Kotah State, 1908

Contents |

Kotah State, 1908

State in the south-east of Rajputana, lying between 24 degree 7' and 25 degree 51' N. and 75 degree 37' and 77 degree 26" E., with an area of about 5,684 square miles. It is bounded on the north by Jaipur and the Aligarh district of Tonk ; on the west by Bundi and Udaipur ; on the south-west by the Rampura-Bhanpura district of Indore, Jhalawar, and the Agar tahsil of Gwalior ; on the south by Khilchipur and Rajgarh ; and on the east by Gwalior and the Chhabra district of Tonk. In shape the State is something like a cross, with a length from north to south of about 115 miles, and a greatest breadth of about no miles. The country slopes gently northwards from the high table-land of Malwa, and is drained by the Chambal and its tributaries, all flowing in a northerly or north-easterly direction. The Mukandwara range of hills (1,400 to 1,600 feet above sea-level), running across the southern portion of the State from north-west to south-east, is an important feature in the landscape. It has a curious double formation of two separate ridges parallel at a distance sometimes of more than a mile, the interval being filled with dense jungle or in some parts with cultivated lands. The range takes its name from the famous pass in which Colonel Monson's rear-guard was cut off by Holkar in 1804. It is for the most part covered with stunted trees and thick under- growth, and contains several extensive game preserves. There are hills (over 1,500 feet above the sea) near Indargarh in the north, and also in the eastern district of Shahabad, where is found the highest point in the State (1,800 feet). The principal rivers are the Chambal, Kali Sind, and Parbati. The Chambal enters Kotah on the west not far from Bhainsrorgarh, and for the greater part of its course forms the boundary, first with Bundi on the west and next with Jaipur on the north. At Kotah city it is, at all seasons, a deep and wide stream which must be crossed either by a pontoon-bridge, removed in the rainy season because of the high and sudden floods to which the river is subject, or by ferry ; and very occasionally communication between its banks is interrupted for days together, as no boat could live in the turbulent rapids. Ferries are maintained at several other places. The Kali Sind enters the State in the south, forms for about 35 miles the boundary between Kotah on the one side and Gwalior, Indore, and Jhalawar on the other, and, on being joined by the Ahu, forces its way through the Mukandwara hills, and flows almost due north till it joins the Chambal near the village of Piparda. The Parbati is also a tributary of the Chambal. Its length within Kotah limits is about 40 miles, but for another 47 or 48 miles it separates the State from the Chhabra district of Tonk and from Gwalior. It is dammed near the village of Atru, where it is joined by the Andherl, and the waters thus impounded are conveyed by canals to about 40 villages and irrigate 6,000 to 7,000 acres. Other important streams, all subject to heavy floods in the rainy season, are the Parwan and Ujar, tributaries of the Kali Sind, the Sukri, Banganga, and Kul, tributaries of the Parbati, and the Kunu in the Shahabad district.

The northern portion of the State is covered by the alluvium of the Chambal valley, but at Kotah city Upper Vindhyan sandstones are exposed and extend over the country to the south. The wild animals include the tiger, leopard, hunting leopard or cheetah, black bear, hyena, wolf, wild dog, &c. ; also sambar (Cervus unicolor), chital {Cervus axis), nilgai {Boselaphus tragocamelus), ante- lope, and ' ravine deer ' or gazelle. The usual small game abound ; and the rivers contain mahseer (Barbus tor), rohn {Labeo rohita), lanchi, gunch, and other fish.

From November to February the climate is pleasant ; in March it begins to get hot, and by the middle of June it is extremely sultry. The rains usually break during the first half of July, and from then till the middle of October the climate is relaxing and very malarious. The average mean temperature at the capital is about 82 . In 1905 the maximum temperature was 115 in May, and the minimum 49 in December.

The rainfall varies considerably in the different districts. The annual average for the whole State is about 31 inches, while that for Kotah city (since 1880) is between 28 and 29 inches, of which about 19 inches are received in July and August and about 7 in June and September. In the districts, the fall varies from about 25 inches at Indargarh in the north and Mandana in the west, to 37 at Baran in the centre, and to over 40 at Shahabad in the east and at several places in the south. The heaviest rainfall recorded in any one year exceeded 71 inches at Ratlai in the south in 1900, and the lowest was 14! inches at Mandana in 1899.

History

The chiefs of Kotah belong to the Hara sept of the great clan of Chauhan Rajputs, and the early history of their house is, till the beginning of the seventeenth century, identical with that of the Bundi family from which they are an offshoot. Rao Dewa was chief of Bundi about 1342, and his grandson, Jet Singh, first extended the Hara name east of the Chambal. He took the place now known as Kotah city from some Bhils of a community called Koteah, and his descendants held it and the surrounding country for about five generations till dispossessed by Rao Suraj Mai of Bundi about 1530. At the beginning of the seventeenth century Ratan Singh was Rao Raja of Bundi, and is said to have given his second son, Madho Singh, the town of Kotah and its dependencies as a jag'ir. Subsequently he and this same son joined the imperial army at Burhanpur at the time when Khurram was threatening rebellion against his father, Jahanglr ; and for services then rendered Ratan Singh obtained the governorship of Burhanpur, while Madho Singh received Kotah and its 360 townships, yielding 2 lakhs of revenue, to be held by him and his heirs direct of the crown, a grant sub- sequently confirmed, it is said, by Shah Jahan. Thus, about 1625, Kotah came into existence as a separate State, and its first chief, Madho Singh, assumed the title of Raja. He was followed by his eldest son, Mukand Singh, who, with his four brothers, fought gallantly at the battle of Fatehabad near Ujjain in 1658 against Aurangzeb. In this engagement all the brothers were killed except the youngest, Kishor Singh, who, though desperately wounded, eventually recovered. The third and fourth chiefs of Kotah were Jagat Singh (1658-70), who served in the Deccan and died without issue, and Prem (or Pern) Singh, who ruled for six months, when he was deposed for incompetence. Then came three chiefs, all of whom lost their lives in battle. Kishor Singh I, who ruled from 1670 to 1686, was one of the most conspicuous of Aurangzeb's commanders in the South, distinguished himself at Bijapur, and was killed at the siege of Arcot. His son, Ram Singh I, in the struggle for power between Aurangzeb's sons, Shah Alam Bahadur Shah and Azam Shah, espoused the cause of the latter and fell in the battle fought at Jajau in 1707. Lastly, Bhim Singh was killed in 1720 while opposing Nizam-ul-Mulk in his advance upon the Deccan. Bhlm Singh was the first Kotah chief to bear the title of Maharao, and, by favouring the cause of the Saiyid brothers, he obtained the dignity of panj hazdri or leadership of 5,000 ; he also considerably extended his territories, acquiring, among other places, Gagraun fort, Baran, Mangrol, Manohar Thana, and Shergarh. He was succeeded by his sons, Arjun Singh, who died without issue in 1724, and Durjan Sal, who ruled for thirty-two years, successfully resisted a siege by the Jaipur chief in 1744, and added several tracts to his dominions. Then came Ajit Singh (1756—9) and Chhatarsal I (1759-66). In the time of the latter (1 761) the State was again invaded by the Jaipur chief, with the object of forcing the Haras to acknowledge themselves tributaries. An encounter took place at Bhatwara (near Mangrol), when the Jaipur army, though numerically superior, was routed with great slaughter. In this battle the youthful Faujdar, Zalim Singh (see Jhalawar State), who after- wards as regent shaped the destinies of Kotah for many years, first distinguished himself. Maharao Chhatarsal was succeeded by his brother Guman Singh (1766-71), and shortly afterwards the southern portions of the State were invaded by the Marathas. Zalim Singh, who had for a time been out of favour, again came to the rescue and by a payment of 6 lakhs induced the Marathas to withdraw.

Guman Singh left a son, Umed Singh I (1771-1819); but through- out this period the real ruler was Zalim Singh, and but for his talents the State would have been ruined and dismembered. As Tod has put it : — 'When naught but revolution and rapine stalked through the land, when State after State was crumbling into dust or sinking into the abyss of ruin, he guided the vessel entrusted to his care safely through all dangers, adding yearly to her riches, until he placed her in security under the protection of Britain.' Zalim Singh was celebrated for justice and good faith ; his word was as the bond or oath of others, and few negotiations during the years from 1805 to 181 7, the period of anarchy in Rajputana, were contracted between chiefs without his guarantee. For the first time in the history of the State a settled form of government was introduced, an army formed, and European methods of arming and drilling were adopted. A new system of land revenue assessment was initiated, and the country was gradually restored to prosperity. In 181 7 a treaty was made through Zalim Singh by which Kotah came under British pro- tection; the tribute formerly paid to the Marathas was made payable to the British Government, and the Maharao was to furnish troops according to his means when required. A supplementary article (dated February, 1818) vested the administration in Zalim Singh and his heirs in regular succession and perpetuity, the principality being continued to the descendants of Maharao Umed Singh. Up to the death of the latter in 1819 no inconvenience was felt from this arrangement, by which one person was recognized as the titular chief and another was guaranteed as the actual ruler ; but Maharao Kishor Singh II (1819-28) attempted to secure the actual administration by force, and British troops had to be called in to support the regent's authority. In the battle that ensued at Mangrol (1821) the Maharao was defeated and fled to Nathdwara (in Udaipur), where in the following month he formally recognized the perpetual succession to the administration of Zalim Singh and his heirs, and was permitted to return to his capital. The old regent — 'the Nestor of Rajwara,' as Tod calls him — died in 1824 at the age of eighty-four, and was succeeded by his son, Madho Singh, who was notoriously unfit for the office, and who was in his turn followed by his son, Madan Singh. About the same time the Maharao died and his nephew, Ram Singh II (1828-66), ruled in his stead. Six years later, the disputes between him and his minister, Madan Singh, broke out afresh ; there was danger of a popular rising for the expulsion of the latter, and it was therefore resolved, with the consent of the chief of Kotah, to dismember the State and create the new principality of Jhalawar as a separate provision for the descendants of Zalim Singh.

This arrangement was carried out in 1838 and formed the basis of a fresh treaty with Kotah, by which the tribute was reduced by Rs. 80,000 and the Maharao agreed to maintain an auxiliary force at a cost of not more than 3 lakhs (reduced in 1844 to 2 lakhs). This force, known as the Kotah Contingent, mutinied in 1857; it is now represented by the 42nd (Deoli) Regiment. The State troops likewise mutinied and murdered the Political Agent (Major Burton) and his two sons, as well as the Agency Surgeon ; they also bombarded the Maharao in his palace. The chief was believed not to have attempted to assist the Political Agent,- and as a mark of the displeasure of Government his salute was reduced from 17 to 13 guns. Ram Singh, however, received in 1862 the usual sanad guaranteeing to him the right of adoption, and he died in 1866. For some years before his death the affairs of Kotah had been in an unsatisfactory condition ; the administration had been conducted by irresponsible and unprincipled ministers, and the State debts amounted at his death to 27 lakhs. He was succeeded by his son, Chhatarsal II (1866-89), to whom Govern- ment restored the full salute of 1 7 guns. A few years later, the affairs of State fell into greater confusion than before, and the debts increased to nearly 90 lakhs. At last, the Maharao, despairing of being able to effect any reform, requested the interference of the British Government, and intimated his willingness to receive any native minister nominated by it. Accordingly, in 1874, Nawab Sir Faiz All Khan of Pahasu was appointed to administer the State, subject to the advice and control of the Governor-General's Agent in Rajputana ; and on his retirement in 1876 the administration was placed in the hands of a British Poli- tical Agent assisted by a Council. The arrangement continued till ChhatarsaTs death in 1889, and during this period many reforms were introduced, and the debts had been paid off by 1885. He was suc- ceeded by his adopted son, Umed Singh II, who is the seventeenth and present chief of Kotah. His Highness is the second son of Maharaja Chaggan Singh of Kotra, an estate about 40 miles east of Kotah city. He succeeded to the gaddi in 1889, received partial ruling powers in 1892, and full powers in 1896. He was educated at the Mayo College at Ajmer (1890-92), was created a K. C.S.I, in 1900, and was appointed an honorary major in the 42nd (Deoli) Regiment in 1903. The most important event of his rule has been the restoration, on the deposition of the late chief of the Jhalawar State, of fifteen out of the seventeen districts which had been ceded in 1S38 to form that principality. Other events deserving of mention are the con- struction of the railway from the south-eastern border to the town of Baran ; the great famine of 1899-1900; the adoption of Imperial postal unity ; the conversion of the local rupees and the introduction of British currency as the sole legal tender in the State. The annual tribute payable to Government by the treaty of 181 7 was 2-9 lakhs. A remission of Rs. 25,000 was sanctioned in 1819, and, on the formation of the Jhalawar State in 1838, a further reduction of Rs. 80,000 was granted; but since 1899, when the fifteen Jhalawar districts were restored to Kotah, the tribute was raised by Rs. 50,000 and now stands at 2*3 lakhs, in addition to the annual contribution of 2 lakhs towards the cost of the Deoli Regiment.

Of interesting archaeological remains the oldest known is the cJiaorl at Mukandwara, belonging, it is believed, to the fifth century. The village of Kanswa, of which the old name was Kanvashram, or the her- mitage of the sage Kanva, about 4 miles south-east of Kotah city, possesses an inscription which is important as being the last trace of the Mauryas. It is dated in a. d. 740, and mentions two chiefs of this clan, Dhaval and Sivgan, the latter of whom built a temple to Mahadeo. Among other interesting places are the fort of Gagraun ; the ruins of the old town of Mau close by ; the village of Char Chaumu, about 20 miles to the north, with a very old temple to Mahadeo ; and lastly Ramgarh, 6 miles east of Mangrol, where there are several old Jain and Sivaite temples.

Population

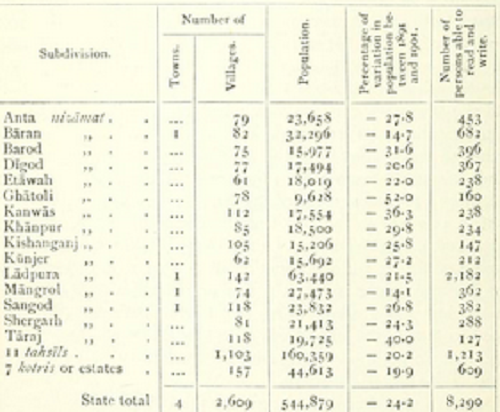

The number of towns and villages in the State is 2,613, and the population at each of the three enumerations was . (1881) 517,275, (1891) 526,267, and (1901) 544,879- The apparent increase of 3| per cent, in the last decade is due to the restoration of certain Jhalawar districts in 1899. In 1891 the territory now forming the Kotah State contained 718,771 inhabitants. Thus, during the subsequent ten years, there was a loss of 173,892 persons, or 24 per cent., which is ascribed to the great famine of 1899- 1900 and the severe epidemic of malarial fever that followed it. In 1 90 1 the State was divided into fifteen nizamats and ir fa/isl/s, besides jagtr estates, and contained 4 towns : namely, Kotah City (a munici- pality), Baran, Mangrol, and Sangod.

The following table gives the principal statistics of population in 1 90 1 : —

Of the total population, 487,657, or more than 89 per cent., are Hindus, the Vaishnava sect of Vallabhas being locally important ; 37)947> or nearly 7 per cent, Musalmans ; and 12,603, or more tnan 2 per cent., Animists. The language mainly spoken is Rajasthani, the dialects used being chiefly HaraotI, Malwi, and Dhundarl (or Jaipur!). Of castes and tribes the most numerous is the Chamars. They number 54,000, or nearly 10 per cent, of the population, and are by hereditary calling tanners and workers in leather, but the majority now live by general labour or by agriculture. Next come the Mlnas (47,000), a fine athletic race, formerly given to marauding but now settled down into good agriculturists. The Dhakars (39,000) are mostly cultivators ; the Brahmans (39,000) are employed in temples or the service of the State, and many hold land free of rent ; the Malis (36,000) are market-gardeners and cultivators ; the Gujars (35,000) are cattle-breeders and dealers, and also agriculturists. Among other castes may be mentioned the Mahajans (20,000), traders and money-lenders, and the Rajputs (15,000), the majority of whom belong to the Hara sept of the Chauhan clan. The Rajputs look upon any occupation save that of arms or government as derogatory to their dignity ; many of them are in the service of the State, chiefly in the army and police, or hold land on privileged tenures, but the majority are cultivators and, as such, lazy and indifferent. Taking the population as a whole, about 47 per cent, live solely by the land, and another 20 per cent, combine agriculture with their own particular trade or calling.

Of the 335 native Christians enumerated in 1901, all but 2 were returned as Presbyterians. The United Free Church of Scotland Mission has had a branch at the capital since 1899.

Agriculture

The country is fertile and well watered. The soils are divided locally into three classes : namely, kail (or sar-i-mal), a rich black loam containing much sand and decomposed vege- . table matter ; utar-mdl, a loam of a lighter colour but almost equally fertile ; and bar/, a poor, gravelly, and sandy soil, of a reddish colour, often mixed with kankar. On the first two classes, fine crops of wheat, gram, &c, are grown without irrigation. Agricultural statistics are available for about 4,778 square miles, or 84 per cent, of the total area of the State, comprising all the khalsa lands and detached revenue-free plots, and some of the jagir estates. After deducting 1,544 square miles occupied by forests, roads, rivers, villages, &c, or otherwise not available for cultivation, there remain 3,234 square miles, of which nearly 1,400, including about 40 square miles cropped more than once, are ordinarily cultivated each year, i.e. about 43 per cent, of the cultivable area. The net area cropped in 1903-4 was 1,315 square miles, and the areas under the principal crops were (in square miles) : 381, or nearly 29 per cent., under jozvdr; 359, or about 27 per cent., under wheat; 197, or 15 per cent., under gram ; 82 under linseed; 68 under til; 40 under both poppy and maize; t>2> under cotton ; and 20 under barley. There were also a few square miles under san (Indian hemp), indigo, bajra, tobacco, and rice.

The indigenous strain of cattle is of an inferior type, and all the best bullocks are imported from Malwa. There is a little horse and pony- breeding. Sheep and goats are reared in considerable numbers, but are of no distinctive class. Of the total area cultivated in 1903-4, 104 square miles, or between 7 and 8 per cent., were irrigated: namely, 87 from wells, 11 from canals, and about 6 from tanks and other sources. The wells are the mainstay of the State, and number over 24,000, more than half being of masonry. The water is for the most part lifted by means of leathern buckets drawn up with a rope and pulley by bullocks moving down an inclined plane ; but in a few places the renth or Persian wheel is used, and, in the case of shallow wells, the water is raised by a contrivance known as a dhenkd, which consists of a pole, supported by a prop, with a jar or bucket at one end and a heavy weight at the other. Of canals, the most important has been mentioned in connexion with the Parbati river. There are altogether about 350 tanks, of which 30 are useful for irrigation. The principal is that known as the Aklera Sagar, which has cost about Rs. 80,000; it has, when full, an area of about \\ square miles, and holds up 260 million cubic feet of water. Considerable attention is being paid to the subject of irrigation, and several pro- mising works are under construction : notably the Umed Sagar, in the Kishanganj district in the east, which is estimated to cost over 2 lakhs, and to have a capacity of more than 400 million cubic feet of water.

There are no real forests in Kotah, and valuable timber trees are scarce. The principal trees are teak, which, however, seldom attains any size, babul (Acacia arabica), bar (Fiats bengalensis), bel (Aegle Marmelos), dhak (Bit tea frondosa), dhonkra (Anogeissus pendttla), gular (Fiats glomerata), jamun (Eugenia Jambolana), kadamb (Anthocephalus Cadamba), mahua (Bassia latifolia), mm (Melia Azadirachta), plpal (Fiats re/igiosa), salar (Boswellia serrala), semal (Bombax mala* baricum), and lend/7 (Diospyros tomentosa). The forests have never been regularly surveyed, but their area (including several large game preserves) is estimated at about 1,400 square miles. There was no attempt at forest conservancy till about 1880, and it is only within recent years that any real progress has been made. Several blocks have been demarcated and entirely closed to cutting and grazing, and plantations and nurseries have been started. The receipts — derived from grazing fees and the sale of wood, grass, and minor produce such as gum, honey, and wax — have risen from Rs. 37,000 in 189 1-2 to over Rs. 69,000 in 1903-4, and the net revenue in the last year was Ks- 33, 3°°-

The mineral products are insignificant. Iron is found near Indar- garh in the north and Shahabad in the east ; the ore is rudely smelted, and the small quantity of metal obtained is used locally. Good building stone is found throughout the State.

Trade and communications

The most important indigenous industry is that of cotton-weaving. The muslins of Kotah city have a more than local reputation ; they are Both w hite and coloured, the colours being in some communications. cases P art i cu 'arly pleasing, and are occasionally orna- mented by the introduction of gold or silver threads while still on the loom. Cloths are printed and dyed at the capital and several other places. The tie and dye work (called chundri bandish) of Baran is very interesting, but the demand for it is annually diminishing, probably because of the increased import of cheap printed foreign cloths. Among other manufactures may be mentioned silver table- ornaments and rough country paper at the capital, embroidered elephant and horse-trappings at Shergarh, inlaid work on ivory, buffalo horn, or mother-of-pearl at Etawah, lacquered toys and other articles at Gianta and Indargarh, and pottery at the place last mentioned. There is a small cotton-ginning factory at Palaita about 25 miles east of Kotah city ; it is a private concern started in 1898, and when work- ing gives employment to about thirty persons.

The chief exports are cereals and pulses, opium, oilseeds, cotton, and hides ; while the chief imports are salt, English piece-goods, yarn, rice, sugar, gur (molasses), iron and other metals, dry fruits, leathern goods, and paper. The trade is mostly with Bombay, Calcutta, and Cawnpore, and the neighbouring States of Rajputana and Central India. The opium, which is claimed to be as good as, if not superior to, the Malwa product, is manufactured into two different shapes. That for the Chinese market, which is sent mostly to the Government depot at Baran and thence to Bombay, is prepared in balls, while that for home consumption or for other States in Rajputana — chiefly Blkaner, Jaisalmer, and Jodhpur — is made up into cakes. The chief centres of trade are Kotah city and Baran, and the principal trading castes are the Mahajans and Bohras.

The only railway in the State is the Blna-Baran branch of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, which was opened for traffic in May, 1899. The section within Kotah limits (about 29 miles) is the property of the Darbar, cost more than 17 lakhs, and has four stations. The net earnings of this section during the five years ending 1904 averaged Rs. 24,000 per annum, or a little less than \\ per cent, on the capital outlay. The actual figures for 1904 were : gross earnings, Rs. 52,000 ; expenses, Rs. 26,000; and net profits, Rs. 26,000, or about 1-55 per cent, on the capital outlay. An extension of this line from Baran to Marwar Junction on the Rajputana-Malwa Railway has been sur- veyed, and the greater part of the earthwork within Kotah limits was constructed by famine labour in 1899-1900. A line from Nagda (in Gwalior in the south) to Muttra has recently been sanctioned and work has commenced ; it is to run via the Mukandwara pass to Kotah city, and thence north-east through Bundi and past Indargarh.

The total length of metalled roads is 143 miles, and of unmetalled roads 410 miles ; they were all constructed and are maintained by the Public Works department of the State. The more important metalled roads lead from the capital to Baran, Bundi, and Jhalrapatan. Prior to 1899 the State had a postal service of its own, which cost about Rs. 5,000 annually ; but in that year the Darbar adopted Imperial postal unity, and there are now 32 British post offices, 2 of which (at Kotah and Baran) are also telegraph offices.

Famine

So far as records show, the famine of 1 899-1900 was the first that ever visited the State. When in former times famines were devastating the surrounding districts, Kotah remained free from severe distress, and was able to help her neighbours with grain and grass. In 1804 the regent (Zalim Singh) was able to fill the State coffers by selling grain at about 8 seers for the rupee, and Kotah is said to have supported the whole population of Rajwara as well as Holkar's army. In 1868, and again in 1877, the rains were late in coming, and the kharif crop was meagre ; but the spring harvest was up to the average, and, though prices ruled high for a time, there was, on the whole, little suffering. The famine of 1 899-1 900 was severe, and the entire State was affected. The rainfall in 1899 was but 15 ½ inches, of which more than 7 fell on one day (July 8), and after that date the rain practically ceased. The out-turn of the kharif was 18 per cent, of the normal, and rabi crops were sown only on irrigated land. The advent of the railway to Baran had created a greatly increased export trade, and the high prices prevailing in other parts of India tempted the dealers to get rid of their stores of grain in spite of the local demand. The difficulties of the situation were enhanced by an unprecedented wave of immigration from the western States of Rajputana, and from Mewar, Bundi, and Ajmer-Merwara. Thousands of needy foreigners poured into Kotah with vast herds of cattle, and by December, 1899, the grazing resources of the country had been exhausted. The Maharao was insistent from the first on a generous treatment of the sufferers, and by his personal example did not a little to mitigate distress. Poorhouses were opened at the capital in Septem- ber, 1899, and subsequently at other places, and relief works were started in October; other forms of relief were famine kitchens, the grant of doles of grain to the infirm and old and to parda-nashln women, advances to agriculturists, and the gift of clothes, bullocks, and seed-grain. More than six million units were relieved on works, and three millions gratuitously, at a cost of 7^ lakhs. The total expenditure, including advances to agriculturists, exceeded 9-5 lakhs, and over 15 lakhs of land revenue was suspended. The mortality among human beings was considerable, and, though the forests and grass-preserves were thrown open to free grazing, 25 per cent, of the live-stock are said 1" have perished.

Administration

The administration is carried on by His Highness the Maharao, assisted by a Diwan. Since 1901 the administrative divisions have Administration ^ een rern °delled, and there are now 19 niza?nats and 4 tahsil. Each of the former is under a nazim, and each of the latter under a fahsi/dtir, and these officers are assisted respectively by naib-nazims and naib-tahsildars. for the guidance of its judiciary the State has its own codes, framed in 1874 largely on the lines of the British Indian enactments, and amended from time to time by circulars issued by the Darbar. The lowest courts are those of the tahsilddrs (usually third-class magistrates) and nazims (generally second-class magistrates) ; they can also try civil suits not exceeding Rs. 300 in value. Appeals against their decrees in criminal cases lie to one of three divisional magistrates (faujddrs), who are further empowered to pass a sentence of two years' imprisonment and Rs. 500 fine. Similarly, appeals against the decisions of nazims, &c, in civil cases lie to one of two courts, which can also deal with original suits not exceeding Rs. 1,000 in value. Over the faujddrs and the two courts just mentioned is the Civil and Sessions Judge, who can try all suits of any description or value, and can pass a sentence of seven years' imprisonment and Rs. 1,000 fine. The highest court and final appellate authority is known as the Mahakma khds ; it is presided over by the Maharao, who alone can pass a death sentence.

The ordinary revenue in a normal year is about 31 lakhs, and the ordinary expenditure about 26 lakhs. The chief sources of revenue are : land about 24 lakhs, and customs about 4 lakhs. The chief items of expenditure are : army and police, 5 lakhs ; tribute to Govern- ment, including contribution towards the cost of the 42nd (Deoli) Regiment, 4-3 lakhs ; revenue and judicial staff (including Mahakma khds), 3-8 lakhs; public works department, 2-5 lakhs ; palace and privy- purse, 2-3 lakhs; charitable and religious grants and pensions, i-8 lakhs ; and kdrkhdnas (i.e. stables, elephants, camels, bullocks, &c), 1-2 lakhs. In the disastrous famine year of 1899- 1900 the receipts were about half the average, and the Darbar had to borrow from Government and private sources almost a year's revenue to enable it to carry on the administration and afford the necessary relief to its distressed population. The result is that the State now owes about 13 lakhs, though it has a large cash balance, besides investments.

Kotah had formerly a silver coinage of its own, minted at the capital and Gagraun (probably since the time of Shah Alam II), while in the restored districts the coins of the Jhalawar State were current. The rupees were in value generally equal, if not superior, to the similar coins of British India ; but in 1899, when large purchases of grain had to be made outside the State, the rate of exchange fell, and at one time both the Kotah and Jhalawar rupees were at a discount of 24 per cent. The Darbar thereupon resolved to abolish the local coins and intro- duce British currency as the sole legal tender in the State. This very desirable reform was, with the assistance of Government, carried out between March 1 and August 31, 1901, at the rate of 114 Kotah (or 118 Jhalawar) rupees for 100 British rupees.

The land tenures are the usual jagir, tnud.fi, and khdlsa, and it is estimated that the estates held on the first two tenures occupy about one- fourth of the area of the State. The jagirdars hold on a semi-feudal tenure, and are not dispossessed save for disloyalty or misconduct ; they have the power of alienating a portion of their estates as a provision for younger sons or other near relatives, and they may raise money by a mortgage, but it cannot be foreclosed. No succession or adoption can take place without the Maharao's consent, and in most cases a nazarana or fee on succession is levied. The majority of the jagirdars pay an annual tribute, and some of them have also to supply horsemen or foot-soldiers for the service of the State. Lands are granted on the nutafi tenure to individuals as a reward for service or in lieu of pay or in charity, and also to temples and religious institutions for their upkeep. They are usually revenue free. In the khalsa area the tenure of land was very widely changed early in the nineteenth century by the administrative measures of the regent, Zalim Singh. Before his time two-fifths of the produce belonged to the State, and the remainder to the cultivator after deduction of ^village expenses. Zalim Singh surveyed the lands and imposed a fixed money-rate per blgha, making the settlement with each cultivator, and giving the village officers only a percentage on collections. By rigorously exacting the revenue, he soon broke down all the hereditary tenures, and got almost the whole cultivated land under his direct proprietary management, using the cultivators as tenants-at-will or as farm-labourers. A very great area was thus turned into a vast government farm ; and while the proprietary status of the peasantry entirely disappeared, the country was brought under an extent of productive cultivation said to be with- out precedent, before or since, in Rajputana. At the present time the chief claims to be the absolute owner of the soil, and no cultivator has the right to transfer or alienate any of the lands he cultivates. So long, however, as the cultivator pays his revenue punctually he is left in undisturbed possession of his holding, and if he wishes to relinquish any portion thereof he can do so in accordance with the rules in force. In some of the ceded districts the manotidari system is in force, under which the manotidar or money-lender finances the cultivators, is re- sponsible for their payments, and collects what he can from them, while elsewhere the land revenue system is ryotivari.

The rates fixed by Zalim Singh remained more or less in force till about 1882-5 in the case of the restored tracts, and 1877-86 in the case of the rest of the territory, when fresh settlements were made, which are still in force. The rates per acre vary from 4^ annas to Rs. 5-8 for 'dry' land, and from Rs. 2-4 to Rs. 17-9 for irri- gated land. A revision of the settlement is now in progress, operations having been started at the end of 1904.

The Public Works department has been under the charge of a quali- fied European Engineer since 1878, and the total expenditure down to the end of 1905 amounts to about 80 lakhs. The principal works carried out comprise the metalled and most of the fair-weather roads, the masonry causeways over the Kali Sind and other rivers, the pontoon-bridge over the Chambal, the earthwork of the proposed Baran-Marwar Railway, several important irrigation tanks and canals, the Maharao's new palace (with electric light installation), the Victoria Hospital for women, numerous other hospitals and dispensaries, the Central jail, the public offices, resthouses, &c.

The military force which the Maharao may maintain is limited to 15,000 men, and the actual strength in 1905 was 7,913 of all ranks : namely, cavalry 910 (609 irregular), artillerymen 353, and infantry 6,650 (5,456 irregular). There are also 193 guns, of which 62 are said to be unserviceable. The force cost about 4-8 lakhs in 1904-5, and is largely employed on police duties or in garrisoning forts. There are no British cantonments in Kotah ; but under the treaty of 1838, as amended in 1844, the Darbar contributes 2 lakhs yearly towards the cost of the 42nd (Deoli) Regiment, of which His Highness has been an honorary major since January, 1903.

There are two main bodies of police : namely, one for the city (177 of all ranks) under the kotwal ; and the other for the districts, number- ing 5,260, and including 3,490 sepoys and sowars belonging to the army, and 1,668 chaukidars or village watchmen under a General Superintendent. The districts are divided into six separate charges, each under an Assistant Superintendent, and there are altogether 39 thanas or police stations and 516 outposts. Excluding the men be- longing to the army, and the chaukidars, who receive revenue-free lands for their services, the force costs about Rs. 45,000 a year.

Besides the Central jail at the capital, there are small lock-ups at the head-quarters of each district, in which persons under trial or those sentenced to short terms of imprisonment are confined. In regard to the literacy of its population, Kotah stands last but one among the twenty States and chiefships of Rajputana, with 1-5 per cent, of the population (2-9 males and o-i females) able to read and write. The first State school was started in 1867, when two teachers were appointed, one of Sanskrit and the other of Persian. In 1874 English and Hindi classes were added ; but this was the only educational insti- tution maintained by the Darbar up to 1881, when the daily average attendance was 186. In 1891 there were 19 State schools with a daily average attendance of 752, and by 1901 these figures had increased to 36 and 1,106 respectively. Similarly, the State expenditure on educa- tion rose from about Rs. 4,000 in 1880-r to nearly Rs. 9,000 in 1 890-1, and to Rs. 25,000 in 1900-1. Omitting indigenous and private schools not under the department, there were 41 educational institutions maintained by the Darbar in 1905, and the number on the rolls was 2,447 (including 115 girls). The daily average attendance in 1904-5 was 1,586 (75 being girls); and the total expenditure, including Rs. 5,000 on account of boys attending the Mayo College at Ajmer, was Rs. 33,000. Of these 41 schools, 39 are primary; and of the latter, 5 are for girls. The only notable institutions are the Maharao's high school and the nobles' school, which are noticed in the article on Kotah City. In spite of the fact that no fees are levied anywhere, and that everything in the shape of books, paper, pens, &c, is supplied free, the mass of the people are apathetic and do not care to have their children taught.

The State possesses 2 1 hospitals, including that attached to the jail, with accommodation for 216 in-patients. In 1904 the number of cases treated was 105,464 (1,808 being those of in-patients), and 3,765 opera- tions were performed. Vaccination appears to have been started about 1866-7 anc * is nowhere compulsory. In 1904-5 a staff of five men successfully vaccinated 16,351 persons, or 30 per 1,000 of the population. The total State expenditure in 1904-5 on medical institutions, including vaccination and a share of the pay of the Agency Surgeon and his establishment, was about Rs. 60,000.

[W. Stratton, Kotah and the Haras (Ajmer, 1899); P. A. Weir and J. Crofts, Medico-topographical Account of Kotah (1900); Kotah Ad- ministration Reports (annually from 1894-5).]

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.