Khalique Ibrahim Khalique

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Khalique Ibrahim Khalique

Khalique Ibrahim Khalique

Documentary films and Pakistan

By Khalique Ibrahim Khalique

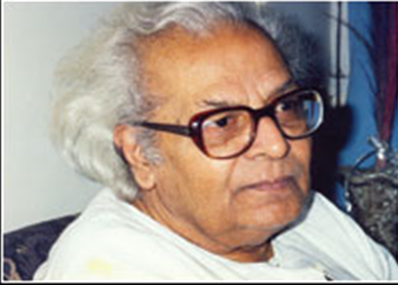

Writer and poet Khalique Ibrahim Khalique (1926-2006) was one of the founders of documentary filmmaking in Pakistan. Films directed and written by him received more than 20 merit awards internationally, the highest number for any Pakistani. His first death anniversary was observed yesterday.

THE protagonists of this art form believe that a film should not only depict reality in its most natural aspects but also creatively. The creative interpretation of reality is possible only when the truth of a thing is captured. And to grasp the truth of a thing one has to find out the elements that make it a living reality. A documentarian's camera must, therefore, expose the varying aspects of life in a way that brings out the dramatic elements of the most ordinary things.

Film exerts a tremendous subconscious influence. The dual physiological appeal of its pictorial movement synchronised with natural and symbolic sound is so strong and vehement that if made with sincerity and ingenuity it can stir the emotions of any audience. Taking full advantage of this cinematic appeal, a documentarian may utilise it for definite social purposes. Films were occasionally made after the documentary style since 1910, but full realisation of the demands of this new art form came in the 1920s. The First World War and its aftermath, particularly the worldwide recession enhanced the social consciousness of filmmakers in different countries. Robert Flaherty in America, Dziga Kertov in Russia, Alberto Cavalcanti in France, Walter Ruttmann in Germany and Andre Bunnel in Spain, John Grierson, Paul Rotha, and Basil Wright in England were outstanding among the pioneers of this art form.

John Grierson gave it the name ‘documentary’. The work of these and other pioneers gorgeously displayed cinema's tremendous capacity for getting around, for observing and selecting from life itself, for dramatisation of the living scene and the living theme, springing from the living present instead of synthetic fabrication of the studio.

The different artistic temperaments of these pioneers and the different environments in which they worked, imbued their documentaries with certain characteristics which crystallised into several traditions. Paul Rotha, in his book The Documentary Film, has dealt with four major traditions which had developed by the 1930s. According to his classification, there are naturalistic-romantic documentaries which usually show man's struggle against nature; realistic documentaries which depict everyday life in its multitudinous activities.

Rotha broadly divided the documentary in these major traditions. Otherwise there are specifically other types of films which also come from under the classification of 'documentary' such as, the record film, the scientific film, the cultural film, the medical film, the information film, the educational film and instructional film.

The popularity of documentary among the socially-conscious strata gave it the dimensions of a worldwide movement which gathered momentum during and after the Second World War. In 1947, prominent documentarians from all over the world met at Brussels and formed the World Union of Documentary. The historic declaration, issued by the union defined documentary as ‘the business of recording on celluloid any aspects of reality, interpreted either by factual shooting or by sincere and justifiable reconstruction, so as to appeal either to reason or emotion, for the purpose of stimulating the desire for and widening of human knowledge and understanding, and of truthfully posing problems and their solutions in spheres of economics, culture and human relations.’

…The first documentary to be made in Pakistan was The Birth of Pakistan (1947-48) which recorded the British withdrawal from the subcontinent, the first meeting of the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan and the Pakistan Day celebrations. Since then the Department of Films and Publications (DFP) has made documentaries on a variety of subjects of national interest.

The DFP has so far produced more than 300 documentary films, covering the entire panorama of developmental activities in the social, economic and cultural spheres.

Besides, the DFP issues from time to time ‘in-depth news specials’ and ‘news magazines’ of important and memorable events along with periodical regular newsreels. Informative and instructional 'shorts' or 'quickies', cartoon films for children based on Pakistan's folk tales have been made occasionally. The total number of these is around 1,500.

Important documentaries of the DFP have been shown in international film festivals at Ankara, Bangkok, Berlin, Cannes, Cardiff, Cleveland, Cork, Edinburgh, Frankfurt, Hawaii, Locarno, Madrid, Marseilles, Montreal, Moscow, Phnom Penh, Rome, San Francisco, Tashkent, Tehran, Tokyo, Vancouver and Venice, have bagged more than 50 awards, including ten awards received at national film festivals. A few of the outstanding documentaries awarded internationally include: One Acre of Land (1958), We Work Together (1961), Gandhara Art (1963), Pakistan Story (1966), Pakistan Sets its Course (1968) and Ghalib (1971).

…Outside of the DFP, Ahmad Bashir, Safdar Mir, A J Kardar, Mushtaq Gazdar, Aslam Azhar, Javed Jabber, Mohsin Shirazi, A K Kaisar, Obaidullah Baig, Nisar Mirza and a few others have made documentary films, and some of them remarkably good. But their total output along with the output of the Film Units of the Provincial Governments is not very encouraging. This situation is caused by a lack of interest and indifference on the part of the industrial and other non-governmental agencies which do not support Pakistani filmmakers. DFP has also been facing vicissitudes which have slackened the movement for promotion of documentary films in the country.

Documentary has proved its efficacy in the onerous task of informing, educating and motivating people to constructive action, and has also profoundly influenced the feature film. Ever since the box-office success of such documentary-oriented films as De Sica's Bicycle Thief and Rossellini's Paisa, it is exerting more and more influence on feature film in every country.

The need is to create conditions conductive to the promotion of documentary film production. This requires much larger quantum of state patronage and the support of industrial and commercial establishments.

Keeping in view special requirements of the medium, as a synthesis of art and technology, the DFP may be streamlined on strictly professional lines and its area of coverage broadened so as to enable it to stretch a focus on the nation’s efforts to stage a technological breakthrough.

— Excerpted from Documentary Film and the Productive Years of DFP (1982)

Khalique Ibrahim Khalique

October 15, 2006

AUTHOR: Sky blue was his favourite colour

By Harris Khalique

In Karachi, when the sun starts setting early in September, the heat returns after an August interlude. But September 29, 2006 was a somewhat pleasant day. The sun was enveloped in thin clouds and the smog was less dense than usual. It was the first Friday of the month of Ramazan and the thick vehicular traffic on M.A. Jinnah Road and its adjoining streets kept moving at a reasonable pace. This is the best you can expect in that part of the city. Hasan Zaidi was driving me home from AnklesariaHospital. Bilal Aqeel, Haris Gazdar and Asad Sayeed were in different cars. Rahat Saeed took my mother Hamra home. Mubin Mirza and Mazhar Jameel had just left us to join again in a couple of hours. We were all following a St John’s Ambulance carrying his body, escorted by my brother Tariq. Aslam Khwaja, Irfan Ahmad Khan and Bushra were waiting for us at Hasan Square. Shaboo Bhai went straight to the graveyard to organise the place of burial.

Body. “Body of a dead man is like a nail clipped from the finger. It is the mind and the work he leaves behind that matters. And mind and soul is perhaps the same thing.” I was a child and he told me that whenever we returned from a funeral, more to console me than to give out a statement. The idea of a nail clipped from the finger struck me when I, the older son, was asked to produce a copy of my national identity card to receive the body and the death certificate. Dr Sheeshpal and Dr Kashif were kind. They quickened the process to cut the red tape and let us take the body home soon. Earlier, all the hospital’s ICU took special care of him for two reasons. One, they were good professionals and two, Dr Nasir Mirza, the in charge, asked them to do so. Nasir is a good friend and so is Dr Sarwar Siddiqui, the consultant neurologist, his physician who decided to take him to Anklesaria. The run down hospital has an aberration, a state-of-the-art ICU. That is where he breathed his last. Virtually, breathed his last. For the final cause of his death was the inability to breathe properly. The body struggled, resisted, fought hard but eventually fatigued. His central mechanism was affected resulting in disorientation and difficulty in swallowing food and water. He was semi-conscious when shifted to hospital and I was in Islamabad. I came down and stayed around him until the time the copy of my identity card was stapled with the copy of his death certificate. He had given me this identity and the hospital wanted a proof for its record.

Identity. “I am a Muslim, I am a Hindu. I am a Shia, I am a Sunni. I am a Christian, I am a Buddhist. I think I am a Communist.” His was a strange sense of identity. He was not confused. He was very clear. He thought it was quite possible to be all of that at the same time. His dialectical materialism and a staunch belief in Marxist ideals coexisted in complete harmony with his deep respect for people, their faith and culture. He never said any prayers, fasted occasionally when young I am told, had no desire whatsoever for any pilgrimage and I do not recall him offering any rituals. But he respected all those who did, never ridiculed any one who practised a faith or performed a ritual. His being nonreligious was not worn on his sleeve. Politically, he was not a liberal but a socialist, a people’s man. Many years ago he would recite verses from the Holy Quran and pray for the safety of the traveller who was about to embark on a journey. That was how travellers were sent off in his family and he respected that tradition. With age, this habit died and perhaps succumbed to his ever-increasing rationality and reason. He never claimed to be an atheist nor called himself a believer. He revered the prophets and saw them as revolutionaries, specially the prophet of Islam. He was an ardent admirer of the words and deeds of Ali (AS) and Lord Krishna, quoting a couplet of Yagana’s on this count. Always mentioned Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti with great respect. But would seldom fail to blast the role organised religion has played in human history, the violence, the prejudice and the subservience of reason to primordial values. He can never be termed religious, superstitious or even theistic. And it remains equally hard to brand him otherwise. Doesn’t that sound confusing? It does. Not for him though. He was very clear. He was a pagan.

Pagan. “I am a pagan. Like Nehru was. I think it has to do with the roots. All is one and Islam finally achieved the unity of God. It is irrelevant to discuss His existence, form and shape. It doesn’t actually matter. We now need to achieve the unity of humankind. A just, egalitarian and peace loving human society.” Like many progressive writers of his generation, he saw socialism as the only option for humanity to realise its truest and deepest values. It was a tool for him and not a dogma. Pagans have no dogmas and they would accept and use anything that benefits them and their fellows, physically and spiritually. Pagans are inclusive but they have a strong sense of belonging to their own culture and their land.

Khalique Ibrahim Khalique passed away on September 29, 2006

Belonging. “I am from Lucknow. A Kashmiri from Lucknow. A Hindustani Musalman like Iqbal. Our forefathers converted to Islam, left Kashmir and settled in Lucknow. Now I am a Sindhi. A Sindhi by choice, not by birth or by compulsion. But I remain a part of the Indo-Persian civilisation, a Hindustani Musalman like Iqbal.” He identified strongly with Lahore, where he did his degree in English and Adeeb Fazil in Urdu, with Delhi, where he spent a year in Jamia Millia and had many friends, with Mumbai, where he learnt the skill of life. Karachi was his home base for half a century and anything worthwhile he did in cinema was either here in this city or while he intermittently spent time in Lahore. But he was a Lucknavi, through and through. He never returned to India. To him, it was a part of the same civilisation where he now lived. A changing civilisation, however, and the change never bothered him. He had no complains against the youth, the new trends or the changing landscapes of culture and art. Except for the etiquette and the table manners. While he enjoyed calling himself a Sindhi by choice and actually meant it, Lucknow and Mumbai throbbed with his heart, and the vale of Kashmir resounded in his imagination, his cherished personal history and in his bowl of saltish tea. He was born in Hyderabad Deccan and made himself a domicile from Hyderabad Sindh when his employer insisted on him producing one. Dhaka and the boat rides in the mouths of the Ganges could never be forgotten. Filming in Bengal had brought him many rewards too.

Films. “I don’t like these small screens. 35 mm is my medium. Documentary is more of a challenge because inanimate things and ideas are the protagonists.” He loved cinema. He was among the first four Pakistanis who introduced documentary filmmaking in this country. The other three are Agha Bashir, H.C. Haccum and Safdar Mir. All are now gone. He became the most prominent among them in filmmaking. The profession brought him little money but a lot of recognition in those years. His documentaries were screened internationally and won prizes at home and abroad. He guided many in low budget filmmaking and script writing. He continued directing films until 1980 and wrote a few scripts even after that. Then took to literary writing full time.

Writing. “Basically, I am a poet. But the critics and my friends would take time to recognise that. Maybe they never will. Sometimes it seems there is a conspiracy of silence as Jean Cocteau puts it. It is hard to accept a strong voice. My important things remain unnoticed at times like the long poems because Urdu readers despise erudition and serious thought. Also, it takes a lot of public relations. I am bad at that.” He was self effacing. He did chair many literary meetings or presented papers at seminars on people’s insistence but was generally shy. Films are screened but being a poet in Urdu tradition also requires the ability to stage yourself and promote your work through performances in mushairas, public gatherings and appearing on television. He couldn’t do that. He never compared his work with great poets but thought his work was better than many who are well known today. He was right. What brought him laurels in later age was not his poetry but his memoirs. In that book, Lucknow serves the purpose that Pind Dadan Khan served for Al-Beruni when he measured the diameter of the earth. His memoirs encompass the social, political, literary and cultural history of the entire subcontinent beginning from 1880s until 1953. His rich experience in journalism, translations, script writing and cinematography, all aid him in writing this exhaustive book. The second volume he promised could not be written. Initially, it was partly his health and partly the exhaustion after penning a mammoth first volume. Then he started slowing down. Writing became cumbersome. He resisted and did not want to give up on life. But health failed him.

Life. “Life has to end but I want to live as much as I could.” You lived as much as you could. You and I and many others wanted you to live more. When everyone including my mother had lost hope, I genuinely believed you would come back. For you had always recovered, always fought back, always stood your ground, always sided with and defended the weak. This time, your own body was weak and I was sure you would fight for it. You did. “The body is trying hard. Unconscious but resisting. Blood tests were remarkably good. Numbers on the monitor including oxygen saturation deteriorate but he comes back and they become perfect. Pulse volume is good. Only that he is breathing hard by using accessory muscles for too long. That is not good. He will be fatigued,” the doctors told me. Then for some time the muscles seemed a little relaxed while you were breathing and I was happy. The numbers on the monitor kept fluctuating and doctors were worried. I couldn’t stay in the ICU for too long and waited in the outer room, not for you to die but for you to recover. I was so sure. The doctor came out and told me there is a 10 per cent chance. He went inside again. I called Tariq, Bilal and Shaboo Bhai. I had sent a text message to some friends asking them to pray for you and wish you well. I didn’t know what else to do. My mother joined me in the outer room of the ICU. Hasan called me right after receiving my text message and while I was on the phone with him, Dr Sheeshpal came out to tell me that you had breathed your last. It was over.

Perhaps you didn’t know that a day before, I felt like touching your hands, your feet, your forehead and your cheeks while you lay unconscious with eyes half open. You were still there, not yet a nail clipped from the finger, and didn’t approve of what you were being put through. The tubes, the drips, the catheter and the oxygen mask. I could see that helplessness in your eyes but couldn’t do much. You would protest, pull the tubes out and throw the mask away if conscious. That is what you did a few days earlier in PatelHospital. But now you were weak and mostly unconscious. Your fingernails and toenails were not that long and I did not want them to be clipped. (— Written on the night of October 2, 2006)

Khalique Ibrahim Khalique (1926-2006) — a profile

Khalique Ibrahim Khalique was born into a clan of Kashmiri Brahmins who had converted to Islam and settled in Lucknow. The family practised Greek Medicine, established educational and literary institutions of renown and participated in the freedom movement.

Khalique received his early education in Lucknow and graduated from PunjabUniversity, Lahore. He began his film career in Mumbai and moved to Karachi in 1953.

He excelled as the pioneering documentary filmmaker of Pakistan. His films were exhibited world over including at Cannes, Paris, London, Berlin, Moscow, Leningrad (St Peter’s Burg), New York and Beijing during the 1960s and ’70s. He won more than 20 prizes including merit awards from international festivals, Tamgha-i-Imtiaz in 1969 and a Lifetime Achievement Award from Karafilm Festival in 2003. He was an acclaimed poet and writer of Marxist persuasions. His memoirs gained special recognition.

Major films: “Ghalib”, “Pakistan Story”, “Pathway to Prosperity”, “One Acre of Land”, “The Coconut Tree”, “Cultural Heritage of Pakistan”, “Architecture”, “Journey through Darkness”, “Buddha in Stone” and “Quaid-i-Azam” (banned under General Ziaul Haq).

Books: Manzilein Gard Ke Manand (Memoirs), Ujalon Ke Khwaab (Poetry), Pakistan Story (History), Kamyab Nakam (Short Stories), Aurat Mard Aur Dunya (Drama), Urdu Ghazal Ke Pachchees Saal (Criticism) and Chund Tahreerein (Criticism/Poetry selected by Rahat Saeed). — Compiled by Mushir Anwar and Zafar Masud