumstance is soon brought to the notice of the tribunal, who proclaim that the offence committed is sufficiently avenged. But, should this voluntary retribution of revenge not be executed by the convicted person, the tribunal is prorogued to a limited time, fifteen days generally. Before the expiration of that period, one of the children of that convicted person must be killed. At the same time he is to bear all expenses for providing food, etc., for the assembly during those days.

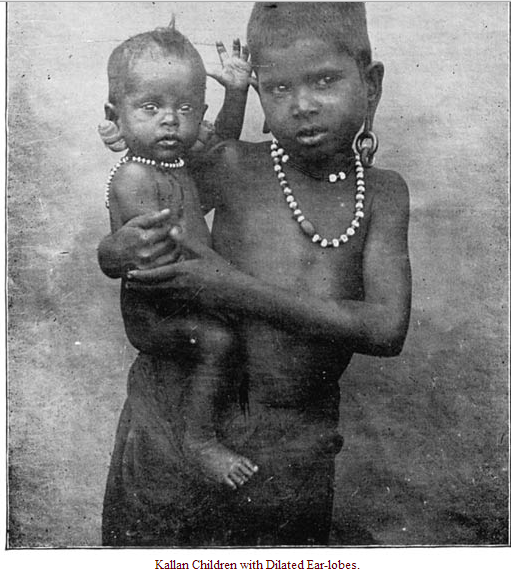

“A remarkable custom prevails both among the males and females in these Nauds to have their ears bored and stretched by hanging heavy rings made of lead so as to expand their ear-laps (lobes) down to their shoulders. Besides this singular idea of beauty attached by them to pendant ears, a circumstance still more remarkable is that, when merchants or travellers pass through these Nauds, they generally take the precaution to insure a safe transit through these territories by counting the friendship of some individual of the Naud by payment of a certain fee, for which he deputes a young girl to conduct the travellers safe through the limits. This sacred guide conducts them along with her finger to her ear. On observing this sign, no Cullary will dare to plunder the persons so conducted. It sometimes happens, in spite of this precaution, that attempts are made to attack the traveller. The girl in such cases immediately tears one of her ear-laps, and returns to spread the report, upon which the complaint is carried before the chief and elders of the Naud, who forthwith convene a meeting in consequence at the Mundoopoolee.

If the violators are convicted, vindictive retaliation ensues. The assembly condemns the offenders to have both their ear-laps torn in expiation of their crime, and, if otherwise capable, they are punished by fines or absolved by money. By this means travellers generally obtain a safe passage through these territories. [Even at the present day, in quarrels between women of the lower castes, long ears form a favourite object of attack, and lobe-tearing cases figure frequently in police records.

“The Maloor Naud was originally inhabited and cultivated by Vellaulers. At a certain period some Cullaries belonging to Vella Naud in the Conjeeveram district proceeded thence on a hunting excursion with weapons consisting of short hand pikes, cudgels, bludgeons, and curved sticks for throwing, and dogs. While engaged in their sport, they observed a peacock resist and attack one of their hounds. The sportsmen, not a little astonished at the sight, declared that this appeared to be a fortunate country, and its native inhabitants and every living creature naturally possessed courage and bravery. Preferring such a country to their Naud in Conjeeveram, they were desirous of establishing themselves here as cultivators. To effect this, they insinuated themselves into the favour of the Vellaulers, and, engaging as their servants, were permitted to remain in these parts, whither they in course of time invited their relations and friends, and to appearance conducted themselves faithfully and obediently to the entire satisfaction of the Vellaulers, and were rewarded for their labour. Some time afterwards, the Vellaulers, exercising an arbitrary sway over the Cullaries, began to inflict condign punishment for offences and misdemeanours committed in their service. This stirred up the wrath of the Cullaries, who gradually acquired the superiority over their masters, and by coercive measures impelled them to a strict observance of the following rules:—

1st.—That, if a Culler was struck by his master in such a manner as to deprive him of a tooth, he was to pay a fine of ten cully chuckrums (money) for the offence.

2nd.—That, if a Culler happened to have one of his ear-laps torn, the Vellauler was to pay a fine of six chuckrums.

3rd.—That if a Culler had his skull fractured, the Vellauler was to pay thirty chuckrums, unless he preferred to have his skull fractured in return.

4th.—That, if a Culler had his arm or leg broke, he was then to be considered but half a man. In such case the offender was required to grant the Culler one cullum of nunjah seed land (wet cultivation), and two koorkums of punjah (dry cultivation), to be held and enjoyed in perpetuity, exclusive of which the Vellauler was required to give the Culler a doopettah (cloth) and a cloth for his wife, twenty cullums of paddy or any other grain, and twenty chuckrums in money for expenses.

5th.—That, if a Culler was killed, the offender was required to pay either a fine of a hundred chuckrums, or be subject to the vengeance of the injured party. Until either of these alternatives was agreed to, and satisfaction afforded, the party injured was at liberty to plunder the offender’s property, never to be restored.

“By this hostile mode of conduct imposed on their masters, together with their extravagant demands, the Vellaulers were reduced to that dread of the Cullers as to court their favour, and became submissive to their will and pleasure, so that in process of time the Cullers not only reduced them to poverty, but also induced them to abandon their villages and hereditary possessions, and to emigrate to foreign countries. Many were even murdered in total disregard of their former solemn promises of fidelity and attachment.

Having thus implacably got rid of their original masters and expelled them from their Naud, they became the rulers of it, and denominated it by the singular appellation of Tun Arrasa Naud signifying a forest only known to its possessors [or tanarasu-nād, i.e., the country governed by themselves]. In short, these Colleries became so formidable at length as to evince a considerable ambition, and to set the then Government at defiance. Allagar Swamy they regarded as the God of their immediate devotion, and, whenever their enterprizes were attended with success, they never failed to be liberal in the performance of certain religious ceremonies to Allagar. To this day they invoke the name of Allagar in all what they do, and they make no objection in contributing whatever they can when the Stalaters come to their villages to collect money or grain for the support of the temple, or any extraordinary ceremonies of the God. The Cullers of this Naud, in the line of the Kurtaukles, once robbed and drove away a large herd of cows belonging to the Prince, who, on being informed of the robbery, and that the calves were highly distressed for want of nourishment, ordered them to be drove out of and left with the cows, wherever they were found. The Cullers were so exceedingly pleased with this instance of the Kurtaukle’s goodness and greatness of mind that they immediately collected a thousand cows (at one cow from every house) in the Naud as a retribution, and drove them along with the plundered cattle to Madura. Whenever a quarrel or dispute happens among them, the parties arrest each other in the name of the respective Amblacaurs, whom they regard as most sacred, and they will only pay their homage to those persons convened as arbitrators or punjayems to settle their disputes.

“During the feudal system that prevailed among these Colleries for a long time, they would on consideration permit the then Government to have any control or authority over them. When tribute was demanded, the Cullers would answer with contempt: ‘The heavens supply the earth with rain, our cattle plough, and we labour to improve and cultivate the land. While such is the case, we alone ought to enjoy the fruits thereof. What reason is there that we should be obedient, and pay tribute to our equal?’

“During the reign of Vizia Ragoonada Saitooputty a party of Colleries, having proceeded on a plundering excursion into the Rāmnād district, carried off two thousand of the Rāja’s own bullocks. The Rāja was so exasperated that he caused forts to be erected at five different places in the Shevagunga and Rāmnād districts, and, on pretext of establishing a good understanding with these Nauttams, he artfully invited the principal men among them, and, having encouraged them by repeatedly conferring marks of his favour, caused a great number to be slain, and a number of their women to be transported to Ramiserum, where they were branded with the marks of the pagoda, and made Deva Dassies or dancing girls and slaves of the temple. The present dancing girls in that celebrated island are said to be the descendants of these women of the Culler tribe.” In the eighteenth century a certain Captain Rumley was sent with troops to check the turbulent Colleries. “He became the terror of the Collerie Naud, and was highly respected and revered by the designation of Rumley Swamy, under which appellation the Colleries afterwards distinguished him.” It is on record that, during the Trichinopoly war, the horses of Clive and Stringer Lawrence were stolen by two Kallan brothers. Tradition says that one of the rooms in Tirumala Nāyakkan’s palace at Madura “was Tirumala’s sleeping apartment, and that his cot hung by long chains from hooks in the roof. One night, says a favourite story, a Kallan made a hole in the roof, swarmed down the chains, and stole the royal jewels. The king promised a jaghir (grant of land) to anyone who would bring him the thief, and the Kallan then gave himself up and claimed the reward. The king gave him the jaghir, and then promptly had him beheaded.”

said to be “a middle-sized dark-skinned tribe found chiefly in the districts of Tanjore, Trichinopoly and Madura, and in the Pudukōta territory. The name Kallan is commonly derived from Tamil kallam, which means theft. Mr. Nelson expresses some doubts as to the correctness of this derivation, but Dr. Oppert accepts it, and no other has been suggested. The original home of the Kallans appears to have been Tondamandalam or the Pallava country, and the head of the class, the Rāja of Pudukōta, is to this day called the Tondaman. There are good grounds for believing that the Kallans are a branch of the Kurumbas, who, when they found their regular occupation as soldiers gone, ‘took to maraudering, and made themselves so obnoxious by their thefts and robberies, that the term kallan, thief, was applied, and stuck to them as a tribal appellation.’ The Rev. W. Taylor, the compiler of the Catalogue Raisonné of Oriental Manuscripts, also identifies the Kallans with the Kurumbas, and Mr. Nelson accepts this conclusion. In the census returns, Kurumban is returned as one of the sub-divisions of the Kallan caste.’

“The Chōla country, or Tanjore,” Mr. W. Francis writes, “seems to have been the original abode of the Kallans before their migration to the Pāndya kingdom after its conquest by the Chōlas about the eleventh century A.D. But in Tanjore they have been greatly influenced by the numerous Brāhmans there, and have taken to shaving their heads and employing Brāhmans as priests. At their weddings also the bridegroom ties the tāli himself, while elsewhere his sister does it. Their brethren across the border in Madura continue to merely tie their hair in a knot, and employ their own folk to officiate as their priests. This advance of one section will doubtless in time enhance the social estimation of the caste as a whole.”

It is further noted, in the Gazetteer of the Tanjore district, that the ambitions of the Kallans have been assisted “by their own readiness, especially in the more advanced portions of the district, to imitate the practices of Brāhmans and Vellālans. Great variations thus occur in their customs in different localities, and a wide gap exists between the Kallans of this district as a whole and those of Madura.”

In the Manual of the Tanjore district, it is stated that “profitable agriculture, coupled with security of property in land, has converted the great bulk of the Kallar and Padeiyachi classes into a contented and industrious population. They are now too fully occupied with agriculture, and the incidental litigation, to think of their old lawless pursuits, even if they had an inclination to follow them. The bulk of the ryotwari proprietors in that richly cultivated part of the Cauvery delta which constituted the greater part of the old tāluk of Tiruvādi are Kallars, and, as a rule, they are a wealthy and well-to-do class. The Kallar ryots, who inhabit the villages along the banks of the Cauvery, in their dress and appearance generally look quite like Vellālas.

Some of the less romantic and inoffensive characteristics of the Kallars in Madura and Tinnevelly are found among the recent immigrants from the south, who are distinguished from the older Kallar colonies by the general term Terkattiyār, literally southerns, which includes emigrants of other castes from the south. The Terkattiyārs are found chiefly in the parts of the district which border on Pudukōta. Kallars of this group grow their hair long all over the head exactly like women, and both men and women enlarge the holes in the lobes of their ears to an extraordinary size by inserting rolls of palm-leaf into them.” The term Terkattiyār is applied to Kallan, Maravan, Agamudaiyan, and other immigrants into the Tanjore district. At Mayaveram, for example, it is applied to Kalians, Agamudaiyans, and Valaiyans.

It is noted, in the Census Report, 1891, that Agamudaiyan and Kallan were returned as sub-divisions of Maravans by a comparatively large number of persons. “Maravan is also found among the sub-divisions of Kallan, and there can be little doubt that there is a very close connection between Kallans, Maravans, and Agamudaiyans.” “The origin of the Kallar caste,” Mr. F. S. Mullaly writes, “as also that of the Maravars and Ahambadayars, is mythologically traced to Indra and Aghalia, the wife of Rishi Gautama. The legend is that Indra and Rishi Gautama were, among others, rival suitors for the hand of Aghalia. Rishi Gautama was the successful one. This so incensed Indra that he determined to win Aghalia at all hazards, and, by means of a cleverly devised ruse, succeeded, and Aghalia bore him three sons, who respectively took the names Kalla, Marava, and Ahambadya. The three castes have the agnomen Thēva or god, and claim to be descendants of Thēvan (Indra).” According to another version of the legend “once upon a time Rishi Gautama left his house to go abroad on business. Dēvendra, taking advantage of his absence, debauched his wife, and three children were the result. When the Rishi returned, one of the three hid himself behind a door, and, as he thus acted like a thief, he was henceforward called Kallan.

Another got up a tree, and was therefore called Maravan from maram, a tree, whilst the third brazened it out and stood his ground, thus earning for himself the name of Ahamudeiyan, or the possessor of pride. This name was corrupted into Ahambadiyan.” There is a Tamil proverb that a Kallan may come to be a Maravan. By respectability he may develop into an Agamudaiyan, and, by slow and small degrees, become a Vellāla, from which he may rise to be a Mudaliar. “The Kallans,” Mr. H. A. Stuart writes, “will eat flesh, excepting beef, and have no scruples regarding the use of intoxicating liquor. They are usually farmers or field-labourers, but many of them are employed as village or other watchmen, and not a few depend for their subsistence upon the proceeds of thefts and robberies.

In Trichinopoly town, householders are obliged to keep a member of the Kallan caste in their service as a protection against the depredations of these thieves, and any refusal to give in to this custom invariably results in loss of property. On the other hand, if a theft should, by any chance, be committed in a house where a Kallan is employed, the articles stolen will be recovered, and returned to the owner. In Madura town, I am informed, a tax of four annas per annum is levied on houses in certain streets by the head of the Kallan caste in return for protection against theft.” In the Census Report, 1901, Mr. Francis records that “the Kallans, Maravans, and Agamudaiyans are responsible for a share of the crime of the southern districts, which is out of all proportion to their strength in them. In 1897, the Inspector-General of Prisons reported that nearly 42 per cent. of the convicts in the Madura jail, and 30 per cent, of those in the Palamcottah jail in Tinnevelly, belonged to one or other of these three castes. In Tinnevelly, in 1894, 131 cattle thefts were committed by men of these three castes against 47 by members of others, which is one theft to 1,497 of the population of the three bodies against one to 37,830 of the other castes. The statistics of their criminality in Trichinopoly and Madura were also bad.

The Kallans had until recently a regular system of blackmail, called kudikāval, under which each village paid certain fees to be exempt from theft. The consequences of being in arrears with their payments quickly followed in the shape of cattle thefts and ‘accidental’ fires in houses. In Madura the villagers recently struck against this extortion. The agitation was started by a man of the Idaiyan or shepherd caste, which naturally suffered greatly by the system, and continued from 1893 to 1896.” The origin of the agitation is said to have been the anger of certain of the Idaiyans with a Kallan Lothario, who enticed away a woman of their caste, and afterwards her daughter, and kept both women simultaneously under his protection. The story of this anti-Kallan agitation is told as follows in the Police Administration Report, 1896. “Many of the Kallans are the kavalgars of the villages under the kaval system. Under that system the kavalgars receive fees, and in some cases rent-free land for undertaking to protect the property of the villagers against theft, or to restore an equivalent in value for anything lost. The people who suffer most at the hands of the Kallars are the shepherds (Kōnans or Idaiyans). Their sheep and goats form a convenient subject for the Kallar’s raids. They are taken for kaval fees alleged to be overdue, and also stolen, again to be restored on the payment of blackmail. The anti-Kallar movement was started by a man of the shepherd caste, and rapidly spread. Meetings of villagers were held, at which thousands attended.

They took oath on their ploughs to dispense with the services of the Kallars; they formed funds to compensate such of them as lost their cattle, or whose houses were burnt; they arranged for watchmen among themselves to patrol the villages at night; they provided horns to be sounded to carry the alarm in cases of theft from village to village, and prescribed a regular scale of fines to be paid by those villagers who failed to turn out on the sound of the alarm. The Kallans in the north in many cases sold their lands, and left their villages, but in some places they showed fight. For six months crime is said to have ceased absolutely, and, as one deponent put it, people even left their buckets at the wells. In one or two places the Kallans gathered in large bodies in view to overawe the villagers, and riots followed. In one village there were three murders, and the Kallar quarter was destroyed by fire, but whether the fire was the work of Kōnans or Kallars has never been discovered. In August, large numbers of villagers attacked the Kallars in two villages in the Dindigul division, and burnt the Kallar quarters.” “The crimes,” Mr. F. S. Mullaly writes, “that Kallars are addicted to are dacoity in houses or on highways, robbery, house-breaking and cattle-stealing. They are usually armed with vellari thadis or clubs (the so-called boomerangs) and occasionally with knives similar to those worn by the inhabitants of the western coast. Their method of house-breaking is to make the breach in the wall under the door. A lad of diminutive size then creeps in, and opens the door for the elders. Jewels worn by sleepers are seldom touched. The stolen property is hidden in convenient places, in drains, wells, or straw stacks, and is sometimes returned to the owner on receipt of blackmail from him called tuppu-kūli or clue hire. The women seldom join in crimes, but assist the men in their dealings (for disposal of the stolen property) with the Chettis.” It is noted by the Abbé Dubois that the Kallars “regard a robber’s occupation as discreditable neither to themselves, nor to their fellow castemen, for the simple reason that they consider robbery a duty, and a right sanctioned by descent. If one were to ask of a Kallar to what people he belonged, he would coolly answer, I am a robber.”

It is recorded, in the Gazetteer of the Madura district, that “dacoity of travellers at night used to be the favourite pastime of the Kallans, and their favourite haunts the various roads leading out of Madura, and that from Ammayanāyakkanūr to Periyakulam. The method adopted consisted in threatening the driver of the cart, and then turning the vehicle into the ditch so that it upset. The unfortunate travellers were then forced by some of the gang to sit at the side of the road, with their backs to the cart and their faces to the ground, while their baggage was searched for valuables by the remainder. The gangs which frequented these roads have now broken up, and the caste has practically quitted road dacoity for the simpler, more paying, and less risky business of stealing officials’ office-boxes and ryots’ cattle. Cattle-theft is now the most popular calling among them. They are clever at handling animals, and probably the popularity of the jallikats (see Maravan) has its origin in the demands of a life, which always included much cattle-lifting. The stolen animals are driven great distances (as much as 20 or 30 miles) on the night of the theft, and are then hidden for the day either in a friend’s house, or among hills and jungles.

The next night they are taken still further, and again hidden. Pursuit is by this time hopeless, as the owner has no idea even in which direction to search. He, therefore, proceeds to the nearest go-between (these individuals are well-known to every one), and offers him a reward if he will bring back the cattle. This reward is called tuppu-kūli, or payment for clues, and is very usually as much as half the value of the animals stolen. The Kallan undertakes to search for the lost bullocks, returns soon, and states that he has found them, receives his tuppu-kūli, and then tells the owner of the property that, if he will go to a spot named, which is usually in some lonely neighbourhood, he will find his cattle tied up there. This information is always correct. If, on the other hand, the owner reports the theft to the police, no Kallan will help him to recover his animals, and these are eventually sold in other districts or Travancore, or even sent across from Tuticorin to Ceylon. Consequently, hardly any cattle-thefts are ever reported to the police. Where the Kallans are most numerous, the fear of incendiarism induces people to try to afford a tiled or terraced roof, instead of being content with thatch. The cattle are always tied up in the houses at night. Fear of the Kallans prevents them from being left in the fields, and they may be seen coming into the villages every evening in scores, choking every one with the dust they kick up, and polluting the village site (instead of manuring the land) for twelve hours out of every twenty-four. Buffaloes are tied up outside the houses.

Kallans do not care to steal them, as they are of little value, are very troublesome when a stranger tries to handle them, and cannot travel fast or far enough to be out of reach of detection by daybreak. The Kallans’ inveterate addiction to dacoity and theft render the caste to this day a thorn in the flesh of the authorities. A very large proportion of the thefts committed in the district are attributable to them. Nor are they ashamed of the fact. One of them defended his class by urging that every other class stole, the official by taking bribes, the vakil (law pleader) by fostering animosities, and so pocketing fees, the merchant by watering the arrack (spirit) and sanding the sugar, and so on, and that the Kallans differed from these only in the directness of their methods. Round about Mēlūr, the people of the caste are taking energetically to wet cultivation, to the exclusion of cattle-lifting, with the Periyār water, which has lately been brought there. In some of the villages to the south of that town, they have drawn up a formal agreement (which has been solemnly registered, and is most rigorously enforced by the headmen), forbidding theft, recalling all the women who have emigrated to Ceylon and elsewhere, and, with an enlightenment which puts other communities to shame, prohibiting several other unwise practices which are only too common, such as the removal from the fields of cow-dung for fuel, and the pollution of drinking-water tanks (ponds) by stepping into them. Hard things have been said about the Kallans, but points to their credit are the chastity of their women, the cleanliness they observe in and around their villages, and their marked sobriety. A toddy-shop in a Kallan village is seldom a financial success.”

From a recent note, I gather the following additional information concerning tuppu-kuli. “The Kallans are largely guilty of cattle-thefts. In many cases, they return the cattle on receiving tuppu-kuli. The official returns do not show many of these cases. No cattle-owner thinks of reporting the loss of any of his cattle. Naturally his first instinct is that it might have strayed away, being live property. The tuppu-kuli system generally helps the owner to recover his lost cattle. He has only to pay half of its real value, and, when he recovers his animal, he goes home with the belief that he has really made a profitable bargain. There is no matter for complaint, but, on the other hand, he is glad that he got back his animal for use, often at the most opportune time. Cattle are indispensable to the agriculturist at all times of the year. Perhaps, sometimes, when the rains fail, he may not use them. But if, after a long drought, there is a shower, immediately every agriculturist runs to his field with his plough and cattle, and tills it. If, at such a time, his cattle be stolen, he considers as though he were beaten on his belly, and his means of livelihood gone. No cattle will be available then for hire.

There is nothing that he will not part with, to get back his cattle. There is then the nefarious system of tuppu-kuli offering itself, and he freely resorts to it, and succeeds in getting back his lost cattle sooner or later. On the other hand, if a complaint is made to the Village Magistrate or Police, recovery by this channel is impossible. The tuppu-kuli agents have their spies or informants everywhere, dogging the footsteps of the owner of the stolen cattle, and of those who are likely to help him in recovering it. As soon as they know the case is recorded in the Police station, they determine not to let the animal go back to its owner at any risk, unless some mutual friend intervenes, and works mightily for the recovery, in which case the restoration is generally through the pound. Such a restoration is, primâ facie, cattle-straying, for only stray cattle are taken to the pound. This, too, is done after a good deal of hard swearing on both sides not to hand over the offender to the authorities.” In connection with the ‘vellari thadi’ referred to above, Dr. Oppert writes that “boomerangs are used by the Tamil Maravans and Kallans when hunting deer. The Madras Museum collection contains three (two ivory, one wooden) from the Tanjore a rmoury. In the arsenal of the Pudukkōttai Rāja a stock of wooden boomerangs is always kept. Their name in Tamil is valai tadi (bent stick).” Concerning these boomerangs, the Dewān of Pudukkōttai writes to me as follows. “The valari or valai tadi is a short weapon, generally made of some hard-grained wood. It is also sometimes made of iron. It is crescent-shaped, one end being heavier than the other, and the outer edge is sharpened. Men trained in the use of the weapon hold it by the lighter end, whirl [71]it a few times over their shoulders to give it impetus, and then hurl it with great force against the object aimed at. It is said that there were experts in the art of throwing the valari, who could at one stroke despatch small game, and even man. No such experts are now forthcoming in the State, though the instrument is reported to be occasionally used in hunting hares, jungle fowl, etc. Its days, however, must be counted as past. Tradition states that the instrument played a considerable part in the Poligar wars of the last century. But it now reposes peacefully in the households of the descendants of the rude Kallan and Maravan warriors, who plied it with such deadly effect in the last century, preserved as a sacred relic of a chivalric past along with other old family weapons in their pūja room, brought out and scraped and cleaned on occasions like the Ayudha pūja day (when worship is paid to weapons and implements of industry), and restored to its place of rest immediately afterwards.”

The sub-divisions of the Kallans, which were returned in greatest numbers at the census, 1891, were Īsanganādu (or Visangu-nādu), Kungiliyan, Mēnādu, Nāttu, Piramalainādu, and Sīrukudi. In the Census Report, 1901, it is recorded that “in Madura the Kallans are divided into ten main endogamous divisions which are territorial in origin. These are

(1) Mēl-nādu,

(2) Sīrukudi-nādu,

(3) Vellūr-nādu,

(4) Malla-kōttai nādu,

(5) Pākanēri,

(6) Kandramānikkam or Kunnan-kōttai nādu,

(7) Kandadēvi,

(8) Puramalai-nādu,

(9) Tennilai-nādu, and

(10) Pālaya-nādu.

The headman of the Puramalai-nādu section is said to be installed by Idaiyans (herdsmen), but what the connection between the two castes may be is not clear. The termination nādu means a country. These sections are further divided into exogamous sections called vaguppus. The Mēl-nādu Kallans have three sections called terus or streets, namely, Vadakku-teru (north street), Kilakku-teru (east street), and Tērku-teru (south street). The Sīrukudi Kallans have vaguppus named after the gods specially worshipped by each, such as Āndi, Mandai, Aiyanar, and Vīramāngāli. Among the Vellūr-nādu Kallans the names of these sections seem merely fanciful. Some of them are Vēngai puli (cruel-handed tiger), Vekkāli puli (cruel-legged tiger), Sāmi puli (holy tiger), Sem puli (red tiger), Sammatti makkal (hammer men), Tirumān (holy deer), and Sāyumpadai tāngi (supporter of the vanquished army). A section of the Tanjore Kallans names its sections from sundry high-sounding titles meaning King of the Pallavas, King of Tanjore, conqueror of the south, mighty ruler, and so on.”

Portions of the Madura and Tanjore districts are divided into areas known as nādus, a name which, as observed by Mr. Nelson, is specially applicable to Kallan tracts. In each nādu a certain caste, called the Nāttan, is the predominant factor in the settlement of social questions which arise among the various castes living within the nādu. Round about Devakotta in the Sivaganga zamindari there are fourteen nādus, representatives of which meet once a year at Kandadēvi, to arrange for the annual festival at the temple dedicated to Swarnamurthi Swāmi. The four nādus Unjanai, Sembonmari, Iravaseri, and Tennilai in the same zamindari constitute a group, of which the last is considered the chief nādu, whereat caste questions must come up for settlement.

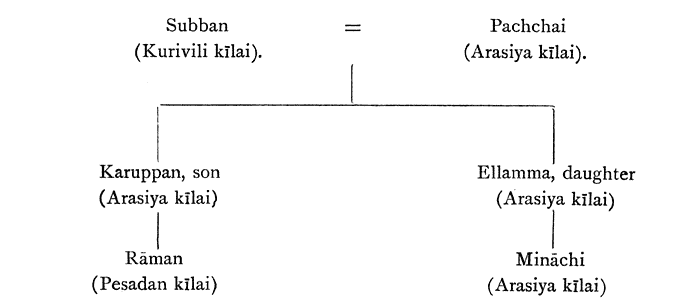

For marriage purposes these four nādus constitute an endogamous section, which is sub-divided into septs or karais. Among the Vallambans these karais are exogamous, and run in the male line. But, among the Kallans, the karai is recognised only in connection with property. A certain tract of land is the property of a particular karai, and the legal owners thereof are members of the same karai. When the land has to be disposed of, this can only be effected with the consent of representatives of the karai. The Nāttar Kallans of Sivaganga have exogamous septs called kīlai or branches, which, as among the Maravans, run in the female line, i.e., a child belongs to the mother’s, not the father’s, sept. In some castes, and even among Brāhmans, though contrary to strict rule, it is permissible for a man to marry his sister’s daughter. This is not possible among the Kallans who have kīlais such as those referred to, because the maternal uncle of a girl, the girl, and her mother all belong to the same sept. But the children of a brother and sister may marry, because they belong to different kīlais, i.e., those of their respective mothers.

In the above example, the girl Mināchi may not marry Karuppan, as both are members of the same kīlai. But she ought, though he be a mere boy, to marry Rāman, who belongs to a different sept. It is noted that, among the Sivaganga Kallans, “when a member of a certain kīlai dies, a piece of new cloth should be given to the other male member of the same kīlai by the heir of the deceased. The cloth thus obtained should be given to the sister of the person obtaining it. If her brother fails to do so, her husband will consider himself degraded, and consequently will divorce her.” Round about Pudukkōttai and Tanjore, the Visangu-nādu Kallans have exogamous septs called pattapēru, and they adopt the sept name as a title, e.g., Muthu Udaiyān, Karuppa Tondaman, etc. It is noted, in the Gazetteer of the Tanjore district, that the sub-divisions of the Kallans are split into groups, e.g., Onaiyan (wolfish), Singattān (lion-like), etc.

It is a curious fact that the Puramalai-nādu Kallans practice the rite of circumcision. The origin of this custom is uncertain, but it has been suggested that it is a survival of a forcible conversion to Muhammadanism of a section of the Kurumbas who fled northwards on the downfall of their kingdom. At the time appointed for the initiatory ceremony, the Kallan youth is carried on the shoulders of his maternal uncle to a grove or plain outside the village, where betel is distributed among those who have assembled, and the operation is performed by a barber-surgeon. En route to the selected site, and throughout the ceremony, the conch shell (musical instrument) is blown. The youth is presented with new cloths. It is noted, in the Gazetteer of the Madura district, that “every Kallan boy has a right to claim the hand of his paternal aunt’s daughter in marriage. This aunt bears the expenses connected with his circumcision. Similarly, the maternal uncle pays the costs of the rites which are observed when a girl attains maturity, for he has a claim on the girl as a bride for his son. The two ceremonies are performed at one time for large batches of boys and girls. On an auspicious day, the young people are all feasted, and dressed in their best, and repair to a river or tank (pond). The mothers of the girls make lamps of plantain leaves, and float them on the water, and the boys are operated on by the local barber.” It is stated, in the Census Report, 1901, that the Sīrukudi Kallans use a tāli, on which the Muhammadan badge of a crescent and star is engraved.

In connection with marriage among the Kallans, it is noted by Mr. S. M. Natesa Sastri that “at the Māttupongal feast, towards evening, festoons of aloe fibre and cloths containing coins are tied to the horns of bullocks and cows, and the animals are driven through the streets with tom-tom and music. In the villages, especially those inhabited by the Kallans in Madura and Tinnevelly, the maiden chooses as her husband him who has safely untied and brought to her the cloth tied to the horn of the fiercest bull. The animals are let loose with their horns containing valuables, amidst the din of tom-tom and harsh music, which terrifies and bewilders them. They run madly about, and are purposely excited by the crowd. A young Kalla will declare that he will run after such and such a bull—and this is sometimes a risky pursuit—and recover the valuables tied to its horn. The Kallan considers it a great disgrace to be injured while chasing the bull.”

A poet of the early years of the present era, quoted by Mr. Kanakasabhai Pillai, describes this custom as practiced by the shepherd castes in those days. “A large area of ground is enclosed with palisades and strong fences. Into the enclosure are brought ferocious bulls with sharpened horns. On a spacious loft, overlooking the enclosure, stand the shepherd girls, whom they intend to give away in marriage. The shepherd youths, prepared for the fight, first pray to their gods, whose images are placed under old banian or peepul trees, or at watering places. They then deck themselves with garlands made of the bright red flowers of the kānthal, and the purple flowers of the kāya.

At a signal given by the beating of drums, the youths leap into the enclosure, and try to seize the bulls, which, frightened by the noise of the drums, are now ready to charge anyone who approaches them. Each youth approaches a bull, which he chooses to capture. But the bulls rush furiously, with tails raised, heads bent down, and horns levelled at their assailants. Some of the youths face the bulls boldly, and seize their horns. Some jump aside, and take hold of their tails. The more wary young men cling to the animals till they force them to fall on the ground. Many a luckless youth is now thrown down. Some escape without a scratch, while others are trampled upon or gored by the bulls. Some, though wounded and bleeding, again spring on the bulls. A few, who succeed in capturing the animals, are declared the victors of that day’s fight. The elders then announce that the bull-fight is over. The wounded are carried out of the enclosure, and attended to immediately, while the victors and the brides-elect repair to an adjoining grove, and there, forming into groups, dance joyously before preparing for their marriage.”

In an account of marriage among the Kallans, Mr. Nelson writes that “the most proper alliance in the opinion of a Kallan is one between a man and the daughter of his father’s sister, and, if an individual have such a cousin, he must marry her, whatever disparity there may be between their respective ages. A boy of fifteen must marry such a cousin, even if she be thirty or forty years old, if her father insists upon his so doing. Failing a cousin of this sort, he must marry his aunt or his niece, or any near relative. If his father’s brother has a daughter, and insists upon him marrying her he cannot refuse; and this whatever may be the woman’s age. One of the customs of the western Kallans is specially curious. It constantly happens that a woman is the wife of ten, eight, six, or two husbands, who are held to be the fathers jointly and severally of any children that may be born of her body, and, still more curiously, when the children grow up they, for some unknown reason, invariably style themselves the children not of ten, eight or six fathers as the case may be, but of eight and two, six and two, or four and two fathers. When a wedding takes place, the sister of the bridegroom goes to the house of the parents of the bride, and presents them with twenty-one Kāli fanams (coins) and a cloth, and, at the same time, ties some horse-hair round the bride’s neck. She then brings her and her relatives to the house of the bridegroom, where a feast is prepared.

Sheep are killed, and stores of liquor kept ready, and all partake of the good cheer provided. After this the bride and bridegroom are conducted to the house of the latter, and the ceremony of an exchange between them of vallari thadis or boomerangs is solemnly performed. Another feast is then given in the bride’s house, and the bride is presented by her parents with one markāl of rice and a hen. She then goes with her husband to his house. During the first twelve months after marriage, it is customary for the wife’s parents to invite the pair to stay with them a day or two on the occasion of any feast, and to present them on their departure with a markāl of rice and a cock. At the time of the first Pongal feast after the marriage, the presents customarily given to the son-in-law are five markāls of rice, five loads of pots and pans, five bunches of plantains, five cocoanuts, and five lumps of jaggery (crude sugar). A divorce is easily obtained on either side. A husband dissatisfied with his wife can send her away if he be willing at the same time to give her half of his property, and a wife can leave her husband at will upon forfeiture of forty-two Kāli fanams. A widow may marry any man she fancies, if she can induce him to make her a present of ten fanams.”

In connection with the foregoing account, I am informed that, among the Nāttar Kallans, the brother of a married woman must give her annually at Pongal a present of rice, a goat, and a cloth until her death. The custom of exchanging boomerangs appears to be fast becoming a tradition. But, there is a common saying still current “Send the valari tadi, and bring the bride.” As regards the horse-hair, which is mentioned as being tied round the bride’s neck, I gather that, as a rule, the tāli is suspended from a cotton thread, and the horse-hair necklet may be worn by girls prior to puberty and marriage, and by widows. This form of necklet is also worn by females of other castes, such as Maravans, Valaiyans, and Morasa Paraiyans. Puramalai Kallan women can be distinguished by the triangular ornament, which is attached to the tāli string. It is stated, in the Gazetteer of the Madura district, that “when a girl has attained maturity, she puts away the necklace of coloured beads she wore as a child, and dons the horse-hair necklet, which is characteristic of the Kallan woman. This she retains till death, even if she becomes a widow. The richer Kallans substitute for the horse-hair a necklace of many strands of fine silver wire. In Tirumangalam, the women often hang round their necks a most curious brass and silver pendant, six or eight inches long, and elaborately worked.”

It is noted in the Census Report, 1891, that as a token of divorce “a Kallan gives his wife a piece of straw in the presence of his caste people. In Tamil the expression ‘to give a straw’ means to divorce, and ‘to take a straw’ means to accept divorce.”

In their marriage customs, some Kallans have adopted the Purānic form of rite owing to the influence of Brāhman purōhits, and, though adult marriage is the rule, some Brāhmanised Kallans have introduced infant marriage. To this the Puramalai section has a strong objection, as, from the time of marriage, they have to give annually till the birth of the first child a present of fowls, rice, a goat, jaggery, plantains, betel, turmeric, and condiments. By adult marriage the time during which this present has to be made is shortened, and less expenditure thereon is incurred. In connection with the marriage ceremonies as carried out by some Kallans,

I gather that the consent of the maternal uncle of a girl to her marriage is essential. For the betrothal ceremony, the father and maternal uncle of the future bridegroom proceed to the girl’s house, where a feast is held, and the date fixed for the wedding written on two rolls of palm leaf dyed with turmeric or red paper, which are exchanged between the maternal uncles. On the wedding day, the sister of the bridegroom goes to the house of the bride, accompanied by women, some of whom carry flowers, cocoanuts, betel leaves, turmeric, leafy twigs of Sesbania grandiflora, paddy (unhusked rice), milk, and ghī (clarified butter). A basket containing a female cloth, and the tāli string wrapped up in a red cloth borrowed from a washerman, is given to a sister of the bridegroom or to a woman belonging to his sept. On the way to the bride’s house, two of the women blow chank shells (musical instrument).

The bride’s people question the bridegroom’s party as to his sept, and they ought to say that he belongs to Indra kūlam, Thalavala nādu, and Ahalya gōtra. The bridegroom’s sister, taking up the tāli, passes it round to be touched by all present, and ties the string, which is decorated with flowers, tightly round the bride’s neck amid the blowing of the conch shell. The bride is then conducted to the home of the bridegroom, whence they return to her house on the following day. The newly married couple sit on a plank, and coloured rice-balls or coloured water are waved, while women yell out “killa, illa, illa; killa, illa, illa.” This ceremony is called kulavi idal, and is sometimes performed by Kallan women during the tāli-tying.

The following details relating to the marriage ceremonies are recorded in the Gazetteer of the Tanjore district. “The arrival of the bridegroom has been described as being sometimes especially ceremonious. Mounted on a horse, and attended by his maternal uncle, he is met by a youth from the bride’s house, also mounted, who conducts the visitors to the marriage booth. Here he is given betel leaves, areca nuts, and a rupee by the bride’s father, and his feet are washed in milk and water, and adorned with toe-rings by the bride’s mother. The tāli is suspended from a necklet of gold or silver instead of cotton thread, but this is afterwards changed to cotton for fear of offending the god Karuppan. A lamp is often held by the bridegroom’s sister, or some married woman, while the tāli is being tied. This is left unlighted by the Kallans for fear it should go out, and thus cause an evil omen. The marriage tie is in some localities very loose. Even a woman who has borne her husband many children may leave him if she likes, to seek a second husband, on condition that she pays him her marriage expenses. In this case (as also when widows are remarried), the children are left in the late husband’s house. The freedom of the Kallan women in these matters is noticed in the proverb that, “though there may be no thread in the spinning-rod, there will always be a (tāli) thread on the neck of a Kallan woman,” or that “though other threads fail, the thread of a Kallan woman will never do so.”

By some Kallans pollution is, on the occasion of the first menstrual period, observed for seven or nine days. On the sixteenth day, the maternal uncle of the girl brings a sheep or goat, and rice. She is bathed and decorated, and sits on a plank while a vessel of water, coloured rice, and a measure filled with paddy with a style bearing a betel leaf struck on it, are waved before her. Her head, knees, and shoulders are touched with cakes, which are then thrown away. A woman, conducting the girl round the plank, pours water from a vessel on to a betel leaf held in her hand, so that it falls on the ground at the four cardinal points of the compass, which the girl salutes.

A ceremony is generally celebrated in the seventh month of pregnancy, for which the husband’s sister prepares pongal (cooked rice). The pregnant woman sits on a plank, and the rice is waved before her. She then stands up, and bends down while her sister-in-law pours milk from a betel or pīpal (Ficus religiosa) leaf on her back. A feast brings the ceremony to a close. Among [ the Vellūr-nādu Kallans patterns are said to be drawn on the back of the pregnant woman with rice-flour, and milk is poured over them. The husband’s sister decorates a grindstone in the same way, invokes a blessing on the woman, and expresses a hope that she may have a male child as strong as a stone.

When a child is born in a family, the entire family observes pollution for thirty days, during which entrance into a temple is forbidden. Among the Nāttar Kallans, children are said to be named at any time after they are a month old. But, among the Puramalai Kallans, a first-born female child is named on the seventh day, after the ear-boring ceremony has been performed. “All Kallans,” Mr. Francis writes, “put on sacred ashes, the usual mark of a Saivite, on festive occasions, but they are nevertheless generally Vaishnavites. The dead are usually buried, and it is said that, at funerals, cheroots are handed round, which those present smoke while the ceremony proceeds.” Some Kallans are said, when a death occurs in a family, to put a pot filled with dung or water, a broomstick, and a fire-brand at some place where three roads meet, or in front of the house, in order to prevent the ghost from returning.

It is recorded, in the Gazetteer of the Madura district, that “the Kilnād Kallans usually bury their dead. Lamps are periodically lighted on the tomb, and it is whitewashed annually. The Piramalainād division usually burn the dead. If a woman dies when with child, the baby is taken out, and placed alongside her on the pyre. This, it may be noted, is the rule with most castes in this district, and, in some communities, the relations afterwards put up a stone burden-rest by the side of a road, the idea being that the woman died with her burden, and so her spirit rejoices to see others lightened of theirs. Tradition says that the caste came originally from the north.

The dead are buried with their faces laid in that direction; and, when pūja is done to Karuppanaswāmi, the caste god, the worshippers turn to the north.” According to Mr. H. A. Stuart “the Kallans are nominally Saivites, but in reality the essence of their religious belief is devil-worship. Their chief deity is Alagarswāmi, the god of the great Alagar Kōvil twelve miles to the north of the town of Madura. To this temple they make large offerings, and the Swāmi, called Kalla Alagar, has always been regarded as their own peculiar deity.” The Kallans are said by Mr. Mullaly to observe omens, and consult their household gods before starting on depredations. “Two flowers, the one red and the other white, are placed before the idol, a symbol of their god Kalla Alagar. The white flower is the emblem of success.

A child of tender years is told to pluck a petal of one of the two flowers, and the undertaking rests upon the choice made by the child.” In like manner, when a marriage is contemplated among the Idaiyans, the parents of the prospective bride and bridegroom go to the temple, and throw before the idol a red and white flower, each wrapped in a betel leaf. A small child is then told to pick up one of the leaves. If the one selected contains the white flower, it is considered auspicious, and the marriage will take place.

In connection with the Alagar Kōvil, I gather that, when oaths are to be taken, the person who is to swear is asked to worship Kallar Alagar, and, with a parivattam (cloth worn as a mark of respect in the presence of the god) on his head, and a garland round his neck, should stand on the eighteenth step of the eighteen steps of Karuppanaswāmi, and say: “I swear before Kallar Alagar and Karuppannaswāmi that I have acted rightly, and so on. If the person swears falsely, he dies on the third day; if truly the other person meets with the same fate.”

It was noted by Mr. M. J. Walhouse, that “at the bull games (jellikattu) at Dindigul, the Kallans can alone officiate as priests, and consult the presiding deity. On this occasion they hold quite a Saturnalia of lordship and arrogance over the Brāhmans.” It is recorded, in the Gazetteer of the Madura district, that “the keenness of the more virile sections of the community (especially the Kallans), in this game, is extraordinary, and, in many villages, cattle are bred and reared specially for it. The best jallikats are to be seen in the Kallan country in Tirumangalam, and next come those in Mēlūr and Madura tāluks.” (See also Maravan.)

It is recorded, in the Gazetteer of the Madura district, that Karuppan is “essentially the god of the Kallans, especially of the Kallans of the Mēlūr side. In those parts, his shrine is usually the Kallans’ chāvadi (assembly place). His priests are usually Kallans or Kusavans. Alagarswāmi (the beautiful god) is held in special veneration by the Kallans, and is often popularly called the Kallar Alagar. The men of this caste have the right to drag his car at the car festival, and, when he goes (from Alagar Kōvil) on his visit to Madura, he is dressed as a Kallan, exhibits the long ears characteristic of that caste, and carries the boomerang and club, which were of their old favourite weapons. It is whispered that Kallan dacoits invoke his aid when they are setting out on marauding expeditions, and, if they are successful therein, put part of their ill-gotten gains into the offertory (undial) box, which is kept at his shrine.” For the following note I am indebted to the Rev. J. Sharrock.

“The chief temple of the Kallans is about ten miles west of Madura, and is dedicated to Alagarswāmi, said to be an incarnation of Vishnu, but also said to be the brother of Mīnātchi (the fish-eyed or beautiful daughter of the Pāndya king of Madura). Now Mīnātchi has been married by the Brāhmans to Siva, and so we see Hinduism wedded to Dravidianism, and the spirit of compromise, the chief method of conversion adopted by the Brāhmans, carried to its utmost limit. At the great annual festival, the idol of Alagarswāmi is carried, in the month of Chittra (April-May), to the temple of Mīnātchi, and the banks of the river Vaiga swarm with two to three lakhs of worshippers, a large proportion of whom are Kallans. At this festival, the Kallans have the right of dragging with a rope the car of Alagarswāmi, though other people may join in later on. As Alagarswāmi is a vegetarian, no blood sacrifice is offered to him. This is probably due to the influence of Brāhmanism, for, in their ordinary ceremonies, the Kallans invariably slaughter sheep as sacrifices to propitiate their deities.

True to their bold and thievish instincts, the Kallans do not hesitate to steal a god, if they think he will be of use to them in their predatory excursions, and are not afraid to dig up the coins or jewels that are generally buried under an idol. Though they entertain little dread of their own village gods, they are often afraid of others that they meet far from home, or in the jungles when they are engaged in one of their stealing expeditions. As regards their own village gods, there is a sort of understanding that, if they help them in their thefts, they are to have a fair share of the spoil, and, on the principle of honesty among thieves, the bargain is always kept. At the annual festival for the village deities, each family sacrifices a sheep, and the head of the victim is given to the pūjāri (priest), while the body is taken home by the donor, and partaken of as a communion feast. Two at least of the elements of totem worship appear here: there is the shedding of the sacrificial blood of an innocent victim to appease the wrath of the totem god, and the common feasting together which follows it.

The Brāhmans sometimes join in these sacrifices, but of course take no part of the victim, the whole being the perquisite of the pūjāri, and there is no common participation in the meal. When strange deities are met with by the Kallans on their thieving expeditions, it is usual to make a vow that, if the adventure turns out well, part of the spoil shall next day be left at the shrine of the god, or be handed over to the pūjāri of that particular deity. They are afraid that, if this precaution be not taken, the god may make them blind, or cause them to be discovered, or may go so far as to knock them down, and leave them to bleed to death. If they have seen the deity, or been particularly frightened or otherwise specially affected by these unknown gods, instead of leaving a part of the body, they adopt a more thorough method of satisfying the same.

After a few days they return at midnight to make a special sacrifice, which of course is conducted by the particular pūjāri, whose god is to be appeased. They bring a sheep with rice, curry-stuffs and liquors, and, after the sacrifice, give a considerable share of these dainties, together with the animal’s head, to the pūjāri, as well as a sum of money for making the pūja (worship) for them. Some of the ceremonies are worth recording. First the idol is washed in water, and a sandal spot is put on the forehead in the case of male deities, and a kunkuma spot in the case of females. Garlands are placed round the neck, and the bell is rung, while lamps are lighted all about. Then the deity’s name is repeatedly invoked, accompanied by beating on the udukku. This is a small drum which tapers to a narrow waist in the middle, and is held in the left hand of the pūjāri with one end close to his left ear, while he taps on it with the fingers of his right hand. Not only is this primitive music pleasing to the ears of his barbarous audience, but, what is more important, it conveys the oracular communications of the god himself.

By means of the end of the drum placed close to his ear, the pūjāri is enabled to hear what the god has to say of the predatory excursion which has taken place, and the pūjāri (who, like a clever gypsy, has taken care previously to get as much information of what has happened as possible) retails all that has occurred during the exploit to his wondering devotees.

In case his information is incomplete, he is easily able to find out, by a few leading questions and a little cross-examination of these ignorant people, all that he needs to impress them with the idea that the god knows all about their transactions, having been present at their plundering bout. At all such sacrifices, it is a common custom to pour a little water over the sheep, to see if it will shake itself, this being invariably a sign of the deity’s acceptance of the animal offered. In some sacrifices, if the sheep does not shake itself, it is rejected, and another substituted for it; and, in some cases (be it whispered, when the pūjāri thinks the sheep too thin and scraggy), he pours over it only a little water, and so demands another animal. If, however, the pūjāri, as the god’s representative, is satisfied, he goes on pouring more and more water till the half-drenched animal has to shake itself, and so signs its own death-warrant. All who have ventured forth in the night to take part in the sacrifice then join together in the communal meal.

An illustration of the value of sacrifices may here be quoted, to show how little value may be attached to an oath made in the presence of a god. Some pannaikārans (servants) of a Kallan land-owner one day stole a sheep, for which they were brought up before the village munsif. When they denied the theft, the munsif took them to their village god, Karuppan (the black brother), and made them swear in its presence. They perjured themselves again, and were let off. Their master quietly questioned them afterwards, asking them how they dared swear so falsely before their own god, and to this they replied ‘While we were swearing, we were mentally offering a sacrifice to him of a sheep’ (which they subsequently carried out), to pacify him for the double crime of stealing and perjury.”

As a typical example of devil worship, the practice of the Valaiyans and Kallans of Orattanādu in the Tanjore district is described by Mr. F. R. Hemingway. “Valaiyan houses have generally an odiyan (Odina Wodier) tree in the backyard, wherein the devils are believed to live, and among Kallans every street has a tree for their accommodation. They are propitiated ]at least once a year, the more virulent under the tree itself, and the rest in the house, generally on a Friday or Monday. Kallans attach importance to Friday in Ādi (July and August), the cattle Pongal day in Tai (January and February), and Kartigai day in the month Kartigai (November and December). A man, with his mouth covered with a cloth to indicate silence and purity, cooks rice in the backyard, and pours it out in front of the tree, mixed with milk and jaggery (crude sugar). Cocoanuts and toddy are also placed there. These are offered to the devils, represented in the form of bricks or mud images placed at the foot of the tree, and camphor is set alight. A sheep is then brought and slaughtered, and the devils are supposed to spring one after another from the tree into one of the bystanders. This man then becomes filled with the divine afflatus, works himself up into a kind of frenzy, becomes the mouthpiece of the spirits, pronounces their satisfaction or the reverse at the offerings, and gives utterance to cryptic phrases, which are held to foretell good or evil fortune to those in answer to whom they are made. When all the devils in turn have spoken and vanished, the man recovers his senses. The devils are worshipped in the same way in the houses, except that no blood is shed. All alike are propitiated by animal sacrifices.”

The Kallans are stated by Mr. Hemingway to be very fond of bull-baiting. This is of two kinds. The first resembles the game played by other castes, except that the Kallans train their animals for the sport, and have regular meetings, at which all the villagers congregate. These begin at Pongal, and go on till the end of May. The sport is called tolu mādu (byre bull). The best animals for it are the Pulikkolam bulls from the Madura district. The other game is called pāchal mādu (leaping bull). In this, the animals are tethered to a long rope, and the object of the competition is to throw the animal, and keep it down. A bull which is good at the game, and difficult to throw, fetches a very high price. It is noted in the Gazetteer of the Tanjore district, that “the Kallans have village caste panchayats (councils) of the usual kind, but in some places they are discontinuing these in imitation of the Vellālans. According to the account given at Orattanādu, the members of Ambalakāran families sit by hereditary right as Kāryastans or advisers to the headman in each village. One of these households is considered superior to the others, and one of its members is the headman (Ambalakāran) proper. The headmen of the panchayats of villages which adjoin meet to form a further panchayat to decide on matters common to them generally. In Kallan villages, the Kallan headman often decides disputes between members of other lower castes, and inflicts fines on the party at fault.”

In the Gazetteer, of the Madura district, it is recorded that “the organization of the Kilnād Kallans differs from that of their brethren beyond the hills. Among the former, an hereditary headman, called the Ambalakāran, rules in almost every village. He receives small fees at domestic ceremonies, is entitled to the first betel and nut, and settles caste disputes. Fines inflicted are credited to the caste fund. The western Kallans are under a more monarchial rule, an hereditary headman called Tirumala Pinnai Tēvan deciding most caste matters. He is said to get this hereditary name from the fact that his ancestor was appointed (with three co-adjutors) by King Tirumala Nāyakkan, and given many insignia of office including a state palanquin. If any one declines to abide by his decision, excommunication is pronounced by the ceremony of ‘placing the thorn,’ which consists in laying a thorny branch across the threshold of the recalcitrant party’s house, to signify that, for his contumacy, his property will go to ruin and be overrun with jungle. The removal of the thorn, and the restitution of the sinner to Kallan society can only be procured by abject apologies to Pinnai Tēvan.”

The usual title of the Kallans is Ambalakāran (president of an assembly), but some, like the Maravans and Agamudaiyans, style themselves Tēvan (god) or Sērvaikkāran (commander).