Kannur

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Violent politics, Clashes between CPM, R-S-S

186 murders 1960s-2016

Sudhakaran P, March 8, 2017: The Times of India

Kannur Has Witnessed 186 Murders In Clashes Between CPM & R-S-S Over The Past 50 Years

The culture of bloodshed in Kannur, which continues even today despite ritualistic political handshakes to give peace a chance, is probably as old as the folk traditions of the land, its myths and history . From the myths of theyyams that glorified the subaltern gods to the Vadakkanpattu (ballads) and the revolt against the British by Pazhassi Raja, there are plenty of stories where people shed blood with pride.

But in the age of democracy why is this place obsessed with martyrdom? Is it because a martyr is a political investment? From the murder of R-S-S leader Vadikkal Ramakrishnan in Thalassery in 1968 (considered to be the first political murder) to killing of E Santhosh (another R-S-S activist) in January 2017, nearly 186 people have been killed here over the past five decades.

The north Malabar region always had a tradition of violence right from the days of feudalism, said historian K K N Kurup. “If the reason is politics, why is it not there in other parts of India or Kerala? Why they practice this camouflage battle strategy here only?“ he asked. He felt that this was the continuation of a tribal character though their act of vendetta is political in nature. “If African tribes involve in fights to assert their racial supremacy, here it is for political supremacy. Both reflect the same attitude. I feel they have the element of the `suicidal fighter' in this age of democracy ,“ he said.

However, it is wrong to link the gory culture in politics with Vadakkanpattu, said kalaripayattu exponent P Meenakshi Amma. “The fights narrated in Vadakkanpattu had a basic element of ethics. In the political battlefield, bloodshed is mostly an act of vendetta. They get involved in it because they have no knowledge about the tradition of kalaripayattu and Vadakkanpattu,“ she said.

But this political violence cannot be isolated from the folk tradition of the place that often told the story of the lower-caste victims, said researcher T Sasidharan, who heads the political science department of Kannur S N College.He had exhaustively researched the history of political violence in Kannur and wrote a book titled `Radical Politics of Kannur'. “When we look at the socioeconomic aspect of the murders and violence in Kannur, it can be seen that nearly 65% of the martyrs, irrespective of politics, belong to the thiyya community. A majority of them are economically-backward,“ he said.

Though the murder of Ramakrishnan is considered to be the beginning of political murders in Kannur, the roots of political violence began with the emergence of Praja Socialist Party (PSP) in the 1950s under P R Kurup, he said. There were clashes between PSP and the Communist Party in Panur and with the disintegration of PSP in the late 60s, the violence took a new turn when its workers joined Jana Sangh.

Though political rivalry is said to the reason for the violence here, the political character is fast vanishing and `quotation culture' is making inroads, said K P Mohanan, a local political observer who has closely followed the culture of bloodshed in Kannur. Though murders have been an ongoing process, incidents such as the attack on CPM district secretary P Jayarajan on August 25, 1999 worsened the situation. This ultimately led to the murder of Yuva Morcha leader KT Jayakrishnan on December 1, 1999, and a spate of murders followed, he added.

“It is a fact that Kannur shows a tribal character when it comes to murder, and that is why if one person is killed, his political tribe target the rival elsewhere. But, the tragedy is that quite often the poor working class people coming home after their day's work are the victims,“ he said. Incidentally, while murders in the past took place in broad daylight, now it is committed at night and this has given rise to the impression that some `third parties' and quotation gangs without any political commitment have replaced the political warriors, claimed residents.

1960s-2021

Leena Gita Reghunath, March 3, 2022: The Times of India

From: Leena Gita Reghunath, March 3, 2022: The Times of India

Kannur’s modern history comes dipped in red. Pinarayi, a small town in Kannur, where the current CM of Kerala also hails from, is where the first meeting of the Communist Party of Kerala was held in 1939. The towns and villages around it are political hotbeds.

There is a saying in these parts that the cadre can tolerate insults aimed at their forefathers, but not at their party.

Kannur also has a lot of cultural significance within Kerala because of its unique ritual art forms of theyyam and thira, where the performers take on the role of deities, and the stories of valour and kodipaka, an intergenerational bloody feud, run through its folklore.

Generations of families here are also trained at kalaris, where they become proficient in weaponry and the martial art of Kalaripayattu, dedicating their mind, body and family in the fight for honour. Even today, weapons like vadival, which are otherwise found in kalaris or used for agricultural purposes like hacking coconuts, are used in political murders.

“There is also a caste angle to this,” points out Antony, “as most often it is the Thiyya families that are involved in these killings.”

Members of the Thiyya caste of Malabar, though classified as other backward class, and considered similar to Ezhavas in other parts of Kerala, have a comparatively higher ranking in Malabar, and mostly belong to landowning families.

“I have observed that sometimes those convicted in these political murders are distantly related to each other,” notes Antony. This is not unusual as those living in the interior villages of Kannur often find relations in common. Moreover, the killers are often known to the victims and are old classmates and neighbours.

No mercy

Until the 1990s, it was mostly toddy tappers and farm labourers who were given the task of executing political murders. But in recent years, these are being increasingly taken up by quotation gangs, essentially criminals for hire.

The early days of political murders also saw the use of crackers mostly to clear the site once a muder was committed. The 1990s saw the use of actual bombs, which are continued to be made in small villages dotting the district. This is why news of party workers blowing up their limbs and houses is not uncommon in Kannur. Political murders, however, are not just the domain of parties like CPM and BJP. In January, Dheeraj Rajendran, a Kannur resident and member of the SFI, the students’ wing of the CPM, was stabbed to death by members of KSU, the students’ wing of the Congress party at Government Engineering College, Idukki.

These retaliatory political murders also extend beyond Kannur as was seen in 2021 when SDPI state secretary KS Shan was murdered on December 18 in Mannancherry, Alappuzha district, by R S S activists. The very next day, BJP leader Ranjith Sreenivas was murdered in Alappuzha in retaliation by SDPI members.

“This is an example of the ‘quick-action militancy’ that SDPI is capable of,” points out Nidheesh J Villatt, a journalist based in Delhi, who has extensively researched these killings.

In fact, Vadikkal Ramakrishnan of the R S S is considered to be the “first political martyr of Kannur”. He was killed in April 1969 in Thalassery, in response to an attack on CPM leader Kodiyeri Balakrishnan.

Action, reaction

When the BJP came to power at the Centre in 2014, these murders began to grab national headlines. In 2016, Prime Minister Narendra Modi released Aahuti: The Untold Stories of Sacrifice in Kerala, which narrates the stories of R S S-BJP workers killed in political violence.

In 2018, journalist Ullekh NP’s book Kannur: Inside India’s Bloodiest Revenge Politics explored the lack of a political will to put an end to these battles and how “cosmetic investigations” by law enforcement agencies enable the culprits to get away.

“What has often shocked me is the element of hatred and animosity in these crimes,” says Antony. “They would hack a person and throw sand into the wounds, so that even if the doctors manage to stitch them up, these sand grains would remain lodged within, and the victim was left to a life of pain and suffering.”

Dileep Raj, a writer and professor at Kannur University, believes that these fights continue to be over capturing socially significant public spaces, like a local temple or public library. He also refutes the theories that the local culture and passions trigger these murders, which are “clearly blessed by the party authorities”.

“This violence is clearly a modern phenomenon,” Raj claims. “This system works because it is a profitable business for the political parties involved. The day it stops being profitable, these killings will stop.”

He also points out that there was a lull in the CPM’s planned murders following the much condemned killing of TP Chandrasekharan on May 2, 2012. The hacking of the powerful local leader, who had fallen out with the CPM and established the Revolutionary Marxist Party, remains one of the most chilling political killings of Kerala in which several communist activists were convicted.

“It shows that these parties do this because it suits them,” says Raj. “The more brutal the revenge, the deeper the wound is, the more loved the fallen man is, the bigger the martyrdom and its benefits for the party.”

Speaking to a news channel on February 23, TP’s widow and MLA KK Rema said that in Kerala, both the murdered and the murderers are equally glorified as heroes, and that combined with the protection awarded by parties to these criminals, ensure that these political crimes do not end. Most of the people found guilty in her husband’s murder, she claimed, are today out on parole and being protected by the party.

1999, 2020-22

Ullekh NP, February 25, 2022: The Times of India

- February 21, 2022: A CPI (M) worker was hacked to death by alleged R S S workers in Kannur following quarrels between the two camps over a festival at a local temple.

- April 6, 2021: Youth League activist Paral Mansoor, 22, was killed after he was attacked soon after the polling for assembly elections was over. The accused was a CPI (M) activist.

- November 2021: S Sanjith, an R S S worker, was hacked to death in Mambaram in Kannur district.

- In 2020, a 30-year-old political worker of the Social Democratic Party of India, the political arm of the pro-Muslim Popular Front of India, was hacked to death allegedly by R S S activists in front of his sisters. He was one of the seven accused in the murder of a 24-year-old ABVP activist and was out on bail.

- In 1999, Marxist leader P Jayarajan was attacked with bombs and machetes at his home in Kannur. He survived with the loss of a thumb and a disabled hand. Three years ago, BJP members raised a slogan at a rally: “Otta kayya Jayarajaa, matte kayyum kaanilla (one-handed Jayarajan, we will chop off the other hand, too).”

These are just some of the gruesome killings that mar an otherwise scenic spot on the Arabian Sea with beautiful beaches and mouth-watering cuisine.

The official data pegs the number of political murders in Kerala’s Kannur district at 125 between 1984 and 2018.

What’s worse? The gruesome nature of the political murders. They often involve what's locally called the ‘vadival’ - literally, a sword on a hilt, like a machete. Or involve slitting the throat with a surgical knife, the use of which requires training.

Historically, the district was known for cold-blooded killings between the Congress and the undivided Communist Party of India or CPI. In it, the former had the advantage of having the police on its side. And then others entered the fray in the 1960s, most notably the R S S, who acted at the behest of Mangalore-based beedi barons.

Efforts to establish lasting peace in Kannur — home to three of Kerala’s chief ministers, including the incumbent Pinarayi Vijayan — have been going on for a while. Vijayan enlisted the support of the spiritual guru Sri M, who is close to him and to some top R S S leaders, to initiate talks more than five years ago. But old wounds continue to fester and older habits refuse to die. The government clearly has a Herculean task ahead of itself, which must start with learning lessons from the past.

The book, Kannur: Inside India's Bloodiest Revenge Politics, looks into the history of the state to understand when the political violence started in the region, what were the triggers and who shaped the narrative. Here are some excerpts…

It is no surprise that communists found Kannur a fertile ground for launching peasant struggles. It had seen extreme concentration of land among the upper castes, much more than any other district in Kerala. In Malabar, most of the land was held by the Namboodiris in the southern parts and the Nairs in the north, though a section of rich Thiyyas did have large tracts in their possession as well. The majority of the poor lower castes were landless.

However, for a couple of decades after independence, the communists didn’t have the organisational and political wherewithal to resist the onslaught by the ruling classes. The peasant movements that would shape the political culture of Kannur and its adjoining areas began in response to agrarian crises and a massive shortage of food grain.

The repressive tactics invoked a deep craving among the Kannur comrades for avenging the humiliations, torture and murders; but they felt helpless in the face of the brute power of the new ruling class of so-called Gandhians and a police force that had been trained by the British… [But] until its split (in 1964), the Communist Party of India wasn’t the invariably vindictive, overly spiteful entity it later became towards the opposition, especially in the Thalassery region, which would later become the epicentre of the political clashes in Kannur over the decades.

Though there have often been cases of stand-offs between murderous Congress workers and the communists who were often at the receiving end as a party with inferior cadre strength, maintaining a perpetual combative posture had not been the case even in far more trying situations earlier. That changed in the 1960s when a new set of leaders came up. Prominent among them was M V Raghavan, who was born to an impoverished, notionally upper-caste family.

MVR never left Kerala and made a living doing odd jobs, including weaving and farming. He had joined the party in the 1960s, at a time titans (and some of the senior-most communist leaders in Kerala) such as A K Gopalan, A V Kunhambu, K P R Gopalan and C Kannan were at the helm of affairs in Kannur. C H Kanaran was the powerful state secretary when the party split in 1964 and the CPI(M) was formed. And within four years, MVR and a team of Young Turks captured the leadership of the CPI(M) in Kannur in perhaps the first-of- its-kind effort to dislodge any high-level official panel of the party.

In the late 1960s and ’70s, MVR wielded enormous power within his party after he had managed to side-line — some say with covert help of AK Gopalan – senior leaders from trade unions (such as C Kannan) and farmer organisations (such as A V Kunhambu), who were pivotal to the growth of the party in Kannur for more than three decades. In the run-up to the 1980s, many of his seniors and contemporaries who could have posed a threat to him either left the party, died or were killed, leaving him to deal mostly with yes-men and a small band of young rebels and old-timers. MVR brought to the fore a political culture that would have an impact on the CPI(M)’s Kannur unit for decades to come. Even as the party was growing organisationally, he never missed an opportunity to verbally assault his rivals in an obscene manner, and often incited his cadres against their opponents.

Party insiders say this constant display of aggressive masculinity was his way of ensuring his supremacy. Any dominance within the party of the intellectual kind would have diminished his appeal. Putting party cadres on a quasi-violent mode and on tenterhooks enhanced his persona as a belligerent leader with a halo around him. His street-fighting tactics, too, gave him an edge as he personally hurled abuse at the police at protest marches.

People close to him, like the former member of Rajya Sabha Pattiam Rajan, say that his rivals hated him for his guts and for the fact that he never let an attack on his cadres go unpunished. Rajan argues that such measures acted as a deterrent against attacks on the CPI(M) cadre.

Roguishly handsome with an irresistible personality, MVR, who had a hardscrabble childhood, clearly used his toughie image to the maximum extent within and outside his party. Some of his contemporaries tell me that he was intensely competitive even within the party, a trait that was back then mostly associated with careerist Congress leaders.

MVR was no democrat. On the contrary, he had a long history of purges and nepotism. He is known to have denigrated senior leaders, plotted their downfall, used his acolytes to publicly humiliate them, and had explored the immense possibilities of the craft of politically slaying an opponent within the Stalinist confines of his party, just as EMS himself often did.

[Today,] along the beach in Payyambalam are a crematorium and a graveyard filled with columns and tombs. It is an expansive compilation of the departed who’s who of the town. The graves on the left when you approach from the crematorium (it has yet to be electrified) are those of the Leftist men and fellow travellers while those on the right are those of leaders and workers of the Congress, the R S S and the BJP.

2016

The Times of India, May 16 2016

Rajesh Menon

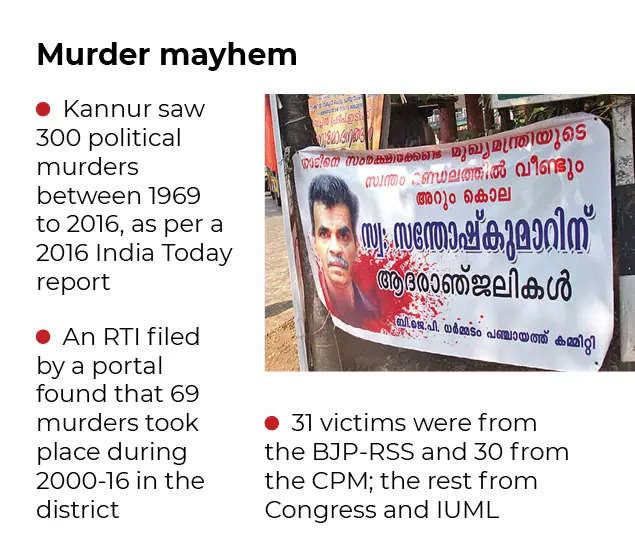

In Kannur, Kerala's political killing field, where the only religion they know is the party colour, it is always a feeling of when, rather than how, violence will start again. C Sadanandan Master, BJP's candidate from Koothuparamba lost both his legs in the political violence. Kannur's tale of blood and gore over ideologies began in the 1970s with bombs, swords, knives and axes. Since then close to 300 have been killed and over 500 injured.

It has mainly been a bloody game of red vs saffron. “It's always `our dead and maimed vs their dead and maimed,“ says a veteran journalist and political observer.

Mostly low-level party workers or supporters are targeted, the list drawn up randomly to quickly settle the score after every attack.

If local worker 32-year-old Biju of Kathiroor Panchayat survived two attacks, 32 cuts and slashes across his body and nearly a year of hospitalisation including at the Kozhikode Medical College, he believes it is “because of a miracle“. This was nine years ago [2009] and today Biju hobbles around, his left arm rendered useless, with the help of painkillers. His youth lost to violence, Biju has no regrets. “Those who attacked me have been thrown out by CPM from the party . I call this divine justice,“ he says.

CPM neta from Thalassery V K Suresh Babu, the 60-year-old retired headmaster of a local school, who survived an attempt to murder with 12 cuts on his body and whose `dying' declaration was recorded by a magistrate in 1999, says Kannur residents have be come used to the violence. “We're willing to die for the party. It comes from the heart and can't be taken away . But the supporters and sympathisers of either side bear the brunt,“ he says.