Khetri

Khetri, 1908

Head-quarters of the chiefship of the same name in Jaipur State, Rajputana, situated in 28 degree N. and 75 degree 47' E., about 80 miles north of Jaipur city. Population (1901), 8,537. The town is pic- turesquely situated in the midst of hills, and is difficult of access, there being only one cart-road and two or three bridle-paths into the valley in which it stands. It is commanded by a fort of some strength on the summit of a hill 2,337 feet above sea-level. In the town the Raja. maintains an Anglo-vernacular high school attended by 66 boys, a Hindi school attended by 112 boys, and a hospital with accom- modation for 6 in-patients. There are also 5 indigenous schools, and a combined post and telegraph office. In the immediate neighbour- hood are valuable copper-mines, which, about 1854, yielded an income of Rs. 30,000, but which, owing to the absence of proper appliances for keeping down the water and a scarcity of fuel, have not been worked for many years. Nickel and cobalt have been found ; but these minerals are quarried principally at Babai, about 7 miles to the south, the ore being extensively used for enamelling and exported for this purpose to Jaipur, Delhi, and other places. The chiefship, which lies partly in the Shekhawati and partly in the Torawati nizdmat, consists of 3 towns — Khetri, Chi raw a, and Kot Putli — and 255 villages; and the popu- lation in 1901 was 131,913, Hindus forming nearly 92 per cent, and Musalmans 8 per cent. In addition, the Raja has a share in 26 villages not enumerated above, and possesses half of the town of Sin- ghana. The town and pargana of Kot Putli are held as a free grant from the British Government, while for the rest of his territory the Raja pays to the Jaipur Darbar a tribute of Rs. 73,780. The normal income of the estate is about 5-3 lakhs, and the expenditure 3-5 lakhs.

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

A lost legacy

Rohit Parihar

January 23, 2015

The princely state that once helped Swami Vivekananda and the Nehrus is witnessing its heritage being torn apart

About 170 km southwest of Delhi and 150-odd km slightly northeast of Jaipur lies the erstwhile princely state of Khetri. Not many would have heard of it. Though picturesque, it is by no means a state of Rajput valour that has become history, fable and folklore rolled into one.

But it is Khetri that one Narendranath Dutta, then Swami Bibidishanand, looked towards each time he needed succour-monetary, as also to discuss his ideas through lengthy letters to its ruler of the time, Ajit Singh Bahadur, a disciple of the swami, who suggested the name Vivekananda. And it is Khetri Vivekananda returned to after delivering his famous address at the first Parliament of the World's Religions in Chicago, in September 1893.

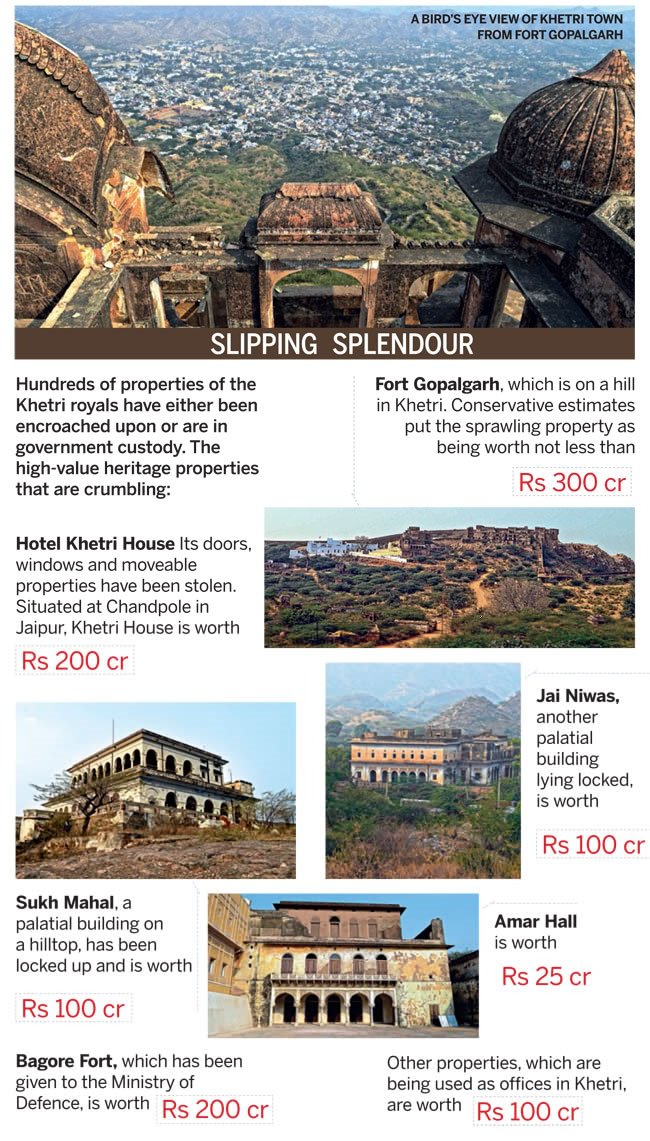

Khetri is also where an infant Motilal Nehru was taken to-by his elder brother Nandlal, initially a teacher there before rising to become the diwan to Fateh Singh, the then king. And it is Khetri where Nandlal-who later left for Agra before eventually settling down in Allahabad to practise as a lawyer, a profession carried forward by younger brother Motilal and the latter's son, Jawaharlal-had his little tryst with notoriety back in 1870. As the diwan, Nandlal concealed news of Fateh Singh's death and had Ajit Singh, then nine, adopted from nearby Alsisar as the heir. Nearly 150 years on, Khetri is still witnessing a battle of succession, and litigation, even as properties, estimated at more than Rs.2,000 crore-including a three-star heritage hotel, Khetri House in Jaipur, and Fort Gopalgarh, the citadel on a hilltop in the town-stand derelict (see box for list of royal properties). All in the state government's custody after Khetri's last ruler, Rai Bahadur Sardar Singh, died in 1987. Divorced, Sardar Singh died without a child, making the Rajasthan government invoke the Rajasthan Escheats Regulation Act-a law formulated in 1956 but rarely used-and seize all properties for want of a successor. A legal battle has been going on ever since. Between Khetri Trust, created as per Singh's will, which, to quote from the trust's website, bequeathed all his properties to it to promote education and research; his cognates (or relatives) in the absence of a legal heir; and the state.

Those claiming proximity to the princely state, however, have had little luck in the courtrooms. In 2012, the Delhi High Court delivered a blow to the Khetri Trust, ruling against its 1987 petition that sought all royal properties from the government. Ruling on the petition, heard by 30 different judges over 25 years, in the case of probate (or officially validating) Sardar Singh's 1985 will, the court said it doubted authenticity of the will. The trust's appeal against the verdict has since been admitted by a division bench, where it may take years before a ruling comes about.

In November 2012, the Rajasthan High Court dismissed a petition by Gaj Singh of Alsisar, who claimed to be Sardar Singh's agnate, or heir, by adoption-he even claimed to have performed the customary 'pag dastur' (a ritual naming legal heir) in April 1987, after the latter's death. But a double bench of HC modified it the following year, acting on which Jaipur Collector Krishan Kunal issued notices seeking claims of legal heirs to Khetri properties in July 2014.

The litany of litigations did not spare even the Ramakrishna Ashram, which was given a palatial building and other facilities by Sardar Singh in 1958 in memory of his grandfather, Ajit Singh Bahadur, and Swami Vivekananda to set up the ashram's first chapter in Rajasthan. Last June, Khetri Trust lodged an FIR against the Ramakrishna Mission's Secretary, Swami Atmanisthanand, accusing him of dislodging its office there. The room, along with its belongings, was later restored to the trust.

But even as the litigations show no sign of an end, Gaj Singh says he would not mind if Khetri's royal properties go to the trust-"But I would stake my claim if other cognates, or the government, claim ownership," he stresses. The trustees, though, are yet to come out of the post-verdict shock.

"The court took a long time deciding probate, and kept the judgment reserved for two years. Yet, it ignored the fact that trustees, who are not permanent, would get nothing except using the properties to promote education and research," says Managing Trustee Prithvi Raj Singh, pointing out that there's no gain-financial or otherwise-in the case for them. The problem aggravates, he says, in the absence of an inventory of different movable properties owned by the erstwhile royal family. Barring, of course, Jaipur's Khetri House, which has lost most of its doors and windows, along with its sheen and pride, to apathy.

Trustees have for long complained to the government that most moveable items appear to have been stolen, but in vain. A member of an erstwhile royal family told India Ttoday that he was even approached to buy a prized sword of the Khetri royalty a few years ago.

Government officials offer the excuse that no budget has been allocated for maintenance since the case is sub judice. But it does not take experts to notice that a magnificent fort like Gopalgarh in Khetri is literally falling apart due to a lack of maintenance-the occasional visitors vandalise its paintings, sculptures and mirror work; graffiti has taken over the walls; while many have blackened with people burning wood to cook meals in what should be a heritage property.

Khetri House, for instance,has been sold and resold through forged deeds-once even through a public advertisement by a Maharastra-based businessman and politician who claimed to deal in disputed properties. The irony being, the property is officially in government custody.

Tejbir Singh, editor of the magazine Seminar and a former trustee, says he was manhandled and harassed with FIRs by claimants who later got arrested on forgery charges. "It was a mess; encroachers took over properties and we were slapped with FIRs," Tejbir Singh says, "so I decided to pull out." Many other old-timers did the same.

The present set of trustees-Gaj Singh, the erstwhile maharaja of Jodhpur, Additional Director-General of Police Ajit Singh Shekhawat, and Prithvi Raj Singh-may be relatively more influential in the state, but even they are helpless in the face of the enormity of the task at hand. More so, since they have no official jurisdiction over the properties. Gaj Singh says they have lodged 10 FIRs against encroachers and fake buyers and sellers, and that only the trust can take care of the properties and use them for promoting education.

But on ground zero, faced with nonchalance, confusion, shenanigans and endless litigations, Khetri, which had lost 2,000 of its 14,000 soldiers who went to fight in World War I, is now battling to save a crumbling royal heritage.