Kashida

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A backgrounder

As of 2024

Bilal Bahadur, TNN, Oct 8, 2024: The Times of India

From: Bilal Bahadur, TNN, Oct 8, 2024: The Times of India

Srinagar : The free market is a beast that won’t be shackled. It’s the reason the bottle of Worcestershire sauce in someone’s fridge is probably from Nagpur, your neighbour’s precious Persian rug was woven in Agra’s Old Vijay Nagar, and Assam’s gamosa used to be Surat’s money-spinning business.

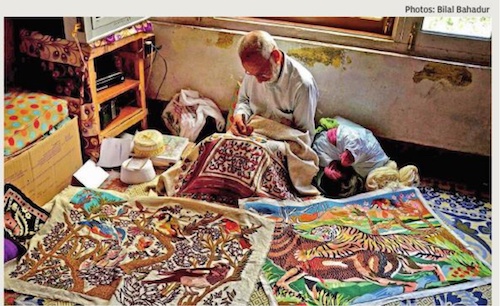

In J&K, master artisans Mehrajud-din Beigh and Noorullah have been fighting to save the centuries-old Kashmiri art of chain-stitch embroidery, Kashida, from the ravages of factory production at scale since long before GI tagging entered the protectionist discourse.

“My scariest thought is that kashidakari will vanish. You will still buy rugs with complex, traditional Kashida patterns, but they will all be machine-woven. That’s doing injustice to this great art form,” bemoans Beigh, 65.

Kashida embroidery dates back to the 15th century, flourishing under the patronage of Zain-ul-Abidin of the Shah Mir dynasty that presided over the Kashmir sultanate.

The primary tool artisans skilled in kashidakari use is a hooked needle called an aari. The process starts with sketching the design on the chosen fabric and then filling it with chain stitches using fine silk or wool threads. The design is a raised, textured surface that is visually intricate, creates a riot of colours, and is soft to the touch.

The late Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, who spent a lifetime promoting Indian handlooms and handicrafts, once described Kashida as “essentially a child of landscape and bountiful nature”.

“The inexhaustible display of colours, variegated birds, luscious fruits, majestic mountains, shimmering lakes – all find a place in Kashmir embroidery,” she wrote.

Blogger Mala Chandrashekhar, who writes extensively on art and culture, points out that artisans often use subtle colour variations within a single motif to create depth and dimension. Each motif and pattern holds significance. Chinar leaves symbolise the valley’s beauty, almond blossoms denote hope and renewal, and paisley represents fertility and abundance.

Beigh, a resident of Srinagar’s Chanpora, started learning the art of Kashida from an artisan in his neighbourhood when he was seven. For someone who’s spent over five decades as a practitioner of kashidakari, he still makes only about Rs 2,000 a month for three to four pieces.

While Beigh’s son chose to be a salesperson rather than carry forward his father’s legacy, the senior artisan remains eager to help keep the art form alive.

“If the govt assists, I will happily mentor whoever from the next generation is willing to learn,” he tells TOI. Noorullah, from Khwaja Bazar, is from a family of Kashida artisans, but his children – two daughters and a son – aren’t keen on continuing the tradition. “They are studying and would rather do something else. I don’t blame them,” he says. Although GI tagging of Kashida, for which the J&K administration applied in Jan 2023, could make a difference to the economics of the business, Beigh and Noorullah are worried that there might be few skilled artisans left to ply the trade in a few years.

“We need focused initiatives to promote this craft, including financial assistance, more market opportunities, a campaign to raise awareness about the cultural significance of chainstitch art, and seminars and workshops,” says Noorullah.

The years lost to militancy and spiralling input costs have also contributed to the dwindling of skilled artisans.

“There was a period when we had huge quantities of unsold stock because J&K was almost shut to the rest of the world. Now, the challenges include changing customer preferences and machine embroidery mimicking Kashida. All of this is intimidating for someone who’s not attached to our heritage as we are,” says Noorullah.

The one change that Beigh and Noorullah believe has the potential to turn the tide is the emergence of the discerning Indian customer, especially among the young. Demand for authentic traditional handicrafts and handlooms has been growing in recent years. GI tags for Kashida and Kashmiri crewel embroidery could be the game changer.