Kotia, panchayat

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Claimed by both Andhra and Odisha

Kumuti Gamel of Neridiwalasa village has been expecting the rush of officials with health camps, financial packages and other schemes. It is, after all, election time, and such heightened activity by the administration is common across India.

But there is a difference: Neridiwalasa and 27 other villages under Kotia panchayat see the arrival of officials from both Odisha and Andhra Pradesh, because both states have laid claim to the area.

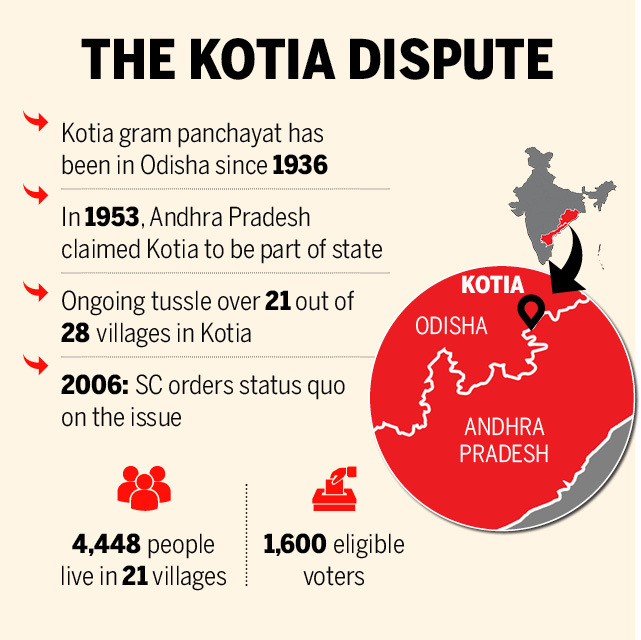

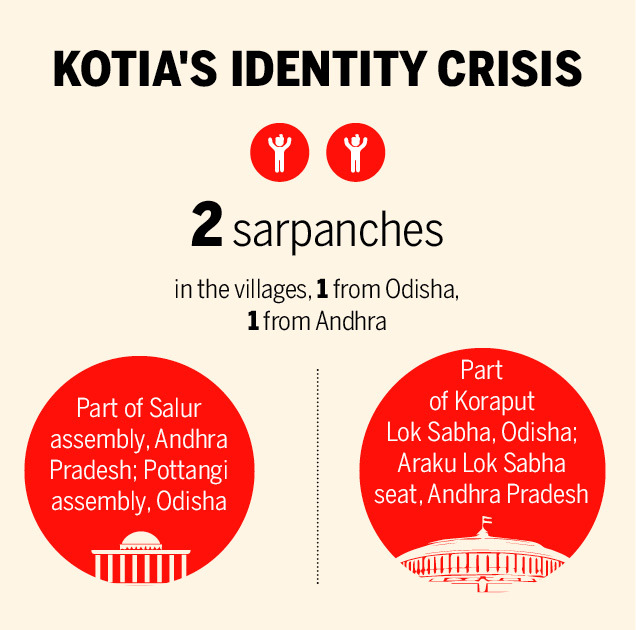

Kotia - which has officially been in Odisha since the state was formed in 1936 and was claimed by what was undivided Andhra Pradesh when that state was formed in 1953 - is part of the Pottangi assembly seat and the Koraput Lok Sabha seat in Odisha, but also in the Salur assembly and Araku Lok Sabha constituencies in Andhra. The status of Kotia is sub judice as both states went to court and the dispute has been before the Supreme Court since 1968.

THE KOTIA DISPUTE

Twenty one of Kotia's 28 villages have been at the centre of the tussle. The dispute escalated in January 2018 after the Andhra government launched Janmabhoomi programme there, and the collector of Vizianagaram district attended the event without, as Odisha claimed, intimating his counterpart in Koraput. This prompted the BJD government here to announce schemes for Kotia. Now, with polls in both states and national elections just months away, both governments have once again gone into overdrive.

On January 7, officials from Andhra visited Neridiwalasa and distributed blankets and diet supplements among children and pregnant women. They also conducted a free health camp there. The following day, Koraput collector K Sudarshan Chakravarthy visited Phagunasenari village for a programme to make people aware of the Odisha government's schemes. This, too, was followed by a free health camp. In the last week of December, Andhra officials had visited with Aadhaar cards and old-age pension papers.

Andhra's alleged intrusion last January had prompted Odisha to declare a special package of Rs 150 crore for the development of Kotia, which has predominantly tribal residents.

Andhra's alleged intrusion last January had prompted Odisha to declare a special package of Rs 150 crore for the development of Kotia, which has predominantly tribal residents.

It announced a 10-bed hospital, a high school, a police station, a bus service, electrification of villages and roads worth Rs 5 crore.

"The state government is developing infrastructure in Kotia. These projects are being regularly monitored and all social security programmes of the state are being implemented here," said Chakravarthy.

The residents are not complaining. "This (pre-election activity) is not new for us but this time, there is stiff competition between both states to win us over," said Kotia resident Suku Pangi.

Koraput district officials said that while the administration usually designated seven booths for the Kotia panchayat during the general election, the Andhra government designated three for the 21 disputed villages. With a population of 4,448, the villages have around 1,600 eligible voters.

During the 2014 general election, Kotia voted twice. On April 10, the residents voted to elect MP for Koraput Lok Sabha seat; on May 7, they voted to elect the legislator of the Araku Lok Sabha seat. In the event of a clash in election dates, the villagers say they will vote in the Odisha polls.

Elections

Voting in two states/ 2024

Nalla Babu & Umamaheswara Rao, April 10, 2024: The Times of India

Voters in Kotia along Andhra Pradesh and Odisha border have been caught in a decades-long territorial dispute between the two states. But they aren’t complaining. Call it a case of having the best of both worlds or having your cake and eating it too but Kotia voters say they enjoy a rare privilege — the right to cast votes in two states.

Over 2,500 electors of the 21 tribal villages hold voter IDs, ration cards, and even pension cards of both states as they fall under two Lok Sabha constituencies: Araku in Andhra and Koraput in Odisha. In 1968, Odisha moved SC laying claim to the villages. The court, however, ruled that interstate boundary issues fall outside its jurisdiction and can only be resolved by Parliament. Consequently, a permanent injunction was imposed, restraining either of the states from taking any action.

However, when asked about the double voting rights, Andhra’s CEO Mukesh Kumar Meena called it illegal. “One person can cast only one vote at one location. Enrolment in two states is illegal. One should cancel the registration in one state to enrol in another,” he said.

Nevertheless, the big question these electors face this time is which state they will vote in, as both Araku and Koraput go to polls on May 13. To get a feel of the geopolitical complexities and the voter pulse, TOI visited this cluster. Here’s the tug-of-war: Andhra claims the villages belong to its ParvathipuramManyam district, while Odisha asserts they lie in Koraput. Land surveys, records, and various forms of evidence fuel arguments from both sides vying for control. Development initiatives, political disputes, and resource allocation further complicate matters.

In the run-up to elections, debates here centre around the contrasting approaches of the two states — Odisha’s infrastructure push versus Andhra’s welfare programmes. Odisha has made significant inroads, cementing its presence with concrete roads connecting villages to Kotia, the main panchayat. It has also established schools, a primary health centre, and an Indian Reserve Battalion outpost. Andhra, meanwhile, is focusing on financial aid through welfare schemes. This becomes evident while traversing from Salur in Andhra towards Kotia, as one nears the Odisha border.

While voters residing downhill seem to identify more closely with Andhra, those uphill may favour Odisha. But, generally, villagers, who eke out a living cultivating millets and some paddy on the rugged slopes of the Eastern Ghats, feel they hold the upper hand as dual identity cards grant them access to benefits of both the states.

For instance, Chodipalli Latchayya, a resident of Dhulibhadra hamlet in Salur mandal, Andhra, possesses a ration card under this identity. He also doubles up as Latchayya Pangi on another ration card in Odisha’s Pottangi block, Koraput. Similarly, Gemele Kati, who enjoys “voting rights” in both the states, has an Aadhaar card issued on an Andhra address, and is seeking a pension based on that.

Villages too have dual official names. “Ganjaeipadar” in Odisha becomes “Ganjaibhadra” in Andhra, influenced by Telugu. Similarly, “Nerallavalasa” in Andhra becomes “Naradbalsa” in Odisha, and “Pattuchenneru” becomes “Phatuseneri”.

When asked where they would vote, residents of Nerallavalasa and Thadivalsa — two of the 21 disputed villages — picked Andhra’s booth as the state offers more welfare schemes. Andhra provides a monthly welfare pension of Rs 3,000 compared to Odisha’s Rs 500. Andhra’s incentives, ranging from Rs 50,000 to Rs 1 lakh per family per year, are a big draw. In the Kotia cluster, consisting of tribals from Konda Dora, Mooka Dora, Gadaba, and Jatapu communities, some communicate in Telugu and Odia, but most speak the ‘Kui’ dialect.

Vanthala Sana, 60, from Nerellavalasa village under Sarika panchayat, said the dispute is only between the states, not people. “We receive more benefits from Andhra; I will vote at an Andhra booth,” she added. Abhi Gemel, who too receives benefits from both the states, said he would support Odisha as their culture is closer to that of the tribals of Koraput. However, the benefits have not translated into uplift. Most villagers are illiterate or dropouts, which is reflected in the low number of residents securing govt jobs in either state.

Tadangi Phulma from Yeguva Sembi (Upper Sembi) said, “I don’t know the names of the CMs.

I will walk to whichever booth is closer.

I don’t know who I will vote for; we will decide on voting day.” In 2019, when polling dates clashed (April 11), the few who managed to vote in both the states got inked on the left hand in Odisha and right hand in Andhra.

“Since they belong to both the states, they have the right to vote in both. We will see what happens this time,” said Ajay Ram Tarai, section officer, Panchayat Raj department, Pottangi block, Koraput.

But Meena maintained, “We will soon look into issue. They cannot vote in two states. Aadhaar seeding will solve the problem.”

Kotia police (Andhra) inspector, K Narayana Rao, said there is no law and order situation despite the border dispute. In 2021, however, the villages witnessed tension as political leaders and police personnel from Odisha prevented villagers from voting in Andhra’s local elections.