Khyber-Pakhtunwa (North-West Frontier Province): The region

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Khyber-Pakhtunwa (North-West Frontier Province): 1

April 13, 2008

ARTICLES: Beautiful Indeed

In some places sheets of yellow flowers bloomed in plots; in others sheets of red (arghwani) flowers, in some red and yellow bloomed together. We sat on a mound near the camp to enjoy the site. There were flowers on all sides of the mound, yellow here, red there, as if arranged regularly to form a sextuple. On two sides there were fewer flowers but as far as the eye reached, flowers were in bloom. In spring near Peshawar, the fields of flowers are very beautiful indeed.

— Emperor Babar

When Babar first set eyes on the valley of Peshawar, he echoed the words of the Chinese traveller Hiuen Tsang who began his pilgrimage to the land of Gandhara in 629AD. Describing the land and the people, Hiuen Tsang said: ‘The country is rich with cereals, and produces a variety of flowers and fruits; it abounds also in sugarcane, from the juice of which they prepare ‘solid sugar’… The disposition of the people is timid and soft; they love literature; most of them belong to heretical schools; a few believe in the true law. From old time till now this border-land of India has produced many authors of Shastras… There are about 1,000 Sangharamas (monasteries) which are deserted and in ruins. They are filled with wild shrubs and solitary to the last degree. The Stupas are mostly decayed. The heretical temples, to the number of about 100, are occupied pell-mell by heretics…’

Fourteen centuries later, M. Athar Tahir describes this ancient land as one of the most legendary places on earth. In the first chapter of his well produced and competently researched book, Frontier Facets, he describes the Frontier in the following words: ‘In contrast to other provinces of Pakistan, this is a province where each season casts its own spell. If spring is fragrant, summer is warm, even hot, in the valleys, and invigoratingly cool on the mountain slopes. Autumn turns trees from russet to brilliant scarlet and yellow, and winter ushers in freezing winds and snow. Through the ages this land has enjoyed a unique position and character.’

This aptly-titled book concerns itself not just with the terrain and the creatures which live upon it, but is actually a scholarly work made accessible to the ordinary reader through the use of simple and lucid text and the most stunning photographs, most of which have been taken by the author himself. At this point in our troubled political history, when the province is marked by the blood of countless young and old men, women and children killed in a war not necessarily of their own making, it is an extremely important work which traces the history of the region from the earliest written record chronicled by the Greek geographer Hecataeus and the historian Herodotus, as well as the campaigns of Alexander. Archaeological records indicate that life existed here since Paleolithic times and evidence of tools, blade flakes and scrapers having been found in the Sanghao Cave, Mardan. In Bannu district, evidence exists of a culture which flourished between 3500 and 3000BC. The region was also home to the Harappa Culture (2700-2000BC), remains having been discovered at Maru, Dera Ismail Khan.

Tahir draws a historical outline which moves onto the migration of the Aryans into the region between 1800-1200BC. The region and people are mentioned in the scriptures of the Aryans, in particular the Mahabharata and the Rg Veda. In the sixth century BC, Darius the Persian sent a Greek seaman to explore the course of the Indus, brining the region under his empire. In 331 BC that empire was conquered by Alexander the Macedonian, but not before meeting fierce resistance from the Kamboja clans, the Aspasios of Kunar, the Guraieans of the Panjkora valley and the Assakenois of the Swat and Buner valleys.

The theme of popular resistance by the people of the Frontier against the invader runs throughout the picture which Tahir paints with masterly strokes. Moving on to the establishment of the Kushan Empire, Tahir treats us to wonderful visuals of stucco heads of the Buddha, as well as photographs of the seated and standing Buddha, followed by the masterpiece of stone sculpture called ‘Fasting Siddhartha’. He traces the contribution of the greatest Kushan ruler, Kanishka, to the Gandhara civilisation which flourished in the region, with the first capital of the empire being founded at what is today Charsadda.

The author pays painstaking attention to historical movements of invaders and conquerors in the Frontier, dwelling in detail on the British colonialists, and in doing so weaves layers of meaning into the fabric which is today the North-West Frontier Province, beleaguered by a new wave of would-be conquers who wish to deny the rich history of their homeland. In a way, this book is not just a tribute to the sons of the Frontier, including those who conquered it and made it their home, learning its many languages, tasting its waters, singing its music. It is also a work which enables one to understand a complex region which has become the focus of local and global attention in recent years.

Commissioned by a former Chief Secretary of the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (old NWFP), Shakil Durrani, this book could not have come at a better time, when we all need a better understanding of the land which has given us Ashoka’s message of peace and harmony and which is now scarred by hostility and at risk of being buried by obscurantism. In a chapter titled ‘Guardians of the Frontier’, Tahir writes about the British colonialist policy of ‘Butcher and Bolt’. ‘This policy consisted of punitive expeditions; killing men of the offending tribe, burning down their villages, destroying long standing crops on terraced fields an d then withdrawing. During the first decades of the 20th century even aircrafts of the Royal Air Force were inducted to bomb villages. First white leaflets of warning were dropped. The day before the bombardment, red leaflets were dropped. Then the RAF… went into action.’

It took Athar Tahir four years to gather the information, photographic material, paintings, personal histories, historical facts, political processes, legends, myths, and poetry of the Frontier region. He undertook this gigantic task while serving in various capacities as a civil servant who expresses himself best as a poet. Through Frontier Facets, he has given us another kind of poetry, one which sings of the tenacity of a people who still dare to celebrate despite the pall of gloom thrust upon the region by the doctrinaire of self-professed saviours. Beautifully composed and designed, the book forces one to believe once again in the words of Kushhal Khan Khattak:

From whence hath the spring again returned unto us,

Which hath made the country round a garden of flowers?

This coffee-table book explores the history and culture of the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan

Khyber-Pakhtunwa (North-West Frontier Province): 2

April 13, 2008

Magic mountains

By M. Athar Tahi

From whence hath the spring again returned unto us,

Which hath made the country round a garden of flowers?

There are the anemone and sweet basil, the lily and thyme;

The jasmine and white rose, the narcissus and pomegranate blossom.

The wild flowers of spring are manifold, and of every hue;

But the darktulip, above them all, predominateth.

The maidens place nosegays of flowers in their bosoms;

The youths, too, fasten bouquets of them in their turbans.

SO sings Khushhal Khan Khattak, the foremost poet of Pushto. These lines from ‘An Ode to Spring’ celebrate the colours and fecundity of his land. His other poems commemorate the wilder terrains of the Frontier, the tenacity, the valour and the joi de vivre of the Pathan, the Pakhtoon, a hardy, handsome people.

In contrast to other provinces of Pakistan, this is a province where each season casts its own spell. If spring is fragrant, summer is warm, even hot, in the valleys and invigoratingly cool on the mountain-slopes. Autumn turns trees, from russet to brilliant scarlet and yellow, and winter ushers in freezing winds and snow. Through the ages this land has enjoyed a unique position and character.

The province is surrounded by the Gilgit Agency to the north, Punjab to its south, Azad Kashmir to its east and Federally Administrated Tribal Areas to its west. It stretches along the Indus from Dera Ismail Khan bordering Baluchistan in the south, to the most northerly boundary with Afghanistan. The magic mountain ranges of the Hindu Kush to the north and north-west the Karakorum or the ‘Small Black Rocks’ to the north and north-east and the Himalayas or the ‘Home of the Snow’ to the east accord the land a dramatic backdrop. Fertile narrow strips along the Indus, desert in the south, lush and wooded hills, many deeply indented valleys, terraced hill-sides, tropical and sub-tropical forests, barren and rocky regions, all have contributed to make this province, most challenging and endearing.

Beyond Peshawar lies the narrow gorge of the Khyber Pass leading westward into Afghanistan. South of the Pass lies Tirah bordered by the Safed Koh Mountains. The hills of Waziristan are for the most part barren and treeless except some high ranges such as Shawal and Pir Ghal which have forests. Here the valleys are broader and fertile, merging into the plains. The Wazir hills rise to the Sulaiman Range, whose highest point is Takht-i-Suleiman or the ‘Throne of Solomon’. This range forms a barrier between the Frontier and Balochistan provinces.

The region between the Afghan border and some of the remoter districts still preserves pristine wilderness. Here the hills often rise into ranges of great height and the valleys become narrow. Between the Hindu Kush and the Peshawar Valley are the territories of Dir, Swat and Chitral. The last is the most northerly and a region of deep valleys and lofty ranges. To the south lie the wooded hills of Dir and Bajaur and the fertile valleys through which Punjkora and Swat Rivers flow. The snow-clad mountains of the uplands lift spirits towards an expansive dimension. Not surprisingly some of the earliest sacred Sanskrit texts were written in this province, and are imbued with a spirit of awe and reverence that such massive peaks evoke.

The Kaghan Valley with the famed mountain-lake, Saif ul-Muluk, is linked to the former Hunza State through the Babusar Pass. The Nawagai Pass links Dir to Afghanistan. Lalu Sarpat Lake near Babusar Pass and Dodi Sarpat Lake are between 4,000m to 5,000m high. Accessible from the Frontier, near the border at Chitral, is the 3.1 km wide Karumbar Lake. Surrounded by the Hindu Kush, Southern Pamir and Karakorum, it is one of the highest ‘biologically active wetlands on earth’. It thaws during May to September and hosts ‘a spectrum of migratory bird species on their annual North/South journeys’.

The province is criss-crossed by several rivers that churn their course to the plains of South Asia and to the sea. All, except the Kunhar River drain into the Indus. The snow-fed Kunhar, rich with trout, rushes through the Kaghan Valley and disgorges into the Jhelum River. The Kabul and Swat Rivers drain Kohistan, Swat, Dir, Chitral, Tirah and Peshawar districts. The Kurram River passes through the fertile Kurram Valley and the lower Wazir Hills to Bannu. Three miles below Lakki it is joined by the Tochi or Gambila River which drains northern Waziristan. The Indus forms the eastern border of the Dera Ismail Khan district. Near Attock it meets the Kabul River in a spectacular blue and muddy-brown embrace.

Within a radius of 65 miles from Gilgit are eight peaks over 24,000 ft, including Rakaposhi and the beautiful killer mountain, Nanga Parbat. Nowhere else in the world are there so many lofty peaks, deep valleys and long glaciers.

With such a vast geographic and altitudinal spread, the Frontier has five distinct ecological zones and is home to rich fauna and flora. Some of the flora Khushhal Khan Khattak has commemorated in his poetic corpus, but the variety is large. It ranges from shrubs of arid areas to lush forests rich with herbs, from alpine to coniferous and deciduous species such as blue pine, fir, deodar, evergreen spruce, juniper and oak, chinar, maple, walnut.

The region between the Afghan border and some of the remoter districts still preserves pristine wilderness. Here the hills often rise into ranges of great height and the valleys become narrow.

One important internationally recognised migration route occurs in Pakistan and straddles the province. The Central Indus Flyway enters the Frontier at Dera Ismail Khan and its branches pass through Chitral towards Afghanistan and over the Wakhan Corridor with Tajikistan. As such the Frontier is both home to, and staging area for, many migratory water and dry land birds such as the houbara bustard, cranes, sandplovers, hawks and falcons.

The National Park at Mount Shaikh Budeen provides the necessary natural conditions to assist in the migration. Some other natural reserve areas are the Mandra Kalan to Ramak covering 100 sq miles, Saif ul-Muluk Lake and Chitral Gol National Park on the Chitral River. The last, the private shikar gah or hunting preserve of the Mehtars of Chitral down the centuries, is a popular site for the sighting of hawks and falcons. Most sightings of snow leopards are also reported in this area during winter.

Among the regular winter migrants passing mainly down the Indus and entering by the Safed Koh Range and Kurram Valley are the Common and the Demoiselle cranes. The third species, the rarer Siberian crane also uses the flyway enroute to wintering grounds in north India. Of the three the Demoiselle, locally known as Koonj, is the most popular with the people. Its white down-curving ear tuft, pale bluegrey body and elegant carriage make it a coveted pet in Frontier households. These cranes migrate from central Russia and on their passage through the Kurram area are usually captured at night by Wazir tribesmen of the Bannu district. They are ensnared with saya, a local device with a 30 ft long twine and a lead weight. This is flung at low flying birds which are attracted by the sight and sound of caged birds. The Koonj is a symbol of social status and also prized as a good guard for it becomes noisy and aggressive when strangers intrude.

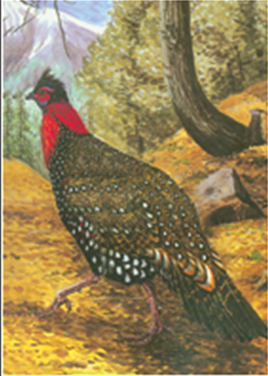

Of the many pheasants found in the Frontier, the Western Horned Tragopan pheasant is the rarest of all. The elusive brightly-coloured pheasant frequents precipitous and moderately steep mountain-slopes in the oak and coniferous forests of deodar-blue pine in the Kohistan district, up to the treeline at 12,000 ft It is occasionally found in similar habitat in the Kaghan Valley. To preserve and propagate pheasants, a breeding station has been established at Dhodial near Mansehra. Chakors and the black and gray partridges are popular pets, because of their sweet sounds. They are also believed to repel evil. An annual singing contest is held in Peshawar, when hundreds of chakors are brought to chirp their best. The chakor’s call characteristically contributes to the ambience of the alpine part of the Frontier, and is long remembered.

Excerpted with permission from

Frontier Facets

Tana Bana, Lahore & London

Available with National Book Foundation, Islamabad

164pp. Rs3,000

A bureaucrat by profession, M. Athar Tahir is the editor of the forthcoming Oxford Companion to Pakistani Art. An elected Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain, his prize-winning works include Pakistan Colours and Calligraphy and Calligraph Art